Each spring Buddy Vanderhoop bites the head off the first herring he catches.

“It’s just traditional and it’s been done forever and it brings you luck,” he said late this winter, a few weeks before the earliest alewives and blueback herring – the scouts – began to fight their way up his herring run. “It’s like it’s between you and the fish, your blood mashing with the fish’s blood. You don’t just bite the herring head off and spit it out. You bite it off and eat it. So it’s a little crunchy.”

Inside the Aquinnah Shop Restaurant, which stands high over the Cliffs that front the sea, Vanderhoop looked at a picture of himself, smiling, with the body and tail of an alewife dangling from his fingers. He thought back to that day, laughed, and said, “It’s actually pretty tasty.”

Herring return to the sea in this rare film clip from 1935. Read more about the historic footage here.

Vanderhoop, a man of burly, cheery, loquacious spirit, is a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah). As a descendent of the first people on Martha’s Vineyard, he might be the only man in the state still allowed to seine alewives and bluebacks, collectively known as river herring. A tribal member who fishes from a run on tribal land, Vanderhoop can take all the herring he wants to eat or give away.

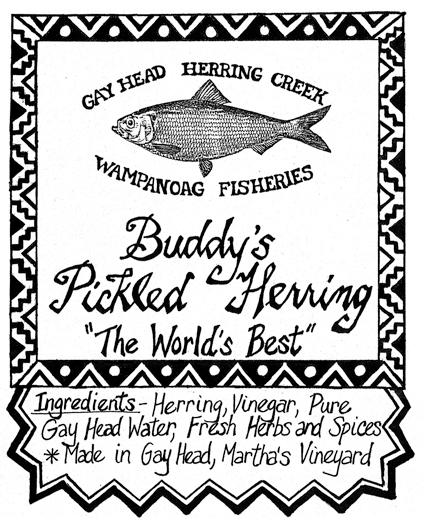

But for the last eleven years, he hasn’t been allowed to sell it to tackle shops or lobstermen for bait, market jars of Buddy’s Pickled Herring (“World’s Best”) to connoisseurs, sell the salty and alluring roe to visitors, or even use it to bait hooks when he takes charters out to waters where, in the springtime, ravenous striped bass wait.

For more than 160 years, at the far western end of the Vine-yard, Vanderhoop, his ancestors, and other tribal members have leased a herring run, first from the town of Gay Head (now Aquinnah) and more recently from the tribe. The run meanders from saltwater Menemsha Pond to freshwater Squibnocket Pond. Things were going fine until 2004, when suddenly the populations of river herring – both alewives and their close cousins, the bluebacks – nearly vanished from streams, runs, and ponds up and down the eastern seaboard.

A year later, at the end of 2005, Massachusetts joined Connecticut in imposing a moratorium on fishing all the creeks, manmade runs, and freshwater ponds to which alewives and bluebacks return each spring to spawn. Rhode Island soon followed suit. The fishing ban also covered state waters to the federal line three miles out. Vanderhoop was seining alewives from the old Aquinnah run one morning when the environmental police showed up and told him that for commercial purposes, he had to stop.

“No idea that this was going to happen whatsoever,” he said. “I was making a good $40,000 a spring. And you know, that little piece of the picture was paying my mortgage and, you know, helping me get by for the year. I depended upon it. And all of a sudden, out of the blue, they take $40,000 out of my pocket. So it was a bitch to make ends meet after that happened, you know?”

The moratorium was supposed to last three years, but the alewives and bluebacks did not recover. It was extended another three years. No luck. In 2012, a commission of all the states along the East Coast renewed and extended the moratorium indefinitely. From that point forward, if a given state wanted to open even a single run where it looked like river herring might be doing well, such as Vanderhoop’s this past spring, this commission would have to approve. Just collecting the data and making the case could take as long as a decade. Only a few towns in Maine with thick sheaves of data have since won the right to start fishing for river herring again.

Vineyard fishermen have always set out in boats to catch swordfish, lobsters, cod, haddock, and flounder. But river herring swim to the fishermen, who net them in streams or runs – narrow wooden canals that help to guide the fish from the saltwater world where they live most of the year to the freshwater one where they spawn. The fishery doesn’t sound terribly adventurous, but in its heyday the thrill of the spring arrival of herring could not have been sharper.

“Excitement reigned when the word was passed that the herring had struck,” the Vineyard Gazette reported in 1929, already looking back with a hint of nostalgia to an earlier fishery. “The seines were loaded into wagons. Men rode and ran as they gathered for the seasonal slaughter of fish. Surf nets – huge, bowed affairs – were employed and it is related that on one occasion a man who had lain on what he swore was his deathbed throughout the winter, leaped to his feet, hauled on his boots and grabbed his surf net when he heard that the herring were running, and, wading into the surf up to his chin, came out with the net filled and hanging over his shoulder, and never knew another day’s illness. Such was the electrifying effect of this welcome news on the Vineyard inhabitants.”

Records show that European colonists began leasing the right to seine river herring from Island sachems only a few years after settlement in 1642. State documents from a hundred years ago list runs in all six Vineyard towns – fourteen total, most of them already fifty years old at least.

In those days, schooners from Gloucester hand-lined cod from dories on the Grand Banks, baiting their hooks with herring. They sailed out of their way, around Cape Cod and over perilous Island waters, to buy Vineyard river herring. In one early April week in 1894, five schooners took 55,000 alewives caught from the Mattakesett Herring Creek, a mile-and-a-half-long channel dug parallel to the Atlantic coastline between Katama Bay and Edgartown Great Pond. Fights broke out on the wharves for the right to buy the first barrels carted to the boats.

As a boy, Vanderhoop used to visit the Gay Head herring run with his father, William Sr., who worked it with Jesse Smalley, George Cook, and Edmund Cooper. “I was just amazed when I went down there,” Vanderhoop said. The men baled three or four trailers full, four nights a week. They left three nights for the fish to swim up the run and spawn unassailed.

“I used to go down – my mother yelling at me because I came back totally covered with mud and scales and smelled like a fish. My good clothes were covered. I was down there catching herring with my hands, and then I’d put them on a string and I brought them back, about twenty-five or thirty of ’em.” Thus began a lifelong love for a fishery that fulfilled him body, soul, and bank account.

In the early years of this century, the Island invested eagerly in the restoration of old runs and the building of new ones. A sluiceway was built at the western end of Mattakesett Creek

to help herring once again reach Edgartown Great Pond.

Runs were built at the head of Lagoon Pond and Lake Tashmoo. Efforts were begun to help herring work their way up miles of streams to freshwater ponds in West Tisbury. Then came the moratorium, whereupon everything and everyone stopped. Everyone, that is, except Vanderhoop, who by rights as a tribal member was left to seine on tribal land just for himself, his family, and his friends.

Alewives and blueback herring are anadromous fish, living mostly in the ocean but returning to spawn in the exact same freshwater rivers and ponds where they themselves were hatched. You can’t overstate the importance of river herring to the food chain in the Atlantic, Vanderhoop said. “Herring is the main staple for almost every fish in the ocean. I mean, scup and sea bass, they eat the fry. Flounder eat them, all the way up to striped bass, bluefish, tuna fish, whales: Everything in the ocean including human beings eats herring.”

But alewives and bluebacks do something else of crucial importance to the ecology of the ocean and freshwater streams and ponds where they swim. “They’re moving nutrients and energy from the ocean up into freshwater systems,” explained Eric Palkovacs, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California-Santa Cruz who specializes in the study of river herring. “So they have a really important role in lake food webs. Adults excrete nitrogen and phosphorus in freshwater systems, and the juveniles move those nutrients from the fresh water out to the marine. They’re a link, they’re the key.”

The herring don’t just need ponds that are alive and vibrant, in other words; the health of the waters depends on the herring. And yet – apart from recent signs of hope at Vanderhoop’s run – the fish are clearly declining. Estimates are that along the East Coast, river herring are down to five or maybe even just two percent of the population known to exist in 1970. Along the shorelines of Connecticut and Rhode Island last spring, there was a terrifying drop in the count at many closely watched streams and runs. “Sites where we had been able to count, over the past decade, several thousand fish, we were getting less than a hundred fish,” said Palkovacs. “Absolutely horrendous and really scary runs.”

For years, officials and scientists laid considerable blame for the deepening crisis upon the poor health and inaccessibility of freshwater streams and ponds. But many of the dams built in the 1800s and early 1900s, which had blocked passage of the river herring, have been taken down. Pollution that soured the spawning grounds in ponds and streams was reduced after the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972.

“You know, a lot of the worst problems have really been mitigated, and water quality is as good now as it’s been in a really, really long time,” said Palkovacs. “If it was really only the fish passage issue, or if it was really mainly the pollution issue, those things have gotten a lot better. But at the same time, especially over the past twenty years, the population has continued to decline.”

The problem now, say environmental groups and those who fish recreationally or commercially near the coastline, is a voracious offshore fishery for Atlantic herring, a cousin to the ale-wives and bluebacks. Also known as sea herring, the Atlantic herring share the same silvery-green color, sleek dorsal fin, and big-eyed stare, but they remain in the ocean their whole lives. In the past twenty years or so, giant midwater and pair trawlers have been sweeping the sea between the surface and the bottom for Atlantic herring and mackerel, which industrial fishing companies prize for lobster bait, fish meal, cat food, and canned food, often for export. And though river herring are illegal to sell commercially, at sea they often travel with their oceanic cousins and get taken as by-catch.

“They’re the biggest fishing vessels on the East Coast,” said Roger Fleming of Earthjustice, a San Francisco law firm advocating for environmental causes. “They’re ships; they can be up to 165 feet long, dragging football-field-sized nets, often between two of these trawlers.

“And it’s small mesh. It catches everything that’s in its path. River herring, when they’re out at sea, they mix with Atlantic herring and mackerel. They get caught. Unless you have observers on the vessels, we don’t know how many of them are being caught. A lot of them are dumped at sea, I suppose, if the vessels identify them as river herring and are worried about landing thousands of pounds of the wrong species.”

For the most part, the by-catch of river herring takes place in federal waters, outside the three-mile boundary of protections put in place by the various Atlantic states. Though river herring have long been listed as a species of concern by the federal government, in August 2013 it declined to list them as threatened, saying there weren’t enough data to warrant it. Despite court rulings, the government has so far failed to create a management plan for alewives and bluebacks in federal waters. But in January of this year, Earthjustice won a court order that requires the National Marine Fisheries Service to fully analyze the state of the fishery and, based on those findings, actually decide whether it deserves a management plan that would build up the populations again. There is also a suit to have both species listed as threatened.

The fishery for Atlantic herring and mackerel is heavier in federal waters off Rhode Island, Cape Cod, and the Islands than anywhere else, said Palkovacs. He and his colleagues have been testing samples of river herring raked in as by-catch by midwater trawlers for the past three years, and not surprisingly the genetics show that vessels trawling just beyond Vineyard waters are taking a great number of fish that spawn along the nearby coastlines of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.

But what startles Palkovacs and his colleagues is that “we also see a high percent of southern New England genetic stocks being caught in other locations too.” In fact, more river herring from the southern New England shoreline are being caught in the Gulf of Maine than those born in the gulf itself. It’s not exactly clear why. But it appears our homegrown population – what’s left of it, anyway – is exceedingly mobile in its migration, and therefore especially vulnerable to being caught and killed up and down an important length of the coastline.

The by-catch of river herring in federal waters is not totally unregulated. In recent years the New England Fishery Management Council, a federal agency, capped the amount of river herring and shad that could be taken in federal zones off Cape Cod and southern New England at 312 metric tons, with each metric ton representing roughly 11,000 fish. But last year, just as Palkovacs and his colleagues were witnessing the disappearance of alewives and bluebacks all along the Connecticut and Rhode Island coastlines, the same federal council voted to raise the cap, possibly doubling the amount that could be caught in waters off Cape Cod in 2016.

Critics say large fishing corporations, which have representatives on the council, want to ensure that by-catch limits are set so high they will never be met, since reaching them would shut down the lucrative Atlantic herring and mackerel fisheries for the season. But there isn’t much risk of a shut-down happening, most everyone agrees, because there aren’t enough observers on the boats or at the wharves to count how many river herring are actually being snared. The federal government hasn’t budgeted the money for it, and state officials and the industry say the fishermen can’t afford to pick up the tab.

“They’re hard-pressed already and we have a fishery disaster here in New England and they can’t pay for it,” said David Pierce, who serves on key boards – at the state level as director of the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and member of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission; at the federal level on both the New England and Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management councils. In these roles, he advocates for the fish as well as for the fishermen who steam from Massachusetts ports: “So it poses a tremendous problem

for regulators, for managers. We need to know what’s being caught. But we cannot shift the burden onto the backs of the fishermen. It’ll break their backs.”

Pierce wants the federal government to pay for the observers, but agrees that the way things are going in Washington there’s zero chance of that. Fleming, of Earthjustice, said an effective management plan “should have catch limits that are based on the biology of river herring, that would set the levels low enough so that the stocks would have the chance to rebuild. We could identify where by-catches are happening most often and try to limit by-catch, and we should protect their habitats as well.”

There’s a bit of an Orwellian flavor to it all. At the same time that the federal government has doubled river herring by-catch limits for giant ships at sea with little or no study of the implications of doing so, the inshore regulations designed to promote the recovery of the species require a single fisherman like Vanderhoop to provide a decade’s worth of data before he can catch and sell a single herring.

Paul Bagnall, the Edgartown shellfish constable, realizes he’ll have long retired by the time the Atlantic commission permits the reopening of the weedy Mattakesett Herring Creek, which supplied Gloucester fishing schooners with 55,000 herring one early week in April of 1894. Edgartown, he said, hasn’t even started to collect the required data. “Not enough fish are running in Mattakesett for me to even try and get volunteers interested in counting fish,” he said, “because there’s got to be some for them to count. Now if I see twenty fish on an early morning, I get excited.”

The numbers appear to be improbably but wondrously better at Vanderhoop’s run at the other end of the Island. “I do go down there and I fish the run pretty hard in the spring for stripers,” he said. “And last year I was down there one night and all of a sudden – I was by myself – there were literally two or three acres of fish breaking out in front of me there. It was just black with herring. It was a great thing to see that. The year prior to that you’d see one acre. Or an acre and a half.”

He’s been calling Pierce at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries to find out when the moratorium will be lifted. The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) has installed

a fish counter in the Gay Head run. Out there somewhere a commercial fishery awaits. Vanderhoop is in a hurry. Let the earliest, unluckiest alewives look to their heads.