In 1965 a small group of concerned citizens gathered at artist William R. Leigh’s home on Stonewall Pond in Chilmark to discuss how to preserve the beauty of Martha’s Vineyard. The immediate impetus was concern that a new road proposed in Gay Head (now Aquinnah) might result in the unspoiled Lobsterville moors being carved up and developed. The group quickly grew and, by the end of the year, had a name: the Vineyard Conservation Society. It also had a far broader mission than just preserving the moors: it aimed to save the Island from the entire range of inevitable and often detrimental human impact.

It’s hard today to imagine just how unprotected the Island was fifty years ago. Thanks in part, and often in whole, to the advocacy efforts of the Vineyard Conservation Society (VCS), we now have zoning laws. We have recycling. We have the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, and a small but permanent legal fund for environmental and conservation battles. Cranberry lands have been preserved, and hundreds of trails and ancient ways have been created or protected. The Gay Head Cliffs are federally registered as a national natural landmark. The Polly Hill Arboretum and the Agricultural Society fairgrounds are protected, as are open spaces like the Katama plains, Moshup Trail, and where it all started, Lobsterville. Up-Island and down, the organization has helped private landowners to protect their properties large and small with conservation and agricultural restrictions.

There are also things we don’t have, thanks to VCS’s willingness to fight the good fight over the decades. We don’t have an off-Island-sized shopping center with more than three hundred parking places near the Tashmoo Overlook. We don’t have a suburban subdivision around Waskosim’s Rock. We don’t have three more golf courses, or a sewage plant in the West Chop Woods sanctuary. So it was with understandable pride and gratitude that supporters of the organization celebrated its fiftieth birthday with a series of events last year.

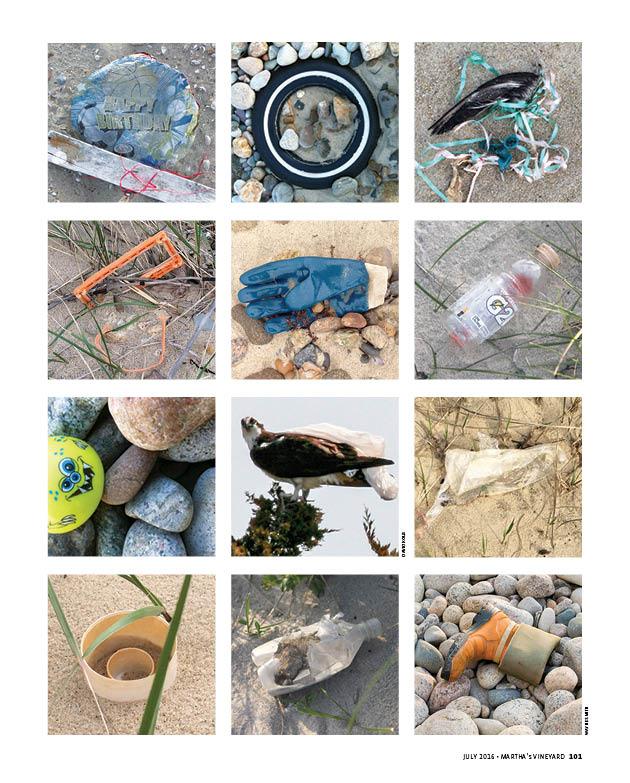

But what about the next fifty years? In many ways, fifty years ago was a simpler time. There were far fewer people, fewer homes, fewer cars, less impacts as a whole. Today, the burden on Martha’s Vineyard is so much larger and grayer. How can one organization really help a community prepare for the ice cap to melt? What can we really do about the people who buy helium balloons or single-use plastic water bottles on the mainland and let them go into our air or waters, littering our shores and poisoning our marine ecosystems? How can we universally change the way we treat human waste and trash? And who is going to foot the bill for this? The Vineyard Conservation Society does not have an endowment. Its annual budget is a reflection of membership dues and the occasional fundraiser. In other words, its ability to advocate for the Island is proportional to the generosity of the public.

Besides, some of the old battles are not entirely over. According to VCS’s statistics, of the Island’s nearly 60,000 acres, roughly one-third has been protected by the various conservation organizations. But, its literature notes, “while this is a remarkable achievement, less than half of the remaining 40,000 acres is ‘built out’ to the limits of current zoning, leaving more than 20,000 acres vulnerable to development.”

There is more at stake in the scramble for acres than open space, rare habitat, and viable farms. Many Island ponds and waterways are imperiled due to nitrogen runoff, septic systems, and other human impacts, such as environmentally unfriendly moorings, leeching bottom paints, and anchoring in fragile ecosystems. In 2010, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission completed a seven-year water resources survey that found that, by a range of measures all across the Island, “water quality was undesirable over the time period of the sampling program.” Five years later, things are only worse.

Last but not least, there are the people. Fifty years ago the summer population of the Vineyard was estimated at around 40,000. Today, the Island in August is home to more than 100,000 people. With them come cars, consumption, solid waste, human waste, and trash. In other words, going forward VCS has a large charge to lead.

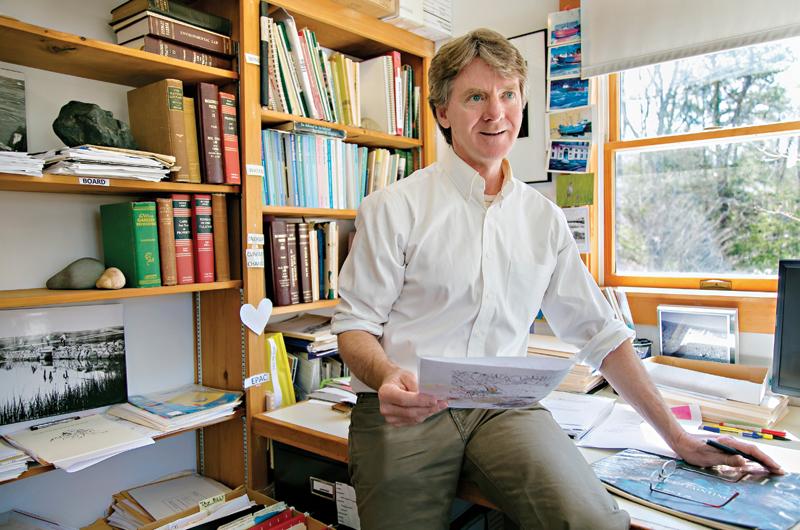

Brendan O’Neill, the executive director of VCS, sat with a large stack of notes on a picnic bench, running through a list of critical topics that he and his staff feels needs to be addressed. The bench overlooked a cranberry pond and the twenty acres of protected land that surround the Wakeman Conservation Center, home to VCS and other Island conservation groups. In addition to the various issues already noted, O’Neill mentioned several others that are perhaps less obvious to an outsider. Under the rubric of advocacy and education, he stressed the need to recruit and educate the next generation of conservationists and energize them to carry on the effort. And the need to ensure that VCS, the organization, stays healthy and vibrant so that it can continue its work for the next fifty years

Save the planet and save itself. How can one small organization funded largely by local donations tackle all of this? O’Neill, who has run the organization for more than thirty years, shook his head.

“We can’t,” he said, and paused before continuing. “One of the greatest things about the Vineyard Conservation Society is that we rarely act alone. We work with other organizations, groups, and the community at large. We have relationships with the Land Bank, Sheriff’s Meadow, the Trustees of Reservations, the MV Shellfish Group, the Wakeman Conservation Center, the Steamship Authority recycling program, the Living Local Harvest Festival…I could go on and on with a long list of who we work with.

“And there is also the community at large who come to us with questions or support our endeavors. The Vineyard Conservation Society is about protecting the Island. We are now at the point where we need to inspire the entire community to come together and say, ‘What are we all going to do together?’”

He sighed, seeming a bit fatigued by the very thought of inspiring thousands to change their consumerist ways. Then O’Neill, who is known for being a mild-mannered, albeit relentless, advocate and negotiator, rather than a Greenpeace-style agitator, smiled. “Really, we must all become conservationists.”

VCS board member and education coordinator Samantha Look put the same thought more bluntly, “We need to create a new normal,” she said. “I get scared when I think about this new normal. Because I know there are lots of things I’m addicted to that I am going to have to give up if I really am going to put my money where my mouth is.”

Look, who grew up on the Vineyard and returned to start a business, first got involved with VCS when she was asked to be on the board. She believes that education is one of the best ways to cultivate these new behaviors. For the last fifty years, VCS has operated under the notion that encouraging and facilitating nature appreciation results in people becoming more inclined to join ventures to protect and preserve the Island. With this goal in mind, VCS has led walks and published such books as Edible Wild Plants, Walking Trails of Martha’s Vineyard, and the Island Adventure Book for children and their families. While this approach has served and continues to serve VCS incredibly well, Look believes going forward that VCS needs to ramp up its education, in order to move more people from passive appreciation into action.

To that point, one of VCS’s newest initiatives is an effort to ban single-use plastic bags on the Vineyard. “Yes, there are lots of other kinds of trash that also need to be limited – single-use water bottles, take-out containers, balloons – but it is symbolic,” explained Look. “Banning plastic bags is a way for everyone to begin thinking about their consumption and trash.” She smiled. “It is also one thing that is not so hard to give up. And it will make a difference.”

“Yes, we have focused on appreciation of nature and will continue to,” echoed Jeremy Houser, VCS’s communications coordinator and resident ecologist. “People appreciating nature can compel them to take steps to protect it. But we also felt something must be done that might motivate people to do the right thing. We began with the idea of banning single-use plastic water bottles. There is absolutely no question that that would do good, but we saw some major political roadblocks and wanted to present something to the towns that we felt we could get passed.”

One of the community leaders who has been a particularly outspoken advocate for the bag ban is Constance Messmer, a writer who happens to also be the wife of Cronig’s Market proprietor Steve Bernier. (She convinced her husband to also stop selling balloons.) “I am eternally grateful to VCS and their team of volunteer workers for re-charting our course in this matter,” she said. “The goal is to do right by the environment and the long-term health of us, our coastal position, and the planet. I find so many single-use bags and bag fragments when I walk in the woods or along the ocean and drive down our roads. I’m tired of seeing them and picking them up. Most dumps won’t even take them as part of their recycling program. It’s an easy change.”

So far, the larger Vineyard

community appears inclined to agree.

This past spring, VCS’s Bag the Plastic Bag initiative got a proposal for a ban on five of the six town warrants, and all five, Aquinnah, Chilmark, Edgartown, Tisbury, and West Tisbury, passed it with great enthusiasm. (Oak Bluffs selectmen initially put the ban on the town war-

rant, but then took it off when a dozen

or so businesses complained.)

“I am, needless to say, incredibly excited by this outcome,” said Look. “On the one hand, it looks like a small step. But it is something that impacts all of us in one way or another, and it has not been a simple question for the Island…When it came time to vote, it did not just squeak through. It was a resounding majority, and the room erupted in applause.”

In a related effort aimed at lessening people’s dependence on single-use plastic water bottles, the VCS team is developing an initiative to install water filling stations around the Island, similar to those found in many major airports. According to Signe Benjamin, VCS’s programs and membership director, the organization has so far funded a water filling station for the high school, and is exploring getting them installed in all the schools. “We need $4,000 to install and endow each station,” Benjamin said. “We are incredibly excited to be putting one in at the high school.”

When the stations are in place, instead of bringing plastic water bottles to school, kids will be able to bring their water bottles to school and fill them with clean, filtered, cold water. “So rather than telling people what not to do, we are giving them a great option for what they can do, reinforcing positive, environmentally friendly habits,” explained Look.

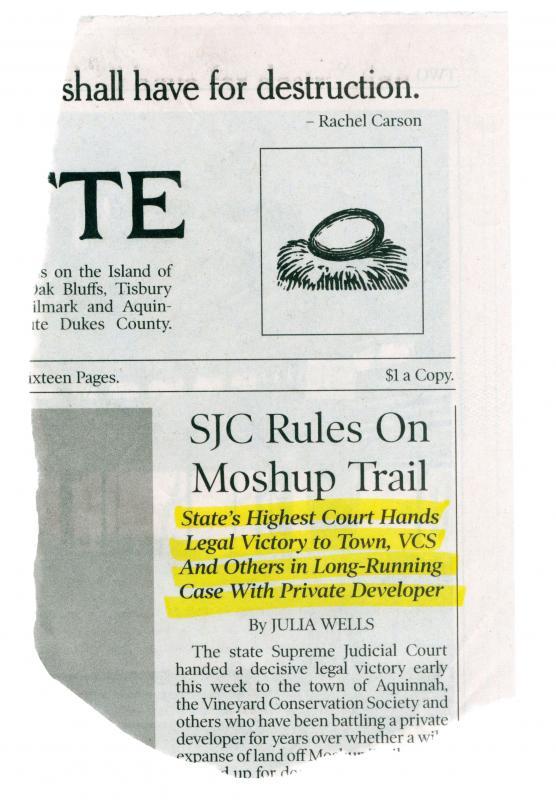

In many ways, the quiet appearance of low-impact water stations in the public schools and the disappearance of single-use plastic bags from shops will be classic VCS achievements. Because VCS does not manage conservation properties, even though it often helps facilitate the process of conserving land, there are no preserves with the name VCS on them. There are no signs at the dumps that say “recycling brought to you by the Vineyard Conservation Society.” For nearly twenty years VCS has fought a protracted legal battle to prevent scattershot development of the fragile moors of Moshup Trail in Aquinnah. The case finally made its way all the way to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, the highest court in the Commonwealth, which in April handed VCS and the town of Aquinnah a sweeping victory. But all casual drivers up-Island are likely to know is that the road is as beautiful as it ever was. “It’s been a two-decade-long fight, defending the integrity of this remarkable conservation land,” said O’Neill. “We are gratified with the outcome, and hope that the effect will be to allow even more conservation to occur.”

Make no mistake. No one at VCS thinks a few water stations and a ban on single-use plastic bags will solve the problem of an ocean full of plastic refuse, but they are surely a step along the way. Similarly, they know that solving the water-quality crisis is going to require a wholesale rethinking of how we process wastewater – 80 percent of the nitrogen loading problem is caused by human urine leaching from individual septic systems. O’Neill believes eventually the six towns will need to empower a regional authority, probably the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, to enforce a “No Net Nitrogen” policy, where all development must offset nitrogen produced, either on-site or through acquisition of land off-site dedicated to open space.”

But even as VCS advocates for at least beginning the hard political conversation about large-scale solutions, the Martha’s Vineyard Boards of Health and the Martha’s Vineyard Commission in 2014 pursued and succeeded in getting passed a new bylaw in all six towns to regulate the sale of lawn fertilizer, a major source of nitrogen loading (and other poisons) of our ponds and estuaries. They also published a brochure, which is available online, and at garden stores like SBS and Jardin Mahoney. Most important, perhaps, they worked with Michael Loberg, chairman of Tisbury’s Board of Health, Matt Poole, Edgartown’s health agent, and three professors from the University of Massachusetts to educate 180 landscaping professionals in the application and use of fertilizer.

“At the outset, we agreed that if we won this thing, it will have an effect on only a handful of the worst offenders, but that it would be worth it,” said Poole of the effort. “It’s only been one year, but I’ve been pleased with what I’ve seen. We gave out eighty-eight professional licenses this year,” each of which cover up to eight employees. “And the mainstream garden stores did a fantastic job of educating their customers, and are, by in large, offering better products. I don’t know of any town who wrote a ticket. And during fertilizer season on my walks into town to work – I park out of town – I didn’t see any fertilizer on the sidewalks, which was a first. It could be a coincidence. But are we seeing more scallops because of the fertilizer regulation? That’s hard to say.”

Poole continued, “But I do feel we now have an audience that is poised for the next step. The people who came to the workshops we held have asked for more workshops, more information. And I think people now know that if you drop a pile of fertilizer on the driveway, you should clean it up. Don’t just blow it into a hedge beside the driveway. But no one has taken this on as their primary topic. So, again, there’s definitely room for us to continue. We just need to do it. We need to decide to do it together.”

Doing anything together on the Vineyard can be a challenge. As they look forward to the second half-century of advocacy, O’Neill and his younger staffers see changing that reflexive provincialism as a goal unto itself. To the old adage “think globally, act locally,” they might add, “but not too locally all the time just for the sake of being ornery and local.”

“One of our long-term goals is to get people to think about the Vineyard as a whole, get it to have a regional identity,” said Benjamin, who worries that the six towns, which all have their distinctive personalities, will not rally together and work toward the same goals. Benjamin, who grew up on the Island and returned after college and travelling to raise her family here, said, “While I love each of the towns, it really slows down the ability to affect change. For instance, with the plastic bag ban, we’ve had to go to each town’s board of health, board of selectmen, as well as business owners and community leaders.”

Her colleague Houser agreed. “Yes, last year we thought, ‘Plastic bag ban: easy,’” he said. “Not so easy. It has taken a huge amount of time to get the ban on the town warrants. And, then we have to get the residents of each of the towns behind it.”

The Island economy, too, presents something of a challenge going forward. “I think we are past the point of thinking that we can create a broad, self-sustaining diverse economy here,” said Houser. “Nor is there a real possibility of us having some sort of idyllic, commune conservation fantasy. For better or worse, we are a tourist economy and we need to figure out how to work within that framework. In a sense it is the extraction mine theory, like the mining business. We have to monetize our resources. It is inevitable that we harm our natural resources as we enjoy them. There’s that great saying that people who love nature do far more harm than the people who stay away from it. So, how can we help people who come here understand their impact and minimize it?”

“We are activists at VCS, but we are also thoughtful. We take our time thinking and talking,” said Benjamin. “Another example of this is the offshore wind project. We really did our research before we offered a position.”

“And the end result is better,” Houser agreed. “It was improved by discussion. The farm is farther offshore. We held out and got a better deal.”

Hold out for a better deal, and in the meantime take every small step you can toward a sustainable Island. That, one senses, is a pretty good statement of VCS’s philosophy and strategy.

Back at the picnic bench, O’Neill took a sip of water and reflected on VCS’s approach. “In so many ways, our job is to facilitate partnerships, create conversations, and make connections. It is slow, unglamorous background work. But the urgency of what needs to happen is increasing. And our relationship with the land is emotional.

“I wonder how the community on this Island will regard itself? Will it value what we have and go to any length to save it? Will we be proud of our conservation efforts? Or will we let it be destroyed?”