At 1000 hours on December 10, 2014, thirteen days after our snowy departure from Martha’s Vineyard, we sighted the steep verdant mountains of Hispaniola rising from the tropical sea piercing the hazy cerulean sky. Landfall is a momentous occasion aboard a sailing vessel. It is a welcome reward following the continuous cycles of life underway, standing watch day and night, observing the constant changing shades of water and sky on the far horizon. All hands shared in the duties required to manage the delivery south: tending sail and taking the helm, navigating and cooking, cleaning and mending as we drove our fifty-foot schooner, Charlotte, through the vagaries of wind and ocean – living and working together with a common goal to arrive safely at a distant land. Landfall is a time for celebration and gratitude.

However, the journey was not yet over. From sighting this majestic island fifty miles to the south, we now had to approach the Windward Passage, sail southwest along the western coast of Haiti to Cap Dame Marie, and then head east to our final destination, a small island called Île à Vache.

We arrived at the northwest coast of Haiti at twilight. With our sails set on a close reach a half-mile or so offshore, we observed as if through an ancient lens the inaccessible, rugged terrain plunging to the sea, shrouded in a smoky, mysterious veil. Dozens of local fishermen who were casting and hauling nets from hand-built sailing boats waved to us as we slid silently along from one coastal village to the next. As the light faded, I stood farther offshore to avoid collision with these beautiful but primitive, unlit and engineless watercraft. Haiti became black as the surrounding night, save for an occasional fire on the beach or in the hills above, with her faint mountainous outline backlit by a waxing moon. We had sailed into another time zone centuries past to a quiet, still, dreamlike place.

A moderate easterly katabatic night wind slid down the high volcanic slopes and across the water, making our way through the Windward Passage between Haiti and Cuba a pleasant reach with sheets eased on an easy sea. Shortly after midnight we rounded Cap Dame Marie and set our course for Île à Vache some twenty nautical miles to the ENE. The cooperative breeze backed a few points to the north, allowing us to make our course in one tack, and by 0300 we rounded up in the lee of a pristine uninhabited cove and set our anchor in the white sand below twenty feet of clear moonlit water.

With sails stowed and Charlotte finally at rest, all hands walked about the deck in quiet conversation observing this wonder of the natural world unchanged by man. For all of us, this was a landfall like no other.

Since my first visit to Haiti in 2011 I’d had a strong desire to return, and stumbling around the Internet one winter evening in 2013, I found a free “Cruising Guide to Haiti” online. As so often happens on our ever-shrinking planet, when I contacted the author, Frank Virgintino, we pieced together that thirty years ago he had sold to our boatyard a large quantity of bronze hardware – at ten cents on the dollar.

“You must sail to Île à Vache,” he implored, and taking his advice I emailed his Haitian friend Sam Altema in Caille Coq, the little village in Port Morgan harbor. Sam responded quickly and informed us of the various needs of his community, and what we could bring to Haiti aboard Charlotte that would be most useful and helpful. My wife Pam reached out to the database of her nonprofit organization, Sense of Wonder Creations, and also to friends of our boatyard, and before long we had an enthusiastic band of donors bringing clothes, books, games, art supplies, and cash to be delivered to a local orphanage run by the impressive Sister Flora Blanchette. I collected bags of old sails and fishing gear to give to the local fishermen, as well as used tools and rigging for the boat builders.

In the mid-nineties I designed our schooner Charlotte to fit a job description that ranged from a family boat capable of cruising with as many as ten relatives aboard, day sailing with a dozen or more friends, chartering with six guests who have no sailing experience, and ocean sailing to distant ports. Compromise is the one constant in yacht design, and she is a low-tech, semi-gloss comfortable creature that is as easy on the helm as she is on the eyes.

But the schooner rig evolved during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for working vessels fishing and carrying cargo coastwise as well as offshore. And by late October 2014, Charlotte was laden with cargo liberated from America’s dumpsters, mostly, stowed below deck in every available space including the bilge.

Preparing for a December offshore passage from New England to the lower latitudes requires careful examination of your vessel and its multitude of parts, from the masthead to the bottom of her keel. A long “to do” list was prioritized and, with the help of my companions, the work was accomplished over several weeks with only a few minor projects left for another time. Essentials were gathered, such as nautical charts, plotting instruments, cruising guides, a nautical almanac, sight reduction tables for celestial navigation, sextant, courtesy flags for every country intended to visit, pelagic bird and tropical fish guides, tide books, tackle box, first aid kit, sail repair sewing and rigging bag, spare parts for the engine, water pumps and other mechanical/electrical equipment, backgammon board, dominoes, playing cards, music, and don’t forget toilet paper. Diesel fuel, potable water, propane for the galley stove, and the provisioning of staples of food rounded out the commissioning task.

We hauled our wooden rowing tender aboard using the fisherman sail halyards and lashed it securely along the port side deck to the stanchions and deck house grab rails. Jack lines were bound taut along the deck to provide quick access for clipping in the safety harness lanyards. Lifelines at the rail, footropes on the bowsprit, man overboard pole, life ring, and strobe light were all tested for sea. I prepared an emergency “go” bag to include the emergency GPS beacon (EPIRB), first aid kit, distress flares, water bottles, and some dark chocolate. The life raft was made fast to the cabin top amidships.

Selecting your shipmates is an easy task on the Vineyard, given the vast pool of competent sailors who readily succumb to the lure of mysterious tropical islands and all their enticing possibilities over the alternative of old man winter who grips our northern terminal moraine and its captive inhabitants with unbridled enthusiasm. My first requirement was to find a mate who could look after Charlotte in Haiti when I returned back up north. My friend Ian Ridgeway and I had been talking about this eventuality for several years and now the planets were aligned in their proper order, terrestrial bonds were laid aside, and Ian committed himself to the care of Charlotte for the forthcoming five months. Ian started sailing on the 108-foot schooner Shenandoah on a fifth grade class trip and continued every year working his way up “thru the hawse hole.” At the age of twenty-four he became master of the ninety-foot schooner Alabama. His knowledge of the sea and the way of a ship, his musical ability, good humor, and gracious nature put him at the top of his game. Without Ian to fill this vital role, we could not have made the voyage.

The Gannon & Benjamin boatyard is also a recruiting station for sailors in a casual serendipitous arrangement where shipwrights occasionally disappear from their usual place at the workbench to a position aboard a vessel outward bound. Usually, we (the managers) are aware of such departures. To my great relief, Brad Abbott and Zoli Clarke were both willing to abdicate their earthly responsibilities and join the jolly crew of Charlotte, proving once again that no one is indispensable – or, to paraphrase one astute psychologist, “The cemeteries are full of indispensable people.” Brad and Zoli brought a wide range of skills in their respective sea bags and are most enjoyable companions.

While the Commanders’ Weather service continued to advise us to postpone our departure due to a succession of frontal systems producing unpleasant southerly gales, and the psychological effect those predictions foster, I decided to take on another crew member at the eleventh hour to ease the burden for the rest of us. I called on my old friend Malcolm Boyd the day before Thanksgiving to see if he would join us – a simple request, I thought, and much less alarming than specifically asking him to leave his job and family for an unknown period of time with no pay to go thrash about in the North Atlantic in December.

He replied, “When do we leave?” I suggested, “Tomorrow?” in light of the recent more-promising weather forecast. But of course no one wants to leave family and friends, turkey and yams on Thanksgiving Day, and so weather oracles notwithstanding, we set our ETD for the day after holiday stuffing.

There is a history of migratory sailing vessels casting off from Vineyard Haven when the daylight shrinks to darkness before dinner and the cold north wind begins to moan in the rigging. The sixty-five-foot Gannon & Benjamin schooner Juno is a veritable commuter to the West Indies, missing only one season in thirteen years when Captain Scott DiBiaso sailed her to Europe for a summer in the Mediterranean. My partner Ross Gannon and his family migrated to “the islands” aboard their forty-five-foot sloop Eleda for the winter of 2013–14. Rick and Chrissie Haslet have completed two round trips aboard the impeccable ketch Destiny, and Todd Bassett and Lee Taylor continue to cruise south in their classic yawl Magic Carpet after sufficient recovery from their previous escapades.

Is there a pattern here? Why do we do this?

Rest assured, when the wind begins to howl and the seas build into mountains and toss your precious varnished cockleshell like a cork in a washtub while the lee rail beckons for the contents of your last meal, all those indestructible cast bronze fittings, that stainless steel wire rigging, and the basket of boards screwed to frames with cotton string caulked into the seams – in other words, the vessel – suddenly begins to take on an esoteric Eastern philosophical atmosphere. As in the impermanence of all things. Nothing, absolutely nothing will convince you that this ocean voyaging business is a good idea.

But there is no time to dwell on the regrets of the unraveling situation. Rather, you deal with the elemental present reality knowing that you are in your right place to keep your vessel and shipmates secure for the duration. Eventually, the storm ends, the sun appears, and the mercifully short memory of the sailor allows him to carry on with impunity.

With those cheerful thoughts forgotten, we set sail on

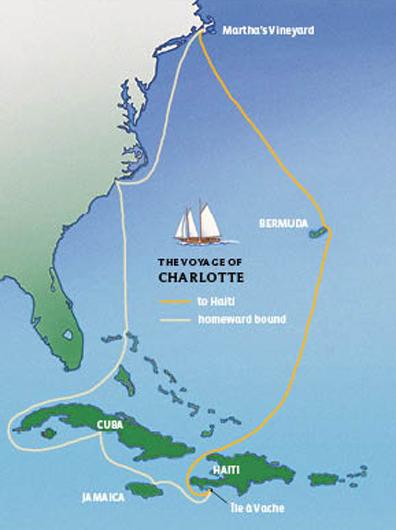

November 28 with a forecast of freshening north wind and snow flurries building to what the old timers used to call a “pleasant gale” from the northwest or well abaft the beam. The reefed mainsail, foresail, and forestaysail provided plenty of canvas to drive Charlotte’s 58,000-pound displacement out of the harbor and fly her along at hull speed up Vineyard Sound with a fair tide past the Gay Head Light, where we set our course to Bermuda, six hundred fifty nautical miles to the south-southeast.

The first bitter cold night gave way to a blustery sunny day as Charlotte charged southward with all hands adjusting to the rollicking motion and post-Thanksgiving digestive cycles. By the end of the second day the wind moderated and all sail was set – mainsail, foresail, forestaysail, jib, and fisherman staysail. That borderless river of tropical water known as the Gulf Stream greeted us with leaping dolphins, a welcome of warm air, and a favorable current. We shed our winter woolies and set our inner clocks to the rhythm of our watery world.

I had set a watch system with two men on deck for three-hour shifts around the clock. A careful record of compass heading, average speed, wind conditions, barometric pressure, bilge condition, engine hours, battery voltage, sails set, and the ship’s position were entered into the log book at the end of each watch.

The mariner’s mantra is “constant vigilance.” To let down your guard is an invitation to trouble and all shipmates must be alert to the constant demands of the sea as she relentlessly works the vessel with forces beyond measure. A watchful eye on deck and aloft will detect an unfair lead, fouled line, or chafing sail before the dreaded sound of shredding cloth tells you it’s too late. Keen observation of the sea and sky can keep you clear of a waterspout by day or merchant ship at night.

By the third day at sea our routine was second nature and more activities filled our hours. We took sun, moon, and star sights with my trusty old sextant that has guided me across the ocean for forty-five years. The GPS may be more accurate, but when the screen goes blank or the batteries die, the sextant will never fail you. From the galley a stream of gastronomical achievements were delivered by our collection of accomplished sea cooks with welcome regularity. We were well provisioned with locally grown Vineyard produce and rarely was something delectable not bubbling and squeaking on the galley stove to nourish five ravenous bodies.

We approached Bermuda in fair weather and light air and sailed through the cut to St. George’s harbor on December 2, four days after our frigid departure from Vineyard Haven. We had completed the first leg of our voyage with all hands in fine form and the schooner Charlotte at her best. With our American ensign flying from the taffrail and the Bermuda courtesy flag above the “Q” (quarantine) flag at the starboard foremast spreader, we came alongside the customs dock for clearance.

The courteous welcome from the Bermudian customs officials set the tone for our reception in this lonely mid-Atlantic volcanic archipelago surrounded by pale turquoise sea lapping at pink-white sand or colliding against rugged rock-faced bluffs and nourishing the thriving coral terrace. But we did not tarry long. After a flurry of provisioning, filling tanks, replacing a water pump, and a thorough check of the rig, engine, and ship’s gear, we said farewell to our dear old Bermuda friends, who were the main reason for our visit, and set off again to ride the North Atlantic 1,100 nautical miles south to our winter home, Haiti. It felt good to be back in our sea-rolling world, standing watch with our pals, five bonded boys in a boat. Voyaging under sail is one of humanity’s earliest methods to discover new lands, and such adventure stirs one’s primordial foundation like a lost prehistoric memory rekindled.

A fair wind astern bolstered by a steep confused sea kept the helmsman alert and some appetites reduced as Charlotte boiled along, ticking off the miles day after day. We became reacquainted with the night sky overflowing with stars and stared at the wonders above in the coolness of the tropical darkness. For every sixty nautical miles gained on our southerly course, Polaris, the North Star, slid down toward the horizon astern one degree in altitude, mimicking our latitude.

The dawn watch is my favorite if only for the relief of light following darkness, which in foul weather can be very nerve-racking. After a long and harrowing visionless night watch, a welcome sunrise restores your ability to observe the ship and see how this complex contraption of lumber, line, bronze, and canvas survived the thrashing and pitching in blindness – as if she needs to see. Those lucky souls enjoying the sunrise are also expected to conduct a general cleanup aboard – washing down the cockpit, sweeping up below deck, organizing the galley, and any other tasks required to keep the vessel shipshape.

The traditional midday ritual of calculating our noon sight position gets everyone on deck and offering estimates on the previous day’s run. We had some good ones, the best just over two hundred nautical miles – an average of eight knots per hour.

At sunset we strained our eyes in search of the “green flash,” an optical phenomenon that rarely occurs just as the upper limb of the sun touches the horizon before sinking beneath the sea. No flash this voyage, but stunning preprandial entertainment with the evening sky exploding with colors and compositions that painters can only wish for. The divine fish guardians were clearly in control of our yellow- and pink-feathered lures trolling astern, fouling the hooks with Sargassum seaweed, and protecting the scaly creatures from our baking dish. No fresh barracuda, wahoo, or bonito on this passage, just a comforting sense of our ecological commitment in mitigating the catastrophic overfishing of the world’s oceans as we sank our forks into another bowl of rice and beans, again. Hot sauce, anyone?

At noon on December 8, four days after departing Bermuda, we were one hundred nautical miles northeast of Grand Turk Island, and set our course to take us between the reef strewn Mouchoir Bank and the Turks Islands. Although still three hundred fifty miles from our destination, I sensed a change in our attitudes and expectations. The attentive companionship, communal friendship, and shared experience on an ocean voyage is unique to the exclusive nature of its special environment and purpose. Approaching soundings, where the sea floor rises to a measurable distance below the keel – from miles of depth in mid-ocean to fathoms or feet, and eventually breaking the liquid surface to be called land – we aboard begin to shift our thoughts to anticipation of the excitement of eventual landfall and the bittersweet knowledge that our freedom from those worldly events, a significant part of the attraction of the passage, will also end.

But the friendships made on a sea voyage endure with a timeless quality, like a bond with an old schoolmate from long before you had a care in the world.

We awakened in our secluded anchorage on the south coast of Île à Vache to a light breeze sifting across a palm-fringed white sand beach as captivating and beautiful as it had been a few hours earlier when we arrived under moonlight at three o’clock in the morning. All hands dove over the side for a long swim, something we had been trying our best to avoid during the previous six-and-a-half days since leaving Bermuda. Now we had new freedoms and swimming in this effervescent cove was a welcome change.

Before the sun peeked over the hills to the east, a Haitian fisherman paddled out to Charlotte in his dugout canoe to investigate the rare arrival of an American yacht. He greeted us cheerfully and gestured to the delectable display of fresh fruit and fish on the sole of his vessel. The mangoes and papayas looked like a good complement to the eggs and beans simmering on the galley stove. Conversing in French, I explained to him that we had yet to arrive at the port of entry, Port Morgan, to clear customs and change money so I had no Haitian currency to pay for the fruit. He asked if we had an old piece of line for trade, which of course we did, and he parted smiling and wishing us a fine visit.

At midday we left this idyllic anchorage and steamed around the west side of Île à Vache to our home port for the next four weeks, Port Morgan. Named for the notorious pirate Henry Morgan, it’s conveniently tucked in behind reefs and a headland on the northwest corner of the island. Our anchor was barely set into the bottom before a flotilla of three dugout canoes came alongside manned by grinning ten and twelve-year-old Haitian boys who told us that the mayor would be out soon to check us in. A $5 bill took care of the mayor who informed us that we could take the water taxi to Les Cayes to clear customs officially or we could send someone over to do it for us – no hurry.

No hurry indeed. Like many Haitian villages, Caille Coq – and, for that matter, all of Île à Vache – has no cars or electricity. Without the ambient noise that is subtly pervasive in even rural areas of most First World nations, the peaceful, natural quiet greets the visitor like a calming infusion. Walking the waterfront along palm, mango, and sea grape–shaded trails with the usual entourage of curious but respectful local lads to guide us, we exchanged a smile and polite “bonjour” with everyone we passed. A dozen or more handcrafted, colorfully painted wooden sloops ranging from eighteen to thirty feet lay at anchor while others sailed off with a patchwork of cloth set on crooked spars for a day of fishing in the waters between Île à Vache and the mountainous main island to the north.

Sounds of wood chopping and a caulker’s mallet led us down the beach to three boat builders who were shaping timbers for a new vessel and repairing an old one. The design of these sloops has evolved over the centuries through form, function, and the shapes of the crooks from which the frames are cut with a machete and axe. They are crude but solid and well proportioned, and appear to sail well in most conditions using a sprit mainsail and jib. An oar is the only auxiliary power. Scattered along the sand and mangrove shore are the ubiquitous dugout canoes – man’s earliest conveyance on water, still chopped out

of logs by skillful men with primitive tools.

As we meandered through the village along hard-packed dirt paths, donkeys, goats, pigs, cows, and island dogs greeted us with sleepy eyes and docile tempers. The hip-roofed Haitian houses are small and well built of wood, cement block, locally cut stone, and metal roofs. Separate woven wooden kitchen structures contain cleverly crafted re-bar pot holders over fire pits where homemade charcoal burns in carefully measured quantity for cooking. The yards are planted with fruit trees and small gardens with chickens clucking and ladies washing children and laundry in plastic tubs. Swept clean and neat, there are only the essentials for living – no clutter of “stuff.”

Back aboard at dusk, a yellow dugout headed our way with a smiling Haitian maneuvering his craft with a palm branch in one hand and talking on his cell phone in the other – a confluence of millennium. In his late twenties, Sam Altema, like most of his generation, is looking for a less laborious life than his parents. He’s a good-looking guy with a pleasant smile, fluent command of English, and an entrepreneurial spirit that complements his helpful, friendly nature. After nearly a year of correspondence, it was a pleasure to meet and talk with him about the challenging issues looming over a nation still recovering from the cataclysmic earthquake of 2010.

The next morning we dragged the piles of vacuum-packaged clothing and other stowed items out of Charlotte’s makeshift cargo space and loaded them into a twenty-five-foot utility vessel owned by Sister Flora’s orphanage. The sputtering Yamaha outboard motor pushed us out of Port Morgan and along the north coast several miles to the east to a town named Madame Bernard, the capital of Île à Vache. This bustling harbor surrounded by reefs and shoal water was teeming with activity in many forms. Burdensome forty-five-foot cargo sloops arriving from Les Cayes and other Haitian ports jettisoned their contents on dilapidated piers or directly onshore while fishermen standing waist deep on the reef hauled heavy nets in unison. We loaded our offerings onto wagons and pushed them up the hill, past a shaded parking area for a dozen donkeys laden with market produce and through the gate to the orphanage.

Founded in 1981 by Sister Flora, a French-Canadian Catholic nun, this extraordinary facility has become a paradigm of success that benefits countless orphaned and disabled Haitian children. Since it is not reliably funded, Sister Flora struggles to make ends meet, and our donations from the Vineyard were gratefully dispersed among the seventy-eight needy residents, a third of whom were wheelchair-bound. It doesn’t take a lot to make a big difference in Haiti.

Our conversations with the staff were cut short, however, as we were ushered to our seats in the orphanage abbey for a pre-Christmas mass led by two priests in flowing white robes and seasonally appropriate liturgical accouterments, surrounded by shimmering synthetic Christmas decorations and a black nativity scene. Whenever the priestly ramblings seemed to be droning on excessively, Calix Huguette, a lovely young Haitian woman who was raised in the orphanage, would break into song and lead us all in joyful Creole Christmas carols, in

Patois. This kept the clergy in check and the congregation engaged and awake for an hour and a half during this pleasantly confusing entertainment, occasionally interrupted

by sanctimonious remarks from a portly local dignitary wearing a light green leisure suit and white golf cap.

Without warning, a perspiring Frenchman in full Santa Claus costume came bounding through the door ringing a bell and carrying a large sack over his shoulder. The squeals of delight from the children were a clear signal that the formal part of the service was over. A small present was given to each child until all were quietly clutching their package waiting for the signal to unwrap. Sitting in the midst of these kids with some of them on our laps, we watched as they carefully and patiently opened their yearly gifts, taking great care not to tear the precious paper, and then beamed with gratitude clutching a toy or stuffed animal to their breast. When two large tables piled high with rice, beans, fried chicken, a Christmas cake, and cases of beer and soda rolled into the room, it was time for the feast to begin.

We spent the next few days in Port Morgan doing chores aboard Charlotte and making friends, but at last the time came to fly home to Martha’s Vineyard for work and to celebrate Christmas with our own families, leaving Ian and Charlotte to look after each other. But not for long: shortly after Christmas Pam and I returned to Île à Vache with duffel bags of art supplies, more clothing, and $8,000 in cash raised for the orphanage. Our timing was auspicious, said Sister Flora, since she was unable to make the monthly payroll to her staff, not only at the orphanage, but also at the school and hospital she had founded. At just under five feet tall, this pale-white energetic woman in her seventies has made a significant difference in the lives of so many. The people of Île à Vache revere her.

Vineyarders Roberta Kirn and Boyd Petersen soon joined us aboard Charlotte, and Pam and Roberta would be off to shore each day to visit and work with the children at the community center. Pam nurtured and shared skills with the naturally talented kids in the realm of visual arts, while Roberta did the same musically. Commuting to the orphanage required a two-hour trek each way and the work involved caring for the children’s most basic needs, an emotionally challenging and often difficult task given the large number of disabled children and the minimal professional staff. To decompress, most afternoons we all took the twenty-minute hike to Abaka Beach for a long swim followed by sunset at the nearby hotel where cold drinks and intermittent Internet service were available.

Hiking on Île à Vache is the best way to get around unless you have a donkey at your disposal. This suited our peripatetic nature, and Pam and I had some wonderful excursions through the hilly countryside. One afternoon, with help from an eleven-year-old guide, we headed east from Abaka Beach in search of a small fishing/farming village that I had noticed with the binoculars when we first arrived. Boyd and Ian also had been near this hamlet on one of their surfing expeditions and agreed that we could find it without a donkey or a boat. We wove our way along shore and inland trails, then past a mile-long spectacular beach with a lone bull in residence, and on through fields and valley until we finally saw from a high bluff our desired destination in the distance. This picturesque encampment with smoke rising from charcoal fires and a fleet of lovely local sloops rocking at anchor in their crescent cove was as alluring as it was unattainable, given the rapidly fading daylight. I knew we couldn’t achieve our goal to reach the village on this day.

A short distance away, however, a family farm looked inviting with adults and children scurrying about doing chores before dinner, which was simmering on the outdoor kitchen fire. The occupants greeted us with welcome curiosity as well as smiles and laughter, which we returned. Strong young sons and in-laws were working in the gardens and tending healthy looking livestock in the fields to the east while the women looked after the domestic functions of the compound.

Silhouetted on a knoll against the dimming western sky stood an older man whom I presumed to be the patriarch of the clan. Looking like an Old Testament prophet commanding his people, he held a newly crafted oar in his left hand while he finished shaping the shaft with a tool grasped in his right. A professional boat builder myself, I naturally could not resist walking over to see what sort of plane or spoke shave he was using to create such a well-proportioned and properly tapered auxiliary source of power for his boat.

A kindred spirit, he must have sensed my intentions, for before I even finished wishing him “bonsoir,” he grinned, opened his weathered, calloused hand and proudly showed me the piece of broken glass that served as his tool. When I enthusiastically recounted this story the next morning to Sam, he calmly gazed at me and said, “Yes, that’s Haiti.”

16 comments

16 comments

Comments (16)