Now every living thing seems to be on the move. Ospreys have begun to leave for southern climes. The bass that in August spread north to Maine and Nova Scotia are on their way back south past the Vineyard in time for the fall fishing derby. Schools of bonito and false albacore are also passing through. Monarch butterflies are in the midst of breeding; soon their offspring will continue the next leg of their migration toward central Mexico for the winter.

Come September even most of the resident humans have decamped to their winter habitats in California, New York, Boston, Florida, or various warm locales. A rarer few humans are moving in the opposite direction, back home to the Island after having fled the crowds or cashed in by renting their home for the high season. Still others are doing the Vineyard Shuffle, relocating from their summer digs to their winter nests.

Migration has always fascinated people. Until 150 or so years ago, many thought that birds dove down to the bottom of ponds in the fall and stayed there through the winter. It made sense; the birds were often last seen near water and then reappeared near water the following spring. Others seriously believed that birds flew to the moon, or morphed into other species during the winter months. We know better now, but we are still learning: it was only about five years ago that scientists figured out that most of the piping plovers that breed on our beaches (and elsewhere along the Atlantic coast) spend their winters in the

northern Bahamas.

The distance traveled during migration varies depending on the species. Some are very short: pinkletinks move maybe a few hundred yards from the ponds in which they are hatched to the surrounding woodlands where they winter. At the other extreme are Arctic terns, which nest in the Arctic and winter near Antarctica; they circumnavigate the globe and travel 25,000 miles per year, experiencing two summers.

On any given day, most animals move relatively short distances from one patch of resources to another, often changing from feeding to vigilance to resting and back again. These daily commutes can be astonishing in their own right: in the waters around the globe, including the Vineyard, plankton, the microscopic plants and animals that form the base of most marine food webs, rise at night to near the surface of the ocean, but in daylight descend to 800 meters below the surface. This extraordinary commute involves more biomass than any other migration and occurs throughout all oceans and in large freshwater lakes (about 70 percent of the earth’s surface).

Seasonal migration, however, typically involves longer distances, and migrants often travel past resource patches that would normally be explored and utilized on a daily basis. Migrants also change their behavior well before the journey starts, eating voraciously and storing the extra food as fat to fuel their long-distance travel. If these behavioral changes are not started and completed before food resources become scarce, the migrants may not accumulate enough fat to power their journey.

Once migration begins, an animal’s activity patterns may change again. A songbird is normally active during the daytime and sleeps at night, for instance, but its sleep habits are reversed during migration, when it feeds and rests during the day in order to fly through much of the night.

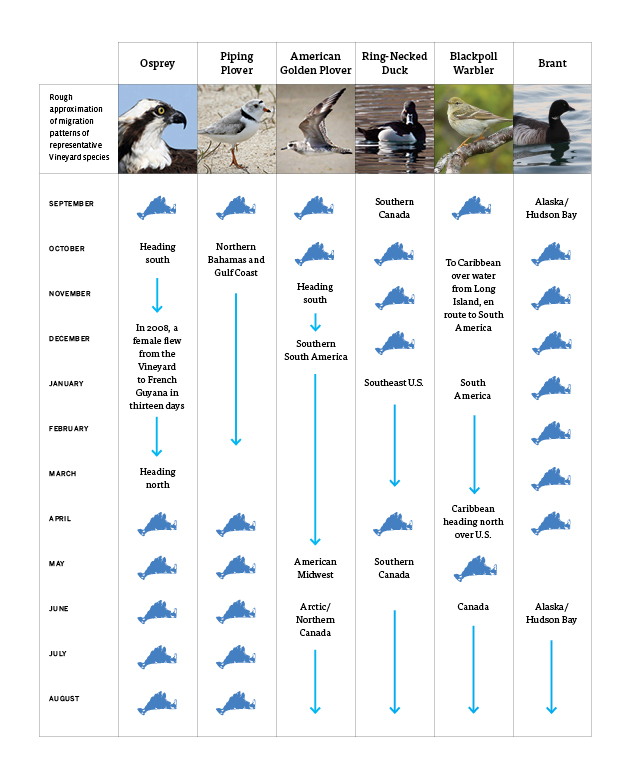

Although we often talk about spring and fall migrations, these terms are misnomers. The so-called “fall” migration actually starts in July, when American golden plovers and other shorebirds leave their Arctic breeding grounds, heading toward the Vineyard and the Atlantic coast. Ducks, too, begin to head our way from points north. In August the familiar songbirds start gathering up in Aquinnah, to be joined by compatriots from farther north, all of them preparing to head west toward New York, New Jersey, and points south. The movement continues until about January. Then, just one month later, the “spring” migration starts and continues into early June.

The truth is that many migratory species are on the move for most of the year. Rather than fall and spring migrations, therefore, northward and southward migration might be better terms.

Still, it is undeniably in the fall that the Vineyard feels near the center of this process, since it is then that so many species pass through. During the northward migration, many birds travel up the middle of the country along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, to take advantage of the prevailing southerly/southwesterly winds. If they were to fly northward up the Atlantic Coast, the springtime’s frequent north/northeasterly winds would hinder their flight.

In the fall, on the other hand, migratory birds breeding from Alaska to Atlan-tic Canada tend to migrate southward along the East Coast. Along this route, the Vineyard is a natural place to stop and refuel. A yellow-rumped warbler breeding in Alaska, for example, will cross the continent, riding the northwest winds that are prevalent after a cold front passes through. When it reaches the Atlantic coast – likely the Vineyard – it will stop, because to continue would carry it out over the Atlantic Ocean, and

the songbird cannot swim.

It pauses on the Island and gorges on bugs and berries until it is strong enough to continue

onward, this time migrating westward along the coast toward New York and New Jersey, where it will resume flying southward. By contrast, a yellow-rumped warbler breeding on Prince Edward Island is already on the coast, and will simply follow it toward the south and west, perhaps with a brief stop on the Vineyard.

That the Island entices so many of these long-distance migrants to pass through every fall makes for spectacular birding at this time of the year. More than one person, myself included, migrated to the Vineyard thinking he would be a temporary visitor only to stay because of the tremendous diversity of birds and wild nature that are here in the fall. And more than one person, it’s safe to assume, came to the Vineyard to fish for a fall weekend and later figured out a way to stay.

But when the birds and fish and other nomadic creatures leave…where do they go? And why do they come back?

Birds do it:

If you’ve visited the Arctic in the summer and have experienced the extreme abundance of berries and insects, including mosquitos, you know why shorebirds might make the trip there. If you’ve been to the Arctic in the winter, you know why the birds leave. The same is true of the Vineyard, where abundant sources of protein from spring through fall enable birds to thrive and raise their young. But the fruits have mostly been consumed and the insects are dormant by the time winter comes. Before seasonally abundant food sources become scarce, therefore, they must head back south to warmer climates.

The real question, it would seem, is why do they leave the warm, food-rich southern climates in the first place? After all, there are a lot of year-round residents in the tropical regions where many of these migrants end up for the winter, and there seems to be enough food to go around. It turns out that birds coexist in the off-season because they are not territorial; they may even congregate in large diverse flocks just as they do when migrating past the Vineyard.

However, the year-round residents of the tropics become territorial during their breeding season in order to ensure they have enough food resources to raise their young. This territoriality displaces the migrants and causes them to leave their wintering grounds and migrate back north, where food is once again abundant and there are fewer year-round residents in competition.

Once humans figured out that birds weren’t hiding in the bottom of lakes or flying to the moon, they began to wonder how the animals navigate with such accuracy. In the fall, for instance, individual adult ospreys migrate from the Vineyard to a particular location in South America. In the spring, most of them return to the same pole that they nested on the previous summer, especially if they successfully fledged at least one chick.

Nor does every winged traveler from the far north that passes by the Island in the fall simply turn when it reaches the ocean and follow along the coast for the rest of the journey south. American golden plovers have a unique migration route: like many other species they migrate northward in the spring across the central United States. On their southward migration from the Arctic, they take advantage of the northwest winds prevalent after a cold front passes through and ride them to Martha’s Vineyard or elsewhere along the North Atlantic Coast. Like other transient birds, while here they feed heavily to prepare for the next leg of their migration. But instead of turning down the coast with the crowd, they ride these same northwest winds far out over the Atlantic Ocean until they reach the tropics, where they make a right turn and ride the northeast trade winds back toward land until they reach the coast of South America.

That’s an impressive gamble for a ten-inch bird that weighs about five ounces. But believe it or not, the tiny blackpoll warbler also utilizes an oceanic migration route in the fall. This 5.5-inch-long bird weighs about half an ounce – think three nickles – but eats enough food while here to store adequate fat under its breast feathers to power a nonstop flight from our shores to the Bahamas, Florida, or even South America. Blackpoll warblers cannot swim, so if they run out of fuel they become fish food. Weakened blackpolls have been known to touch down on boats, staying onboard until they are within sight of land.

There is much that is still unknown, but scientists believe there are a variety of tools that birds use to help them navigate their long journeys. Ospreys have excellent vision – equivalent to ours when we use binoculars – and migrate mostly during the daytime, so they can use features of the landscape such as rivers, mountain chains, and coastlines to guide their navigation. Some of them do fly out over the Atlantic Ocean, passing through Bermuda on their way south, or leaving the Mid-Atlantic coast for the Bahamas and then on to South America. Being primarily daytime migrants, it’s thought that they use the sun’s location to help them orient their flight direction even on these long oceanic flights.

Nocturnal migrants, such as our songbirds, orient their flight based on where the sun set, but they also use visible features of the earth’s surface to help them navigate, even at night. Songbirds migrating toward the Vineyard from the northwest in the fall use the ocean to orient themselves and continue their journey along the coastline. These visual cues are so important that the birds actually stop traveling when they encounter fog or low clouds.

Many birds also use an internal compass to orient themselves. The effect has been observed in caged birds, who tend to hop in a consistent direction at dusk at the times of year they would normally be beginning their migratory flights. When researchers reversed the magnetic field in the laboratory, the caged migrants hopped in the opposite direction.

Despite all their tools, some animals do get lost. Perhaps their wires get crossed so they cannot navigate properly, or maybe they get carried off course by storms. This is why we get so many vagrant birds – species that do not normally live here – on the Vineyard. The best example of this vagrancy is the red-footed falcon that visited the Island for about two weeks in August 2004. This bird was probably migrating between its wintering grounds in southern Africa and its European breeding grounds when it lost its way. Somehow it ended up here, becoming the first and only sighting of this falcon in North America.

Fish do it:

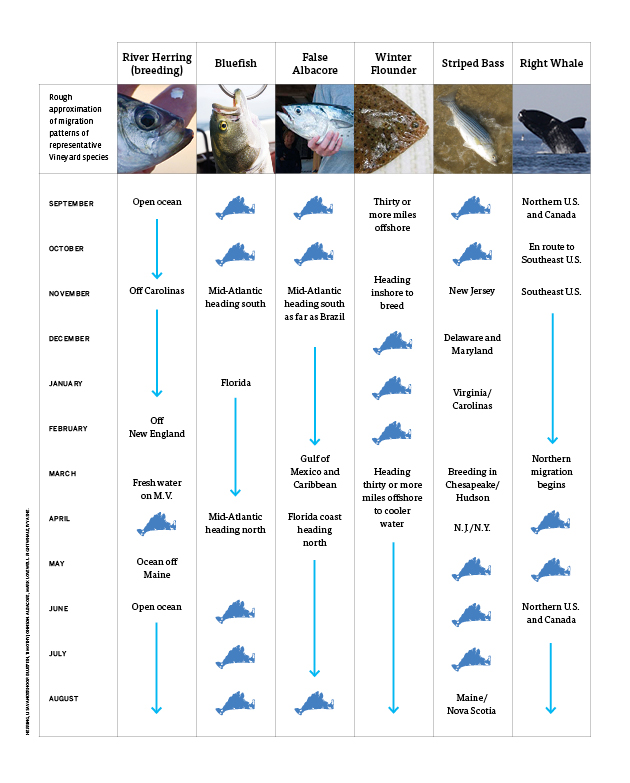

Every Vineyard sport fisherman knows that the favorite game fish come and go according to the season. The striped bass are usually the first to arrive, on their way up from breeding grounds in the Chesapeake Bay or in the Hudson or Delaware Rivers. (A few usually overwinter in the Great Ponds.) The small “schoolies” lead the way, sometimes arriving as early as mid-April, followed a month later by the first small keepers. By June the large bass are usually here, on their way toward Maine.

While the availability of food – squid, herring, sand eels, and other bait – is clearly vital, the driving force for the migration appears to be water temperature. Stripers prefer water between 55 and 68 degrees, and move north and south, inshore and offshore, to stay within that range. In August, therefore, when water temperatures peak around the Vineyard, there is often a lull in the bass fishing, as most of the fish have moved on to cooler waters north of the Cape. By Derby time, they (hopefully) return as they make their way south to breed.

Bluefish prefer slightly warmer water, from 64 to 72 degrees. Not surprisingly, therefore, they tend to show up later than the bass and stay more reliably through the heat of the summer. Predictably, perhaps, they winter farther south than bass, spreading out below Cape Hatteras to Florida. False albacore and bonito like water around 70 degrees, which is reflected in their season in local waters and their winter range. Water temperature is also a factor in the migration of tautog inshore to breed in the summer and then back offshore in winter to deeper waters where the temperature is more consistent. Winter flounder, by contrast, come inshore in winter to breed.

Marine animals use some of the same tools that birds do to navigate. For instance, both fish and sea turtles have been shown to use the earth’s magnetic fields to help find their way. Leatherbacks, which regularly appear in Vineyard waters in late summer to feast on jellyfish, also have a “skylight” on their skulls that researchers think may allow them to sense the changing length of day.

Some fish have navigational skills that birds have not yet been shown to have. The local river herring – a common name for both alewife and blueback herring – can detect chemical cues in their environment, using their sense of “smell” to guide their migration. These herring are anadromous, which means they breed and lay their eggs in fresh water, but spend most of their lives in the salty ocean.

When young river herring are hatched, one of the earliest stages of their development includes imprinting the unique chemical composition of their natal stream. They stay in those streams for three to nine months, migrating downstream toward the sea once water temperatures start to decline with the arrival of fall. Their physiology gradually changes to allow them to live in the chemically very different salt-water environment, and they join the adult alewives already living in the Atlantic Ocean.

After three to five years of migrating up and down the Atlantic coast, they use the earth’s magnetic field to navigate back to the general vicinity of their natal waters, where their imprinted memory takes over, allowing them to follow chemical cues up the stream to breed near the exact spot where they hatched. The adults then return to the ocean. They may repeat this annual migration to breed several times before they die.

Local eels, being catadromous, do the opposite. The eels you see in the headwaters of the Great Ponds spend the majority of their lives in fresh water or estuaries. But they weren’t born there. Instead, they hatched into larvae in the Sargasso Sea, thousands of miles away,

in the mid-Atlantic Ocean south of Bermuda and east of the Gulf Stream.

Larval eels drift slowly inshore on ocean currents before transforming into nearly transparent glass eels, which make their way into the fresh and estuarine waters. Once in fresh water they darken and mature, becoming first elvers, then yellow eels, and finally silver eels. At that stage they return from all over the Atlantic coast of the Americas to the Sargasso Sea to breed, spawn, and die.

Even prehistoric crabs do it:

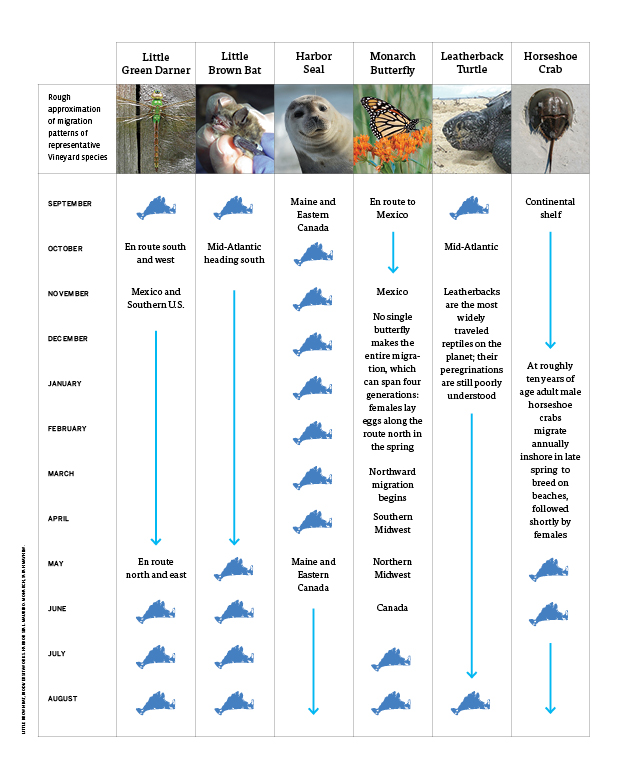

Being an island puts a significant crimp in the migration of terrestrial animals – other than humans and their attendant pets, of course. There is anecdotal evidence of an internal skunk migration from the protection of the woods in winter down to the summer smorgasbords of the beaches and, some say, of Main Street, Vineyard Haven. The elusive beach tiger beetle, meanwhile, makes an annual trek from its underground burrows in the dunes down to the waterline for the warmer months of summer.

Whales and harbor seals, too, are predictably nearby in certain times of the year and not in others. Lucky boaters in Vineyard Sound might cross paths with a peripatetic giant leatherback gorging on jellyfish in the height of summer, and unlucky green turtles might find themselves in need of a rescue from the beaches of Cape Cod when the waters turn cold.

Numerous crustaceans, including lobsters, horseshoe crabs, and blue crabs head offshore in winter. Adult American lobsters move into warm, shallow waters near the coast in the summer because there is more food and they can grow quickly. They use the decreasing water temperatures and the arrival of winter storms as cues to migrate back to deeper offshore waters, where the temperature is more constant throughout the year. Though they remain active in the deeper waters, both their metabolism and their growth rate slows. Then, in the late spring, the higher sun, longer days, and warming water triggers the lobsters to migrate back to the nearshore where they can be more active.

Every creature, it would seem, is following its own internal clock, reacting to its own set of environmental cues. But every piece is interconnected in ways that scientists are only starting to understand. A devilish unplanned experiment called global warming is taking place with unpredictable and potentially dire consequences for migratory species.

For instance, adult horseshoe crabs live most of the year in the deep waters near the continental shelf. As with lobsters, seasonally warming ocean temperatures trigger their migration into shallow water, where they breed on protected coastal beaches during the higher tides associated with the full and new moons of May and early June.

A different set of cues – changing day lengths and cooling air temperatures – triggers the migration of the red knot, the largest North American “peep” and an occasional transient on the Vineyard. Red knots annually migrate from Tierra del Fuego near the bottom of South America to the Arctic north, and rely on a bonanza of horseshoe crab eggs to fuel the journey. Because ocean temperatures are rising faster than the other cues are changing, the eggs may be laid earlier and get eaten by other animals before the red knots get there.

If that happens, the red knots may not have enough fuel for their northward migration. No one knows what will happen with this unplanned experiment, but the results of uneven warming are unlikely to favor the red knots and other travelers that rely on resting spots such as the Vineyard to be well stocked with food for the next leg of their journey.