Nearly 150 years ago, soon after the Civil War had run its bloody course, several exclusive striped bass clubs were started along the New England coast, organized by some of the most prominent citizens of the time. One of the most famous was the Squibnocket Club, formed in 1869 on the cliffs of Squibnocket Point in Chilmark. Members were mostly New York business tycoons and also included Secretary of State Elihu Root, while among the visiting anglers were former President Chester Arthur and renowned naturalist Dr. Louis Agassiz. Affairs of state and industry were settled in the clubhouse – libation in hand – after the day’s catch had been weighed, and instructions were dispatched to Washington and Wall Street by the club’s carrier pigeons.

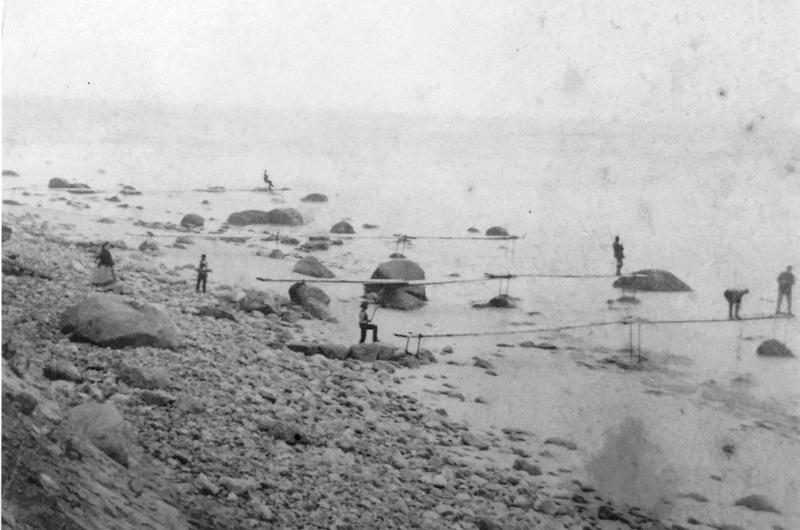

Fishing was done from eight bass stands or piers that ringed the rock-strewn point, each numbered and assigned daily by lottery to one of the anglers, who usually fished in coat and tie, assisted by a chummer, a club employee who was responsible for procuring bait, setting a chum slick, gaffing fish for his client, and otherwise attending to his needs in much the same manner as a mate on a modern-day charter boat. The bait of choice was a chunk of lobster or menhaden.

The clubhouse was a good-sized building near the cliff’s edge with a large living room, many bedrooms, and a porch overlooking the bass stands. Living was far from spartan. The club imported a well-trained manservant from New York to take care of every comfort of its members. Known as Squibnocket Willie, he was said to be such a product of the city that he could not find his way to and from the village of Chilmark without the aid of rocks that were painted white along the way.

What is now called Squibnocket Beach was at that time known as Squibnocket Landing, because before the advent of gasoline engines and before the Army Corps of Engineers dredged and riprapped Menemsha Creek in 1905, the “pocket anchorage” in what was referred to by mariners as Squibnocket Roadstead had for centuries been a major port of entry for Chilmark. Ships regularly offloaded cargos and passengers bound for

up-Island towns, as well as sailors on shore leave headed for the various inns and taverns then on the King’s Highway, an old route that ran from West Tisbury to Quitsa. (Interestingly, before the first bridge was built across the mouth of Stonewall Pond in 1847, the route of the King’s Highway was across the cobbles of Stonewall Beach.)

The early sports on their way to the Squibnocket Club would have passed a beach still lined with dories used by Islanders for the spring and fall codfishing season. Regular barge traffic, carrying mostly sheep and other livestock, between the landing and Noman’s Land would have been ongoing. The remains of the lifesaving station once run by the Massachusetts Humane Society may have been visible at Money Hill, so named for a supposed buried cache of pirate treasure, near where the public parking lot ends today.

A few years after the Squibnocket Club came into existence, the Providence Club was started on the land adjacent to it on the north near the mouth of a man-made herring run that ran from Squibnocket Pond to the sea. As the name implies, the members were from Providence, and they were personal friends of the Squibnocket group. The new club set out three stands of its own, making a total of eleven when added to the original eight that ringed the point.

The clubs flourished for a number of years, and the bass fishing was generally excellent in the beginning. According to the Squibnocket Club’s logs, thirty-six stripers of forty pounds or larger were caught between 1869 and 1880, including a top of fifty-eight pounds landed by J.A. Greene on June 19, 1873. The best year was 1875, with twelve bass over forty pounds, and the best overall month in the club’s history was September, which yielded seventeen of the big stripers.

However, in the 1880s, striped bass went into such a sharp decline that both clubs went out of existence. The Squibnocket Club’s last year was in 1888. In the club’s log, after that date, is inscribed “SIC TRANSIT GLORIA SQUIB.”

The Squibnocket clubhouse survived several fires and, around 1900, was moved by R.W. Crocker to North Tisbury, where part of it was used as a barn and part as a grist mill. Around that time Gardiner Hammond bought the land, resurrected a couple of the stands, and caught a sixty-eight-pound bass from one of them, to my knowledge the largest striper ever recorded at Squibnocket. The hurricane of 1944 closed the herring run, and it was not reopened. Without the attraction of the herring – alewives that were returning to their

natal waters to spawn – bass were simply not vectored to the area in the numbers that had made it so productive in the club’s glory days. Wooden remains of the old herring run have recently been exposed by relentless erosion along the South Shore.

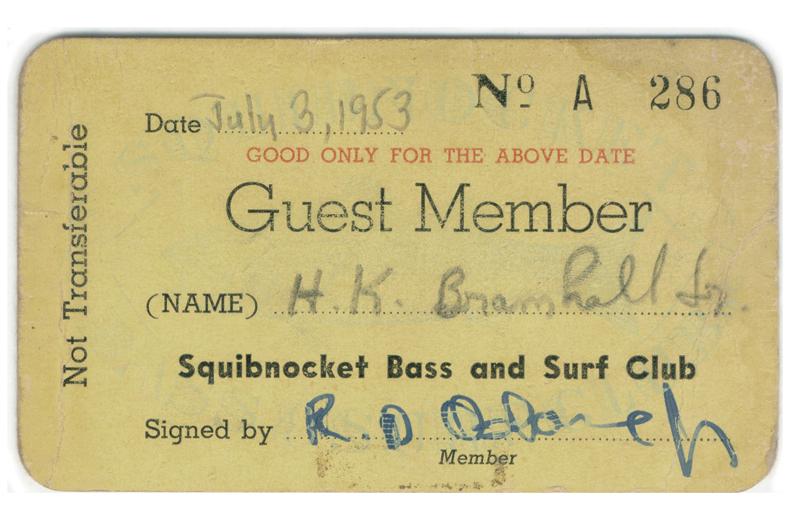

The Hornblower family acquired the property in 1926, and two bass stands were erected again in the early 1950s by the newly created Squibnocket Bass and Surf Club under the guidance of Ralph Hornblower, John Lamborn, and Ralph Osborne, with the work done by Ed Case of Edgartown.

I witnessed Osborne catch a thirty-five-pound bass from the stand at the point one day in July 1953, when I was his guest, and I later caught several smaller stripers from it plus an eleven-pound fluke that hit an Atom swimmer in the middle of the night – not the quarry I was seeking, but nevertheless memorable.

After Hornblower’s death in 1960 the stands were not put up again, but you can sometimes still spot the holes drilled into the rocks and the rusting iron rods that supported wooden piers and formally dressed anglers and their chummers in a bygone era.

The following excerpt was originally published with this article:

Oh Man, You Should Have Been Here Yesteryear...

5 comments

5 comments

Comments (5)