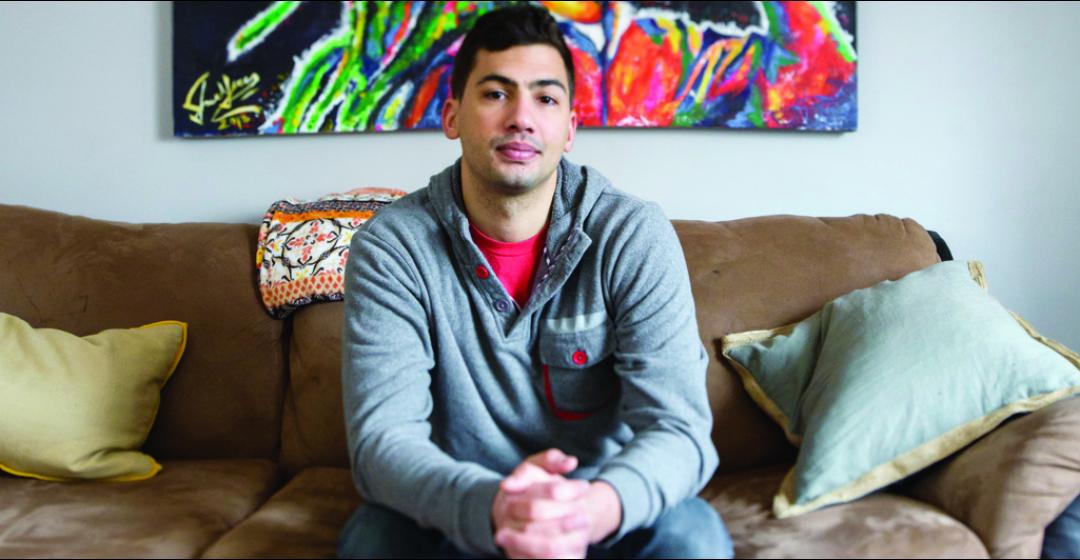

Adam Rebello is home – for now.

Born on the Island in 1985, he’s never spent a summer anywhere else. But winters are usually a different story: since high school, he has often left to find work – in Florida, Colorado, Boston – usually in the restaurant business. On-Island, he spent nine years at Farm Neck Golf Club, working his way up to become his mother Mia’s assistant manager in charge of the food and bar business, and recently left a job as manager of the new Edgartown restaurant, Rockfish.

One gray, cold morning earlier this year, as snow pinwheeled up North Water Street outside, he sat at a window table and considered the challenges his contemporaries face sustaining a life on the Vineyard. Many of the friends he grew up with aren’t so lucky, living and working off-Island, some of them unable to afford to return.

“I think all Islanders, eventually, they want to come back. I just don’t feel the Island lets them,” he said. “It’s very difficult to be born here, raised here, spend your whole life here until you are a certain age and then, ‘I can’t afford it.’”

Call it the yin and yang of the year-round Vineyard experience, a duality that has directly or indirectly affected almost every segment of the Island population. The distinctive character, the community, and the breathtaking scenery of the place came up time after time in conversations with people who were born, or graduated, or were married here thirty years ago. But they also spoke of the financial sacrifices involved in choosing to live here.

Ray LaPorte, an investment and financial advisor who moved to the Island with his wife Bernadette in 1987, summed it up succinctly for the many Islanders who make that choice: “As I say to so many people, it’s a great place to live and raise a family but it’s a god-awful place to make a living,” he says. “Also, it’s a fabulous place to retire but you have to have way more [resources] than most people because the cost of living is 30 percent more.”

In the three decades since 1985, the Vineyard has confronted a thicket of challenges: preserving the environment, improving the schools, diversifying the local economy, addressing the health and safety of Island youth. These are not unlike the challenges facing many small towns and rural communities off-Island, and many Islanders who experienced important rites of passage in 1985 felt that the Vineyard has made admirable strides on some fronts. These included protecting open space and a rural character, building infrastructure – a new hospital, airport, libraries, schools, the YMCA – and providing a cultural vitality extending past the shoulder seasons.

But what emerged in high relief was that a segment of the population – most important, those between 25 and 44 years old – are closely weighing the costs versus the liabilities of living on the Island year round. They are looking again at the seemingly unlimited rise in the price of housing and the relatively limited employment opportunities – and looking elsewhere.

“I think it is difficult to really make a living and have an opportunity to have a family and buy a house,” says Rebello. “That’s probably one of the hardest parts: People are leaving. Men my age who can buy a house in Falmouth, who can go onto the Cape and get something for half the price, are doing that.”

“How can a young family save money and get ahead of the game? You can’t. Especially if you have a couple of children and your family’s here. You want to stay here. Why not go to the Cape, or just outside Boston?”

The Island saw many things in 1985, including the death of the longtime editor of the Vineyard Gazette, Henry Beetle Hough, who, ever aware of the rhythms of newspapering, died an hour before the paper’s page one deadline on a Thursday afternoon in early June. For decades Hough had been the Vineyard’s foremost ink-stained chronicler, an icon who rhapsodized about its qualities, its people, its seasons, its natural wonders. Unafraid of using his soapbox, he inveighed relentlessly against forces – including unchecked growth and development – that he felt undercut the Island’s already fragile beauty and character. And he put his money where his mouth was: when Sheriff’s Meadow, a field near his Edgartown home, was threatened, he and his wife Elizabeth Bowie Hough ponied up to buy it and protect it, launching Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation, which since 1959 has protected nearly 3,000 vulnerable acres.

By 1985, Hough had seen an Island with little or no zoning evolve and adopt local planning restrictions in the early 1970s. He had witnessed – and championed – the creation of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission by the legislature in 1974, intended, among other things, to provide careful scrutiny to developments of regional impact. Yet he remained worried for the future of the Island he loved. A week before his death he told this magazine, in an interview that ran in the inaugural issue, that he feared “the suffocation or the loss through one channel or another of the old values which were all important to the old people,” and warned of the “rapid growth program which we seem to be following willy nilly without choice.”

Hough was not alone. After many decades of relatively flat population growth following the First World War, in the 1970s the year-round population of the Island began to expand rapidly and by the mid-1980s the signs of change were everywhere. In West Tisbury, residents openly fretted that growth was destroying the town’s rural character, the same rural character that had attracted the first wave of “washashores” a decade before. A decidedly sleepy hamlet that once shut down after Labor Day now kept town hall routinely open for business in the off-season. The school, built in 1975 for 163 students, already exceeded its original capacity by 25 percent. And submitted for consideration that same year was a 200-acre, 86-lot subdivision proposed along the west side of Deep Bottom Cove.

“We talk about it so much now. We just say, ‘what are we going to do?’” a member of the town’s planning board, Stephen Bryant, told a Gazette reporter in 1985. “By God, we better get going and do something…”

And West Tisbury was no outlier. Islandwide, building permits for single-family houses were spiking, reaching 619 in 1986 and never approaching that level again. (In 2013, the latest year available, there were 106 such permits issued.)

Chad Metell, who graduated from the high school in 1985, recalls how different the mid-1980s were from earlier years, when he’d ride his bike through neighborhoods and see an occasional new house under construction. By high school, when he could drive? “‘Oh, there’s a new house. There’s a new house. There’s a mansion!’”

It was against this backdrop that perhaps the greatest tool to preserve and protect access to natural land all over the Island was embraced. Hough missed seeing it by a matter of months, but in 1985 and 1986 the Massachusetts legislature and local voters acted to create the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank, which exacts a 2 percent transfer fee – a tax, its detractors say – on most land transactions to fund acquisitions and other protections. From 1986 through last June, that fee has yielded more than $183 million and underwritten the protection of more than 3,100 acres – or about 5 percent of the Island.

“What that’s done is not just preserve but open up for public access places that you could never – ever – go before,” says Ronald H. Rappaport, an Island native and legal counsel to the land bank and to five of the Vineyard’s towns.

That includes access to the beach under the cliffs at Gay Head, and other gems once less widely known that have come into the public’s consciousness: Sepiessa Point on Tisbury Great Pond, Great Rock Bight on Vineyard Sound, Pecoy Point on Sengekontacket Pond. Not to mention the barrier beaches. “All the barrier beaches had become completely privatized by the time the land bank was formed,” says its executive director, James Lengyel. “And now each one has a public beach.”

“The land bank has had the effect of making the Island seem bigger, I believe, because places that had been, in the sixties, acknowledged to be everyone’s to enjoy were shut down by the seventies,” he says. “One of the goals of the voters clearly was for the land bank to start buying back that which had been lost.”

Add to that the efforts of the various private conservation groups and state and town conservation efforts, and a rough estimate of the Vineyard under protection has risen from about one-third of the Island in 1985 to close to 40 percent today. This is not to say there aren’t still large and vulnerable swaths of the Island that should be better protected and more accessible to the public. And it’s certainly not to say that the pace of development over the past thirty years has not fundamentally changed the Vineyard: while the amount of conserved and protected land rose by 6 percent or so over the period, the number of houses on the Island nearly doubled, to more than 17,100 units.

When asked to assess efforts since 1985, Lengyel lets out a sigh. If only the land bank had existed ten years earlier, he says, but then, what if it hadn’t been created until ten years later? “I can drive around this Island, look at the land bank properties and know – my number is 80 percent – that they’d be developed by now,” he says. “They were ripe for development. Sometimes the land bank bought them from developers themselves.”

“Certainly a lot had been accomplished by 1985 here, but there were still big chunks, whole cloth. And so what has happened, I think from 1985 to the present, Martha’s Vineyard has now arrived to a place where we are now able to focus on plugging holes.”

They are vital holes, to be sure. Parcels that can complete the cross-Island trails, either north-south or east-west, and the occasional marquee property like the thirty-odd acres the descendants of Henry Beetle Hough recently donated to the Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation to expand the magnificent Cedar Tree Neck Sanctuary. There is plenty still to do, but suffice it to say that conservationists would much rather be plugging holes than piling sandbags against the flood tide of development of the mid-1980s.

Troy Harris finally came home.

After graduating from Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School in 1985, she spent most of the next three decades off-Island – in college and graduate school, in the Peace Corps, in private schools teaching all over Europe, and, more recently, in Denmark, where she did administrative work for the World Health Organization.

Then last summer, she and her husband, Max, decided it was time to move to the Vineyard to be near her folks in Oak Bluffs, where Troy, her two brothers, and a sister grew up.

“Great community, beautiful place,” she said, flashing a smile as she recalled her early years on the Island. “Oh, it [was] a little boring in the winter, but it was wonderful, too, and such a safe, warm, welcoming place to grow up.”

Troy and Max quickly found jobs here – she at the high school, he at the West Tisbury School – as their daughter Madeleine, 11, and son Gabriel, 6, began settling into their new home.

At the YMCA one evening earlier this year, Troy talked about her expectations after being away so long. The sense of community was as strong as ever, and the Island’s startling natural beauty was intact. Even the cost of living here wasn’t a total surprise – they had owned a flat in Copenhagen, and thus knew a thing or two about living in a land of pricey real estate. Even so...

“It’s really shocking,” she said. “I’m living with my parents. When we were planning to come back, I was thinking it would be a year or two [before] we’d get ourselves settled, we’d get good jobs and then get our own place. And now I’m thinking it will be a longer process.”

A generation after the great conservation battles that dominated public discourse in the 1970s and 1980s, the high cost of housing, for renters and homeowners alike, has become such a cliché that the eyes glaze over at the very mention of it. Until you consider the numbers that illustrate the troubling gap between Islanders’ typical income levels and the housing prices they face. Consider this: the median price of a single-family, owner-occupied home on Martha’s Vineyard is double that of the statewide median, according to 2013 census data. At more than $665,000, the center point in Dukes County home prices is surpassed only by Nantucket (at $929,700) among Massachusetts counties. Statewide, the median is $330,100.

The median household income on the Island, meanwhile, is about $66,300, which is near the statewide level, but is far below a typical household’s ability to service a thirty-year mortgage with a 20 percent down payment at the median price. A 2013 Island housing needs assessment estimated that a family needs more than $225,000 for that “mid-priced” Vineyard home to be affordable. The not unexpected result is that Islanders spend more of their income on housing than their counterparts on the mainland. In 2014, a study by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies concluded that 45 percent of Island households are “cost burdened” – which means they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. And more than 22 percent of all households are “severely cost burdened,” meaning they spent more than 50 percent of their income on housing, constituting one of the worst levels in the country.

That must mean there’s too little housing on the Island, right? Not necessarily. Part of the problem is that single-family homes constitute more than 90 percent of housing stock on the Island. And nearly half of those homes are vacant the better part of the year, owned by seasonal residents. So to be clear, there really isn’t a shortage of housing on the Vineyard; there’s a shortage of affordable housing.

The shortage is most dramatic, of course, in the summer months, when as many as 5,000 seasonal workers descend on the Island looking for work and a bed. Add to that visitors who are quite happy to pay inflated summer rents that can take, say, a $1,500-per-month place in the off-season to more than $3,000 per week – or more. Displaced are those year-round residents, often families, who do the seasonal housing shuffle. It’s not just a cute, anecdotal bunch of twenty-somethings, either: according to data compiled by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, upwards of 20 percent of the Island’s renters move out come summer. And don’t forget the Island’s underground economy, which may mean an additional 3,000 people who are in the workforce and need year-round housing.

And though it’s difficult to quantify, the problem seems to have worsened in the last fifteen years, says Philippe Jordi, executive director of Island Housing Trust, one of the organizations devoted to solving the problem. “It’s here with us,” he says. “It’s not going away. It’s going to impact the [entire] community ultimately. It’s going to impact the businesses, it’s going to impact the civic life, it’s going to impact the people who come here and invest seasonally…”

Those seasonal visitors come here for the beaches and scenery, to be sure, but also the community, the farmers’ markets, the art, the artisans, the food and all that flows from that. “And you just can’t keep that, you can’t maintain that,” says Jordi. “It’s people preservation and not just land conservation.”

The towns and housing groups on the Island have been mobilizing around the affordable housing issue for years, chipping away at it. The Martha’s Vineyard Commission in 2013 released a voluminous assessment of the Island’s housing needs, and just last December released another report detailing a whole range of zoning changes that could encourage more affordable housing, such as allowing more multi-family dwellings, mixed-use buildings (commercial and residential), accessory units, and apartments.

There’s also a proposal, which may reach the state legislature this year, to allow the towns to expand the existing room tax on hotels, motels, and bed and breakfasts to the estimated $87 million seasonal rental market. The resulting revenue could potentially be funneled into each town’s housing trust fund.

The last time the state government seriously considered tackling the affordable housing situation on the Island was in 2006, when a proposal for a housing bank died in the legislature. Loosely based on the land bank model of a surcharge on real estate transfers, supporters hoped it might have made the kind of game-changing impact for affordable housing that the creation of the land bank did for conservation. Fierce opposition from the state’s real estate industry and a general suspicion among voters of additional taxes or fees doomed the proposal, however, and it’s unlikely to be resurrected soon absent a public hue and cry about the need.

At the moment, therefore, incremental change is more likely. While a 2001

report recommended developing 100 to 150 year-round affordable rentals and houses annually, a 2013 assessment targeted 50 new affordable units per year as a more reasonable goal. Waning government funds, zoning barriers, local opposition, and expensive land and construction costs were among the reasons.

By at least one local yardstick the Vineyard is doing well on the housing front: Nantucket, a smaller island with a notably more severe housing problem, has proportionally half as much subsidized housing as the Vineyard does. And despite the myriad challenges, housing advocates on the Vineyard are not about to give up the fight.

“It really comes down to taking responsibility,” says Jordi of the Island Housing Trust. “Like with the land bank [effort], once the community took responsibility for seeing that this place is not going to get overdeveloped, it happened. It happened. And this community clearly has the capacity to do it. It’s just a question of urgency.”

Ron and Roxanne Klein got married on the Island thirty years ago, and never left.

They’re sitting at one of the round tables in the VFW Hall in Oak Bluffs, in the building where they first met over bingo, in the town where they held their wedding reception, reminiscing about their hunt for a marriage license.

The Oak Bluffs town clerk had none; so Ron went to Tisbury. No luck. West Tisbury was also out. “But we were determined to get married,” says Roxanne, smiling. In Chilmark, the town clerk had good news and they filled out the form, and got married on the first Tuesday in August 1985, a fine, clear summer day.

Ron, a truck driver, and Roxanne, who works the early shift inside DeBettencourt Service Station, raised two boys and one girl in Oak Bluffs.

“We know everybody, wherever you walk, wherever you go,” says Ron, with a hybrid accent that has shades of New England and New York City, where he grew up. “If you’re walking down the street, it’s hard to take a walk because people will stop: ‘You need a ride? You need a ride?’”

Do they worry about their kids building a life on the Island? They nod in unison, as they talk about how an already expensive Island has become more expensive for their kids.

“Our daughter is going through that now,” says Roxanne, an Island native. “They’re buying a house, and they’ve been looking, and it’s really tough. They’re finding out the price of things.”

“I know a lot of young people trying to make it here,” Ron says, chiming in. “It’s pretty hard.”

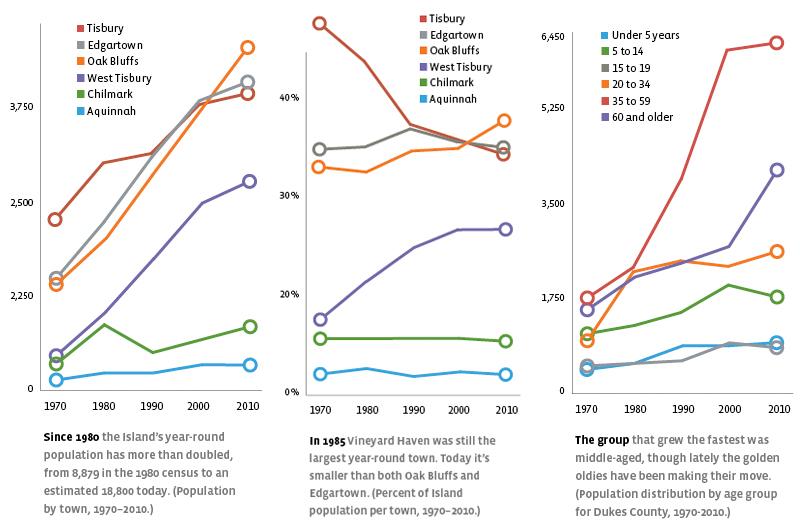

The reality is that many Islanders will never be able to afford a house on the Vineyard. Affordability is a relative thing, however, as the unbroken growth in year-round population over the past four decades shows. The population grew roughly 10 percent just in the past five years and may well top 21,600 people by 2020: statewide, only Nantucket is currently growing faster than Dukes County. Looked at another way, while the supply of houses on the Vineyard has more than doubled since 1980, the percent occupied year round has remained almost unchanged at roughly 43 percent.

The numeric growth in population masks significant structural changes, however, the kind of changes that thirty years from now might add up to a very different year-round Vineyard. Specifically, the population is getting steadily older, with the fastest growing group being what you might call upper middle-aged people – i.e., older than 45. This is not particularly surprising, given the price of housing, since that demographic is more likely on average to have the higher incomes or accumulated assets required.

In a somewhat ironic twist, however, an aging population that is partly a product of the high cost of housing on the Island isn’t expected to alleviate the housing situation. The county housing authority, the towns, and housing groups are looking ahead at the projected demographics with some alarm, because a graying population will need affordable housing not just for themselves but for the health and home workers needed to support them.

But what about those Islanders in the 25-to-44-year-old bracket, which include young families? This is the demographic called “critical to the lifeblood of our communities,” according to one report. The data are sobering. From 1990 to 2010, when the population of those on the Vineyard over 55 years old grew from a quarter of the population to a third of the population, that younger “lifeblood” age group did the reverse, dropping from nearly 37 percent of the population to less than 25 percent. In real numbers, there were 224 fewer Islanders in that bracket in 2010 than there were 20 years earlier.

“This group, largely the children of the baby boomers, simply do not have the economic wherewithal to afford today’s market,” the 2013 housing assessment noted, “and as the figures indicate, many have left the Island.”

Many, perhaps, but not all. Not yet.

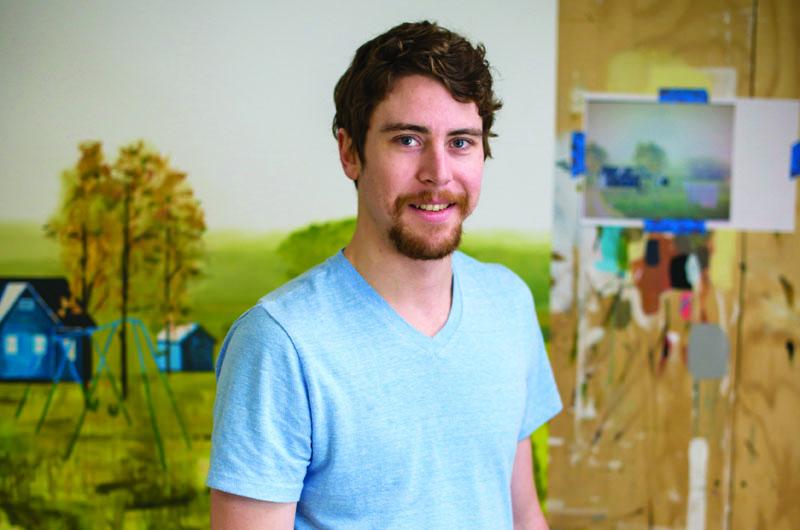

Dan VanLandingham came back. And he’s working furiously to stay. A West Tisbury native, born in 1985, he’s been back and forth, first to college and then graduate school, with a stint on the Island in between, before returning for the long haul a few winters ago.

He has a trained eye about his surroundings, particularly the natural beauty around him. You could say it’s part of his job description as a landscape artist who captures in two dimensions what others have been preserving in reality. Much of his work dwells on the Island’s natural scenes, with occasional features like barns, shanties, and cows.

At The Workshop, a shingled gallery/studio space on Beach Road in Vineyard Haven, he and a handful of other artists paint, display, and sell their art and host events. “My work is about that exact idea – of me being able to capture that kind of landscape in time,” he says. “I could paint the Vineyard for the rest of my life and just be fine.”

Some of his friends do the seasonal housing shuffle, or have called in favors to find housing, or moved off-Island altogether. He’s intent on staying, and eventually buying land in West Tisbury to put down stakes.

“I’m painting my heart out so that I can make enough to be able to do that,” he said. “It’s tough, but I have no doubt I will do it.”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)