“We came for a day trip and ended up at Inkwell Beach,” Mekuria said when we sat down in the Oak Bluffs cottage she purchased five years ago. “I had no idea there were black people here. It was wonderful, and very welcoming.”

A decade after that initial visit, Mekuria returned to the Vineyard, and again she was struck by the vibrancy and depth of black community and culture on the Island. “I’ve always been intrigued by the fact that there were African Americans who had homes here, on a resort island.” By that point in her career she had traveled extensively, whether as a producer on projects for WGBH or on vacation with her family. “I went to some resorts here and there and it was always white. I never felt comfortable. For me, this was so unreal and surprising, and exciting.”

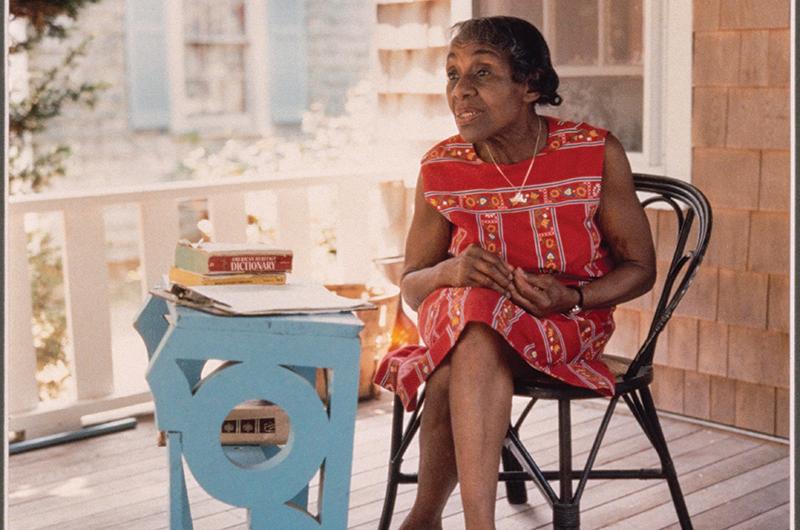

Surprise and excitement provoked deeper study of the history of African Americans on the Island, and eventually evolved into the thirty-minute documentary Our Place in the Sun, which was broadcast on WGBH in 1988 and earned Mekuria an Emmy nomination. While conducting research for Our Place in the Sun, she met Dorothy West, the Harlem Renaissance author and seasonal Vineyard resident. “It was a part of African American history I didn’t know much about,” Mekuria said of the Harlem Renaissance. In 1991 As I Remember It: A Portrait of Dorothy West, which she also filmed on the Island, premiered on WGBH and earned her another Emmy nomination.

In celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of her first film, the Martha’s Vineyard Museum will host a screening and panel discussion of Our Place in the Sun on August 4 at the Tabernacle in Oak Bluffs. A screening of As I Remember It will take place on August 23 at Union Chapel, also in Oak Bluffs. It will be followed by a question and answer session.

For Mekuria, who recently retired from her position as a professor in the art department at Wellesley College and now considers Oak Bluffs her primary residence, the retrospective screenings feel a bit like a coming out party. Though she has visited for decades and made meaningful connections in the artistic community, it has only been in recent years that she’s started to think of the Island as her personal and professional home.

Home is an important and recurring theme in Mekuria’s work. With the success of her first, Island-based films under her belt, she went on to delve deeper into her own personal history, with roots literally a world away from Oak Bluffs in the holy city of Axum, Ethiopia. There her father was head of the Ethiopian Orthodox church and mayor of the city, but Mekuria, who has always had an independent streak, left her parents and eight younger siblings to attend an all-girls boarding school in the capital, Addis Ababa. While in the capital she often snuck off to see films at a nearby theater, but “there were no men or women making films in Ethiopia,” she remembered. “It was not in my vocabulary.”

Instead, she enrolled in a city university, where she opted to study engineering. At the age of nineteen an international scholarship program brought her to Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, where she eventually transitioned to the study of political science and journalism. The year was 1967. Not only was she forced to adapt to a new country, far from a single familiar face, but with the American civil rights movement reaching a fever pitch, she was thrust into a heated political and cultural debate about which she understood very little.

“They were lovely,” Mekuria said of the host family she lived with at first, though she allows that she was oblivious to many of the racial undertones that were likely present in her early encounters as a black student in a predominately white community during increasingly tumultuous times. “They lived in White Bear Lake,” she added with a smile. “Whenever we went out to a restaurant they used to summon the manager and introduce me as their guest from Africa.

I thought it was celebrity status.”

As tensions grew on campus, Mekuria became more involved in student groups and organizations. While visiting a friend at Howard University in Washington, D.C., she was quarantined on campus after Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. “That was how I opened my eyes to what race meant here,” Mekuria said of her beginnings as an activist. “After that, I was in it.” She joined a committee of students, faculty, and administration at Macalester working to admit more African American students and hire more black professors. “They decided they would recruit one hundred African American students and give them full scholarships,” Mekuria said. “That was a great victory.”

As a visiting African student she had a unique perspective to offer the movement and was received warmly. “Being dark skinned, it wasn’t difficult for African Americans to embrace me,” she remembered. “And it was a time that they were being woken up to being Africans. So in a way it was a huge advantage. They thought I knew a lot.”

Despite her activism and a degree in political science, like many graduates Mekuria left college feeling confused about her future. She was dividing her time between Oakland, California, where she studied educational media and interned as a television producer, and Ethiopia, where she was following the burgeoning student movement. Then in 1977, a few years after the deposing of Emperor Haile Selassie and the violent political tumult that followed, her younger brother Selomon, who was a part of the movement, disappeared. Mekuria returned home to be with her family and friends and to look for him.

“It was another very confusing and complicated time. I tried to do some inquiries about my brother and I was stonewalled everywhere,” she remembered. After her return to the United States in 1979 and the success of her two Oak Bluffs films, this experience would serve as the foundation for what is perhaps her most personal documentary, Deluge, the wrenching story of her brother and a best friend, both casualties of the brutal post-revolutionary military regime. Another film, Sidet, profiles three Ethiopian refugee women in the Sudan.

Mekuria’s newest passion and the subject of her latest film is a small intentional community in rural Ethiopia called Awra Amba. Mekuria discovered the five-hundred-person community, which is devoted to the practices of gender inclusion, self-reliance, and environmental consciousness, after meeting its founder during her travels in the country. Last summer, with the help of nine Vineyard friends, she organized a fundraiser at the Martha’s Vineyard Hebrew Center featuring Ethiopian food and music. The event was well attended and raised about $70,000, which will allow the community to install a well and create its own sustainable water system.

“People are really generous here,” Mekuria said, noting that though Awra Amba is a tiny communal village many thousands of miles away, it upholds values important to many Vineyard residents. “It fits in with many people’s ideal way of life: sustainable living, alternative energy, water rights. In this political climate, people are struggling to bring these ideals together.”

Mekuria’s warmth and skill as storyteller were also key to the success of the event, said friend Cindy Kane. “Salem is like a low-burning flame. Her films are quietly empathic, and they creep up on you with their power and revelations. I think that in the current political situation people value modesty and getting things done without boasting about it. And that is Salem.”

Modesty and, Mekuria might add, an abiding sense of duty to those who have struggled in the past, both here and around the world. It was this sense of duty and the desire to contribute that shaped Mekuria’s interest in the Island and the prominent black figures and families profiled in her earliest films.

“My privileges being here were a result of their struggles,” Mekuria said. “I didn’t do anything to deserve all of the benefits as a black person here. I learned on their backs. I felt a responsibility to give back something, a very small thing, and to honor that gift.”