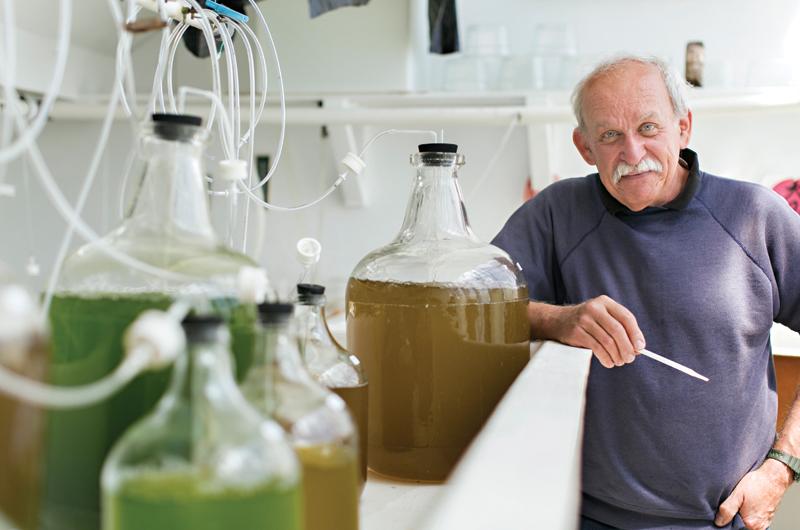

Rick Karney turned sixty-six years old in December and told the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group, which he has led for more than forty years, that it was time to pull back, pass the baton of leadership, and pursue his other passions, such as gardening. This amiable man with the thick, dipping mustache that fails to hide both smile and twinkle has not so much walked away as redirected some of his prodigious energy.

First, he’ll admit, he’ll probably keep working half time. What’s more, one of his coworkers, Emma Green-Beach, is expecting a baby this spring, so he’ll return full time for a while. And then, in a rambling conversation, he’ll add that maybe there will be a small project or two the shellfish group can get funded that he’ll run on the side. In other words, there’s no rocker on this porch.

Over the decades, in conjunction with the Martha’s Vineyard Commission and others, Karney’s work with shellfish seed production and innovation led to the unmistakable conclusion that nitrogen was clogging and poisoning our ponds. The shellfish group’s educational efforts around oyster agriculture led to a new crop of oyster farmers on some of those same ponds. Their bread and butter – bay scallop culturing – has created methods that have been accepted and copied as state of the art across the region. As for numbers: 30 million shellfish seeds were released last year and a little more than half a billion since 1976.

So, it was time, we thought, to put some questions to Karney – some that look back, some ahead, and some straight in the mirror.

How did a kid from inland New Jersey end up in a hatchery on the Lagoon?

My parents had a little boat and we would go to the Jersey shore a lot and I was exposed to marine life, for sure. I got a degree in general biology at Rutgers and was thinking about grad school, but ended up taking a job at a field station in Virginia. That’s the first place I saw a live scallop. We were doing, really, the first work in shellfish hatchery, but after three-and-a-half years, I was looking for a change. I came up here for a job interview with Mike Wild [at the Martha’s Vineyard Commission]. I had never stepped foot on the Island.

That first winter [1976 –1977] they were air-lifting food to Nantucket because of the ice and I was caretaking one of those three-quarter houses in Edgartown with electric heat and I was cold and miserable. But then a grant came through, and by 1979 to 1980 the hatchery got funded and I thought, ‘I guess I’m committed for a while.’ You think you have some control over your life, and then it’s just how things turn out.

What’s led to your success?

In a lot of ways, we’ve been successful because we’ve been lean and mean. If we had been fully funded, we probably would have kept doing the same thing with enhancement and production of shellfish seed. But because we never had enough money, we went after grant money, and that usually means cutting-edge stuff. It made us reach out and stay relevant and current, because we could never sit back and be fat and happy.

And your biggest setback or disappointment?

Mostly when we had something that didn’t work, it was because the funding wasn’t there. Still, I wish we had been more successful in dealing with water-quality issues – it’s a constant battle. The fisheries have still declined over the years despite our efforts, but it could have been worse. Still, if you don’t have good water quality, it doesn’t matter how much we produce.

What about those big issues – water quality, climate change? Are you an optimist or pessimist?

I’m an eternal optimist. I grew up in New Jersey before the EPA and the Clean Water Act. And I lived next door to a chemical factory, which became a Superfund site. When I see the Vineyard and how really good we have it here, I think back about what we lost in New Jersey and it kind of motivates me. We can’t ever throw up our arms. There’s a dark cloud over the environment now, but I would hope it’s just a passing thing. I just can’t imagine people want to go back to those dark times.

What’s your favorite shellfish?

I guess scallops. They’re all great, but the scallops are more animated and they’re fun to work with. Something about the scallops and the eyes and the clapping.

I meant to eat.

Oh. I’ve been eating a lot of oysters because of all the nuances with all the different kinds. They’re all a little different depending on where they’ve been, whereas all bay scallops taste the same, which is fantastic. But I can eat a lot of different kinds of oysters and have a lot of different experiences.

And can we talk about the mustache? Have you always had it?

Pretty much since college. It’s funny. I was approached once to raise money for a student endowment fund for the National Shellfish Association and they asked me if I would shave my mustache, and I said, ‘No, I don’t think I can.’ I’ll trim it and think I should shave it off, but I don’t. You get locked into your own space and time and it’s your identity.

Which went white first?

I used to be dirty blonde. I think it all went white at the same time, but at least when the hair on your head starts falling out, you still have your mustache. And I don’t mind the change in color.

You haven’t really retired, have you?

I don’t think it’s healthy to completely step away. But when you get older, you have to make way for younger people. I have younger coworkers and they’re just as passionate as I’ve been and I feel like it’s good, I can pass the baby on.