On a June day in 1957, children at the West Tisbury School were outside getting ready to enjoy their lunches. But at the stroke of noon they found themselves staring up at a helicopter sweeping low over the schoolyard and spraying chemicals on everything under its path, including them. According to a brief account in the Vineyard Gazette, some were unfortunate enough to have already opened their lunchboxes, and teachers advised them not to eat the contaminated food. The spraying was likely part of a regional effort to control gypsy moths, which had plagued the Island for decades. Or it might have been aimed at mosquitoes, cankerworms, or elm beetles, all of which found themselves in the crosshairs of rigorous Island pest control efforts in the twentieth century. Almost certainly, the substance raining down on the children contained the infamous insecticide known as DDT.

It is hard to imagine that such an event could happen today. But the truth is that many Islanders are equally skeptical of modern pesticides, including herbicides and insecticides widely used in their own neighborhoods. Unlike the previous generation’s encounters, however, little if any of the spraying today is initiated by town governments or the state. Instead, it’s mostly the residents themselves, or landscapers, who are left holding the nozzle.

Much of the current controversy centers on glyphosate, the most widely used herbicide in the world, whose safety even forty-eight years after its invention in 1970 remains shrouded in uncertainty. In 2015 the International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the World Health Organization, classified it as a probable carcinogen, contradicting several agencies that had previously declared it unlikely to cause cancer in humans. And a number of studies have suggested it may be toxic to earthworms, amphibians, and other organisms.

In response to Eversource Energy’s use of glyphosate and other chemicals to control vegetation under its power lines, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission and the town of Tisbury have recently explored options to limit the use of herbicides on the Island. And a drawn-out battle over the use of glyphosate to kill the invasive wetland reed phragmites resulted in a special act of legislature four years ago banning its use around Squibnocket Pond. Eversource has no plans to spray this year, but efforts to prevent the utility, or anyone else, from future use of the herbicide have so far failed.

What comes next is unclear. But if the previous century’s love-hate relationship with DDT is any guide, the debate is far from over.

Smith was elated by the results of the first aerial spraying in 1946, which covered two hundred acres with DDT and the remaining roads and residential areas with arsenate of lead. “Within an hour after the DDT was sprayed, caterpillars were observed dropping from the trees,” he wrote that year. Tisbury, West Tisbury, and Oak Bluffs teamed up the following spring to spray thousands of acres with the miraculous new substance, leading Smith to declare the gypsy moth thoroughly defeated in his town. He noted that a recent increase in moth parasites had likely contributed to the demise as well. “But there is no question that DDT finished the job.”

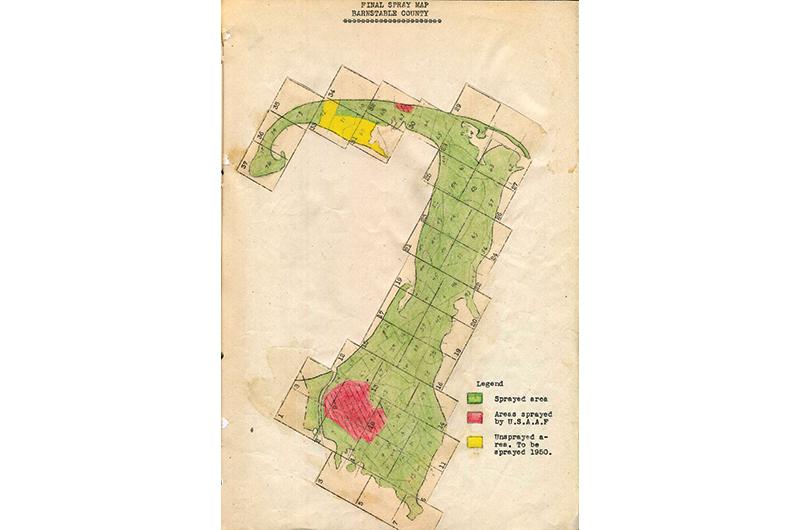

The aerial campaigns continued every year and expanded to combat new pests as well. When Dutch elm disease arrived on the Cape in the early 1950s, Island towns sprayed a mixture of DDT and malathion (another broad-spectrum insecticide, highly toxic to bees and some aquatic life) on roadside trees to kill elm beetles. Later they switched from DDT to Sevin, whose active ingredient, carbaryl, has been banned in several countries but not the United States. By that time a countywide mosquito control program had also evolved to rely largely on DDT, although some towns later resumed the older method of digging channels to drain the pools where salt marsh mosquitoes bred. And in 1956 Tisbury, West Tisbury, and Chilmark collaborated with the state Department of Natural Resources for Project Cankerworm, spraying at least 17,000 acres in those towns, taking a heavy toll on cankerworms and just about every other insect in the way. By the 1960s DDT had become the chemical of choice among several Island towns, not to mention an untold number of homeowners and farmers.

Not everyone was as sanguine as the moth agents and other officials. Years before Rachel Carson sounded the alarm over the dangers of DDT in her 1962 classic Silent Spring, many Vineyarders were pushing back against its use in their towns. No one knew for sure how it was affecting human health and the environment, but as early as the 1940s Islanders were registering complaints about the planes, helicopters, and trucks that would spray the substance every year, often leaving spots on their own vehicles. A majority of Edgartown farmers in 1949 called the safety of DDT “highly debatable” and petitioned the town not to spray it on their land.

By the late 1950s the Gazette had launched a crusade against “indiscriminate spraying” on the Island, showcasing the appeals of wildlife experts and frustrated residents and railing against the authorities that allowed the practice to continue. “Surely a few mosquitoes to keep the summer people slapping their suntan are not too high a price to pay for retention of living swamps, water table, stream and pond fish, an outdoors safe for all,” one resident wrote in a 1960 letter to the editor. In 1963 an entire neighborhood in Edgartown petitioned the town not to spray their properties with any type of insecticide.

But the opposition was far from universal, perhaps especially when it came to freshwater mosquitoes, which by the 1930s were known to carry encephalitis. Rebecca Gilbert of Native Earth Teaching Farm in Chilmark remembers how her grandmother, Cecil Gilbert, once stood in the middle of North Road with her arms outstretched to stop the mosquito truck from spraying DDT on her land. “The way the story goes is that my grandmother received several death threats,” Gilbert said. “Someone said, ‘If anybody’s child gets sick, we are going to come and burn down your barn – to start with.’”

Gus Ben David, an Island naturalist who grew up catching toads, crabs, and turtles around his home in Oak Bluffs, remembers riding his bike to the former Trade Wind Airport to watch the DDT helicopter take off with its payload. “It was one of those ones with a big glass bubble and the great big arms out on the side – pipes where the spray things were,” he said. He would watch it buzz Island marshes, leaving behind a film of deadly chemicals. “We thought they were just killing mosquitoes,” he said. “Well, it turns out they were killing a whole bunch of other things, and we didn’t know how these chemicals got into the food chain and how they compounded and built up.”

As it happened, DDT presented a case study in the complexity of cause and effect in nature and helped catapult ecology into the popular realm. It took decades for scientists to figure out that DDT accumulates in the bodies of animals, with the top predators in a food chain getting the highest dose since they essentially eat everything else. One consequence of DDT in the wild was that the eggshells of raptors became so thin they would break under the weight of the incubating parents or lose water through osmosis. As people everywhere continued to blithely apply the pesticide, ornithologists around the country scrambled to understand the resulting declines. The canary in the coal mine, so to speak, was no canary at all but a now-familiar Island visitor: the osprey. Because ospreys nest in conspicuous places – atop telephone poles or solitary dead trees – their decline drew more attention than that of peregrine falcons, for example, which tended to nest in remote cliffs and other hideaways.

When ornithologist Rob Bierregaard began monitoring Vineyard ospreys in 1971, there were only two breeding pairs on the Island. Surprisingly, though, fragile eggs weren’t the problem: the two pairs reared twenty-three young in the early 1970s, far more than even the largest osprey populations in the rest of the Northeast. But hardly any of the birds survived to adulthood.

“There were two mysteries,” recalled Bierregaard, who recently co-authored a paper with Ben David and others on the osprey’s dramatic recovery in the region. “One was, why were these birds doing so well when the ospreys in the rest of New England were doing terribly? And the other question was, why aren’t there more? If they are doing that well on Martha’s Vineyard, there should be more than just two pairs.”

Despite the regular use of DDT in Island towns, he said, it was only a fraction of the amount dropped on the mainland. Plymouth County alone sprayed more than 525,000 acres between 1948 and 1956, and nearly every square acre of the Cape was doused between 1949 and 1950. The spraying here also mostly avoided the Island marshlands, which supported the fish that in turn fed the ospreys. Bierregaard said the aerial spraying that did occur on the Vineyard was minor enough to allow the ospreys that reached adulthood to thrive.

It was Ben David, then director of the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown, who solved the second mystery. Working with Bierregaard in the 1970s, he discovered that Vineyard ospreys were indeed building nests, but often atop telephone poles, and the power company at the time would immediately knock them down to prevent outages. In addition, much of the Vineyard had long been cleared of dead trees where ospreys like to nest.

Rather than DDT, the greatest danger to Vineyard ospreys appeared to be Cape and Vineyard Electric. With Ben David on the case, however, the succeeding utility companies over the years – including Eversource Energy (formerly NStar) – have assumed a key role in reviving the Vineyard’s osprey population. The nests still had to be knocked down. (“Every year I’ve had them blow transformers up, start fires, it’s incredible,” Ben David said.) But now line workers assist in erecting poles nearby on which the ospreys can nest instead. The agreement kept the birds from coming back to the same telephone poles again, and launched a restoration program that has gained national recognition. Osprey numbers grew exponentially through the 1980s, with a record ninety breeding pairs as of last year. “Everybody loves them, everybody wants them,” said Ben David, who recently set up his 149th pole on the Island.

As early as 1957, the U.S. Department of Agriculture began phasing out certain uses of DDT in light of the potential risks to human health and the environment. Massachusetts finally banned the chemical in 1969, and a federal ban followed in 1972. But it had taken the groundbreaking journalism of Carson and decades of public opposition, culminating in a series of federal committees and reports in the 1960s, to turn the tide. Within a few years of the federal ban, concentrations of DDT in the environment dropped and the affected wildlife began to rebound.

On the Island, public controversy surrounding Eversource’s weed management approach flared last year, when it announced plans to resume spraying after a four-year moratorium, itself prompted by public concern. Several towns on the Cape, along with Vineyard Haven resident Marjorie Lau, quickly filed appeals to stop the work from going forward. None was successful, however, with the state Division of Administrative Law and Appeals citing, among other things, a lack of evidence showing that any harm has resulted from the spraying.

“In the big picture, the state is not listening to the towns,” said Laura Kelley, president of the advocacy group Protect Our Cape Cod Aquifer, which has been fighting for years to get Eversource to abandon chemicals in favor of mowing and trimming. She assisted roughly a dozen boards of selectmen in commenting on Eversource’s Yearly Operational Plan in 2017, but said the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, which approves the plans, only recognized one of them since they shared the same language. Of at least 1,000 comments from the public, only a small fraction were deemed “legitimate” and not simply based on feelings, she said. (The state Pesticide Advisory Board, which last year took no action on public requests to extend the four-year moratorium, did not respond to a list of questions for this article. An Eversource spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.)

“The state says, ‘Show us harm and we will change the regulations,’” said Kelley, although she noted that pesticides in the environment are nearly impossible to trace back to their source. And the widespread use of glyphosate by landowners and others makes it even harder to point a finger at any one user. Also, as DDT showed, it’s not always easy to connect the dots between massive amounts of chemicals and long-term consequences for the environment. Kelley has recently focused her efforts on a state law that prevents the use of chemicals within fifty feet of a private well, arguing that it should apply to vertical as well as horizontal distances. This could effectively reduce the spraying on most of the Cape and Vineyard, where the aquifer is close to the surface.

Kelley hopes that convincing Eversource to stop using herbicides will lay the groundwork for landscapers and others to follow suit. But in a report to the Cape Cod Commission in 2014, the Horsley Witten Group, an environmental science and engineering firm based in Sandwich, found that Eversource applied just 1.1 percent of all pesticides on the Cape, with private homeowners accounting for well more than two-thirds of the total 1.3 million pounds, including about 375,800 pounds applied by landscaping professionals. Another 43,200 pounds was used in agriculture. Similar figures for the Vineyard have not been collected, but extrapolating from the Cape study one could roughly estimate annual usage of 300,000 pounds on the Island, which covers just under a quarter as much area as the Cape and has about the same proportion of developed residential land.

“Eversource is a great way to make people aware of the situation,” said Ben Robinson, a member of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, a planning organization. “But we are doing it really to ourselves.” And despite the appearance of a David-and-Goliath battle, it’s generally the Goliaths that must follow legal guidelines and become certified to apply pesticides. “When you look at Eversource, whether they are following guidelines or not, they are going through that kind of process,” he said. “But homeowners don’t have to, and you can order this stuff on Amazon.”

Robinson believes an Islandwide ban on glyphosate would gain broad support, even though it would most likely require an act of legislature, since herbicides are regulated by the state, not towns. Meanwhile, many organizations have taken matters into their own hands. Polly Hill Arboretum in West Tisbury, for example, aims for an entirely natural approach to pest management on its seventy-two acres, including the promotion of biodiverse landscapes where pests have a harder time taking hold. But that wasn’t always the case. When Tim Boland, now the executive director, arrived as curator in 2002, he discovered a war chest of synthetic pesticides left over from the last century: DDT, malathion, carbaryl, and others. The arsenal was carefully disposed of during a hazardous waste collection day at the West Tisbury Transfer Station.

But while DDT was a wake-up call to environmentalists, so was it a lesson to chemical manufacturers whose own efforts to influence public opinion have become more sophisticated over the years. Boland sees the same type of promotion that pushed pesticides in the 1950s at work today. “There has obviously been what I believe to be a suppression of information by the companies that produce these chemicals,” he said.

As a young nursery man in Michigan, Boland himself spread thousands of gallons of glyphosate to control weeds. But he said people’s understanding of the chemical has changed since then. He also supports an Islandwide ban on glyphosate, but at the same time tries to remind people that weeds can simply be mowed, cut, or torched. “This sounds terrible,” he said, “but we should look toward the citizenry and say, ‘Hey, why don’t we try to find a budget for these things so we can not have to spray?’”

Still, many would argue that pesticides have their place, including on the Vineyard, where invasive plants have long rankled property owners and conservationists. Seth Wilkinson of Wilkinson Ecological Design, an ecological restoration firm on the Cape, noted that most scientific data relating to glyphosate are based on agricultural use, which involves spraying vast areas of cropland every year. “Invasive plant management is almost the other end of the extreme, where you are doing extremely targeted applications on a relatively limited time frame – usually three years or less,” he said. His firm occasionally uses glyphosate and triclopyr, an herbicide used on woody and herbaceous plants, but he argues those are often the most environmentally sound options when it comes to removing invasive species whose roots may extend ten feet or more underground. By targeting specific plants and applying small amounts of herbicide by hand, he said, the environmental benefits clearly outweigh the costs.

Eversource uses a combination of backpack sprayers and hand pumps under its power lines, which it says helps keep the chemical on the plants and off the ground. The company asserts this approach means less herbicide use over time, since it allows native, low-growing plants to take over. Glyphosate is generally thought to break down before it can reach groundwater, although no official studies on the Cape and Islands have been conducted.

Wilkinson, however, pointed out that even backpack sprayers can be used for broad-scale application. “It really depends on what is in the backpack and how the backpack is modified,” he said, adding that by definition what utilities are doing in their rights of way “is non-selective because they want to treat all the woody plants, and these areas are generally heavily colonized by woody species.”

He noted that a single test for pesticide applicators is meant to cover everything from weeds to mammals. “Licensing someone to apply pesticides does not make them a great or even knowledgeable applicator,” he said. “We’ve found that there is tremendous in-house training that’s needed even though someone may be licensed to do the work.”

DDT would have had no measurable effect beyond a year or two after application, in part because insects breed so quickly and abundantly that many develop resistance to the chemicals. And indeed, governments and farmers did find themselves doling out ever greater quantities of DDT to get the same results, a phenomenon echoed today by the worldwide explosion of glyphosate-resistant weeds.

In some cases, Elkinton said, even the perceived threats posed by an insect or plant are a matter of perspective. Gypsy moths and other defoliating insects, for example, have little long-term effect on Island forests, which are not harvested in any major way for wood, and generally will recover from the loss of trees. “The ecosystem impact of any of these defoliators is minimal,” he said. But he also noted the obvious danger to shade trees in yards and public spaces. “The real impact is on human beings.”

In the case of glyphosate and other chemicals widely used on the Island, the benefits are easy to identify: more reliable electricity, greener lawns, fewer invasive plants, blemish-free foods, lower maintenance bills.

It’s the costs of decades and decades of spraying – to human health and the environment – that are still unknown. Several studies have linked pesticides, including glyphosate, to a drastic decline in bees worldwide, for example, although habitat loss, parasites, and climate change also appear to play a role. “That’s another one of those topics where it’s very hard to point a finger unambiguously,” said Paul Goldstein, an Island resident and entomologist who specializes in moths and butterflies at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In the case of insect species in general, he said, “Usually what happens is, by the time we notice something is wrong, it’s too late.”

Goldstein makes an urgent case for conserving insect habitats everywhere – and soon. With its coastal sandplain and other rare habitats, Martha’s Vineyard in particular enjoys the highest concentration of threatened invertebrates in the Northeast. But a worldwide decline in flying insects – attributed to some combination of pesticides, parasitoids, and metal halide lamps – casts doubt on the fate of insect species on and off the Island. Peer-reviewed studies in Germany place the global figure as high as 75 percent. According to Goldstein, the Island already has seen a decline in some butterflies and the vast array of bees. There are also anecdotal reports of declines in some large moths in West Tisbury since the 1980s, and there is evidence that the Island may be becoming a final refuge for other species. Imperial moths blinked out on the mainland in the 1990s (some experts partly blame the pesticides used to control gypsy moths), leaving the Vineyard with the only remaining population in the Northeast.

In other words, while the dwindling birds of prey became a potent symbol of the perils of DDT fifty years ago, concerned citizens today might claim their own poster children in the fight against harmful pesticides, although it might seem a bit ironic compared to the 1950s: insects. And we have barely scratched the surface of what insects might tell us about the natural world.

“We have an unexplored biological, biochemical, ecological territory out there that’s disappearing faster than we can understand it,” said Goldstein. “It’s worth more than we can possibly imagine, and possibly more than we’ll ever know.”