On a bright but brisk Sunday afternoon, Margaret Gonsalves Oliveira pulled her car off a dirt road on the island of Chappaquiddick and tromped through the woods to a small clearing, where reside the graves of a half-dozen Native American notables from long ago.

In a sense, this site, hidden from the road, could serve as a metaphor for Oliveira’s tribe – not quite lost but nearly forgotten. She’s a member of the Chappaquiddick Tribe of the Wampanoag Indian Nation, which exists in low profile, especially when compared to the Aquinnah tribe on the western edge of Martha’s Vineyard and the Mashpees on the mainland, both also Wampanoag and the only two federally recognized tribes in Massachusetts.

Oliveira and about 300 other enrolled members constitute the Chappaquiddicks, and while they share many cultural similarities – as well as relatives and friends – with the Aquinnahs and the Mashpees, there’s one key distinction. The Chappaquiddicks today have no tribal land of their own. Largely because of that, and the resulting diaspora of members, until some twenty years ago they were on the verge of ceasing to exist as a formal community.

“The connection to the land – there’s something about that,” said Jim Peters, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and executive director of the Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs. “I have that myself [as a Mashpee]. It’s in the blood. When you think about all the people who have come here from other countries, there are only very few of us who really can say we have a blood connection to the land. We [natives] were here first – and for a very, very long time.”

The lack of tribal land and the federal recognition that often goes along with it also means that the Chappaquiddicks, like several other so-called “historic tribes” in Massachusetts, exist largely out of the public eye.

“A lot of people don’t believe there are any indigenous people in the state unless there’s a casino involved,” said Cedric Woods, director of the Institute for New England Native American Studies at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. “That’s usually where it starts and ends. I can’t tell you how many of the students come in with utter ignorance about

individual [tribes] in Massachusetts. So for communities like the [Chappaquiddicks] that are looking to revitalize there, it’s really an uphill struggle.”

Or, as Oliveria put it, “A lot of people don’t know we exist, don’t know we’re here. I still think a lot of my friends, Aquinnah Wampanoag, they don’t realize that I’m different, that I’m Chappaquiddick.”

In fact, until her twenties, she herself didn’t even know. Growing up in Gay Head (Aquinnah), she was steeped in Native American heritage and spent first grade in Helen Manning’s class, surrounded by Gay Head tribal members. “I remember just having the pride of being a Wampanoag,” she said. “My mother always knew that her family came from Chappaquiddick. She didn’t really know there was any difference.”

When the first English immigrants – perhaps the original wash-ashores – took up residence in the early 1640s in what is now Edgartown, Martha’s Vineyard had several separate Wampanoag settlements that amounted to about 3,000 people, from Gay Head in the west to Chappaquiddick in the east. They had been living on the Vineyard since before rising seas from the receding ice age made it an island six to seven thousand years ago.

It’s likely they were not particularly surprised by the arrival of the colonists: it was Wampanoag cousins of theirs, led by the Sachem Massasoit, who welcomed the first Pilgrims to Plymouth two decades earlier. Even before 1620, one of their own, Epenow, had returned to the Vineyard after being enslaved by an English trader and taken to England for several years.

The island of Chappaquiddick (derived from the Wampanoag word tchepi-aquidenet, or “separate island”) was led in the 1640s by the sachem Pakepanessoo, who is said to have wielded firm authority over his people and conducted the tribe’s relations with the English arrivistes. The Mayhew leaders of the colony were committed Christian missionaries, and while Pakepanessoo was initially critical of those of his tribe who converted to Christianity, he too became a believer, it was said, when he was nearly struck by lightning and one of the converts rescued him.

Nevertheless, interactions between the Chappaquiddicks and the colonists were not always friendly. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the disputes most often involved land. Specifically, the colonial imperative to commodify land as property belonging in perpetuity to a specific individual was incompatible with the native culture’s more communal approach to territory. At the time of Pakepanessoo’s death, believed to be in the late 1600s, about

140 Wampanoag were living on the island of Chappaquiddick, and roughly 200 colonists were across the harbor. In a familiar story for the majority of Native American nations across the continent, over the course of the next four centuries, their

communal land would shrink to virtually nothing.

The taking of the island of Chappaquiddick was not achieved militarily. Rather, it was a piecemeal process facilitated by land values, property taxes, speculation, and debt. “By the eighteenth century, most native peoples are debt peons of the English,” said David J. Silverman, professor of Native American history at George Washington University and

author of Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity and Community among the Wampanoag Indians of Martha’s Vineyard, 1600–1871. “So they can either sell their land or their own labor or that of their family to fend off their creditors in court.”

It got so bad that the Chappaquiddicks had a petition of their grievances hand-delivered to King George III in the early 1770s – but, as the story goes, the king’s resulting order fell on deaf ears among the colonials, who were flouting the home country’s instructions by then. Indeed, in the Declaration of Independence a few years later, one of the Americans’ specific complaints was that the king was “raising the conditions” required for taking land away from Native Americans.

In the newly independent Massachusetts, a system of state-appointed guardians supposedly protected the interests of Native Americans, deciding whether their land could be sold. But the fix seemed to be in: town officials and merchants wielded political and economic power, as well as the judicial power to enforce it. “Some [guardians] are doing the best they can,” said Silverman. “And many others are fleecing natives of their land. It became particularly bad on Chappaquiddick…when you have creditors, courts, and land-grabbers doing whatever they can to extract every last resource out of these people.”

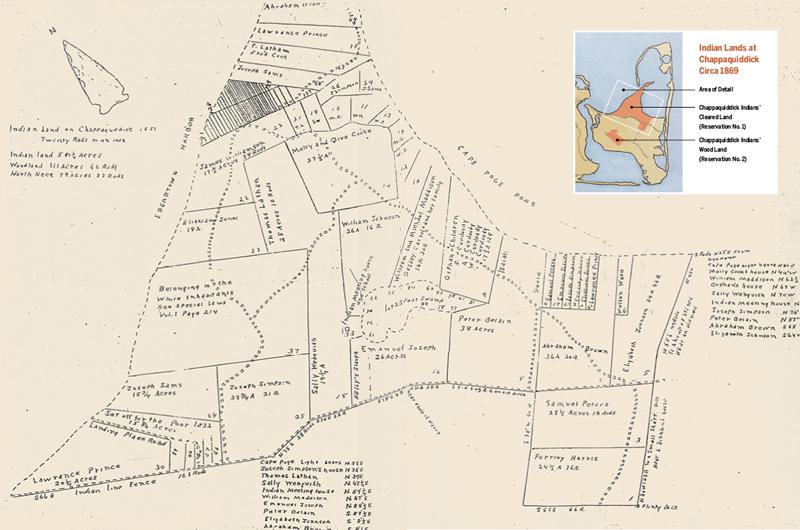

As tensions between natives and settlers persisted, the state legislature divided the island in 1788, leaving the tribe with about one-fifth of the land, in two reservations. In 1828, the reservations were further divided among the seventeen Wampanoag households on the island, according to various histories.

Many Chappaquiddicks were forced to move away for work – sometimes conscripted on whaling ships – to support their families. Although its precision as a census is questionable, one of the state’s periodic reports about the size and condition of the Native American population reported that in 1849 the largest concentration of Native Americans on the Vineyard was already in Gay Head with 174 tribe members, followed by Chappaquiddick with 85 members, and Christiantown with 49. According to the report, the Chappaquiddicks were then living on 692 acres, “on a bleak exposure, and the soil is barren, and yields a precarious subsistence to the most unremitting industry.” By comparison, the Gay Head tribe occupied 2,400 acres.

With the end of the Civil War, Massachusetts adopted a new approach to the “Indian problem.” The ratification of the fourteenth amendment in 1868 granted suffrage to all male citizens, and the notion of Native Americans as wards of the state became outdated. The Massachusetts Act to Enfranchise Indians of 1869 granted full citizenship status, but also converted communal land into individually owned parcels. According to Silverman, in the eyes of most Native Americans, full U.S. citizenship and individual landholding status was viewed as an imposition, not a gift, as their reservations were broken up and communal culture atomized. What they wanted was sovereignty, he said. “Independence and sovereignty.”

The Aquinnah and Mashpee tribes managed to stay together and keep their land, in part because when Gay Head and Mashpee were incorporated as towns in 1870, virtually all their residents were tribal members. The island of Chappaquiddick, on the other hand, had long been a part of the town of Edgartown, where white settlers easily outnumbered them.

It would be patronizing, even insulting, to suggest that there weren’t Chappaquiddicks who did not freely and fairly divest themselves of their real estate down through the years. But historians, both white and Native American, suggest that there also was an inexorable, often government-sanctioned divestiture for three centuries. “In order to break down the native, communal way of land, you partition off the land, allot the land off to individuals, and see if they can hold on to them,” said Peters. “Then you’d tax them, or let them take out loans and so forth, and they would end up losing it because they couldn’t generate money in order to pay for it, or even understand the whole concept of ownership in that way.”

Contrary to the universal mythology of conquest, people don’t “disappear” when they lose their land. Nonetheless, nearly four hundred years after the permanent arrival of Europeans in New England, it’s a wonder of sorts that any tribes without tribal land have survived at all.

By the mid-twentieth century, there were virtually no Chappaquiddicks living on the island, said Alma Gordon, the tribe’s sonksq (female sachem). Furthermore, the number of parcels owned outright by persons connected to the tribe was dwindling. Intermittent efforts in federal and state courts to reclaim any land were unsuccessful, including a sweeping lawsuit undertaken by the various Wampanoag tribes to reclaim lands on the Vineyard, the Cape, and Nantucket that was rejected by the federal courts in large part because they were not recognized by the federal government as tribes. (The Aquinnah gained recognition in 1987, the Mashpees in 2007.) Individual efforts in state courts to reclaim family parcels on Chappaquiddick also largely failed.

“If we had had our own town, chances are some people would have remained, or maybe given us a firm handle on our community,” said Gordon, who has also served as tribal historian and goes by the tribal name White Sky.

But despite the legal setbacks, or maybe because of the communication required to pursue the cases, various families with tribal roots kept in touch. The families – Rocker, Healis, Handy, Curtis, Brown, Freeman, and Epps – kept some continuity alive, said Gordon. And about twenty years ago, an effort to regain a more cohesive status – in effect, a tribe – began to coalesce.

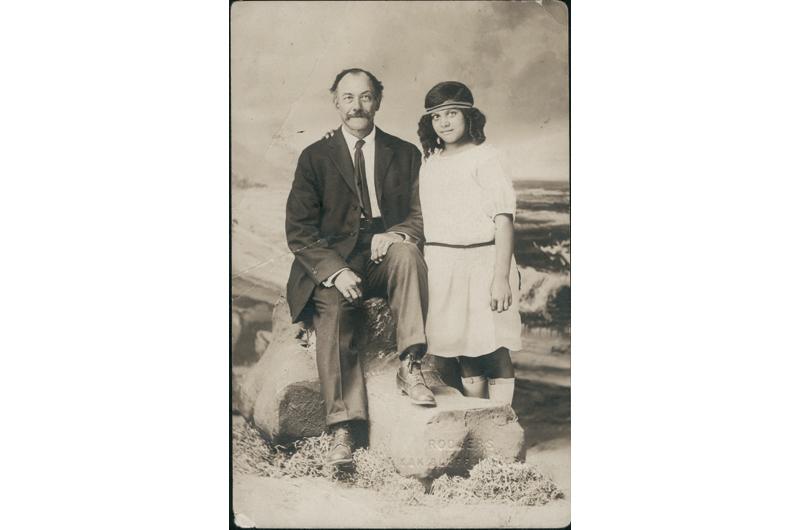

For Penny Gamble-Williams, whose tribal name is Chappaquiddick Woman, the reunion of the Chappaquiddicks was the culmination of her own long journey from Providence, Rhode Island. There, as a young girl, she heard tales of her heritage and of the island of Chappaquiddick and dreamed of the days when her grandfather spent his formative years there with his aunt Sarah, who was the wife of famed black whaling captain William Martin. When Sarah Martin died in 1911, her family’s presence on the island seemed to have died with her.

But Gamble-Williams vividly remembers as a child hearing her elders talk about Chappaquiddick. “We all knew each other,” she explained. “And a lot of times, that would be the topic of discussion. When the adults were talking, they would be talking about the land and how we lost the land.”

Occasionally some of those families even got letters from lawyers about court actions to further partition land on Chappaquiddick that still had their names attached to it. But there was little they could do. “Because we came from hard-working families, no one had the money to hire attorneys and figure this out,” she said.

As a young girl, she would often spend a week or two during the summer in Oak Bluffs with relatives. Each time, a group of them would pile into her Uncle Bub’s Pontiac, board the On Time ferry for the trip across Edgartown harbor, and drive slowly around the island of Chappaquiddick, before crossing the harbor again. “How come we never get out?” she would always ask. But, she said, “No one would ever say anything about it.”

It wasn’t until Gamble-Williams moved away from New England in the 1970s that the grip of her ancestry gained purchase. She was living outside Washington, D.C., and began to follow the American Indian Movement (AIM) and joined the Longest Walk, in which several hundred Native Americans walked across the country to protest the indifference of the government to the plight of Native Americans and were joined by many others for portions of the trip. (Gamble-Williams walked the eight or nine miles from her home in Hyattsville, Maryland, to the Capital Mall.) She became a member of AIM and the Women of All Red Nations.

In the course of her activism, she began to run into members of other New England tribes, including the Narragansetts and the Mashpees. “And so what happened to us?” she’d ask. “What happened to the Chappaquiddicks?”

Over the course of the next two decades, she befriended many from the Mashpee tribe, and came to know John Peters, otherwise known by his Wampanoag name Cjegktoonuppa

(Slow Turtle). Perhaps the best-known Wampanoag of the latter part of the twentieth century, he was not only the supreme medicine man of the Wampanoag nation, but the first executive director of the Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs, a position his son Jim now holds. The elder Peters always offered encouragement when she brought up the Chappaquiddicks.

“If you know something has to happen,” she remembered him telling her, “you’ll find a way to make it happen.”

Visiting the island of Chappaquiddick, Gamble-Williams would walk around Captain Martin’s house, thinking about her great-aunt Sarah and her grandfather, who lived there for a few years. The latter would go on to become the friendly neighborhood mail carrier in Providence, who always carried a pair of moccasins for his sore feet at the end of his route.

Something kept pushing her, and the years of researching her tribe’s roots became a spiritual journey as well as an intellectual one. “This sort of wave was moving me,” she said.

“I wanted to do something for the ancestors. I used to think there were things they wanted to happen, that didn’t happen while they were alive.”

In 1995, after filing for 501(c)3 status, the reconstituted Chappaquiddick Tribe of the Wampanoag Indian Nation held its first annual gathering in the Chappaquiddick Indian Burial Ground overlooking Cape Pogue Pond. There were about fifty people. It was a start.

There was no welcome party to greet a group of Native Americans gathering for – well, for who knows what. It made some residents understandably nervous – perhaps some who feared more litigation over land claims. The skeptics included several well-known and longtime residents of Chappaquiddick who proudly pointed to their Gay Head tribal roots and, said Gamble-Williams, made it clear that they would not be involved with the resurgent Chappaquiddick tribe.

There may have been some tense moments in the early years, said Liz Villard, a Chappaquiddick resident and historian. It may be that most Chappaquiddick landowners were unaware that descendants of the ancient tribe existed. “Ninety percent of us believed the Chappy Indians were extinct,” she said. “I have been coming here since 1949, and that’s what most of us felt.” (As an Edgartown cemetery commissioner, she has helped erect a bronze plaque about the tribe at the Indian Burial Ground and attended annual gatherings there.)

But the Chappaquiddicks received plenty of encouragement from various other Gay Head and Mashpee leaders, and the following year, some of them were in attendance at the second annual gathering. Among them, of course, was Peters, a.k.a. Slow Turtle, whose presence lent prestige to the event, and whose Wampanoag name seems a fitting symbol of not only the pace but determination of the Chappaquiddicks’ journey back.

“I don’t want to use the term validation, but it meant a lot because we knew we were on the right path,” said Gamble-Williams, who to this day remains the tribe’s spiritual leader. “Whatever bumps along the road, it was going to be okay.”

Driving around the island with her car full of relatives, Margaret Gonsalves Oliveira remembered how she found out she was a Chappaquiddick. It was in the 1980s and the Gay Head tribe was in the final stages leading to federal recognition. As part of that process, figuring out exactly who was going to be in the newly official tribe and who was not suddenly became more important.

“My mother was told we were going to be let off the roll because we were Chappy,” Oliveira said. Her younger sister, Yvette, was still in an after-school Indian education class in Gay Head at the time and was also told she wasn’t part of the tribe.

“She was told by an adult, ‘You’re not even Aquinnah Wampanoag; you’re Chappaquiddick, you shouldn’t even be here.’”

It’s obvious there is still some sting to the memory, but Oliveira didn’t sound particularly bitter in recounting it. Bitterness, one senses, is just not in her nature. And besides, she’s as proud now to be a Chappaquiddick as her friends in Aquinnah are to be Aquinnah.

Her feather earrings bouncing as she laughed, she navigated the roads of Chappaquiddick in her Honda Accord, with the Massachusetts license plate NATIV, pointing out various sites. Also in the car were her sister Yvette, cousin Willz (sporting a red sweatshirt and baseball cap with “Chappaquiddick Tribe” on them), and her husband Dave. The trip included stops along North Neck Road, Sampson’s Hill, and the Indian Burial Ground. Throughout the tour the car was full of teasing and laughing – mostly Oliveira’s – the sounds any family might make on a sunny afternoon rattling around the places their grandparents grew up.

Like Gamble-Williams, Oliveira had her own moment overhearing a snippet of conversation among the adults in her household, in this case prompted by a telephone call her mother received. “I just remember her saying to my father, ‘I’ve got six kids and no money. What am I gonna do with land on Chappy?’ And that was it. She was told to consult a lawyer, to get representation. There must have been some kind of court case where her name came up as an heir, and she couldn’t do anything about it.”

In some cases, tribal members never knew they had had slivers of land on Chappaquiddick. Or they knew they did, but never learned it had been legally partitioned. Or they were under the misapprehension that their land was exempt from local property taxes – like true reservation land. Gordon recalled one family that had its land taken by the town in a dispute over $86 in unpaid taxes.

Eventually, Oliveira’s curiosity led her to the annual gatherings on Chappaquiddick where she began to appreciate the kinship, as well as the rites and rituals, especially the cleansing and naming ceremonies. She began talking to her mother about a Native American name, this woman who as a girl was known to her mother as “dogfeet,” never sitting still; who wanted to be a party planner; this oldest among siblings, with fourteen nieces and nephews, who thought nothing of serving meals for two dozen or more, and who leaves leftovers in the mailbox for a cousin.

“You’re in a circle,” she said, describing the naming ceremony. “And you either suggest a name or they give you a name and the person giving the names usually knows something about you. And they said, ‘Is there anyone who has a suggestion for a name?’ And I stood forward and said, ‘My mother suggested my name be Social Butterfly.’

“And they were all just like, ‘Yeah, wooo-woooo!’ They were hooting and hollering,” Oliveira said, flashing her smile. “They got it. They said it was me.”

On a muggy day this past July, about thirty tribe members stood in a circle at the Indian Burial Ground for their annual gathering. Gordon, the sonksq, presided, moccasins on her feet and a leather medicine pouch containing sage and shells hanging around her neck.

For the first time, Oliveira took a primary role in the cleansing ceremony, waving smoke from a smoldering sage bunch up and down the front of each tribal member, and then in the naming ceremony.

As a slight breeze rustled the oak leaves overhead, six members received their native names. As each one was called into the middle of the circle – two young boys, a young man, a middle-aged man and woman, and finally, an infant – the group called out their names three times. Soaring Sparrow, Quiet Wolf, Gliding Falcon, Smiling Bear, Sea Turtle. And finally, Little Robin (ten-month-old Zoe Pelletier from Rhode Island, cradled by her mother).

In the air was a feeling of the changing of the guard as Gordon delivered brief remarks, making note of some tribal elders – including one nearing her one-hundredth birthday – who were too ill to make the trip. There was also a powerful spiritual undercurrent, abetted by the naming and cleansing ceremonies, which ended with a prayer.

A week later, in a phone interview, Gordon suggested that there may indeed be tribal land, some small piece of common land that hadn’t been allotted to families, that might one day be reclaimed by the tribe. But, she said, much more research needed to be done.

“It impacts our sense of tribal identity and our sense of self-esteem that we as a people have a place of our own,” she said.

But on this day, at the annual gathering, tribal members would be content to regroup at the Chappaquiddick Community Center for lunch and conversation. Many proudly wore

bright white T-shirts made for the occasion that read, in part, “We Came Home.”

6 comments

6 comments

Comments (6)