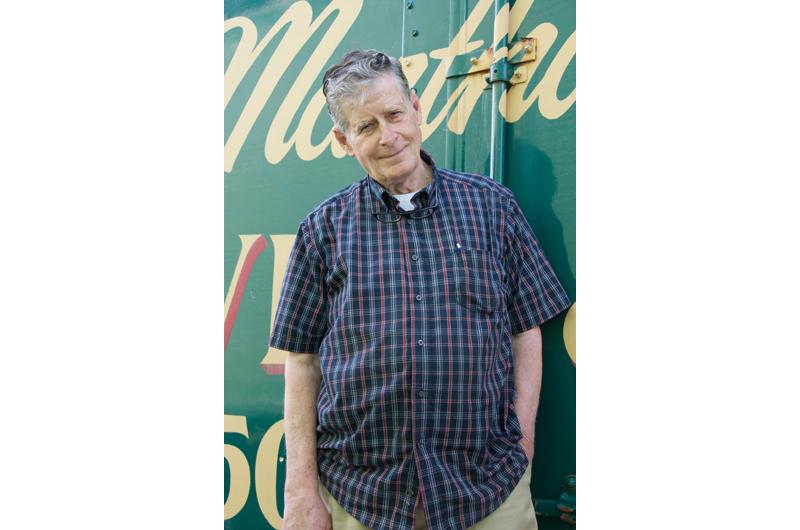

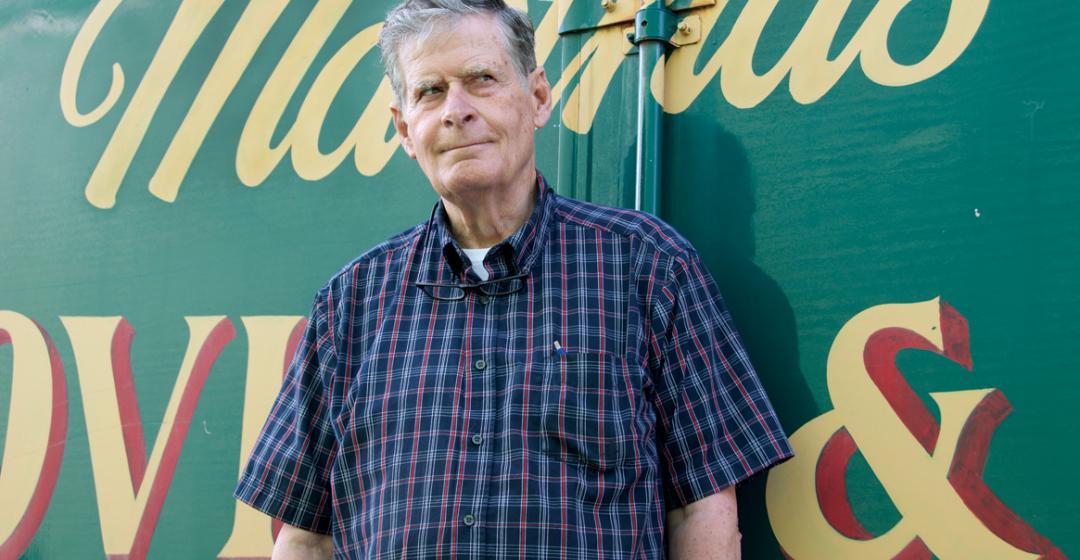

He’s notorious. He’s clever. He’s crafty. He’s the bane of Martha’s Vineyard town officials’ existence. He’s had contretemps at the State House. Every policeman on the Island, and more than a few on various interstate highways, knows him. (It’s a safe bet, in fact, that anyone whose been on the Island for any serious length of time knows him.) He’s a member of

the Martha’s Vineyard Airport Commission, an administrator of the Agricultural Society and of the Preservation Trust, and he led the effort to create a sober house on the Island. He owns five buildings, including climate-controlled storage facilities, fifty moving vans, trucks, and school buses. He’s a used-car salesman, a dealer in obscure items of mysterious

lineage, and a legendary auctioneer for good causes large and small. He’s had three marriages, three children, and three grandchildren. He’s seventy-six years old, six foot two with a full head of hair and a head full of yarns.

On an Island once known more for its characters than its celebrities, he’s a one and only, descended on one side from a Massachusetts attorney general and on the other related to P.T. Barnum. He is, in other words, the Greatest Trip Barnes on Earth.

Barnes is also, in all likelihood, the only Islander in living memory who can claim to have come across not one, not two, but three dead bodies in the course of a winter on Chappaquiddick. Inveterate storyteller that he is, it’s a story he takes a macabre delight in retelling.

“It was in the late fall. I was with Foster Silva’s son John,” he begins. “We saw someone lying by the Dike Bridge on Chappy. ‘Shh,’ John said to me, because it looked as if whoever it was was sleeping. But then, as we drew closer, we could see that it was someone dead, not sleeping. It was Hugh Jones, who owned the Orient Trader store in Edgartown and had designed the Japanese garden at Mytoi. He had his pipe in one hand and his nitroglycerine pills in the other, and $800 in his wallet, but he was dead and I called the police.

“The next weekend, I was back working for Carroll’s Trucking and John was with me this time too. We were on our way to Cape Pogue and John said to me, ‘Hey, what’s that?’

“It turned out it was somebody frozen into his kayak. We couldn’t separate the body from the kayak so we lifted both onto the back of my pickup truck to go to the police station in Edgartown. The body looked just as if he was sitting in his kayak in the back of my truck. It turned out it was somebody from the oceanographic,” he recalled.

A short time later: “In the middle of the day, I was making a delivery to Tony Bettencourt’s on Chappy and there was something behind the door. It was old Mr. Weston, whose family had owned the Chappy Hilton, which got its name during the war because it was where servicemen would be billeted in the war. Of course, I called Hudson Worden, the Edgartown police chief, again, and I told him he’d better get over to Chappy.

“‘Oh, no, not you again,’” the chief said.

Nor are they the only bodies in his repertoire. Barnes also gleefully recounts being in a Boston bar with his friend Peter Mitchell and their girlfriends. Suddenly the bar door opened; a gunman walked in and shot and killed a man sitting near them at the bar. Then the assailant walked out. Since all four Vineyarders were under age to be drinking, Mitchell quickly urged that they all leave, “Why?” curious Barnes asked. “Let’s stay and see what happens. They’re too busy to take any interest in us now.”

Then there was the body being taken out of the apartment on the Upper East Side of New York. And the guy he saw murdered at Fulton Fish Market while delivering fish from the Vineyard late one night. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves here.

His mother, Elizabeth Betts Barnes, had grown up in Boston, moved to New York, and became a model for the Bergdorf Goodman department store, which was where she met his father, Clarence A. Barnes Jr. He was an art director and illustrator for advertising agencies who designed some of the “I’d walk a mile for a Camel” layouts and who later, using the name Clare Barnes, became an author of best-selling sophisticated, funny picture books for adults. His first book was called White Collar Zoo, and some of Barnes’s fondest memories of his city childhood are of his father taking him to the zoo and introducing him to the animals. “He’d ask me what I thought they were saying to each other – things like ‘What do you suppose that elephant is saying to that other elephant about Harry Truman?’”

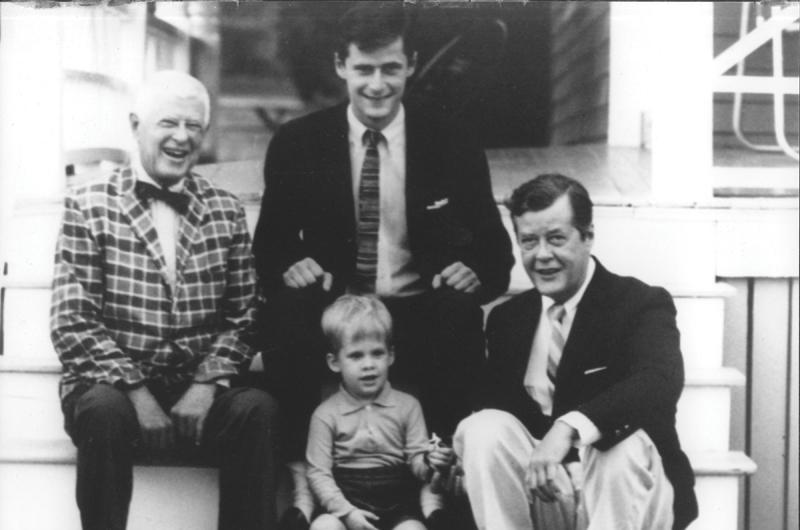

But it was the summers and winter holidays on the Vineyard that really spoke to young Barnes. The family connection dates back to the mid-1800s, when Barnes’s great-great-grandfather, Alfred Smith Barnes of Brooklyn, New York, a leading publisher of his day, built what was then said to be the largest house on Ocean Park in Cottage City (Oak Bluffs). Although the original house reportedly burned down, two others were built by the family on neighboring Waban Park, one of which belonged to Barnes’s grandfather, who was the attorney general of Massachusetts.

Ever proud of his lineage, Barnes likes to tell how Joe Martin Jr. of Massachusetts, who served as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives in the 1940s and ’50s, tried to interest his grandfather in higher office. “I’m not sure exactly how you get to be U.S. attorney general, but Joe Martin wanted him to go to Washington so he could propose him for the post,” Barnes said. “But my grandfather said there was no way he could take the job, even if he got the appointment, because it didn’t pay enough. By that time, my grandmother, Helen Long Barnes, had died and left him with four children – my father, my uncles John and David, and my aunt Jane, who became Jane Moore after she was married. He had later married Doreen Kane, and they had five more children – Sam and Rosalee (who’s now Mrs. David McCullough), Peter and Margot (who’s now Mrs. Neil Goodwin), and Thomas. The U.S. attorney general’s job wouldn’t have paid him enough to support them all, my grandfather reportedly said. After all, he was having to pay college tuition for some and buy milk for baby bottles for others.”

It was a sizable clan, in other words, that vacationed in the home on Waban Park. In the 1940s, with a young family of his own on the way, Barnes’s father spread out, buying the Chappaquiddick estate of John Jeremiah for $1,800. He later acquired more acreage. It was on Chappy, therefore, that Barnes spent his early summers, and by the time he was a teenager he knew he was tired of the city and of school. In Manhattan he had attended the exclusive St. Bernard’s School through the eighth grade, but after one year at boarding school in Connecticut he’d had enough. “The ninth grade was really the end of my ‘proper’ school experience.” (He got his GED from Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School when he was forty years old.) “I didn’t have the freedom in the city that I had on Chappy. All I wanted to do was be on the Vineyard. I couldn’t have a dog or a cat in an apartment, for example, though I did have a hamster, Magsworth.

“He was a beautiful golden hamster,” he says nostalgically. “I built a cage for him and inside it there was a model train station that he lived in. But I’d carry him around in my pocket a lot too. He’d just go to sleep there. And my father even took him to the office in his pocket. He lived to be nine, which is old for a hamster. When he died, I was out on a moving job and my father called to tell me. He’s buried under a stone on Chappy and I visit him there every so often.”

Ready to be a full-time Vineyarder, whenever he could Barnes called his friend Vance Packard Jr., another teenager who also lived in Manhattan but longed to be at his family’s summer home on Chappaquiddick. They’d hitchhike together to the Vineyard and once on the Island, summer or winter, there was always plenty to do. Often as not, the plenty involved driving a truck. (Barnes got a license at the age of fourteen while visiting his maternal grandfather in Florida: “He knew I’d been driving all over Chappy ever since I was eleven and you could get a driver’s license in Florida then at my age.”)

An early employer was William Pinney, the head of the New York Coffee and Sugar Exchange, who had a summer home on Chappy and owned and operated Sweetened Water Farm in Edgartown in his spare time. “He knew me from Chappy,” says Barnes. “He used to rent a Grant Brothers tractor-trailer to pick up the hay bales and then back the whole works into the barn. Jimmy Jackson and Jimmy Gaffney and I were the farmhands. We took turns driving the truck. We’d take it out at night, too, when there was no one on the roads in those days and we’d drive it around town. That’s how I learned to drive a truck.

“Pretty soon I was mingling with people at the Martha’s Vineyard Cooperative Dairy. That Mr. Pinney was the president of too, and then I was driving one of the dairy trucks, delivering milk to the A&P and First National stores in Oak Bluffs and Vineyard Haven, and Garland’s and the Red and White and Tony’s Market and the Reliable and Brad Church’s that’s now Our Market in Oak Bluffs, and Connors’ and Mercier’s in Edgartown, and Cronig’s in Vineyard Haven. There were plenty of markets on the Island in those days, and I was delivering to all the hotels, too. Of course, I met lots of people that way and made lots of friends. I learned how important it is to have friends in the trucking business, if you’re in the trucking business yourself.

“Then I got a job with Carroll’s Trucking in Vineyard Haven. That was because I knew Manhattan well, since I’d grown up there, and Leigh Carroll had to do a lot of moving to Manhattan. It was really Leigh who taught me my trade.

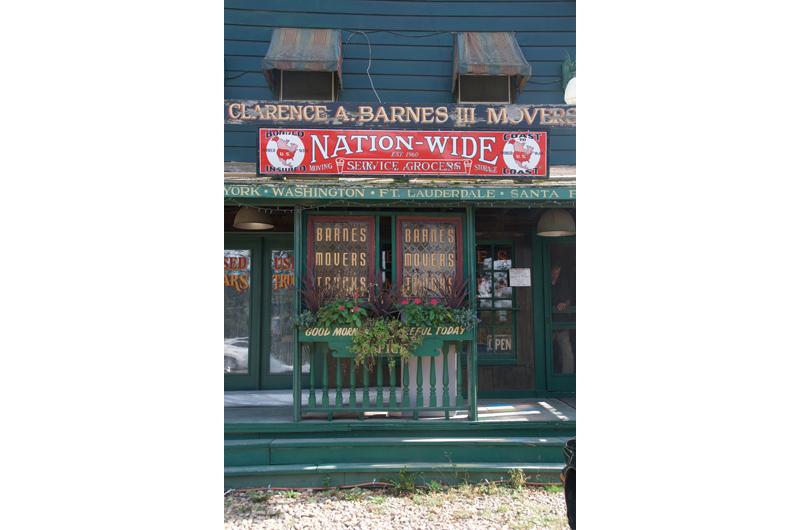

“I got another job about that time too, changing tires at Renear’s Ford Sales in Vineyard Haven. It was the only tire shop on the Vineyard. Bob Carroll was a salesman there in those days. That was long before he had the Seafood Shanty or the Harbor View in Edgartown. That was 1961 and he sold me a 1948 Ford truck for $250. I guess that was the beginning of my interest in buying and selling used cars, and was also the start of the Clarence A. Barnes, III Moving & Storage company.”

“Of course, I had to find a place for us to live. I was having trouble doing that,” Barnes says in his rapid fire way. “Then I was driving past 412 East 72nd Street one day and I saw a

body being carried out of an apartment. I figured that might mean that there would be a vacancy there so I went in and talked to the super. He gave me the name of the owner and

we got the apartment.”

By day he was a truck dispatcher for Time Life, and at night he drove trucks in Brooklyn. He attended the Art Students League and studied life drawing. With a new son, Clarence A. Barnes IV, life was busy. But it wasn’t happy. New York had never been the right fit for him, and Barbara also wanted to be back in New England. So they returned to the Island for a time and he became a tour bus driver for Arthur Ben David and, again, a truck driver for Carroll’s Trucking. Then off-Island again, to a warehouse job in Canton and a car dealership in Foxborough. The problem wasn’t the location, however, and by 1966 the marriage was over. It was time to return to the Vineyard, this time for good.

Two years later, in 1969, Barnes married Judy Cronig, the daughter of Robert Cronig, who, with his brother, David, owned Cronig’s Market in Vineyard Haven. Barnes began trucking for the store, where Judy also worked. Always the Trip of All Trades, he also opened a used-car lot at Bob Bailey’s Corner Service Station in Vineyard Haven and started a business called

Vineyard Pine Lumber that harvested red pines that had been planted in the state forest by the WPA in the 1930s. The company manufactured two-by-fours and four-by-fours,

fencing, and “garden timbers” that were popular at the time. “We dipped the pine in printer’s ink and diesel fuel to make it look the way railroad ties do. They sold especially well at Grossman’s Bargain Outlet.” Out of that venture grew the woodsmen’s contest at the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Fair, which Barnes served as announcer of for some thirty-five years.

Barnes bid on and got the job of removing the Crowell Coal Company and Tilton’s Lumberyard on the harbor to make way for the expansion of the Steamship Authority, after which he got a call from the Martha’s Vineyard National Bank asking if he could tear down the house behind the bank to make room for a drive-in tellers’ station. Barnes convinced the bank president, William Honey, to let him have the house for $1 on the condition that he get it moved quickly to another location. His wife’s uncle, the realtor Carlyle Cronig, helped secure a lot off of Cook Road for $10,000, and it was all looking good until, he recalled, the state denied him the required permit to move the house along State Road because there were too many big trees with overhanging branches. He would have to take the house over the drawbridge and through Oak Bluffs. Or not. After dark Barnes put “henchmen” on trucks and sent them out to trim the tree limbs on the State Road route. At 3 a.m., while fellow Carroll’s truck driver and Tisbury night patrolman Donald Leonard was helpfully patrolling in another part of town, the 180,000-pound, three-story house (its roof taken off) rolled to its new site.

“I guess you’ll have to put me in jail,” Barnes remembers telling Chief Raymond Maciel of the Vineyard Haven police when the chief realized the house had been moved and asked

if he had a permit from the state. To which the chief replied, “Well, let’s wait and see what the state does.”

The state did nothing more than lecture him on the phone and Barnes happily carried on with the business of going off-Island in his trucks to fill the shelves and the refrigerators in Cronig’s: to New Bedford for high-end meats, Boston for produce, Rhode Island for frozen and canned goods. Cronig’s had long occupied the corner of Main and Center Streets in Vineyard Haven, but times were changing. Both the A&P and the First National had developed into supermarkets in downtown Vineyard Haven. Parking on Main Street in summer was becoming difficult. The Cronig brothers decided to move their market to the edge of town and to turn it into a supermarket.

“After that we needed two trailer trucks, then three. Then I’d be asked to pick up a load of cement or of wood or refrigerators for some Island store. I couldn’t do that, of course, in a truck designated for Cronig’s. So I began buying more trucks and more trucks and increasing my business.”

There are almost as many stories as there were moves in those decades and Barnes revels in retelling them. There’s the time he moved Lillian Hellman. The time a truckload of Tom Maley nudes had to go to Copley Square. The time a Steinway grand piano had to be moved out of a Fifth Avenue apartment in New York but would not fit through the door: “So I took it out the window, had the truck backed up, and rode the piano down twelve floors to keep it from striking the building.”

There was the ice skating rink that Islanders wanted but didn’t know how to get. “They talked about it for ages. They had committee meetings. I heard about it and told them I knew that Grossman’s Lumber Company was buying the Walpole Ice Arena to turn it into a bargain outlet. I said I’d ask them if we could have it for the Vineyard. ‘Yes, you can have it if you get it out of here and I’ll contribute $10,000 to the rink,’ Bernie Grossman said. He was a Nantucket guy. Anyway, we got it down here and we’ve had it now for thirty years.”

And who could forget the annual Cat Lift, when Clarence A. Barnes, III Moving & Storage would be called upon to transport Stanley and ABell Washburn’s ménage of cats from their home on South Water Street in Edgartown to their winter apartment next to the United Nations in New York City. Since ABell was the founder and president of the Vineyard’s PAWS rescue program for cats, there were always many felines – both family pets and adoptees – to be transported. “We had a big, chunky old sofa and an old Oriental rug we’d put down for ABell and Stanley, and there might be as many as thirty cats in their carrying cases. Once, one cat got out of its case and we had to find it in the truck by following its meow. I was pulling up at the Steamship Authority while the hunt was going on. ‘Oh, you have the Cat Lift,’ I was understandingly told. ‘You can get right on,’ and that’s how the Cat Lift got its name.”

Another adventure involving the Washburns was when they dispatched Barnes to a warehouse in New Jersey that hadn’t been entered for a half century. Stanley Washburn, an airplane pilot, had been planning to produce airships until the 1937 Hindenburg disaster made it clear there was no future for blimps. Washburn joined the burgeoning Pan American World Airways as director of promotion, but he never forgot the odds and ends he’d left in a warehouse in 1937 and continued to pay rent on it until 1995, when he was informed that the warehouse was to be demolished.

“He gave me the address,” Barnes recalls, “but I had no idea how unsafe the neighborhood where it was was going to be. There were people passed out on the streets. When we got to the warehouse, it was all overgrown around it and it was fenced in. It was about four in the afternoon and we got in and out as fast as we could. There were roll-top desks and 1920s telephones and typewriters and drawings and paintings of blimps and building plans for them. We brought them back to the Vineyard, but then, eventually, took them up to Livermore, Maine, to a museum Mr. Washburn had there.”

And of course, there is that last dead man. “I talked the fish packer, Steve Boggess, into letting us truck the fish he was picking up in Vineyard Haven at Ralph Packer’s pier. We’d truck as much as 80,000 pounds a night down to the Fulton Fish Market in New York. It was largely in the hands of the Mafia then. You’d pull in and then go to the Savoy Lounge and wait for an unloading crew to come and empty your truck. While you waited, they’d ask what you wanted to drink, and you’d sit there and drink while they unloaded. For transactions, you had to have cash. No checks.

“I saw a guy being killed down there once. I backed into a fish house on a lonely dock. Nobody seemed to be there, but then I saw someone with a fish hook in his back and they took him and threw him into the river.”

Sitting and drinking is something Barnes did his fair share of until 1989, when he quit after being stopped in Vineyard Haven for drunk driving. A heavy drinker from his early youth – “I drank like a fish when I was seventeen” – he went to Edgehill, a highly regarded alcohol treatment center in Rhode Island at that time. “It worked. I went to ninety-six A.A. meetings in ninety days. I did everything you’re supposed to do. I really overdid it when I got started – but I got started.”

Not surprisingly, Barnes has stories from his drinking days as well. Once, at the Leeside Bar in Woods Hole, he got to talking with the owner of a Falmouth pet store and asked how much a pair of chipmunks would be. When he was told they were $35, he said he would like a pair for his children. A few days later he picked them up at the pet shop: they had arrived from Miami in an air freight box labeled Live Animals.

“I took them into the Leeside since, as usual, I was waiting for a boat there. When my friends at the bar saw the box, they asked what was in it. I said, ‘Japanese running chipmunks. They’ve run races in Syria and South America. Do you want to see what they can do?’ Of course everyone at the bar said yes, so I opened the box and let the chipmunks out. It took an hour to get them back in, but I did – and made the boat I wanted.

“Of course, I went up to the lunch counter on the boat and I let them out again there, and they were a great success, though it was hard catching them again. Then on the way home, I stopped at The Ritz in Oak Bluffs and I let them out. But there, one escaped and ran out the door and I had to go home with only one. But it wasn’t long before I got a call from Ben David Motors that the missing one had shown up there so I went down after it. By then, my wife Judy had decided they were much too wild to be pets for the children. She said I’d have to take them down to the office – at least until they calmed down. But they never did. They chewed through the wooden window frames and escaped into the back yard and disappeared into the bushes. Ever since then, there’ve been chipmunks on Martha’s Vineyard and, as far as I know, there never were before.

“I had a lot of fun drinking and smoking,” he says, looking back. He quit smoking in 2005. “I have no regrets at all about smoking. I’d probably light up a Camel right now if I was told I was on my way out,” he says, “but I wouldn’t be in the shape that I’m in now. I’ve had open heart surgery and now lung cancer...if it wasn’t for the smoking.

“I was a happy-go-lucky drinker, and my work didn’t suffer from it, but I could probably have expanded and done more if I hadn’t been drinking. It held me back, but I was a functional alcoholic. The first time I was stopped for drinking was that time in Vineyard Haven, just three blocks from my office. I went across the yellow line.…I made a lot of friends drinking, but I’m not wild now about going out and making new friends.”

Ever enthusiastic, Barnes becomes serious when describing what he believes is his most valuable contribution to the Vineyard, his role in the creation of a sober house. “There’d been something called the Captain Silver House that had been a sober house, but it was long gone,” he recalls. “I knew the Island really needed one, so I started one over my office. Then one day I had a call about someone who was willing to put money into an Island sober house because her son was an alcoholic who needed help and she had money that could provide the help. We ended up getting $300,000 for a house in Eastville in the early ’90s.

“I got together a couple of alcoholics to help clean up the place. We had ten rooms and we decided to call it Vineyard House. At first neighbors complained. They said we needed a rooming house license and didn’t have one; I put on a shirt and tie and went to the neighbors and told them the house we had was for people who don’t drink, not for drinkers, so they shouldn’t worry. But it wasn’t long before we got another sizable sum from the late Walter Scheuer, and then we bought the Donald A. Roberts house across the street from the first Vineyard House. We needed a president so I became the first president. Those houses have been replaced now by brand new sober houses in Vineyard Haven.”

By the time he lead the effort to create Vineyard House Barnes had already, in all likelihood, raised more money for more good causes on the Island than anyone else. It started in the early 1970s, when Tim Chilton of Vineyard Haven, who commuted daily to Falmouth, began talking with Barnes on the boat. He told him how much the Boys’ & Girls’ Club meant to his children and said he’d like to raise money for it and was thinking of having an auction.

“Since you know everybody on the Island, why don’t you be the auctioneer?” Barnes remembers him saying. “We can auction off things like a trip to New York or going for a sail with Walter Cronkite or playing tennis with Mike Wallace.”

“And so we did it,” Barnes says, “and we had a great time and made a lot of money. Tim was right. I could call everybody by name and that made a world of difference. Then I did an auction to raise money for youth hockey. We had that auction at the Mansion House in Vineyard Haven and sold beer and wine and we made a lot of money at that auction too. Pretty soon I was doing auctions to benefit the Preservation Trust. At one of those, I sold a Ray Ellis painting for $250,000. At another auction, I said that Ray – who really cared about the Preservation Trust – would do anything for it. I said, ‘For $4,000 he’ll take his shirt off, and his shoes for another $2,000.’ We got all the way down to his underpants!

“At a Bobbie Burns dinner, I auctioned off deeds to square inches of the Chappaquiddick Estates that actually are in Vineyard Haven, not on Chappy. We had Sail Martha’s Vineyard auctions at the old DAR House in Vineyard Haven. Then the Possible Dreams auctions to benefit Martha’s Vineyard Community Services began. Art Buchwald was the auctioneer for them and a lot of people went to them just for him, but after he died I began doing them, and we did pretty well then, too.”

Barnes’s generosity is not just public. He has a long history of quietly hiring young employees, many of them in challenging life circumstances. And he is renowned for his loyalty over the long haul of life to those workers. One he remembers particularly well is the late Horatio Malonson of Aquinnah. He had attended the American School for the Deaf, Barnes recalled, but had only a limited use of sign language and could not speak.

“But he was a wonderful guy,” Barnes recalls. “One day he wanted to know if he could go with me to New York, where he had a girlfriend he’d met in the summer. I said ‘Sure.’ I thought I could show him a bit of the city and he could spend time with his girl. On the way back, he let me know that he’d like to work for me. He had a lot of strength. He never complained about anything. I figured we could use him one way or another. It turned out what he really wanted to do was to drive, so I taught him to drive a trailer truck. He could manage because he could feel the vibrations. And he got a license and I’d have him driving at a time when there’d be another truck going too. Once we stopped someplace down South to get gas and he got out of the truck and went to start pumping gas, and someone from the station screamed at him because he was dark-skinned and called the police. When they came, the police couldn’t believe that he was really deaf and dumb and was a truck driver, but he was a wonderful man and very good driver.”

At least that time the truck ran. When Dan West, longtime owner of the Machine and Marine in Vineyard Haven, and his wife Kyra moved to Maine, the Barnes truck managed to get on the ferry to North Haven Island but had to wait until two four-wheel-drive trucks could be rounded up to pull it off the boat. “By that time it was dark,” West recalls, but with a flashlight they figured out that somehow during the ferry ride the gas pedal had become disconnected. “The only way we were going to get the load to the house was if I got on my hands and knees on the floor of the truck – sort of underneath the driver’s knees, and operated the throttle by hand. We proceeded that way the four or five miles to our house. While we were traveling, of course, I couldn’t see anything, and since I was operating the throttle I had to know when to go slowly and when to speed up, so the driver would have to call to me ‘Slow down’ or ‘Speed up.’”

But the story West tells that probably best sums up both the Barnes way of doing business and the Vineyard’s way of loving Trip Barnes is about the time he was supposed to pick up eight Sunfish sailboats in Falmouth to bring to the Vineyard. “Suddenly I got an hysterical call from Falmouth,” West recalled recently. “‘There’s a guy here who’s stealing your boats. He’s piling them onto the top of a cesspool truck and he’s ready to take off!’”

“‘That’s okay,’ I said. ‘That’s Barnes Moving & Trucking from the Vineyard.’”

10 comments

10 comments

Comments (10)