On the porch of the Chilmark Store midday in high season, her name is flying about from mouth to ear, “Did you get your Lucy sticker yet?” “I’ll meet you at Lucy Vincent around two o’clock.” “Looking forward to our picnic tomorrow at Lucy.” Everyone’s thrilled about Lucy Vincent, the beach, the place.

But ask about Lucy Vincent, the person, and you’re likely to draw a blank stare. You may find a few proud former hippies who remember the beach by some of its previous names, but the woman herself? “I never knew there was a person,” said a friend of mine who has lived up-Island for decades. “I just thought it was a cool name.”

Before Lucy Vincent, the person, died in 1970, however, it’s safe to say that virtually everyone in Chilmark knew who she was, even if they didn’t know exactly what to call her.

“When I was a child we called her ‘Cousin,’” said Jane Slater, her closest living relative. Of course they were cousins, but rural America in the mid-twentieth century didn’t allow for familiarity between children and adults, and Lucy, who was the Chilmark librarian, insisted that the children in town call her by her first name, not Mrs. Vincent. This was a problem for many parents who believed it too intimate. Slater had one solution, while Everett Poole (also a distant relative of Vincent) said, “My parents insisted that I address my elders formally. So we got around that by never addressing her directly at all.”

Lucy’s impatience with polite conventions was part of a lifelong pattern, particularly when those conventions involved the prerogatives of women. In her early years, as soon as she could, said Slater, she bought a car, making her the first woman in Chilmark to have an automobile, and only the second person in town to have one. “She was very well-respected in town,” said Poole, “until...”

The “until” moment was when she went to the Chilmark Town Hall to request a shellfish permit and was told that women could not be issued one. Suffice it to say the resulting furor was finally resolved in her favor, and Lucy was one of the first Chilmarkers of her gender to go shellfishing with a permit.

Nor did she slow down. In 1951, at the age of sixty-nine, she reportedly announced she would be selling some properties she owned in California. Her family and friends were concerned about how they would get her out there, but she had already arranged her trip with the Greyhound bus company and had them plot her itinerary. Arthritic and with failing eyesight, she traveled all day, and each evening there was a room reserved by Greyhound for her to spend the night. Of course, she returned, on her own, the same way.

“Remarkable Chilmarker Was a Symbol of Independence,” read the headline of the obituary that ran in the Vineyard Gazette after her death at the age of eighty-seven. “Mrs. Vincent lived alone,” the article went on to say, “insisting that no one could get along with her and she couldn’t get along with anyone. ‘I’m too stubborn,’ she would say, ‘and too independent for anyone else to contend with.’”

Lucinda Poole Mosher was born in Chilmark in 1882 to a family of modest means. Her mother, Marinda Mayhew, had married a field hand who worked on the family farm named Elihu Mosher, of the Chilmark Moshers. At age twenty-two Lucy, in turn, married Myron Vincent, of the up-Island Vincents, who was nineteen years her senior. He was said to be a good investor, and during their decades together they could afford to travel to Florida and the West Coast, where she was a benefactor of the Museum of Natural History in San Diego.

At their home in Chilmark, meanwhile, her interest in birds and flowers complemented his love for the fish that populated the Mill Brook, which ran through the property. He trained them to gather when he rang a bell at their feeding time. They had no children of their own, but between 1924 and 1929 Lucy did her first stint as the town librarian, for a salary of $50 a year, and children were frequent visitors to the house. They were by all accounts happy times, and after Myron died at sixty-seven in 1930, Lucy, then forty-eight years old, lived out her next thirty-nine years alone in the house on the bend in State Road just down-Island of Beetlebung Corner.

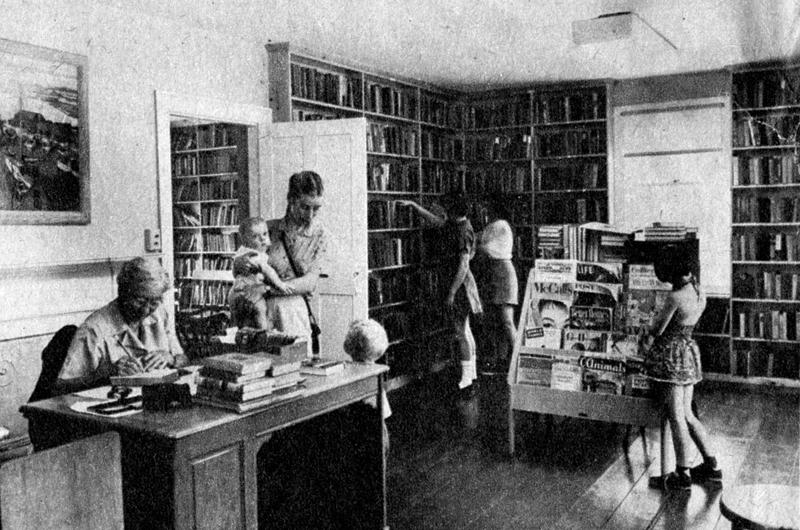

For seventeen of those years, from 1945 to 1962, she again served as the Chilmark librarian. In those days the library, located in the Chilmark Town Hall, was at the center of social life in town. “Yes. Yes, it was the only entertainment in town,” Poole said to Linsey Lee in an interview for the Oral History Archive at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. “I spent a lot of time at the library. It’s funny. It stayed open Saturday night, you know. Which nobody would think of going to the library on a Saturday night now…Oh, I never missed a week at the library during the wintertime. Never went in the summertime.”

Lucy was by many accounts an exemplary librarian, who paid special attention to the children, always willing to guide and assist, and was considered generous with her knowledge. The visits from young people to her home also continued, and she kept up her late husband’s tradition of ringing the bell for the fish as an amusement. Slater remembers the house as “having collections of things; it was like a museum. She would lead us kids around the house pointing out special objects and giving their story.”

As her years in the public eye accumulated, so did her influence. “Lucy Vincent was one of the leading people in Chilmark,” the writer and musician Gale Huntington told the oral history archive in another of Lee’s interviews. “And if some question was going to come up in town meeting they said, ‘Well, you better go and speak to Lucy about that.’”

People in the public eye, however exemplary, can become targets, and somewhere along the line a story has erroneously attached itself to her name that goes something like this: “Oh, I heard that when she was the librarian in Chilmark, if any salacious book came in she would go through it and tear out the offending pages.” A general query online about Vincent will also turn up the malicious librarian ripping pages out of books.

“No, that’s not it,” said Poole. “She had a drawer in her desk, and she’d put the book in there.” Slater agreed: “Lady Chatterley’s Lover was on the bookshelves. I know, because we kids used to sneak it off the shelves and quickly read what we could,” indicating that for a book to go into Lucy’s drawer it had to be quite salacious.

One day in her early teens, Slater was walking in Menemsha and an “old duffer” spotted the novel All the King’s Men under her arm. He called out. “You’re too young to have that book, young lady.” Slater walked on. At the library, she was told that the “old duffer” had come in and complained about Slater having an adult book. Lucy’s solution? She told her, “From now on you can sign your mother’s name when you take out books of that kind.”

“A myth,” said David Seward about the censorship story. Seward’s mother was a close friend of Lucy’s and he knew her well himself. As evidence he offered a story about her neighbors: “The blue mailbox belonged to the Barn House people. Lucy allowed them to use her beach. When told the people were nude much of the time, she responded by saying she never checked on them and could care less as long as she didn’t have to view them. Lucy was not a prude.”

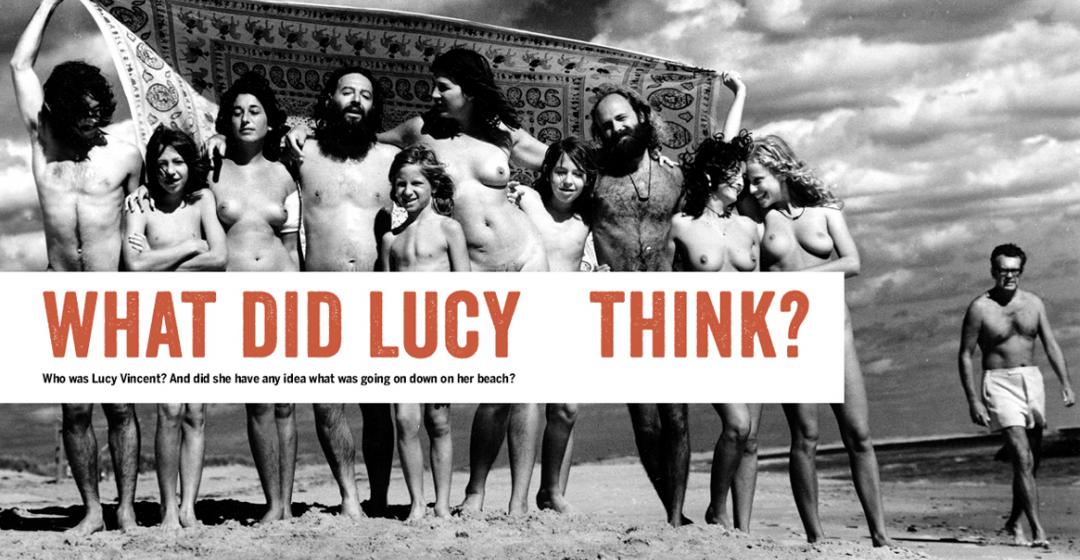

Nudity: with the possible exception in recent years of erosion, it’s probably the thing for which Lucy Vincent Beach is best known. Most any beach on Martha’s Vineyard can be a nude beach – if you go far enough to the left or right. But the magnet distinction of being known as a nude beach reached a pinnacle in the late 1960s and early ’70s with Jungle Beach, as Lucy Vincent Beach was known at the time.

Before that it was known as Barn House Beach or Blue Mailbox Beach. Located just up-Island of the Allen Farm entrance off State Road, Barn House was an artsy, intellectual commune that was formed in 1919 by a group of friends. It hosted many writers, artists, and activists, such as Sylvia Plath and American Civil Liberties Union founder Roger Baldwin. Thomas Hart Benton and Max Eastman would dine there, and various of them would bathe in their birthday suits. Barn House is now part of the National Register of Historic Places.

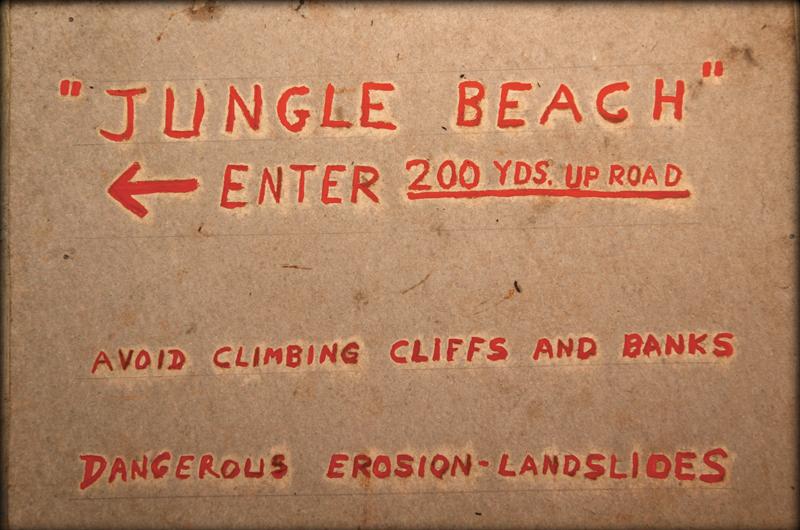

“We grew up in Lambert’s Cove in the ’50s, and were frequent visitors to Barn House Beach, as it was then known,” said Albie Scott. “We used to park in the field next to the stone wall, walk across the field, and wade through the bog between field and beach. As the beach became more popular in the late ’50s, people started calling it Blue Mailbox Beach, as the Barn House community had a blue mailbox. With more people using the beach, the field was closed to parking and we used to park on the road shoulder. At some time in the ’60s, a plank path was put in across the swamp. At the end of the ’60s the wild and hippy youth discovered the beach, and it was dubbed Jungle Beach.”

“The name stemmed from the walk from the road to the beach,” remembered Skip Finley. “After crossing a plank over the small stream, the vegetation of the meandering path

blocked the sky for much of the way. Hot inside along the trail, the wind at the end was wonderful. The beach was decorated with handmade statuettes of clay; once a Mayan mask in the cliffs, another time The Thinker perched on a boulder. [You] parked the car at the Chilmark Center and hitched to the ‘opening in the woods’ or locked your bikes to the steel protective fence. Then one day some genius drove six bulldozers side by side to the beach and destroyed the jungle...yay. Today, although unpaved, a parking lot.”

(Having experienced the Jungle Beach path back in the day myself, I believe the source of the name is one plant that dominated that area and can still be seen on the side of the road just down-Island of Lucy Vincent Beach. It was sumac that gave the walk a jungle flavor.)

Not many people bothered to ask the old woman who lived in the house near the head of the path if she minded them crossing her property and using her beach, but Eric Ropke did: “Must’ve been 1969,” he recalled. “I was living down-Island at Peace Gate. Some friends said, ‘You have to go to Jungle Beach.’ So we go up to this house in Chilmark and they start running through the yard past it, so I do too.

“Next time, coming by myself, I thought that running thing just hadn’t felt right. I saw an old woman looking out the door of the house, so I walked right over and said, ‘Excuse me, ma’am, I know an awful lot of people just pass right by your house and go down to the beach, and I decided to take a chance and ask for your permission.’ She paused for a moment and looked me over.

“Now you have to understand, my hair was long and I had a sort of sideburn/Fu Manchu mustache combo, a tank T-shirt, and a leather loincloth. That was it. She said, ‘Young man, you are the first one to even bother to ask, and because you came and asked me directly, anytime you see me standing in the door just wave and I’ll know that it’s you. You have my permission.’ So sometimes it pays to take a chance like that.”

What Ropke didn’t know was that Lucy by that time could barely see, which may have in part explained her blasé response to his garb. But given her libertine nature, she likely would have given permission even if she had a clear-eyed view of his sartorial choice of a loincloth.

Ropke was part of a wild anarchical invasion of longhaired folks who had no knowledge of who owned what, and who felt that beaches were and should be free. The generation of beach seekers (nude and otherwise) just before, in the Blue Mailbox era, had a vastly different approach to the problem of beach access over land you do not own on your way to a private beach you do not own. “Every year a delegation from Barn House would go to have tea with Miss Lucy,” Tip Kenyon told Lee for the museum’s oral history archive:

“And then in due course, after saying ‘Hello,’ and ‘How are you?’ the subject of the beach would come up. And she just – she wanted certain standards observed, and she always made it known. I never went to one of these; I just heard about them, but I remember that was always early, maybe in March. They would come up and have their tea with Miss Lucy. And she would always say, ‘Well, of course you’re welcome to enjoy the beach again this year.’”

The polite socialists and communists of the Barn House also had an arrangement with Roger Allen of the Allen Farm, and each year renewed their permission to cross his field. Kenyon again: “Roger [Allen] had cows that were right up to the – when we walked through the meadow, there were frequently cows out there, and then when we got through the bog and started up the hill to the top of the cliffs, where we looked out at the ocean, there were cows over there, right at the top of the cliffs. I mean, sometimes you’d be down on the beach and there’d be a cow looking at you.”

It was an age before cell phones and social media, of course, but eventually word got out. “And this beach got a reputation up and down the eastern seaboard and beyond as a wild place where you could smoke pot and go nude and so on,” Ralph Brown told Lee. “And then Roger Allen’s widow was making an almost futile attempt to keep people off because you really had to cross, didn’t have to, but the best way to get there was across her field, and she wanted the Chilmark police to stop it…There came a time when they wanted to know, could they park a couple of their cruisers here in our parking place, right here by the side of the house [at Barn House], from which to sort of… keep an eye on trespassers. And we’d want to be on the good side of the Chilmark Police and we said, ‘Oh, yes indeed.’ When our children found out about it, they were teenagers at that time, not just our children but all the children, they raised almighty hell. And they said, ‘You’re cooperating with the fuzz.’ And so we had to withdraw the permission.… Oh, it was a mess and…we weren’t suppose to go over there anymore. We learned various circuitous ways of getting to the beach, which we would use. Plowing through woods and stuff.”

In 1968, when David Seward was twenty-one with a young family, he got a phone call from his mother’s friend Lucy. She offered him $2 an hour (minimum wage then was $1.60 an hour) to help out twice a day, seven o’clock in the morning and five o’clock in the afternoon. She made it clear that because of her near-total blindness, without his help she would not be able to stay on her own in the house, and she was determined to stay there alone as she had for more than thirty years.

Seward was working hard at the time to support his young family, but he had enough work at the moment and felt uneasy about the idea of assisting an elderly woman. He demurred. She, however, persisted, and as she was trying to persuade him, he heard the phone drop to the floor and her heavy breathing as she sightlessly groped on the floor for the errant phone. When she finally found it and brought it to her ear, his heart had been softened by her distress and he said he would take the job. After that, twice a day, every day for two years, he was there helping, and that allowed her to retain her style of independent living until her health failed.

To the end, she was the thrifty, practical woman she had always been. One time, he was at her house doing his chores and she asked him to get a bank book from her desk – the “old bank book,” she said. Her father had opened an account for her as a child, into which she had put $5 every week. To his surprise Seward saw that there was more than $80,000 in the account; all those deposits over eight decades had added up, and there had never been a withdrawal.

Another day he came over as usual and she asked him to check on the big rock out off the bluffs of her beach property, the one with the hole in it. Once on the bluffs, he used binoculars and saw the rock out in the water. Back at the house she asked where it was in relation to the shore and when he reported it was about 300 feet out she said, “Call the assessor,” not wanting to be taxed on land she owned that had eroded away.

In her last two years at home, Seward filled Lucy’s bird feeders morning and night. Every Thursday she would ride with him to go shopping. First stop was the stone bank in Vineyard Haven. Her attorney had arranged that a teller at the bank would hand Seward $50 from her account, and he would go across Main Street to (in its original location) Cronig’s Market, where, along with Lucy’s personal needs, he would purchase two big jars of peanut butter and suet from the butcher. Those weekly supplies, plus the fifty-five-gallon drum of sunflower seeds that Seward kept filled, insured that on her property there were no empty bird bellies.

Her second passion was for her gardens, both for flowers and food. Daffodils in great profusion would announce spring. Late one afternoon, not long before she entered the hospital for her last stay, she was found on her knees in the flower bed. That morning she had felt an urge to get close to the earth, but her poor eyesight had prevented her from getting back into the house. She had not had any food since breakfast. When found at dusk, she was tired but not frightened, having spent her day in the garden.

When Lucy died in 1970, so too did the polite afternoon visits from Barn House progressives for tea and permission, and in the three-year period before the town opened Lucinda Vincent Memorial Beach for residents, everyone, longhaired and crew-cut alike, was scrambling to get to the ocean by any means necessary (i.e., trespassing).

Bill Vincent, Lucy’s nephew, remembers that while at the house in the early ’70s, he would be in back mowing their path to the beach with a noisy power mower, a three-day job, and people would be walking or running by and saying, “Good work!” “Nice path!” thinking he was doing it for them. His mother, Natalie, would be out sunbathing in the yard and the youthful, tanned, happy trespassers would be going by. “People would be climbing over the gate and running,” he said. “Jungle Beach really exploded after she died in 1970.”

“Twenty-five people were a crowd in 1969,” said Ropke. In the early 1970s, on the other hand, “I was walking in on the Jungle Beach path and there’s a fat guy wearing a Santa Claus hat and a red jock with jingle bells on it. He’s stomping around going, ‘Ho Ho Ho.’ At the beach there were 200 people; there were lawn chairs. So I left feeling, we’ve lost it!”

Lucy owned sixty acres that dip and roll in a pleasing fashion around her old house. The land extended over a knoll to the cliff edge above the 4,400 feet of shoreline she also owned. In her will she left the property to her nephew Bob Vincent, Bill Vincent’s late brother, thinking that since he lived off-Island he would likely need to sell it. But he decided to keep the house and some surrounding land, and with Bill’s help it has been kept up, primarily as a summer rental.

Though Lucy’s will contained no reference to the Town of Chilmark acquiring beach property, she had spoken of her desire that part of her property might be used as a town beach. At the suggestion of her executor, Leslie Flanders, her heirs gave the town the right of first refusal in any sale for a price to be determined by the average of three appraisals. According to reports in the Vineyard Gazette at the time, when the resulting price of $450,000 “proved fantastically high, Chilmark selectmen began seeking prospective buyers who might be able to purchase the property, but would allow the town to have access through their land and would give the town the beach.”

After two years of negotiations, in a complicated transaction, a consortium of buyers ended up with forty acres and 1,900 feet of the beach, and the town took control of nearly fourteen acres with 2,500 feet of ocean frontage. Technically, the property is the town’s to use and maintain based on a ninety-nine-year lease that is renewable for an additional ninety-nine years, until 2170, which could be the occasion for a Jungle Beach bicentennial party. Perhaps ironically, given the beach’s hippy reputation, one of four private purchasers behind the deal was Robert McNamara, then president of the World Bank, and for some an arch-villain of the Vietnam War. The home McNamara built was later sold to John Belushi.

It has been forty-seven years since Lucinda Poole Mosher Vincent died, and forty-four years that Chilmarkers have been legally enjoying the beach she once owned. So it’s understandable, perhaps, that the distinction between the person and the beach has been lost. But now that you have been empowered with the facts, if on the porch of the Chilmark Store you hear Lucy Vincent’s virtues being crowed about, you can silently add the word “beach” after her name, and perhaps raise your glass of lemonade in honor of one independent woman’s generosity.

31 comments

31 comments

Comments (31)

Pages