Once, long ago, I fell in love with a house and then I fell in love with the man who built it. I was twenty-six and considered myself worldly, although I hailed from the Midwest. But Sam, the man whom I met in Boston one night and who the next morning whisked me with my six-year-old son to the Vineyard, showed me something I didn’t know could exist. A handmade house. On an island.

From the ferry deck that first chilly October morning, we could glimpse the roof of the house that Sam had built on family land during his summers in architecture school. We walked to Owen Little Way, a short road ending in a town beach. Entering the property meant skirting a rundown, white-clapboard cabin into a courtyard formed by the two shingled buildings Sam had designed. One was thin and long with a steep pitched roof, an austere two-bedroom structure of New England pedigree that looked sliced in half, like a baguette cut lengthwise.

In the second building, the main house, timbers framed a soaring space that gathered light through huge, clerestory windows. Inside, Sam laid logs in the fireplace and soon, with the sun pouring in and a fire roaring, we were warm. I looked around the place in awe, the driftwood couches, a lamp fashioned from barrel staves dragged from the beach, a hanging central light with industrial bulbs protruding from a cube of raw wood. I’d spent a lifetime surrounded by intellectually accomplished men but had never seen one use a hammer. Sam could do it all: plumbing, electrical wiring, a monumental chimney. He could dream it up and put it together.

Not only did this little compound have character, it came with an eccentric history. Sam’s great-grandfather, Frank Ferris, had been a man of wealth whose family, The New York Times reported in June 1889, was “already enjoying life at Restcliffe cottage, which is built on a high bluff on the Highland Drive, commanding a magnificent ocean view with its daily panorama of passing vessels.” The following year Frank Ferris would expand his “cottage” on thirteen parcels of East Chop land into a “castle,” a magnificent turreted summer house surrounded by verandahs, which became the talk of the burgeoning resort because of its splendid indoor plumbing. Fifty years later, new owners named it “The Colossal Fossil.”

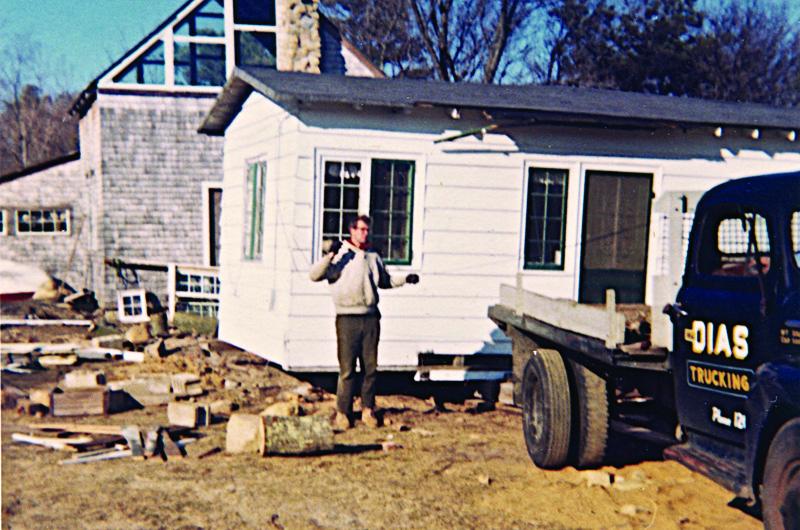

Frank’s daughter, Ethel – Sam’s grandmother – married James Knapp, a Yale-educated successful New York businessman. They lived regally in Connecticut until the Great Depression when, financially ruined, James turned to selling encyclopedias. As a widow, Ethel spent her summers on this small sliver of Owen Little Way, living in a Sears, Roebuck and Co. mail-order house – the now downtrodden cabin facing the street. In an act of creative repurposing, Sam’s father, also an architect, had made space for his own family of six by moving a former ticket office from the Island ferry wharf onto Ethel’s land. A few years later he added an abandoned American Legion shack, formerly used to house chickens.

Such were the family summer accommodations in 1964 when Sam assembled a team of family, architecture students, and friends for a three-summer effort that resulted in soaring ceilings and sleeping lofts and a grand chimney of glacier-rounded Vineyard stone.

On my first visit we walked the empty beaches, sampling apples along the way. At dusk we waded from the Owen Little Way beach to rocks where we gathered a bucket of mussels, blue-black shells dotted with barnacles and dripping seaweed. We hosed off sand, twisted apart clumps, scrubbed them a bit, then steamed them as we have ever since, in a splash of white wine. I had never seen a mussel, never heard of moules marinière, nor had my son who was, after all, only six. Sam served up a heaping bowlful, with musky sea scent rising in the steam. We watched Sam pull ivory flesh from the shell and, holding its beard, swish the mollusk in cooking broth. He dropped it in his mouth. My fearless son followed. I could do no less.

We spent most weekends that fall sleeping in front of the fireplace as the temperature slid down. Sam introduced me to such Vineyard customs as gathering beach plums. I enjoyed picking the small, bitter fruit, since new love had me primed for any peculiar ritual, but had no inclination to plunge into his sister Lucy’s tradition of making jelly. Carted back to Boston, my pail of beach plums lurked for days while I toyed with the consequences of tossing out the contents before finding a recipe for a liqueur called beach plum cordial: sugar, a quart of vodka, and beach plums in a big jar, the mixture inverted daily for a month.

Eight months after we met, friends and family gathered on the Vineyard for our June wedding. My Aunt Pat, an art historian, described the first night of celebrations, a bridal supper at the Owen Little Way house hosted by Sam’s parents: “We must have been at least thirty at a long table, and we looked sort of like Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding – cats, dogs, children; beef stroganoff, asparagus, the salad, some toasts…”

At low tide the next morning, Sam, his best man and I braved the chilly Menemsha waters to pry mussels off the breakwater rocks. Before dusk, close to a hundred family and friends would gather for an Owen Little Way beach party to feed from a huge mussel pot and slurp down clam chowder. Later that evening, before we boogied to a band called The Psychopaths, Sam’s twin sister Harriet blew in from Yugoslavia. As Aunt Pat wrote, she and her younger sister Polly caused a sensation “both with heavy blond manes and looking rather like Lady Godivas with clothes on.”

We held our wedding in a meadow at the foot of Owen Little Way with the Vineyard sound beyond and sea gulls above. The Rosa rugosa bloomed spectacularly. My grandmother, bewildered by the 1960s, called my purple silk mini wedding dress “sort of a bathing suit,” and beamed with pleasure that Sam married in a real suit.

During the following decades the family expanded and reconfigured, some moving to Europe for a stint while we spent several years in Africa. Children grew. In summer, the Owen Little Way house embraced the occupants – sometimes a little shakily. We descended with three rambunctious children. One niece installed a cage with her pet python. Two nephews became rock musicians and used sound absorbing mattresses to line the cabin walls.

By and by we tore the cabin down, replacing it with a more dignified two-story cottage. Once or twice someone stayed into winter, trying to rely on the fireplace. Families grappled with sharing access and responsibility, a tale repeated in countless summer houses, each idiosyncratically. Finally we divided up the various properties Sam and his three sisters had inherited, and Sam and I took over Owen Little Way.

This year the house turned fifty – a big birthday, I tell the grandchildren. I want them to know how their Grandpops found an eighteenth-century barn to demolish in Edgartown for the bones of our house; how he salvaged siding from the World War II airport army barracks for the skin; how he bartered for the windows and plate glass that bring so much light into our lives. They should understand that their great aunts worked hard de-nailing old boards and shingling and painting trim – endless, critical tasks. Grandchildren should remember that their aunts and uncles grew up here, and helped in countless ways to keep the house alive.

Just as so many decades ago the house was Sam’s escape from architectural theory into practical practice, so the pleasure returns every year as our wintertime ideas become early summer projects. Sam collects weathered old doors and turned several into handsome new couches. I found a bag of paper lanterns at a yard sale and strung an homage to Illumination Night across our living room. We bought old columns and railings that Sam fashioned into whimsical porches and rain shelters, softening the facades. I painted large floorcloths and made Vineyard-inspired collages. We planted a magnolia tree that for one glorious month offers us huge, cream-colored blossoms, one at a time.

4 comments

4 comments

Comments (4)