Captain Bob Douglas and his wife Charlene didn’t open The Black Dog Tavern nearly half a century ago thinking about related merchandise, online sales, or the twenty-six stores that now dot the Eastern shoreline from Maine to Florida. They opened their tavern on Vineyard Haven harbor on New Year’s Day 1971 because they wanted a quality, year-round restaurant. The statue out front that pays a lifelike tribute to the Douglas’s Labrador at the time, also named Black Dog, didn’t turn into coffee cups or sweatshirts for another decade or so.

“Someone said one day, ‘Where are your T-shirts?’” Captain Douglas remembered recently. “And I said, ‘I run a restaurant, not a T-shirt shop.’ And they said, ‘No, you’ve got to have a T-shirt.’”

That was around 1980, and he estimates they now sell about 250,000 shirts every year. And of course, T-shirts only marked the beginning of what became Black Dog nation, just as it may have unintentionally launched the rise of the Vineyard as a branding behemoth. These days, it seems, every season brings a new Island-themed brand or logo.

Many of us – more likely, every single one of us – have bought a product at one time or another that we identify with a place. And in this instance, the place we’re talking about is Martha’s Vineyard.

But what is it, exactly, that’s being sold? Perhaps it’s part function and part emotion. Maybe it’s a T-shirt. Or it could be a coffee mug, a dog collar, a tie, or even a license plate. These days, it could even be a beer, a bike, a candy bar, a picnic basket, a pair of sunglasses, or a $300 haute couture men’s bathing suit. To the owner, the object conjures up a particular image, identity, or memory of the Vineyard. But maybe, just as important, it broadcasts to the immediate world around us, “I’m from Martha’s Vineyard. That’s my place.”

This tendency of both residents and visitors to identify with the Island was clear when the Martha’s Vineyard Museum created a new logo last year. “It was amazing because in all the research we did at the museum over the last year, there was such a pride of place that came up,” said Stever Aubrey, the chair of the museum’s board and a successful marketing and advertising executive who was initially opposed to using the geographical image of the Island for the new logo. “It can be very different for someone who grew up here, or the person who’s a tourist and spends a day, or the homeowner who’s here because this is his refuge. But that iconic outline of the Island says something to all of them.

“I think what you find here is what you’ll find in other places where people go for refuge and to retreat,” he continued. “There’s this pride of place and a sense of belonging that has to do with the place itself and seems pretty unique to islands. Nantucket has it, so does Fisher’s Island off the coast of Connecticut.”

Gail Schoenbrunn, a creative director at the Boathouse Group, an advertising and marketing firm in Boston, believes much of the pull toward a regional brand identity is a response to an increasingly globalized world. “Sense of place is not new,” she said. “The rain that falls, the soil that nurtures, the sun that shines produces the only grape that can be called Champagne. Sense of place has always been powerful. In today’s moveable feast, it is often expressed in what you wear or what you drink.”

Take, for example, Nantucket Nectars. Founded in 1989 by Tom Scott and Tom First, Ocean Spray bought an 80 percent share in 1997, then in 2002 Cadbury Schwepps swooped in. Today, the brand associated with our sister island is owned by the Dr. Pepper Snapple Group, based in Texas. One assumes most people think they’re taking a swig from Nantucket when, in fact, they’re sloshing down a drink from the heart of Bush country.

“In one way, it is tribalism writ large,” Schoenbrunn added. “In another it goes beyond the sense of belonging to a statement of what you, the individual, stand for. It is ultimately what defines the brand of you. That personal connection is what gives a brand based in place its power.”

A personal connection to the Island is one thing, but can it explain a quarter of a million T-shirts a year, many of them sold in stores that are hundreds of miles away? The allure of the larger Vineyard-themed brands, it would seem, must include a connection to a place and a set of qualities that the owner aspires to experience or attain even when there is no genuine connection to the place.

“What makes a brand successful in many instances is that people identify it with a particular region or sense of place,” said Ben Scott of Bluerock Design. Though based on the Island, Scott and his wife and business partner Lainey Fink, run a “comprehensive branding firm” that serves mainstream, mainland businesses as well as Island-based endeavors, such as Norton Point, which makes eyewear and accessories from reclaimed and recycled plastic from Haiti. “A sense of place is a grounding,” he added. “And it can become a way for people to assimilate with a brand without ever visiting there.”

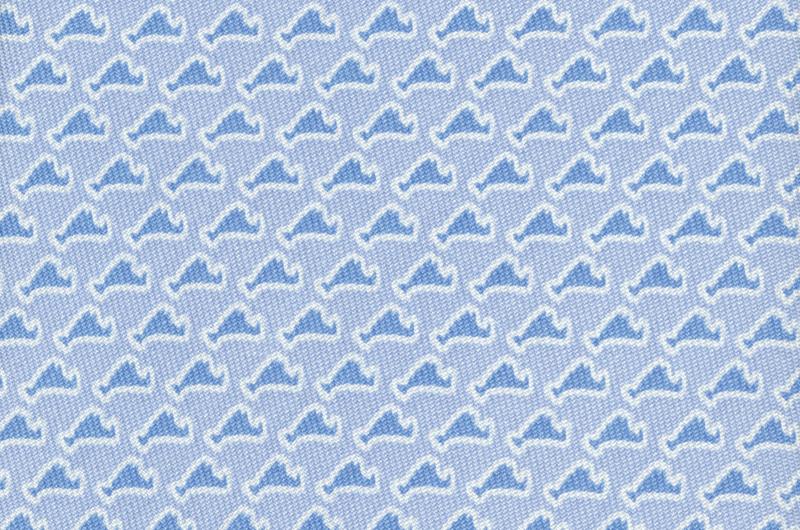

More to the point, from the modern marketer’s perspective, transcending any “authentic” connection to the Island is the true measure of big-time success. Take the giant Vineyard Vines. Launched by brothers Shep and Ian Murray with a line of neckties that showcased Vineyard street signs in July 1998, today there are more than ninety stores, thousands of employees, and a Stamford, Connecticut, headquarters that Bloomberg.com called “the preppiest office in America.” Reuters reported last year that a possible Goldman Sachs deal to sell a minority stake could make it a billion-dollar operation.

So whether or not you think the Vineyard is the preppiest island in America (say it isn’t so, or at least not yet), the version of the Vineyard the Murray brothers are peddling is clearly resonating even among far-flung consumers who are likely never to set a sockless topsider on our shores. The company did not return our calls, but there are YouTube videos aplenty about this hugely profitable clothing line that defines itself as a “lifestyle brand, not a fashion brand.” The smiling pink whale is ever present, and then there’s the company motto: “Every day should feel this good.”

Who can argue? Jill Avery, senior lecturer at the Harvard Business School, puts the Island in the same branding camp as Nantucket, the Hamptons, and Chatham, and said Vineyard Vines’ prominent symbols of lobsters, fishhooks, anchors, beach chairs, and golf balls evoke “the New England preppy summer.” It’s about summer “and all of the good things that go along with it, such as sunshine, ocean, beaches, relaxation, casualness, and vacation. Summer evokes very positive emotions in consumers.”

As does, it might be argued, the association of the style with a certain affluent lifestyle. “Their shirts, pants, and other clothing items mimic the traditional summer wardrobes of New England preppies,” said Avery. “Their goods are sold to New England preppies, but also to many other consumers who aspire to be New England preppies, even those consumers who have never visited the Vineyard, but who yearn for the romantic image it portrays.”

In contrast to the somewhat accidental origins of the Black Dog, Vineyard Vines was clearly a deliberate branding choice. So too was new “lifestyle” company Chappy Happy (tagline: “Let life smile.”) And Bad Martha beer. “When I thought about creating a beer company as something to do in retirement, I thought conceptually of Bad Martha and created the entire positioning for the brand here and nationally, and then I hired a brewer,” said Jonathan Blum who co-owns Bad Martha with Peter Rosbeck Jr., a local builder and developer.

Blum, who remembers spotting a Black Dog T-shirt while touring the Great Wall of China twenty years ago, moved to the Island full time with his family three years ago. Before “retiring,” he spent his career in brand marketing, first with the international advertising firm Ogilvy & Mather Public Affairs, then PepsiCo, and finally YUM brands (aka Pizza Hut, KFC, Taco Bell). “I wanted to do something that paid homage to the Island, but something that had not been done before,” he said.

The result was Bad Martha, an unusual amalgam of a craft brewery and an aspiring regional brand. Most of the beer is brewed and bottled off-Island at a contract brewery in Ipswich, Massachusetts, and is sold at more than five hundred locations around New England. Between May and October, however, the company also brews and serves a rotating collection of small-batch recipes on tap at its post-and-beam “Farmer’s Brewery” overlooking Donaroma’s nursery in Edgartown. The brand touts the fact that they include grape leaves from the Vineyard in their recipe, and that their craft brews use a variety of other local ingredients for flavor. The business plan includes eventually opening similar farm-themed microbreweries off-Island.

As for selling products linked to the Vineyard, Blum said “it appeals to people who have been here or want to be here. That’s what all of us who have created brands that have gone to the mainland achieve, that’s what we’ve done. We’re looking to capture the imagination of either people who want a bit of the Island all year round or people who would like to go there and capture its beauty.”

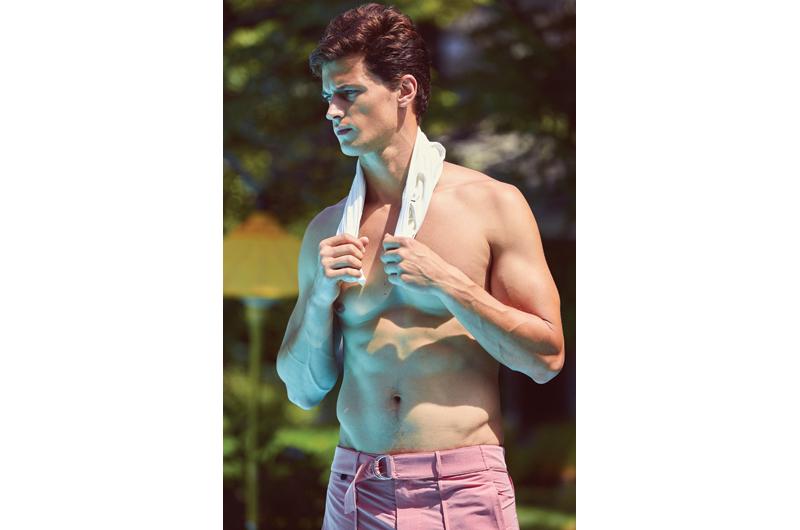

There’s a wink and nod to the Vineyard to be found in another relative newcomer, Katama, an upscale line of men’s casual clothing and swimwear. The company was founded in 2015 by Garrett Neff, a top male model who wanted to pay homage to a decade-plus of Vineyard summers beginning in the mid-eighties. “After all the travel and being in the air and staying in nice hotels, I really began to grow nostalgic for those simpler times and activities that I remember as a kid with my family. For me, the brand is about reconnecting with the outdoors, the crab fishing, canoeing – simple activities that anyone can access and appreciate.”

Neff refers to the brand as Kah-tah-mah, which is closer to the original Wampanoag pronunciation, when it conveyed a crab-fishing place. And though he made his modeling career with some of the biggest logos in men’s clothing, he wanted Katama to be largely logo free. It seems to be clicking. Katama clothing can be found online and in high-end retailers in Japan, New York City, Montauk, New York, and Provincetown. At press time, Neff was still looking for a retailer on-Island.

“I wanted to pay respect to the origin of the name, but it also ties back to the simple activities I’m nostalgic for,” Neff explained. “The idea is almost anywhere you bring your Katama products, you are set up to have an authentic outdoor experience.”

Authenticity is a notion that comes up frequently in conversations about branding. To Rob Douglas, the general manager of the Black Dog and one of four Douglas sons who are involved to varying degrees with the family business, the brand’s success is attributable to the company’s ability to stay true to his father’s initial motivations.

“There was never a meeting or a decision to launch a brand,” he said. “The success of the brand came from the good decision my father made in 1970 and he has steered the brand to stay true to his vision, which has really been about Martha’s Vineyard, the waterfront, and quality, whether it’s food or the products we make.”

According to Harvard’s Avery, “Place branding is a form of co-branding – combining two brands together to leverage the brand associations of one for the benefit of the other.” But, she added, “The ‘story’ behind the product matters as much as the product – where it is made, how it is made, and its connection to the place that inspires it. Companies that are perceived to be inauthentic or illegitimate risk losing their association with the place.”

Can the branding itself lead to a dangerous tipping point, a grumpy, cantankerous Vineyarder might ask, when the Island loses the very authenticity everyone else is trying to market?

One more semi-accidental Island brand to consider: street signs on neckties may have paved the way for the Vineyard Vines empire, but they were pioneered as an Island totem by the late jewelry designer Cheryl “CB” Stark. The signature bracelet charms she created replicating each of the six town signs proved to be an important differentiator for the store, which first opened in 1966, four years before the Black Dog Tavern. As Stark’s widow and business partner Margery Meltzer recalled, “One day Cheryl said, ‘I have it. We’ll do the town signs.’ And I said, ‘What?’ and she said, ‘We’ll do the signs,’ and we started making them and people started wearing them all across the country.”

The charms, said Meltzer, were the bread and butter for the store in the early days. “It was really taking something that’s apparent or obvious in the landscape and translating it into a piece of jewelry.”

The distinction, Sarah York, the store’s manager for the past fifteen years noted, is “it has to be authentic. You can’t just walk in here and put an Island on something and expect it to be the next big thing. I’ve seen it crash and burn a number of times.”

So what are the authentic and obvious features of the Vineyard landscape today? You guessed it. Among the classic charms now available from CB Stark are a 14-carat gold Black Dog T-shirt and a pink enamel Vineyard Vines whale.