A few years later Professor Benjamin Silliman of Yale was at work at Gay Head extracting “petrifactions” from the Cliffs when he made an unusual find. “The vertebra of a Lizard was shown me as large in circumference as an ordinary plate, or the inner edge of my hat brim,” wrote the author Samuel Devens in his 1838 travelogue, “Sketches of Martha’s Vineyard.” “This lizard, so thought Professor Silliman, must have been one hundred feet long and belonging to a species now extinct.”

More monster sightings followed. In 1859, two frightened Gay Head fishermen claimed that they had been chased by “the veritable sea serpent” off Noman’s Land. In 1897, the officers of the steamer Gloucester saw a white serpent off Gay Head, forty or fifty feet long, resembling a gigantic eel.

Nor did the fun stop with the arrival of the twentieth century. In 1927 the Vineyard Gazette reported that Joseph Bettencourt, an Edgartown scalloper, hauled aboard a huge skull while dragging in Katama Bay. It had a “decided reptilian cast” and likely belonged to some “prehistoric monster.” Another account added “the skull was three feet across, had no teeth but had cavities for the eyes and ears.” Bettencourt gave the skull to fish buyer Charles Johnson of Edgartown, who sent photographs of it – or by some reports, the skull itself – to Yale for identification. “Ancient tales of huge sea serpents have been aroused by the find, and it may be that the bony structure is the last remains of some dinosaur of the Mesozoic period,” concluded the Gazette. (Dr. Chris Norris, the current collections manager of Yale’s Peabody Museum, reports that “while the description sounds like a whale skull, I can’t find any evidence that it’s in the collection here.”)

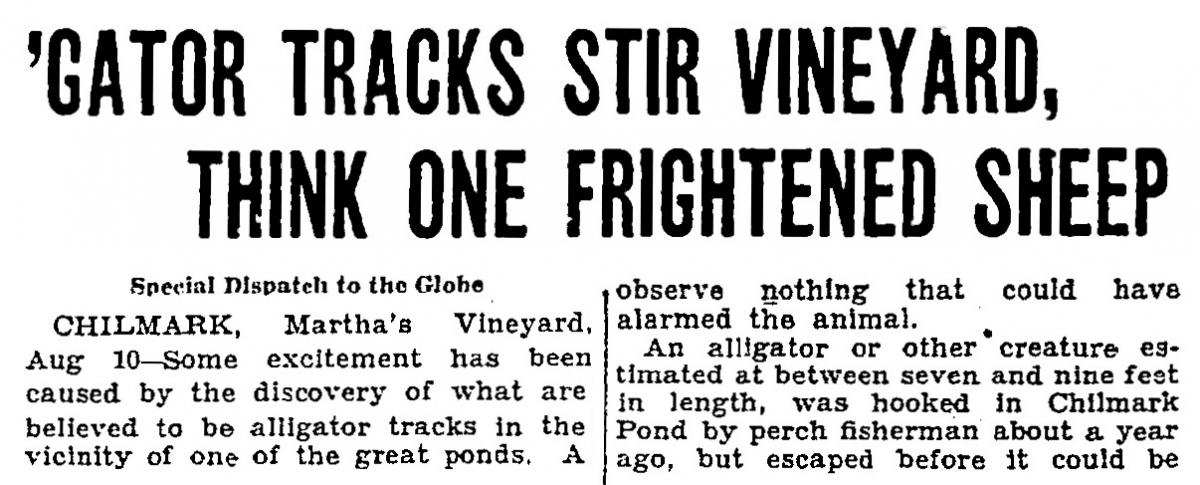

That same year a Boston Globe article titled “’Gator Tracks Stir Vineyard” reported the sighting of alligator tracks near one of the great ponds in Chilmark (and a nearby farmer’s story of his badly frightened sheep). “An alligator or other creature estimated at between seven and nine feet in length was hooked in Chilmark Pond by perch fishermen about a year ago, but it escaped before it could be raised to the surface,” the article read. “Alligators supposed to have escaped from vessels have been found on the Vineyard beaches at different times, but it has never before been believed that the creatures could survive the Winter in this latitude.” Vineyard Gazette publisher Henry Beetle Hough mentioned an

undated but similar story in his book, Once More the Thunderer: “An observer with binoculars told of watching an alligator emerge from Chilmark Pond.”

In 1930 a Captain Colwell and his mate reported a bright yellow serpent off the Vineyard’s coast longer than their fifty-two-foot trawler, with four frog-like legs and a head like a long-eared cow. Reporter Joseph Chase Allen, meanwhile, wrote in a 1952 column for the Gazette that “it was one of the Norton family who once told us about the sea-lizard with six sets of legs, that landed at Pocha and walked clean across Chappaquiddick, killing and swallowing a calf on the way!”

Most of the serpent accounts can be explained away as unusual whale or shark specimens. Or wandering oarfish: two years ago a seven-foot oarfish, normally a deep-water fish that can grow to fifty feet or more, beached itself temporarily on Nantucket. A 1937 case of sea serpents spotted off Nantucket was part of a hoax perpetrated by a pair of con artists. Professor Silliman’s vertebra, meanwhile, was likely from an extinct whale-like species known as the Basilosaurus, whose teeth have since been found in the fossil-rich Cliffs at Aquinnah. And Allen was known for his playful exaggeration and his celebration of colorful folk tales.

But one story is true: for many years an alligator named Boswell, or Bozzy, lived in the warm interior of the Barnacle Club headquarters in Vineyard Haven, where he was doted on by old salts and kept company by a snapping turtle named Pete, two turtles named Pro and Con, and eventually by Louie Loggerhead, a “vicious snapping turtle.”

Nobody knows when the Barnacle Club began exactly. Some say 1869, some say 1884, some say later. As a 1922 article put it, “It never had a real beginning, it just seemed to happen.” Pipe-puffing “shellbacks” and Vineyard merchants found a comfortable spot to pass time, play chess or checkers (later, cribbage and pedro), and swap yarns. “As they gathered on the same bench, in the same position day after day, mischievous girls across the street called them ‘barnacles.’”

A 1906 New York Evening Post story declared that the Barnacle Club was “known of mariners from Maine to Florida. Every captain or mate in the coastwise trade may be found there at some time or other during the year.” Another account, from 1914, referred to the group as a “knot of fog-bound skippers.”

In its early years the group was headquartered in the back room of Matthew Chadwick’s cigar and newspaper store, inhabited today by CB Stark Jewelers. In 1904, the forty-four-member club formally organized and elected Sheriff Walter Renear president. The club was moved to the third floor of Lane’s Block (over what is now Leslie’s Pharmacy), and in 1914 across the street to the corner of Main and Church Streets (where Off Main is today). Besides Fisher and Renear, early members included Presbury “Pres” Luce, Captain Hartson Bodfish, Brad Manchester, “Boots” Andrews, Peter Cromwell, Captain Gilbert Smith, Captain George Fred Tilton, and many other notable characters of the day. The club was important enough that in the fall of 1915, when gubernatorial candidate Samuel McCall and his running mate Calvin Coolidge campaigned on the Vineyard before the 1916 elections, their six-town tour ended with a grand reception at the Barnacle Club. McCall soon became the forty-seventh governor of the Commonwealth, and Coolidge, of course, eventually went on to the White House.

The Barnacle Club also served as a museum of sorts, its dusty windows a collecting place for curiosities from around the globe. Accounts from the 1920s mention the stuffed wolverine brought back from the Arctic by Captain Tilton, a golden eagle captured by Gardiner Greene Hammond, a kudu’s horn from Africa, an old Chinese writing desk with a secret drawer, and part of the old telegraph cable that ran from the mainland to the Vineyard.

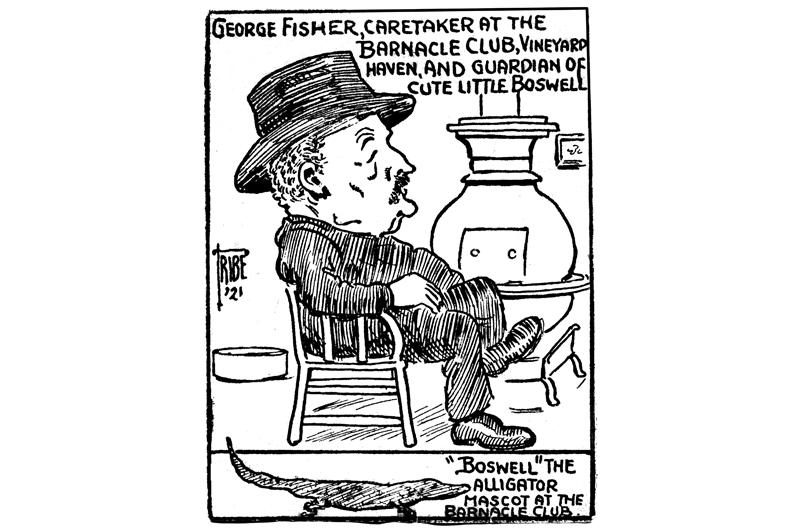

About 1918 Bozzy arrived. The alligator, then about thirteen years old and perhaps two feet in length, was named for the tug Boswell on which he arrived from the Florida Keys. Under the gentle care of George “Goody” Fisher, he soon took the role of the club’s mascot from Spike, a dog who spent his days sleeping on the clubroom floor. On warmer days Bozzy would be found dozing in a pan full of warm water (changed by Fisher five or six times a day) in the club’s downtown windows. At night and in the winter Bozzy slept behind the big base burner stove.

Fisher had spent time in his youth as a steamboat hand, but he had spent most of his adult life on dry land – as a Vineyard Haven meat market salesman and then as the club’s custodian. Fisher “simply dotes on alligators,” wrote the Gazette in 1921, as he demonstrated how Bozzy enjoyed being flipped over and having his stomach and throat stroked.

In the spring of 1921 Bozzy was joined by a second alligator known as Dickey (or sometimes Robbie Dickie), named for Robert L. Dickey, a popular national dog cartoonist who shipped it to the club from Florida as a gift. (Dickey’s illustrations appeared in Life and The

Saturday Evening Post during the late 1910s and ’20s, and he became a syndicated cartoonist in the ’30s.) The two alligators would sun themselves together in the club’s wide windows.

“They love each other now,” noted the Gazette in 1921. “If one alligator is removed to another part of the room, he croaks like a frog until his chum answers.” In 1922, two more alligators were presented to the club by summer Edgartown resident Julien Vose, a piano manufacturer. These two unnamed gators, both hatchlings less than a foot long, had been sent to Vose by parcel post from California.

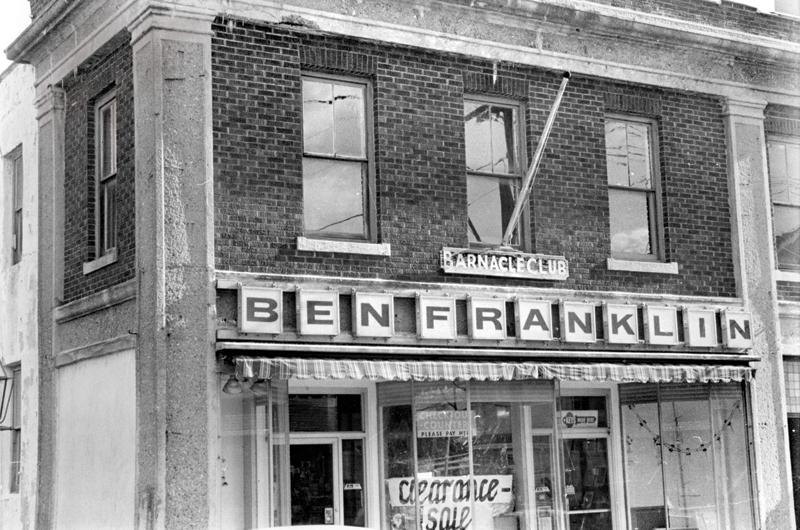

In early 1923 Sam Cronig, head of the new Cronig Brothers grocery firm, bought the building. Three months later, Fisher died at the age of sixty-five. That summer the club moved across

the street to the second floor of Cromwell’s Hardware (later Ben Franklin and today the Green Room). Rather like barnacles, the club would stick to the upper decks of this building for more than a half-century.

“They fasten and they cling, persistently and permanently,” wrote the Gazette. “Sometimes it is to the broad comfortable settee. Sometimes it is to the chairs within the club rooms.” A

new generation of Barnacles joined the club: Charles “Duffy” Vincent, Ben Cromwell, Maurice Delano, Charles Norton, Chester Robinson, Brewer Corcoran, Paul Bangs, L.E. Briggs, Morton Hutchinson, Colonel George Goethals, Carey Luce, Rod Cleveland, Howes Norris, boat builder Erford Burt, Captain James Luce, Captain Chester Robinson, and many, many others. In 1979 rising rents drove them to a new building on Beach Road, then to Five Corners, and lastly to the Bethel. Today the club is in danger of disappearing as quietly as it appeared. Their most recent meeting was a gathering over oyster stew in 2015. (“I’d love to get some help to keep things going,” notes the current president, Alan Wilder of Tisbury.)

It’s unclear what became of the alligators and turtles after Fisher’s death in 1923. The gators were not fond of anyone other than him. “They have a decided grudge against most of the world, and regard only their custodian with some degree of favor,” said the Gazette in 1921. “[Bozzy] regards his keeper with something like affection, although he still eats his food from the tip of a hatpin, lest he mistake a kindly hand for a hunk of the raw beefsteak.”

“You are almost prepared to stroke Bozzy’s knobby back and say, ‘Nice Bozzy, nice Bozzy.’ But you don’t,” echoed another account a year later. “A warning hiss, not at all friendly, warns you that nice Bozzy is not about to purr. And you put your hand hastily into your pocket, instead of into his pan.”

The Real Reptiles of Martha’s Vineyard

Today there are seven species of snakes native to the Island, none poisonous, and some quite rare: the black racer, the green snake, the Eastern milk snake (or kingsnake), the ring-neck snake, the ribbon snake, the garter snake, and the red-bellied snake. There are also a variety of pet snakes of other species in significant numbers on the Island. In 1971 the Gazette reported a sighting of a five-and-a-half-foot boa constrictor swimming in Chilmark Pond. The young snake, named Shunga, was fortunately chaperoned by her owner, a weekend visitor from New York.

Of the native snakes, black racers, sometimes referred to by older Islanders as blacksnakes, are the largest and can measure as long as six feet. “Instances are known of snakes of this species entering farm buildings to rob hens’ nests,” read a Gazette account in 1929, after a huge black racer was discovered in a tree in West Tisbury hunting fledglings. Mal Jones of West Tisbury recalls an old story police chief George Manter once told him about how black racers were collected from stumps in an old Native American tradition. Known as stump eels, the serpents were caught to be eaten.

And they were apparently plentiful. In 1884, newspapers across the country reported that “a man in North Tisbury, Mass., says he has recently drawn up eighty-nine snakes from his well.” But today, snakes and some types of turtles are both in great decline since the

reintroduction of skunks and raccoons, which prey on both the reptiles and their eggs. (The Vineyard’s native skunks and raccoons were both exterminated about 1900. Our original skunks were significantly larger than modern Island skunks, and stripeless; they may even have been a distinct species.)

The snakes are not the only members of the reptilla class. In his 1602 exploration of the Islands, Brereton wrote also of “Tortoises, both on land and sea” here, and “a lake full of small Tortoises” on Cuttyhunk. There are currently four species of terrestrial turtles on Martha’s Vineyard – snapping turtles, painted turtles, spotted turtles, and eastern box turtles – together with five species of offshore sea turtles that occasionally grace our shores. (Archeological evidence of a fifth land-dwelling species, the red-bellied turtle, appeared in Native American kitchen middens excavated in the 1960s in Gay Head and Vineyard Haven, but while populations of red-bellied “cooters” still exist as close as Plymouth, there are none living on the Island today.)

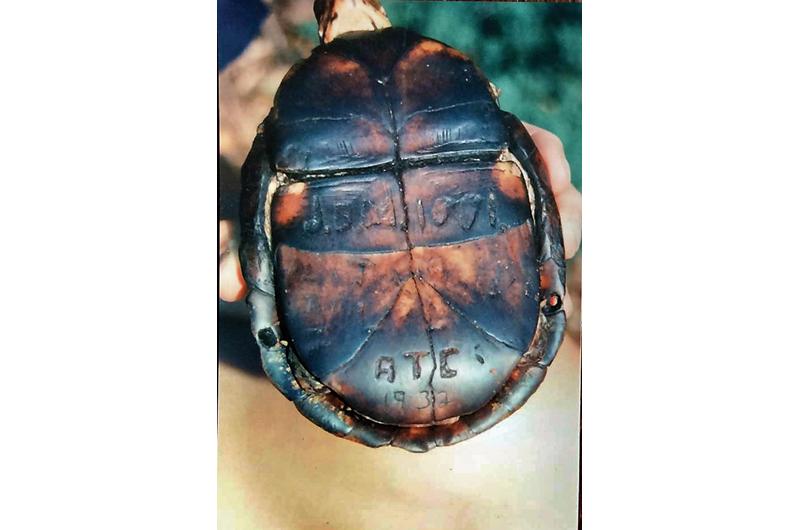

Although turtle life spans are notoriously difficult to determine, box turtles are arguably the longest-lived animal species on the Island. In 1932, a box turtle in West Tisbury was discovered to have “T.A.W. 1861,” “L.P.L. 1861,” and “J.B.M. 1881” carved into its shell. In the 1932 Gazette article, Jerry B. Mayhew admitted to etching his initials into it a half-century prior, and the other two carvers were identified: Thomas A. West and Lewis P. Luce of Tisbury, who both enlisted in the Army and had evidently carved their initials into the shell shortly before leaving to fight in the Civil War. (Neither returned. Luce died of exposure at Baton Rouge in 1863 and West was killed in the Third Battle of Winchester, Virginia, in 1864.) The same turtle showed up regularly in the West Tisbury yard of Tom Hodgson from the late 1980s into the early 2000s, with additional carvings dated 1932 and 1955, implying an age of more than 140 years – a longevity record for box turtles.

Snapping turtles – known on the Island by the misnomer loggerheads (not to be confused with the sea turtles of this name) – are the largest of the Vineyard’s land-based turtles, with specimens weighing up to sixty pounds. Feared for their formidable beak-like jaws, and blamed, mostly unfairly, for preying on ducks and geese prized by sportsmen, they have been widely hunted. Legend has it that Dodger’s Hole on the Oak Bluffs–Edgartown line (originally known as The Dodger Hole) was named for the act of dodging snappers.

Like black snakes, snapping turtles were once hunted – and still are, in some areas; it remains legal to hunt snapping turtles in Massachusetts with a fishing license. Amos Smalley of Gay Head, famous for harpooning a white sperm whale in 1902, was also remembered for hunting snapping turtles for profit during slow winters. Using a long pole and a hook, Smalley and his brother Frank would locate sluggish snappers in the mud and haul them up. The late Craig Kingsbury of Vineyard Haven hunted snappers as well, using baited floats. The turtle hunters would pack their catch live in crates and ship them to buyers in Philadelphia, New Jersey, and the Midwest for twenty cents a pound. “Snapper soup is a big deal in those parts,” he recalled.

Jones remembers Chief Manter hunting for snappers using yet another method: “He would feel them with his feet in the water.” Jones also admits to sampling the rubbery snapper eggs: an acquired taste, he suggests, but adds they were once a delicacy for some. Perhaps in part because the taste was so acquired, their population remains relatively steady. “Snapping turtles are alive and well – they’re in the ponds,” says Vineyard naturalist Gus Ben David, who notes that landowners may not even realize the much-maligned turtles are present. “They’re not conspicuous; they don’t come up and sun themselves.”

Sea turtles, however, are on the decline. Nearly every year Atlantic green turtles, hawksbills, loggerheads, leatherbacks, and Kemp’s ridley turtles make occasional appearances in Vineyard waters or on our beaches. Leatherbacks are the largest, and encountering one must be an unforgettable experience. One caught in 1880 was measured at eight feet long and a half-ton in weight as it was prepared on the Island for exhibition in a museum. Another six-foot, 1,200-pound leatherback, mortally wounded from a boat propeller, was discovered on an Edgartown beach in 1955. Police chief Fred Worden was called to put it out of its misery with his pistol. “I’ve never handled anything exactly like this before,” he told to a

Gazette reporter.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)