Standing in his Chilmark Chandlery shop in Menemsha, surrounded by Poole’s Fish hats and

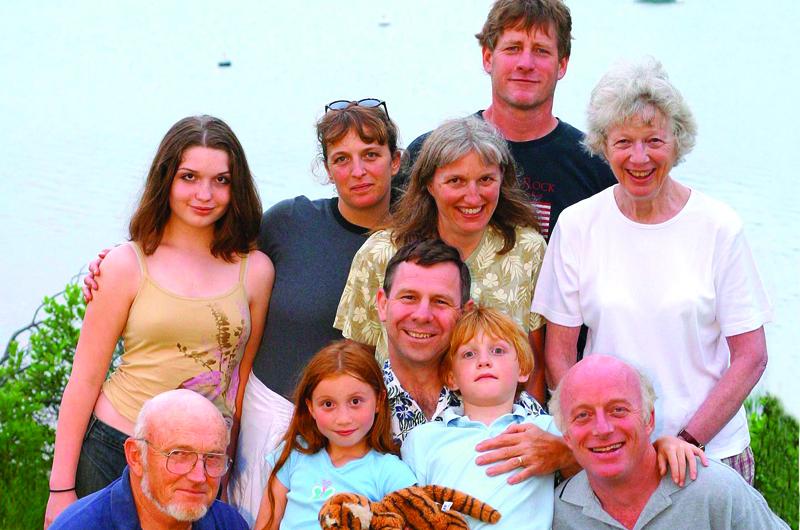

T-shirts, wholesale ropes, and other commercial fishing gear, Everett Poole looks far younger than his eighty-four years. What’s more, his current daily schedule makes the average person look like a couch potato: besides running the Chandlery most afternoons, there are his family’s properties on Nashaquitsa Pond and in Menemsha to take care of, fishing or scalloping to be done (depending on the season), and a number of lobster pots – he refuses to say how many – to tend. He recently finished rebuilding a scallop boat. Though nowadays he might stop for lunch and the occasional nap, for Poole, this is slow. Retirement speed. “I run an old men’s club now,” he says of the Chandlery. “They just come in and hang around.”

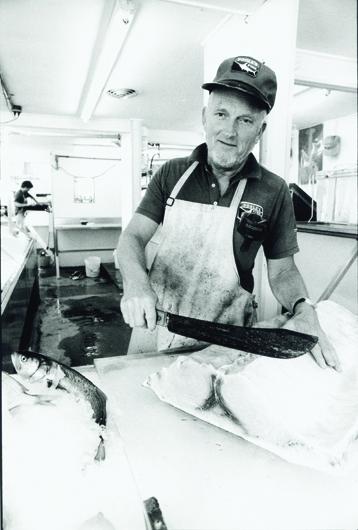

Poole, who was born on the Island in 1930 and grew up on the Menemsha Crossroad, is a Chilmark icon. He was first elected town moderator some thirty-eight years ago. He owned Poole’s Fish Inc., better known as Poole’s fish market, for fifty-one years and the Menemsha Texaco gas station for ten years, and he still runs the Chandlery. Both sides of his family have been here since the 1700s. With his snow-white beard and brown pipe, he is almost a town father of sorts. But he is also happy to report that he has not always been embraced or even supported by his hometown.

First, there was the time when he was thrown off the waterfront. In 1947 he was buying and selling so much fish that town selectmen attempted to have his business moved off the Menemsha Bulkhead, as the land between the Texaco station and the bridge over the creek is known. The customers followed their favorite fishmonger and, Poole says with a smile, “Ironically, the same selectman who asked me to move out asked me to bring my business back seven years later!”

And then there was the time when one of his neighbors tried to prove that he didn’t really live in Chilmark because, as he says, “There was an element in town who had an eye on my business.” He laughs about this now too. It started when two of his children, Joan and Donald, were ready to go to school.

“In Chilmark, we lived two-and-a-half miles from the closest kids and my wife was going nuts,” he says between puffs of pipe smoke. “My kids were live wires, and she wanted to be closer to other families. Of course, I didn’t want to move, but Jini kept looking for a place to rent. One night – it was New Year’s Eve, actually – I was running the gas station and Jini called and said, ‘If you want supper tonight, come to Edgartown.’”

She had rented a house for the family on Mullen Way in Edgartown, but Poole could only spend four months a year down-Island, lest he lose the Chilmark residency required for his claim on the bulkhead. (The bulkhead was built as part of Menemsha’s restoration after the hurricane of 1938 and was divided into small lots, one of which was awarded to Everett’s father, Donald, who had lost a fishing shack on the harbor in the hurricane.)

“It was awful,” Poole says. “They’d follow me home, see if there were lights on in the house, sometimes knock on the door just to see if I was really there. I’d move to Edgartown Halloween night and be back here in Chilmark by the first of March.”

Poole checks the Chandlery’s answering machine and heads to a less cluttered corner of the shop where there are three ramshackle chairs. He grabs a piece of browned, dried foam atop a giant spool that serves as a makeshift table and tosses it onto the seat of a chair fashioned out of plywood. Then he sits down to light his pipe.

“I’ve smoked for too long. I quit for six years, but,” he laughs, lights a match, and inhales.

Everett Poole’s memories go back even further than the time a half a century ago that his neighbor tried to prove he wasn’t a “real” Chilmarker, of course. They go back to childhood on an Island that one can barely even imagine now, when the town’s dirt roads had no signs. There were vast woodlands, untouched fields, and waters so rich with fish that he remembers his father regularly catching thousands of pounds of swordfish. People would set nets just off the Menemsha Bight and find them filled every day. A time when his grandfather caught a 250-pound swordfish with just his hands and a jackknife.

Life was simple: everyone worked. Poole’s mother, Dorothy, taught at the Menemsha School. His father, Donald, was a fisherman. Gardening, canning vegetables and fruits, hunting, and fishing were all part of the fabric of everyday living. Growing up on the Menemsha Crossroad in a house with no electricity, where water was pumped by hand, one of Poole’s daily chores was to fill up the three kerosene stoves used to heat the house – one in the kitchen, one in the living room, and one in the back room where his grandmother lived. “She lived with us for about twenty-five years, I guess,” he said. Those kerosene cans were pretty heavy when I was in first and second grade.”

After school, he’d refill the cans, bring in firewood, take the garbage out, feed the chickens, pick up the eggs. “My chores were a full-time after-school project. I didn’t have time to get into trouble,” he recalls. “Kids couldn’t get into trouble in those days. Now you have electricity that does everything and kids have time on their hands.”

Whenever he did have free time, he took on odd jobs. A lot of them, as it turned out. It started with “mowing other people’s lawns, helping out down in the harbor,” to which he soon added a paper route (the equivalent of three paper routes) and putting the Sunday paper together on Saturday evenings. When he was ten he stocked shelves after school and on weekends at the Chilmark store. At eleven he worked there for the entire summer. “I had to be there at quarter to six,” he says. “There were gas pumps there then. The mail went out at six a.m. It was called a six-to-six job, but you didn’t get through till quarter past six at night. Had to eat your lunch on the run. I earned a dollar a day and was damn lucky to have a job. I was the only kid that year that had full-time work. It was 1942. The world was a mess.”

The one job young Poole didn’t have was working on his father’s boat. When he was very young, he did fish with his dad, but “He got mad at me. I still don’t know why or what I did. And then my dad said, ‘Boy, there is no place for relatives on this vessel.’ It was the middle of July. Everyone else already had their fishing crew, so that’s when I started peddling fish.”

It was the summer of 1944, Poole was just thirteen, but he struck out on his own, selling the extra fish from Donald Campbell’s fish trap to “anybody who was hungry.” Every day, after his chores and paper routes or before them, he rowed out to the trap in Vineyard Sound, picked out fish, and sold them from a baby carriage. “It was a long push to Quitsa and back,” he recalls, and after a month or so of working at this pace, he got pneumonia. Nonetheless, the business was successful enough that the following year his father let him set up shop on the bulkhead and, as already mentioned, by 1947, the selectmen were agitating to get him closed down.

Poole’s father encouraged his forays into the fish business, but his mother had other plans. “She didn’t want to teach me,” Poole says of his schoolteacher mother, who relinquished her job when her own children began to attend the school. She didn’t mind being his teacher at the Chilmark Church, though, where she was the superintendent of the Sunday School. “I had perfect attendance at Sunday School,” he says. “Every Sunday. And I was also in charge of pumping the church’s organ.”

She was delighted, therefore, when Poole enrolled at the University of Rhode Island to study engineering. “I thought that’s what I wanted to do,” he says. “I had had a summer job building steel yachts in West Haven, Connecticut, one summer, earning $38 a week. I was the talk of the town then – that was huge money. But when I got to school, I quickly learned that it wasn’t for me so I switched to a business degree.” From there, he was drafted into the Coast Guard. After attending officer training school in New London, Connecticut, he skippered cutters in Florida and Georgia. Eventually, he was assigned to the search-and-rescue office in Boston and tasked with setting up a training program for lifeboat personnel.

The Coast Guard motto, which Poole says is his motto too, is Semper Paratus (Always Ready). While he loved the Coast Guard and had been ready to teach, he was also ready to start his adult life back on the Vineyard. In typical fashion, he didn’t waste much time once he got home. Between 1955 and 1958, he met and married Virginia Fedor, built the bones of what would become Poole’s fish market on the bulkhead, bought the gas station at the other end of the bulkhead, became the Menemsha harbor master, built a house – the house he still lives in – on an outcropping overlooking Quitsa Pond, and became a father.

“I dug the well in this house, which is in the basement, with a shovel,” he says, sitting at his kitchen table that looks out over a corner of one of Quitsa’s marshlands, “Jini’s grandfather came over to inspect the house and asked to go down to the cellar. He went down and said, “’This is a good house.’ When he got home he reported to Jini’s family that I’d built a good house. That I’d do well.”

With a nearly 360-degree water view, the location is spectacular. Over the years, it’s become a prized location for the very wealthy’s second or third homes. But the way Poole tells the story of how he came to own it fits in with his complicated history with his fellow townspeople. “This place was named Bumblebee Hill because it was infested with bees. In the old days, this was where trap fisherman used to lay out their pond nets to dry. In those days, they [the nets] were cotton and sisal, so they’d have to let them dry, pick all of the grass off of them, and then tar them up. I didn’t want to build a house here, but no one else would sell land to me.”

“In the ’40s and ’50s no one saw a need to sell their land. It was a Yankee tradition to hold on to your land,” he explains diplomatically. But his eyes suggest there is more to this story that he will not tell.

Even with the new house built, it was a good thing that Jini loved him as much as he loved her. “I ran a scallop shed,” he remembers of their first year of marriage. “I filled my shop with benches and hired women from Gay Head to open scallops. I used the women because they had nimble fingers. Because you take a guy who has been out scalloping and hauling dredges and freezing, versus a girl who has come from the kitchen at home, the girl is going to do a better job. God, it was hilarious that gang. Poor Jini. She was pregnant with Joan and had terrible morning sickness. We couldn’t start scalloping until 8 a.m. in Chilmark. So I would come down, open the place up, ’cause the fisherman all kept their foul-weather gear in my shop to keep it warm. Then she would come down about 7:30 and I would head out with my father to get my limit of scallops. She would sit in the shed, monitoring the women, settling the rows because sometimes they got to fighting. The poor girl. We heated the place with a kerosene stove and there were scallops everywhere. The place stank. She drank Cokes all the time. What a way to start your marriage.”

Two years later, their second child, Donald, was born, followed in 1967 by daughter Katharine. Poole now had three young children and three businesses, having opened the Chilmark Chandlery to supply the men he bought fish from with rope and other supplies. But it still wasn’t enough. As a concession to his doctor, who told him to scale back for the sake of his health, he sold the gas station, but also opened branches of the fish market in Oak Bluffs and eventually Edgartown and Vineyard Haven. With a partner he also launched Menemsha Bites, Inc., which focused on shipping frozen fish off-Island.

By now even his old rivals on the waterfront had given up trying to push him out, and in the ’70s and ’80s Poole’s fish market and the Chilmark Chandlery thrived. He shipped lobsters to places as far away as Rome, and rope from the Chandlery to Alaska. Back in the ’40s he had installed lobster tanks in his market. Now he continued to lead his field, introducing vacuum packing, a first for the fish industry. He says, “I did it because I wanted to increase the sell-by date for other outlets that we serviced.”

In 1995, Poole sold the fish market to his son, Donald, who had long worked at the market with his father. But the arrangement didn’t thrive. In 2004, Stanley Larsen and his wife, Lanette, took over the location and changed the name to Menemsha Fish Market.

“At one point, Donald’s mother and I insisted that he work for someone else because he’d always worked for me. So he worked for someone else for a year. But he came back. He said he liked working for me,” he says. “Anyway, after Poole’s was Donald’s own thing to do, it wasn’t so much fun for him. I worked for Donald for five years, but…it just didn’t work out.”

But Everett Poole didn’t unlist his business number, he’s quick to add. “I’m not yet retired.”

In 2008, Jini Poole died after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. “We were married for fifty-one years,” he pauses, “Three months short of fifty-one years. I was supposed to die first. That’s the way it’s figured. You never know.” Beyond being the mother of his three children, Jini was an advocate for theater, wrote for the Vineyard Gazette, and was a champion of hospice. “Her only failing,” Poole says, “was that she was a Democrat.”

He smiles. As the Chilmark town moderator since his election in 1977, Poole relishes being apolitical. “Being town moderator involves not getting involved,” he says. “It involves being impartial. One year I didn’t even bother to submit papers and I still got elected.” He pauses. “Though sometimes I wish I could be on the floor raising hell with the rest of them.”

It’s easy to imagine that even at eighty-four years old Poole would have no trouble keeping up with the best of his townspeople. He remains incredibly partial to the Island and fears that it will continue to be what he calls “an in spot” for the elite. If asked what he’d like to see for his Island’s future, the man who once had to prove he was a legitimate resident says, “Maybe two things: sink the ferries and ground the planes.” He sighs, “But in the meantime, I think it’s time for me to head home for lunch.”

But not before one last bowl of tobacco. “Dianne doesn’t let me smoke in the house,” he says and lights up.

Dianne is Dianne Smith, Poole’s “mistress.” “I’ve known Dianne for at least forty years,” he says. “She and Jini were friends and our daughters Jennifer [Jarrell] and Katharine were great friends. Dianne came back from Kenya, maybe three years after Jini passed, and saved me from having to fend off all the women.”

He laughs again and continues, “Anyway, we were at Conrad and Jane Neumann’s fiftieth wedding anniversary at the house behind the church and one of the guests asked Dianne, ‘What are you to him?’ pointing to me. She said, ‘I’m his mistress.’ His jaw dropped and he just walked away. She lives with me now. At my age, you don’t have to worry about the sin part.

“And, honestly, at my age, I don’t worry too much about what anyone thinks,” he says, as if his age had anything to do with it.

7 comments

7 comments

Comments (7)