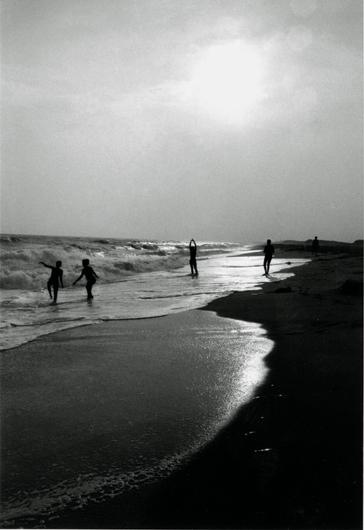

With the crowds of Circuit Avenue behind me, I headed out of town on a summer night down Beach Road. The overflow bar-goers and the boom of the last song faded away to crickets in the grass and the occasional whoosh of a car passing by. I pulled over on State Beach, towel in hand, and darted for the shoreline. The only remedy for a hot summer night was a dip. A sky full of stars and little moonshine meant it was an optimal night for a different kind of light show: bioluminescence.

I was introduced to the phenomenon not nearly long enough ago. Swimming in a sea of bioluminescence is like a good restaurant you discover at the end of a trip; you wish you had found it sooner so you could have gone back.

It’s easy for your mind to wander toward Jaws when swimming on your own at night,

especially on State Beach. But with the company of the plankton lighting up as you swim along shallow waters, like fireflies dancing right beside you, fear subsides and you get to be a kid again. Splashing and kicking around the water is encouraged; laughter is a given.

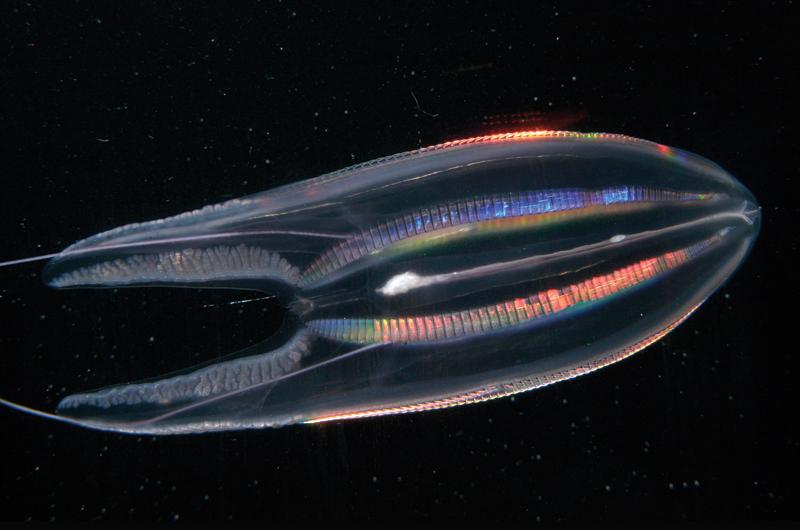

Bioluminescence is sometimes mistakenly referred to as phosphorescence, but the two are not the same. Phosphorescent organisms, including some faintly glowing lichens that can be found on dark nights on the Vineyard, absorb light from the sun and later give it back. Luminescent organisms, on the other hand, actually produce light through a chemical reaction. The bays of Vieques in Puerto Rico are famous for their light shows, as are beaches in southern California, and Toyama Bay in Japan, where “firefly squid” can line the shoreline. But bioluminescent plankton also live in Vineyard waters, and can shine nearly as brightly.

When you bring up bioluminescence to fishermen, the crisis of fisheries and the good old days of Menemsha fade away and it’s as though they remember for a second why the sea called them in the first place.

“If you’ve ever been out on a boat at night, you can’t miss it,” said Hutch Kirwin, who was dropping off steamers one morning at Menemsha Fish House. “It’s always in the wake at night. It’s phytoplankton, so it’s a cool thing because you know it’s animal life. Depending on where you drive [the boat], it gets dark or lighter, and sometimes you see it really vividly.

“If you’re fishing at night,” he went on, “and your line is going back and forth through the water, when the fish gets up near the boat you can see the luminescence on the fish really easily.”

Stanley Larsen, meanwhile, remembered a particularly bright night off of Nomans Land. “The lights were all lit up around the boat. I didn’t even have to use a flashlight or anything it was so bright,” he said. “I remember seeing this big, long line heading right toward my hook. It was kinda going along and bit my hook. It turned out to be a really big congrio.”

The most common bioluminescent plankton in local waters are from the family of single-celled organisms known as dinoflagellates, and they light up due to a similar but not identical chemical process as fireflies. (An unrelated aside: eastern Massachusetts, including the Vineyard, is a linguistic pocket of people who prefer to say “firefly” surrounded by a sea of people who interchange “lightning bug” and “firefly.”) In both cases, the light is produced by the oxidation of compounds known as luciferins, and in the plankton the process is often set off by agitation of the water. Some bioluminescent species will stay lit up for several minutes or more. Others, including most of the local bioluminescent planktons, flash brightly instantly and that’s it.

“When it starts coming in, it just gets thicker and thicker,” said Mitch Pachico one morning as he, too, was bringing in a load of steamers to the Menemsha Fish House. “It doesn’t stay around for long. One night I was down in Tashmoo Pond a couple years ago and I swear to God it was so thick it was like paint; you kicked the water and it would just go up on the beach.”

Pachico tried to take a video with his phone, but alas, the organisms refused to appear on the small screen. “People would think I’m lying,” he said.

In Vineyard waters, bioluminescence is largely seen in plankton and comb jellies, but a surprisingly large percentage of marine animals emit some light, including many sea cucumbers, jellyfish, and fish. By some estimates upwards of fifty percent of deep ocean species may be bioluminescent.

Organisms luminesce for various reasons. They use it to stand boldly against predators or to entice a mate. A particular favorite of Paul Fucile, a senior engineer in physical oceanography at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), is a camouflage technique called “counterillumination,” which starts with a familiar ocean scenario: big hungry fish down below, small tasty fish up above. “You have a fish who doesn’t want to be eaten, so he receives light at the top of the water and re-emits the same frequency and intensity of light from below,” he explained. “Fish that lay in the depths looking straight up are looking for shadows of fish and go up and eat them. Because these fish counterilluminate themselves, they aren’t seen and aren’t eaten.”

Though associated with drifting, some dinoflagellates are capable of propelling themselves up and down in the water column, often on a daily basis. Others can be “trained” in a classroom through the use of artificial cycles of light and darkness to light up during the daylight hours. “Do they have an internal clock?” Fucile asked rhetorically from his office at WHOI. “Do they know when the sun is going to come up? They’ll start diving and migrating, and forty-five minutes after sundown, they’ll create light.”

Fucile became involved in the study of bioluminescence more than twenty years ago. “I was on a trip with the Navy to study the phenomena,” he said. “The Navy was interested in it for good guys and bad guys – the good guys want to know if we’re moving through the water, can we be seen,” Fucile explained. “And the bad guys want to know if we can see them.”

A lot has changed since then. During that study, the Navy was using a half-ton, million-dollar piece of equipment called a High Intake Defined Excitation photometer to measure bioluminescence in the water. Fucile later came up with, and patented, his own disposable version of the instrument that costs about $300. But even with advances in technology, there is still an ocean of unknowns.

Dr. Tracy Mincer, Fucile’s colleague at WHOI, has also been researching bioluminescence. He, too, has installed luminometers on various ships in an attempt to quantify both the color spectrum and the intensity of light coming from organisms in the water. Aside from national security interests, the goal of all this measuring is to understand the role of plankton in the ecosystems, both around the world and on the Vineyard. In particular, Mincer has recently been looking at the interactions between bioluminescence and plastic in the ocean, though it’s too soon to draw any conclusions. Other scientists, meanwhile, are researching the effects of human-caused nitrogen loading and ocean acidification on the ocean’s microscopic ecosystems.

Even with unlimited research dollars, one suspects the mysteries would abide. “Bioluminescence is a broad term to describe a whole range of organisms that emit light,” Mincer explained. “Trying to take a measurement of something that has a mind of its own. Did it rain the day before? Did it encounter a migrating herd of bluefish?

“Most people don’t even realize what the process is going on around them, and it’s been here since the beginning of time,” he added. “Organisms gave off light in the very beginning and they always have.”

Most people, perhaps. But for those who are initiated into the unregulated and almost secret society of night swimmers on the Vineyard, if you know the good spots, you’re golden.

Friends Madeleine Ezanno and Neil Hellström recalled long summer night swims across the Island. Their favorite spots include State Beach, Eastville Beach, and Lambert’s Cove. Near the Edgartown Lighthouse is also a good bet. But last summer at Red Beach in Aquinnah, Ezanno had the bioluminescence experience of a lifetime.

“We were glowing in the dark; it was dripping off of us,” she said. She usually finds herself swimming at night a few times a week, depending on the warmth of the summer, but this night was different. “It was insane. We saw trails of it coming off us on the beach. It was the most I’ve ever experienced in my life.”

Hellström prefers Eastville for the post-swim stargazing. “First you go to cool down and then you end up playing in the water. Then you wind up lying on the beach and seeing the stars come out, so not only are you twinkling from the water, but above, too,” he said. “It’s so beautiful.”

Both Ezanno and Hellström work in restaurants and catering, so a cool-off after a long night’s work is almost always in order. “The best part of the experience is to get the warm, sticky day off your body at nighttime; it recharges you,” Hellström said. “It makes you feel like a kid because it’s glowing. It becomes such a playful experience.”

“Sometimes I’m not in a mood for a bar scene after work, but if you’re winding down, a swim is perfect,” added Ezanno. “I’ve done it a bunch of times after dinner parties. It’s a fun way to be in a group and have an experience together.”

Both agreed, there is only one way to describe the experience of diving in and out of glowing blooms and standing side by side wrapped in towels as you swish your feet in the breaking waves.

“Once the glow comes,” Hellström said, “it’s such a magical experience.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)