It’s hard to miss the Boch mansion on Edgartown harbor. Occupying 15 acres of prime real estate, the 15,000-square-foot home rises up at the shoreline like a beacon. And in many ways it is: with 214 windows and 85 skylights, when the house is lit up, it dwarfs the nearby lighthouse as the brightest spot on the horizon. On an Island filled with luxury houses, it’s among only a handful that people reliably stop in front of to photograph. It’s just that big.

When the late car magnate Ernie Boch Sr. built the home in the 1980s, it was an immediate lightning rod. Neighbors worried that the Vineyard would soon go the way of the Hamptons if houses like it were allowed to proliferate. They rallied to block construction, and declared its three – count ’em, not two but three – kitchens, terracotta warrior statues, grazing llamas, and lawn the size of some municipal airports distasteful. In Island conversations, the Boch name became synonymous with excess. None of it deterred Boch, who made the Vineyard his year-round home until his death in 2003. His wife Barbara lives in the mansion to this day.

But if you want to find their son Ernie Boch Jr. – part-time resident, master of promotion, sometimes rock star, and CEO of the fabulously lucrative Boch Automotive Enterprises – you’ll need to look elsewhere. Specifically, in an unassuming two-story Cape just down the street.

That property, it turns out, is a lot harder to find, even if you know where to look. Accessed by the main drag to South Beach, the house is set close to the road behind a screen of mature trees. There’s no elaborate display or locked gate. There’s no water view. It’s just a house, a guest house, and a one-and-a-half-acre lawn rimmed by manicured hedges and hydrangeas. It’s all very nice. Beautiful, in fact. Still, one can’t help asking: what the heck is Ernie Boch Jr. doing here?

Relaxing, says Boch, leaning back in a seaside-motif upholstered chair. “The vibe in this house is really great, don’t you think?”

On this sunny summer morning, he is dressed in black shorts, a light blue T-shirt, bare feet, and bracelets. His brown hair hangs in unruly chin-length waves that frame a mustache, soul patch, and graying goatee. Though today he is alone, save his long-term PR agent Peggy Rose, Boch is a father of three. It was largely to have a place for the kids and visiting family to stay that he bought the house, he says. Improbably, the family mansion (which he refers to as “the big house”) has only four bedrooms.

“I was looking around and it was such a good deal I had to buy it,” he says of finding the nearly 5,000-square-foot house in 2009. “It was the perfect timing. [The builder] couldn’t sell it. Economic downturn. The moon and the stars aligned.” Boch paid $2.95 million for the property and began the process of turning it into his own Island retreat. He dug out around the foundation and added windows to the basement, as well as a gym, a king-sized bed, and bunk beds, bringing the total number of bedrooms to seven. He also ripped up the yard and “tuned up” the bathrooms. Overall, though, he kept the builder’s vision intact.

The result is a home that is airy and inviting, all open floor plans and neutral colors with coastal-themed artwork and domestic details. In the great room, kids’ board games line the shelves. Boch credits the decor to Anthony Catalfano, a “big deal designer in Boston” who also styled his private jet and his other houses in Norwood, Massachusetts, the West Indies, and Florida. (Not to mention his father’s Edgartown palace.) Each home has its own style appropriate to the setting, says Boch. His primary residence in Norwood is very formal and fancy. “This is more vacation, very casual.”

And yet it’s not without its high-end toys. “This is the heart of the house, all the video, all the audio, all the cameras, all the cable,” he says pointing to a rack of black servers locked away in a basement closet. “I can burn a CD at my house and it pops up here and at my house in the West Indies.” It also keeps track of approximately twelve security cameras that he has trained on the property – so that he can monitor things while he’s away, he hurries to explain. “It’s not because I’m paranoid by any stretch of the imagination.”

If the thought of Boch hiding out here, just a few minutes down the road from his family’s infamous “big house,” at first seems peculiar, it soon starts to make sense. Smart and savvy, he has a palpable drive to keep his automotive empire on top. But he’s also a man of irrepressible teenage-like enthusiasm, bouncing around in conversation from one topic of interest to the next. Over the course of the next few hours, he will enumerate his long Vineyard history, which began with a family visit in 1966. He will tell of hours spent chasing after the ferries on a Boston whaler and collecting quarters by the dock, of his first kiss at an inlet in Vineyard Haven, and his first sexual experience on South Beach. He will strum an acoustic guitar (“I always keep a guitar around,” he says), detail his foray into music, and rattle off the names of albums he loves (Rod Stewart from ’68 to ’74; Elton John’s first four records only). He’ll talk about his time spent on the Vineyard (typically three weeks in the summer, if he can swing it, and several trips during the fall and winter), and what he likes to do while he’s here. No private beach for him, he says, he and the kids enjoy going to Katama. “It’s right down the street. It’s nice. And the waves, you can’t beat the waves.”

Boch is a man who can afford to do whatever he wants, and can buy just about whatever he wants – and he does. But he likes what he likes, seemingly regardless of cost, taste, or social expectations. And what he likes on the Vineyard apparently is to unwind in entirely normal, low-key fashion. Outside, in the backyard, he points to speakers tucked discretely into the hedges. The previous night, one of those crystal-clear late summer evenings when even the Milky Way is in full view, he spent time observing the stars and listening to tunes – though not for too long or too loudly, he says. “You have to be a good neighbor.”

The Edgartown version of Ernie Boch may be understated, but in Norwood his showmanship is on full display. Here is the home of the fabled “Automile” – a term his father popularized to promote his cluster of dealerships along Route 1. Today, Boch’s seven Massachusetts dealerships, rent-a-car and collision service centers, and Subaru import business bring in more than a billion dollars. And here, in the midst of a largely middle-class community of some 30,000 people, is Boch’s year-round home: a 16,000-square-foot, 21-room sprawling compound that has overtaken an entire block.

Boch purchased the home in 1997 and reportedly spent more than a decade and some $30 million transforming it from an historic 1920s mansion into what might properly be described as an homage to his whims. Though work on the house is complete, improvements to the property continue. “I’m building a little hardscape area with a fire pit. I’m building an amphitheater. And over in the corner I’m building a mausoleum where I’m going to be buried. It’s going to be amazing,” he says. Additional plans include a scene from feudal Japan, complete with a traditional Japanese home and dry riverbeds. He intends to donate the land to the public when he dies.

In 2013 the Wall Street Journal reported on Boch’s feuds with neighbors in Norwood, who complained of constant construction noise and lavish annual 600-person parties, the likes of which have included belly dancing, hookah dens, and performances by the Go-Go’s. In a move he might have learned from his father, who was known to purchase almost all available properties around his Norwood dealerships, Boch simply bought up any surrounding houses he could get his hands on. “I bought the whole entire block,” he says. “I just finished buying it. And I’m knocking the last house down this week.”

The family wasn’t always able to respond in this way. “I didn’t grow up poor or anything,” Boch says. “But by no means was [my father] close to what I’m doing now.” In fact, the Boch brand had a humble start as a gas station and repair shop, just minutes away from the current scion’s home. Boch’s grandfather, Andrew, opened the gas station in the 1940s and turned it into a Nash dealership. His father and his uncle joined the business in the mid-’50s. “He gravitated toward the front of the business and his brother gravitated toward the back of the business and you know, they struggled.”

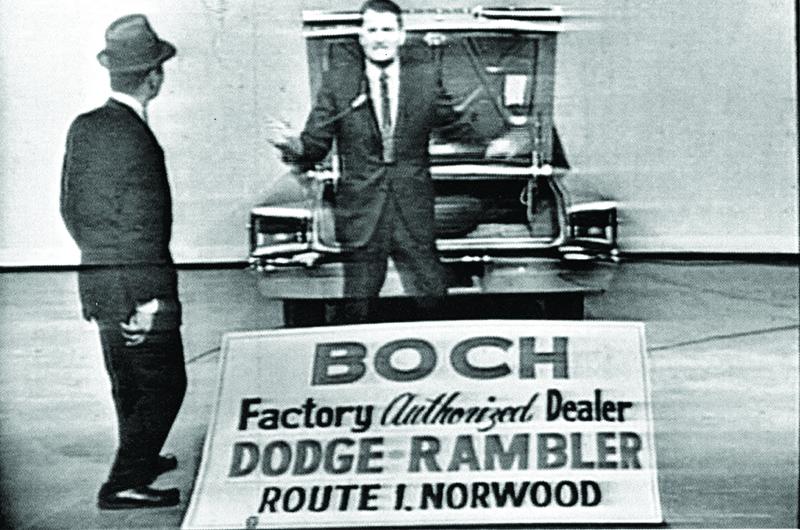

That began to change in 1964, when Boch Sr. took to the airwaves with his first commercial. A savvy marketer, he smashed windshields with sledgehammers to simulate slashing prices, pretended to blow up the competition, and exhorted would-be buyers to “come on down!” The gimmicks worked. By the mid ’70s he had expanded to sell Oldsmobile and Toyota. Perhaps most important, he took over the Subaru distributorship for all of New England just as the market for Japanese cars was starting to explode.

With business booming, many assumed the younger Boch would follow in his father’s footsteps. But Boch had other ideas. His father was a tireless worker who didn’t smoke, drink, or eat red meat and spent almost all his waking hours attending to business, even while in Edgartown. “I come out here to work,” he told the Cape Cod Times in a 1996 interview. “I think I’ve been in the hot tub once. I’ve never laid on the hammock.” The younger Boch, on the other hand, loved to play guitar and applied to Berklee College of Music in Boston. “I was shocked that I got in,” he says. “You know, I learned real quick, I mean I play okay, but I’m not a great player.”

A pragmatist at heart, he decided he could try to make a million dollars playing music or make a million dollars in the family business and then play music. He chose the latter and began working his way up the company’s ranks. When his father died of complications from liver cancer in 2003, Boch took over as the face of Boch Automotive, which has grown to be the largest private importer of Subarus on the planet. “Last year and this year, the six states of New England will beat the country of Canada, the continent of Australia, the country of Russia,” he boasts. “Those goddamn Chinese beat me by 200 cars last year, and I want to beat them this year. But China is two distributors and I beat them individually.” (Mission accomplished: in a recent conversation, he says he beat China in 2014 by 6,600 units.)

Along the way he’s infused his own interests into the family business – or more precisely, he’s found a way to make the family business a reflection of himself. Gone are the tailored corporate suits he wore in his first commercials. He grew out his hair, formed the band Ernie and the Automatics, hired backing musicians from the rock group Boston, and took his act on the road. His dealerships began selling Aerosmith drummer Joey Kramer’s “Rockin’ & Roastin’” coffee. In the span of a few years, Boch Automotive had gone from featuring the father’s sidekick “Kramer the magical donkey” to the son’s guitar riffs. Boch had turned up the volume to eleven.

These days he’s handed over management of the dealerships in order to focus on marketing. Along with a business partner, he creates almost all the original music for Subaru New England ads. He also devotes significant time to his nonprofit organization, Music Drives Us, which supports music education in New England public schools. We run the company with a different philosophy,” he says of his father. “He ran the company with a certain philosophy and was extremely successful. I run it with a philosophy and you know, some people say I’m successful. There’s more than one way to skin a cat.”

Boch’s philosophy toward the Vineyard also appears to have mellowed from that of his father, who, he says “always, always, always liked this place.” The elder Boch had what might be called a rocky affair with the Island, filled with decades of hard-fought battles with neighbors and town officials. “He had a boat and we used to spend the summers in Falmouth...and we would take day trips to the Vineyard,” Boch recalls of the family’s first visits in the mid-’60s. “And then we started staying for a week. And then we started doing all summer.” But when it came to building his own home, he received a chilly reception. “There’s a lot of bigger houses on the Island [today],” Boch says of the controversy. “He was really just the first guy to do it and put three kitchens in, and you know, do it up nice. And it was the early ’80s and the town was a little…I dunno, conservative, not as understanding as it is now.”

The coming years brought more uphill battles that Boch Sr. met head-on. He was cited in local newspapers for filling in a wetland in front of his home, altering a pier, and installing a 1,000-gallon underground fuel tank and a partially submerged tank without special permits. For years he tussled with local authorities in a bid to turn the so-called Boch Park, a Vineyard Haven waterfront lot, into a parking area. Though he and his wife attended many of the local government meetings in person, occasionally staying until the early hours of the morning to defend their plan, the lot remains vacant.

For Boch, Sr. it was about more than parking. He and his wife Barbara told the Boston Globe that the island they had moved to for what they expected to be a booming social scene had been neither “welcoming” or “inviting.” “They haven’t even met their famous neighbor, Walter Cronkite, let alone been invited over for drinks,” the article reported. “They are not on the social lists of the old-money sahibs who share with them the splendid life on the harbors of Edgartown, Vineyard Haven, and Menemsha.”

Perhaps it’s the familiar story of new money getting older with each generation, or simply just a case of a man who spends his life in the spotlight seeking a quiet refuge, but if Boch feels a similar lack of connection to the Island social scene, it’s likely by design. He doesn’t know many people here anymore, he says. All his old friends have moved away. Still, he chooses to keep relatively quiet. His most recent headlines in the Island newspapers have been for charitable causes. In recent years he donated $65,000 for a new drug-sniffing canine unit for Island police, $70,000 to outfit a search-and-rescue boat for Edgartown harbor, and $100,000 to renovate the Vineyard Playhouse. In February he presented a $34,000 check to the Tisbury School to send eighth graders on a trip to Washington, D.C.

As for recent speculation about upcoming changes to Boch Park, he waves it away. “That’s just part of getting my shit together,” he says of his 2013 request for boat builder Ted Box to vacate the property he had rented for several years.

Besides, he explains, that Box was building a boat on the site at all was the result of a hilarious miscommunication. It started when friend and musician Livingston Taylor called Boch and said, “Hey, Ernie, I got a friend who wants to build a boat and I’m wondering, can he put it on your property for a couple months?’” Boch said no problem.

“So I get a call, ‘Hey, Ernie, I want to build a boat.’ I go, ‘How long are you gonna be there?’ ‘About three months.’ Ted Box goes in. Then Livingston calls and says, ‘You didn’t let my friend build the boat!’ It wasn’t Livingston’s friend. It was Ted calling me out of the thin air!…And he was there three years!”

Boch laughs off the story now, but that doesn’t mean he wouldn’t eventually like to see the property developed, possibly into condos with a commercial component. It’s just that the current zoning won’t allow it and he’s not looking for a fight. “I would support changing

the laws, but going in there and acting like an asshole, no I’m not gonna do that,” he says. “I’ll leave the lot like that if I have to.” Nor does he have plans to offload the property. “Why would I sell it? I like it,” he says. “I like the area. I think that the town will wake up and do something nice.”

He’s in no rush, in other words. And as for worrying about being left out of some Island social scene – real or imagined – Boch actually prefers to visit in the fall and the winter, when he makes regular trips. “My perfect day would be to come here with my girlfriend, family, and hang out. Have a nice breakfast, hang out with the kids, maybe go by South Beach, take a look at big waves, something like that, and then have lunch at the Newes.”

“It’s the quietness that I love. Absolutely adore it,” he says. “When I leave my little fiefdom, I don’t really want to see anybody, or do anything. I want complete isolation. I get people saying, ‘Why don’t you get a place in the Hamptons? Why don’t you….’ Why would I possibly do that? I just couldn’t even imagine it. Couldn’t even imagine that.”

14 comments

14 comments

Comments (14)