When I was a child, I desperately wanted a pet but my mother didn’t like animals, at least not in the house. She thought she could satisfy this desire with a small aquarium and a few guppies. Guppies are not pretty, but they are prolific, and soon I had about fifty little guppies swimming in my aquarium, the small ones dodging the larger ones who tended to eat them if they were hungry. I put a sponge into the aquarium to give the baby guppies a place to hide from their avaricious parents and went off to summer camp for three weeks. I forgot about my pet fish until the weekend parents were allowed to visit and my father, with downcast eyes, described how his attempt to clean my aquarium resulted in the disappearance of all of my baby guppies. He had wrung out the sponge over the sink drain. I wasn’t devastated – it is hard for a child to love a small fish in a bowl of water.

What I really wanted was a dog, and my father must have put some pressure on my mother because one day I came home from school and was greeted by a wildly wriggling, tail-wagging puppy with silky black hair. She was the illegitimate daughter of a pedigreed Irish setter owned by a friend of my mother’s, and I imagine that friend was calling in favors by forcing these unwanted puppies on her pals. Despite my mother’s obvious distaste, I immediately loved this puppy and named her Molly.

But Molly was a wild puppy and I didn’t know how to control or train her. My mother had never had a dog – or any other pet – and insisted Molly be confined to the basement at night and when I wasn’t at home. When I took her for a walk after school she would race wildly around and I would race madly around trying to catch her. Molly never learned to “come” or “sit” or “stay,” which boosted my mother’s disgust. She was constantly muttering, “I knew it wouldn’t work.”

The end result, after a few months, was that one day I came home from school and Molly was gone. I never talked to my mother about why all this happened, partly, I guess, because there was a certain amount of relief on my part that the tension within my family was over.

A couple of years later another dog entered my life. Across the street from my home was a clapboard house with a magnolia tree in the yard. One day returning from school I noticed a large dog tied to the tree with a long rope. The next day he was there again and I approached him. He rose to his feet, tail wagging, so I sat down beside him to stroke his shaggy head. He was as big as a German shepherd, but his crinkly hair was different shades of grey and it fell over his eyes like a child’s bangs. He was unlike any breed of dog I was familiar with, and I was familiar with most of the breeds in the American Kennel Club’s brochure, which I studied with my best friend, June, who had a collie.

One day, while I was sitting by my new dog friend, old Mrs. Schappert came out of her house and invited me to sit on her porch with her. She told me how her nephew had arrived for a short visit accompanied by this large shaggy dog and left a few days later without taking the pet with him. The dog’s name was Wolf, she told me, as if introducing us would further assure our new friendship. She and Mr. Schappert were too old to take care of a dog, she explained, and would I like to – or would I mind – taking him for a walk?

Would I like? Would I mind? She had no idea that she had just answered my prayer to have a dog. And so, although Wolf lived and ate his meals at Mrs. Schappert’s house, in reality, he began to be my dog. And there was no way my mother could object to this arrangement. Gradually even my mother had fewer objections when I begged that he spend the night with me on special occasions – my birthday, Christmas Eve, and whenever I caught her in a good mood and asked.

I eventually went away to college, but Wolf was always there when I came home for weekends or vacation. In my sophomore year I fell in love with a returned veteran from World War II, and at the end of my junior year, dropped out of school to be married. The night before the wedding, I sat outside on the stoop with Wolf. I wanted to bring him to my new home on Martha’s Vineyard, but my soon-to-be husband, like my mother, didn’t want a dog. I cried as I said goodbye to Wolf – I couldn’t imagine what would happen to him when I was no longer in his life. I never saw him again.

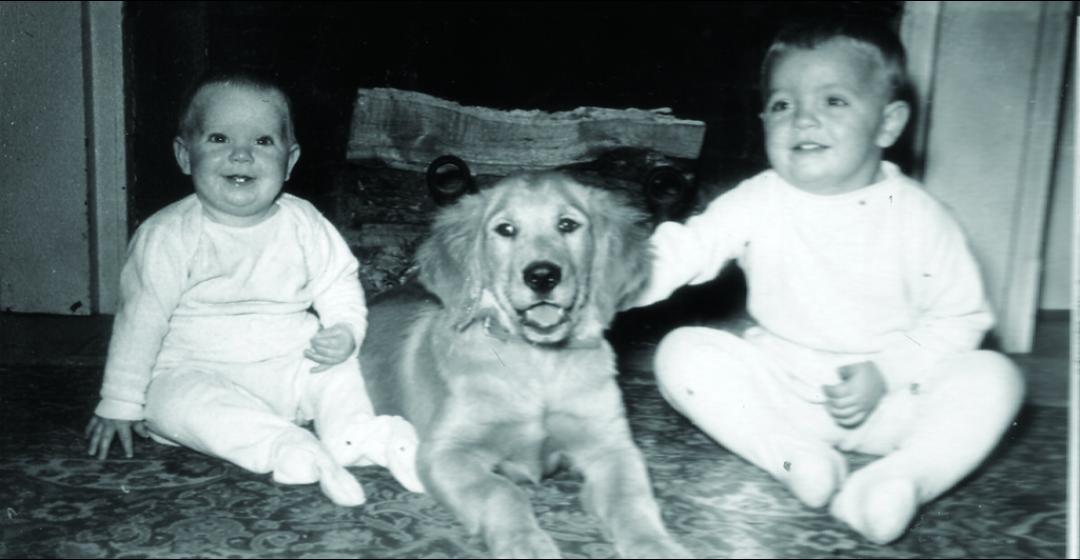

Four years and two babies into my marriage, I finally convinced my husband that owning a dog would not be such a bad thing. The wife of one of our very few celebrities in the early fifties, Max Eastman, was raising a litter of pedigreed golden retriever puppies in Gay Head and offering them for $50 each. Although that was an enormous sum for us in those days, Polly Murphy and I drove up to Gay Head to see the eight-week-old bundles of golden fur and were both immediately entranced – we returned to West Tisbury with our treasures in a large cardboard box.

I named mine Buffy because of the color of his coat, and though he was a sweet pup I had tripled my chores. It was diapers on the human babies, newspapers on the floor for the baby dog, and food for all three. Still, I didn’t want to follow in the footsteps of my mother. I was determined that my children would have pets in their lives as they grew up. And pets they had – from white mice to bay horses. I accepted whatever creature they brought into the house, barring snakes and bats.

At first I did follow my mother’s path and got a goldfish and put it in a bowl. Neither child had expressed the desire to have a pet at that point – Debby was about three at the time – I just assumed that children and pets went together. I’d read that pets instill responsibility in a child, and I knew that they instilled love. Until I realized I’d never heard anyone say, “I love my goldfish.”

When I became pregnant with my second daughter, I thought it might be helpful to explain the whole birthing process to Jack and Debby by acquiring a cat that would produce a litter of kittens, preferably between nap time and bed time, in a place where the children could observe the process. I got a young calico cat, a color scheme that almost always indicated a female cat, and sure enough after a few weeks loose outside, she became pregnant. When it was apparent that she was ready to give birth, I shut her in the enclosed porch and called the children. It worked. They watched entranced as six tiny, blind kittens were ejected onto the blanket I had laid out. When my daughter Sarah was born a few months later, they were disappointed that I produced only one baby. Where were the other five?

The children loved the kittens, but I was not a cat person. I was a dog person. After Muffy served her purpose of teaching the facts of life and I had taken her six kittens to the local summer fair in a basket and given them away, she was killed by a car in front of our house.

The lessons of death came quickly upon the heels of the “facts of life” lesson, but were not as interesting to the children. Impatiently they listened to my few words eulogizing Muffy and her short life as we prepared her burial site. Then they ran away to play with their friends who had been invited over for lunch and a funeral.

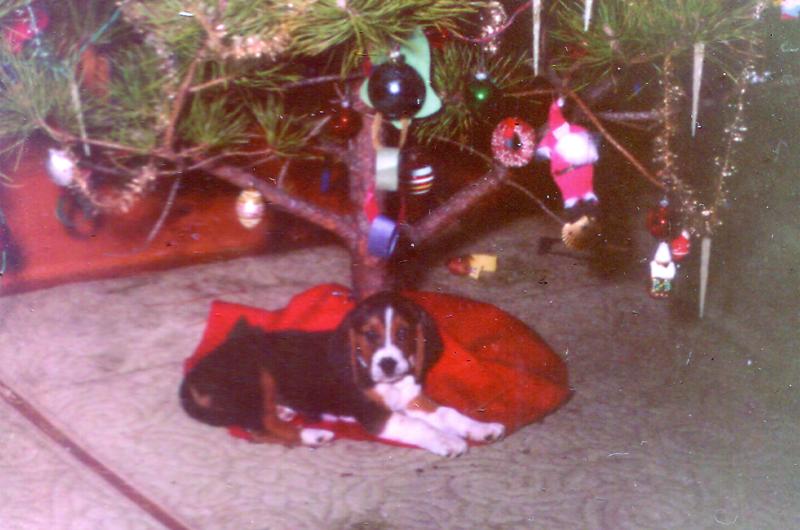

The children began to choose their own pets: ducklings whose mother walked them up from the pond in front of our house for some bread tidbits, painted turtles caught in the pond, kept for a few days, and then returned to the water. In 1960, with Buffy nearing the end of his life, we gave Jack a puppy for Christmas. Tippy was a mixed breed with the mix being mostly beagle, and with leash laws years in the future, he followed his hunting instincts at will all over West Tisbury. Finally one day he ran off and joined a few other dogs that were harassing the sheep at Arnie Fischer’s farm. We had to get him out of farm country so we gave him to a rabbit hunter in Vineyard Haven, and I hope he lived happily ever after – but I don’t know.

Lindy came next and looked much like Tippy, and when Jack entered him in the dog show at the Agricultural Fair, he won not only best crossbreed, but also a special prize of $5 given by the Vineyard Gazette. But three months later Lindy was run over by a car. We tried again with another hound – this one was more basset hound than beagle – he had a solid body with short legs. Jack named him after an Italian racing car that he admired: Bugatti. Unfortunately, Bugatti shared Lindy’s fate and was hit by a car.

My one cat experience ended when Muffy was run over by a car, and now my dog experiences were ending the same way. Then somewhere Debby got the idea that she wanted a mouse for a pet. Well, the chances were slim that a mouse would get killed by a car – by a cat, perhaps, but I wasn’t planning to get another cat. So I got Debby a white mouse with a cage and an exercise wheel. In the meantime, old Buffy was very tolerant of these new animals coming to live with us. They came and went so frequently that he never really bonded with any of them.

For a while we had a collection of butterflies in the house. Well, they weren’t butterflies when we brought them into the house. Sarah and I collected the green and yellow caterpillars that turned into monarch butterflies. We found one on the leaves of the many milkweed plants, their favorite food, that grew in our lower field. We put several milkweed branches in a mason jar and introduced the captured caterpillar to his new home.

When he was quite satiated with milkweed leaves, he twisted and turned his body while the jade green chrysalis worked its way up his body until what had been a caterpillar looked like a jewel hanging by a thread from the milkweed twig. Radiant golden dots appeared on the green chrysalis, emphasizing the beauty of this creature.

Sarah counted the days as the caterpillar changed into another being that would drink instead of eat, fly instead of crawl, be admired instead of ignored. He did it in secret and emerged after fourteen days, his wings hanging limply as he struggled to get out of the self-made bag he had been in, yet holding on to it with his new and longer legs lest he drop to the ground before he was ready. When his wings were spread and he seemed ready to take up his new life, we carried him outside, bid him Godspeed, and watched him fly off.

One time when Sarah had several caterpillars in her room at once, they did escape, and we found them hanging in different places they had chosen for their transformation – one was hanging from a handle on her dresser, another from a slat on her venetian blind, and a third had chosen her earring holder. It looked so much like another beautiful earring that we tried to put a second caterpillar next to it to make a pair, but it didn’t like the location and moved to a twig.

I thought of a caterpillar’s transformation almost as a reincarnation and wondered about the birth and death of human beings. An egg is planted, a fetus is formed, and a human baby emerges, lives, and dies – to become what?

Two rabbits joined our family about the time Sarah was ten years old. I can’t remember how she got the first one, but I certainly remember how the second one came to us. Sarah named her first bunny Chocolate for his coloring, and he was small and gentle and pretty and quite

lovable. My husband Johnny set up a cage for him outside, and he quickly took up the space the run-over cat and dogs had occupied in our hearts. But poor bunny – he never really bonded with any of us humans the way a cat or dog will. He needed another bunny to play with. One of us – it wasn’t Johnny, I know – must have sent up a prayer for a companion, because one late fall night as I was sitting in the living room reading, with Jack at the coffee table doing his homework, we heard scratching at our living room door.

There was a granite rock about three feet long that served as a step up to the door, and when I looked out the glass panes I saw a rabbit on the step. It seemed to want to come in. It didn’t look like a wild rabbit, but rather more like Chocolate. I sent Jack out the kitchen door to sneak up on the rabbit, and he caught him. I think he wanted to be caught, as he was domestic. After we had canvassed the neighborhood and could find no one who was missing a rabbit, Sarah named him Licorice and he joined Chocolate in the cage out in the yard.

Buffy died in the early sixties and left a big hole in my heart. At the time I was attending Boston University and staying with a friend in Cambridge two nights a week. In May, on my last day in the city, I returned home with a golden retriever in a cardboard box. I named him Treve, and for many years he retrieved all the ducks and geese that Johnny shot on Tisbury Great Pond.

One year Johnny brought down a Canada goose with a shot that shattered her wing but didn’t kill her. He took her home and built an enclosure that was half in the water of the pond and half on land, and although he had to cut the damaged wing off because it was too shattered to mend, the goose thrived. We fed her and when she was accustomed to us and her surroundings, Johnny let her loose in the pond.

The children named her (or possibly him) Andrea, for what reason I never did figure out, and over the winter she became very tame. Even Treve learned that she was not to be retrieved, but considered as part of the family. I would sit on the bench on the shore of the water feeding Andrea while Treve sat next to me, and they played their parts peacefully. Fall came, and another hunting season with it, and one day a single goose scaled down into the pond with a damaged wing. The word must have gotten out that Looks Pond was a good place to go if a goose was wounded, for Gus (as the kids called him, hoping that he would become Andrea’s mate and they would live happily ever after together on our pond) settled in for the winter – and we had a pair. But we didn’t know if we had a pair of male geese or a pair of female geese, or a couple. We just had to wait and see.

Later, as spring approached, I was awakened one morning by loud honking from the pond. I rose and witnessed a heartbreaking scene. Over the winter Gus’s broken wing had mended and he had felt the call to migrate. He was trying out his wings, and he urged Andrea to fly with him. As he took off to circle the pond, Andrea tried to follow him, but with only one wing to flap, she merely went around in circles on the surface of the water. Gus would return and land beside her, encouraging her in his goose talk to try again. She tried hard, but only succeeded in swimming in circles, unable to lift herself into the air with one wing. After several attempts to help her, Gus made one last circle over the water – and then left. Andrea was again alone.

The next winter was a harsh one, and the pond froze over completely, leaving Andrea no alternative but to go down the brook to find open water. Some weeks later we found her body near where the brook ran under State Road. Someone had shot her.

Sarah, from a young age, loved horses more than any other animal. Every chance she got, she rode on horses and ponies borrowed from her friends who owned them. When she was twelve, in the summer of 1968, I was offered a free horse from the people who owned Featherstone Farm, which at the time was still a farm. I didn’t tell Sarah at first, because my husband Johnny disliked horses even more than he didn’t care for bunnies and cats and white mice. He was very fond of Sarah, however, and a twelve-year-old bay gelding named Hot Toddy moved into our old barn on August 31. Sarah was ecstatic.

Toddy broke loose and ran away three times the first week we had him. But gradually he seemed to realize that he had a new home and a caregiver who loved him, and from then on he was never any trouble again. Although I had ridden horses as a young girl, it had always been at a nearby commercial stable. Sarah taught me how to properly saddle Toddy, tighten his girth, and force open his mouth to insert the bit before I settled the bridle over his head. Then I was able to ride him when Sarah was in school.

Sarah joined a 4-H horse group and began competing in local horse shows. She spent all her weekends and after-school time caring for and riding Toddy. After two years she was offered another horse, an eight-year-old thoroughbred named Day Dream. Sarah had gained a reputation as a good horsewoman, and we agreed that she would be able to handle a second horse. Day Dream was taller than Toddy, black instead of bay, and a handsome riding horse. But my heart belonged to Toddy. I didn’t trust Dream. She ignited my disapproval when every afternoon she chased Toddy away from his pail of oats until she had finished eating hers.

During her high school years Sarah’s room became decorated with yellow ribbons, red ribbons, and many blue ribbons, as well as a number of trophy cups. She used Dream in jumping classes and classes that required high-stepping elegance, while Toddy became a champion in the class called “break and out,” in which the judge would shout out a gait and the horse that obeyed every command immediately was the winner.

Toddy became ill during Sarah’s senior year and since the Island in the mid-seventies had no large animal vet, she had to wait for the monthly visit of the one from off-Island. After examining Toddy he said he would need a urine sample, and gave Sarah a small bottle that she could mail to him. We didn’t think to ask him how to get a urine sample from a horse.

That next weekend Sarah followed Toddy around as he grazed in his pasture. She had a bucket with her, and every time he stopped to relieve himself, she would position it, but as soon as he heard the ping in the pail, he would bolt, almost knocking her over. Although Toddy liked being outdoors better than being in his stall, she decided that the only way to get him to stand still was to confine him in the barn. She closed him in one night, and later joined him with her sleeping bag, her pillow, and a pail. At around midnight I heard her come back into the house. She had achieved her goal – just enough urine for the small bottle. But the test failed to tell the vet what was the matter with Toddy.

He continued to decline and soon Sarah’s graduation was upon us. She would be gone and I couldn’t deal with a sick horse by myself. Dream went to a new owner, and we made the decision to put Toddy down.

I’d had to put down two dogs, but a horse was a whole new horror. Sarah couldn’t face it and asked me to make the arrangements. I didn’t know where to begin, but it had to be done before my family arrived for Sarah’s graduation. I called a few friends who were horse owners and Marjorie Manter offered to oversee it – she realized at once how difficult it would be for us.

To put a horse down one needs a backhoe and a man with a shovel, to be coordinated with the presence of a vet and someone to lead the horse to the large hole, after it has been dug. We chose a plot on the edge of Toddy’s pasture. Our beloved horse would be led to stand next to the hole. He would be given a lethal injection by the vet and then fall into his grave.

We were not there. Sarah was in school, Johnny was teaching at the high school, and I was teaching at the Edgartown School. That afternoon I walked to Toddy’s pasture and saw a large mound of dirt. On top of it lay six long-stemmed pink roses – Sarah had been by and gone before me. When I returned to my kitchen I found six more roses and a note from Sarah thanking me.

I collapsed onto the back stoop outside the kitchen door – and I sobbed. I cried for Toddy and I cried for Sarah and I cried because my third and last child was leaving home. I was forty-seven years old. My whole life was changing and I felt that my days of being a mother were over. I cried until I had no tears left.

In September I drove Sarah to college in Ohio, and returned to begin my adjustment to a home without children or pets. After a childhood of yearning for a pet, I had supplied my own children with goldfish, turtles, rabbits, white mice, ducklings, monarch butterflies, a Canada goose, a cat and kittens, three dogs, and two horses. Through all of those years I remained a dog person, a golden retriever person – but I failed to pass on my great love for dogs. My children grew up and left home to live their own lives – as cat people.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)