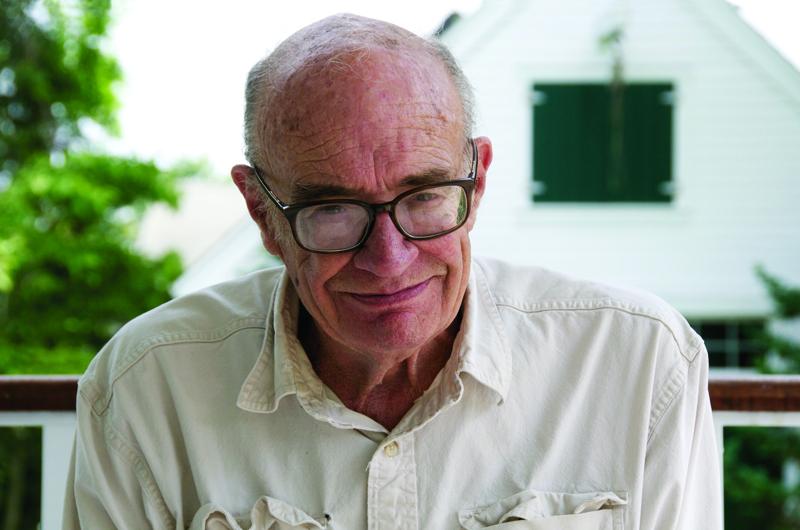

Ward Just is seventy-eight years old. He still smokes Camels, not a chain smoker now, but the smoke and ash are often present, in the air and in the timbre of his voice. He lights his cigarettes at the gas stove when at home, leaning his face over to get close enough to the flame and then inhaling deeply. Matches would do, of course, but where is the adventure in that.

Just, whose eighteenth novel, American Romantic, came out this past spring, has said that the life of a writer is actually a dull affair, and mostly involves sitting in a chair fiddling with one sentence after another for eight to ten hour stretches. He has seen his share of excitement, as a reporter and a war correspondent, and yet for him the real thrill has always come from the words, holding each one of them up to the light, and then setting them carefully down on paper. He wouldn’t have it any other way.

There was a teacher back in his small hometown of Waukeegan, Illinois, who let the kids in the class do whatever they wanted for thirty minutes or so each day. Young Ward, at age eight, always chose to tell stories, ghost stories usually. He loved the suspense he could create in the room, spinning tales off the cuff. Those kids, not to mention the teacher, were very lucky indeed, getting a first glimpse at what a true storyteller looked and sounded like. Although in terms of time and place those days are long gone, to stop by Just’s house in Vineyard Haven today and sit with him at his table is to see very clearly that the boy has never grown old. He hasn’t even had to change his preferred subject matter, not really. It’s just that the ghosts he talks and writes about today are often from Washington, D.C. Talk about scary.

American Romantic begins at the start of the Vietnam War, with a young foreign service officer just starting his career when “the war was not quite a war, more a prelude to a war.”

It’s terrain Just knows well, having been a war correspondent for the Washington Post at the start of the Vietnam War.

The main character, Harry Sanders, soon finds himself behind enemy lines and is injured. Just also knows this terrain all too well. In June of 1966 Just went out on patrol with a reconnaissance unit in Dak To, a village in the highlands about fifteen miles from the Cambodian border. “The idea was to try and find where the enemy was,” he said in between sips of espresso at his home. When he started to talk he leaned back in his chair and spread his arms out wide as if to carry the memory literally in his hands. Then he leaned forward, elbows on the table, and continued. “And so we just kept going along these paths. Plainly the enemy had been there but we didn’t know where the hell they were. And I never quite understood, once we found them, what the hell we were supposed to do. There were only forty of us.”

They did find the enemy. Or rather, the enemy found them and they were heavily outnumbered and pinned down. The commander of the unit, Lewis Higinbotham, called in for artillery help, which began setting down a wall of exploding shells that surrounded the unit.

“Like a donut and we were the hole,” Just recalled. “It was really a curtain of fire, so the Viet Cong couldn’t move forward, couldn’t get through the wall of fire. My memory tells me they fired 1,100 rounds of 155 millimeter – this is going to be roughly right – and two hundred rounds of a sort of smaller gun. Think about that. Fourteen hundred of these shells are going down and this whole thing went on for about three hours. So they got close enough to throw hand grenades anyway. At the end of it there were eight dead and something like sixteen wounded of forty people. Some heavy casualties.

“To watch that stuff up close is mind altering to tell you the truth, and a little bit life altering. I’m loath to say exactly what alteration resulted, except that you have an idea of however bad things get in the future they are not going to be as bad as this. You can have a bad hair day, but it ain’t that.”

Just was one of the injured, the result of an enemy hand grenade, but a few months later he was back in the field covering the war again. In all he stayed in Vietnam for about eighteen months, returning to the States in time to cover the 1968 presidential election when Richard Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey. It would be his swan song as a reporter. He has said that “After Nixon my thirst for fact had vanished.” But the truth is he always had his eye on writing fiction. He had tried to write a novel a few years before, taking a leave of absence for six months and holing up in Spain with his wife and two daughters. But it didn’t work out. By his own estimation he just didn’t know enough about the world then, how it worked and how people truly behaved. He was also still trapped by the influence of Hemingway. Think about it. A young journalist from Illinois becomes a war correspondent and then goes to Spain to write

a novel.

“I should have recognized what a stupid thing that was. Dangerous.”

Not long after the election, Just took another leave of absence. He had first arrived in Washington in April of 1961, “when the Kennedy romance was in full bloom.” He had worked for Newsweek and the Washington Post during the Bay of Pigs, the assassinations of John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. He had covered politics and wars, seen battle and had almost been killed. The Vietnam War had also given rise to a new kind of journalism, one in which fictional techniques such as setting and place and dialogue allowed for an audacity of prose to rival the events on the front line. David Halberstam, Michael Herr, Stanley Karnow, and Seymour Hersh, to name just a few, all came of age in Vietnam.

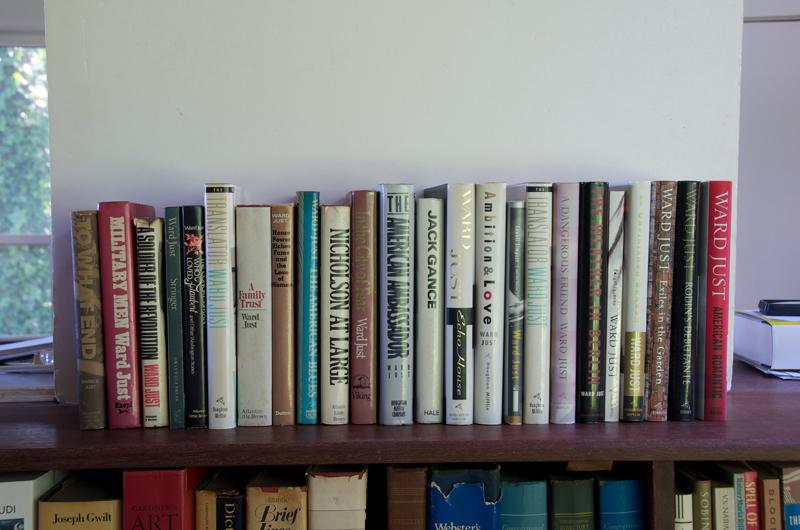

“I did feel that for me to stay on in the business after 1970 I wasn’t going to learn much more, and if I was going to do what I had wanted to do my whole life, which was to write fiction, I bloody better well start then. I took leave in ’68 to write a novel which was published in ’69. Wrote the damn thing in three months.”

The result, A Soldier of the Revolution, set his career in motion and he immediately began work on his next book, and then his next, and his next, publishing a new novel every two or three years for the last four decades.

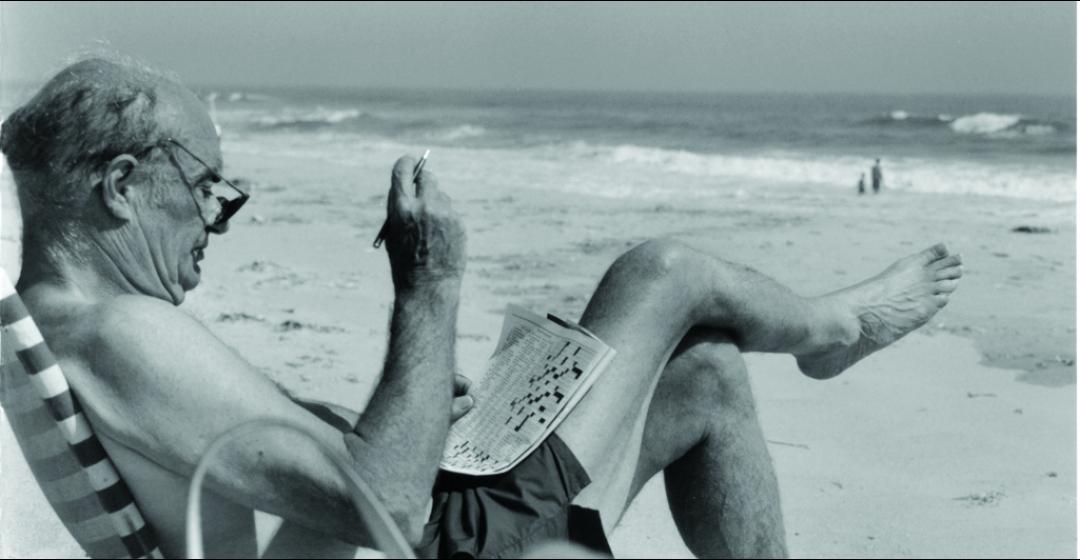

Writing a novel is a lot like playing a game of patience or solitaire, Just has said. “You sit around for a few hours and then write a sentence. Then in a few more hours you write a second sentence. Then you rewrite the first sentence to fortify the second sentence. This goes on all day long until late afternoon. Then at the end of the day you erase all the adverbs. Finally you have a clean piece of paper with the fortification of a battleship. And two and half years later you have a novel. And then you start all over again. That’s the writer’s life.”

And this has been his life, at least for a third of each day, since the late 1960s. He calls himself a “lucky chap” because he has been able to do exactly what he set out to do with regard to his writing life. It could be argued, however, that the only reason he has been able to create his writing life the way he wanted to is because he worked so hard at it and refused to give up.

From the beginning, critics and fellow writers were enthralled with his craft, but it took the general public, often a slow-witted beast, longer to catch on. Not until his eleventh novel, Echo House, was nominated for the National Book Award in 1997 did he begin to gather a wider following. His fourteenth novel, An Unfinished Season, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2005, and some critics say that American Romantic is his best book yet.

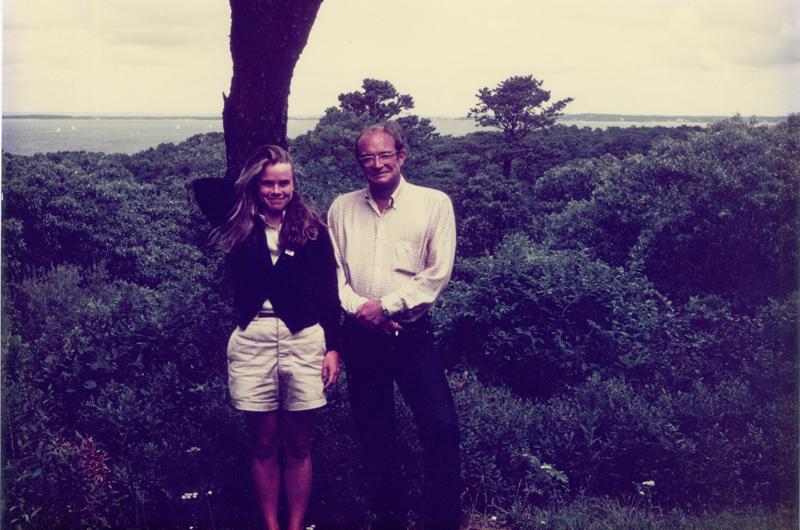

It might seem fitting that a man who knew exactly what he wanted to do with his life at eight years old and then plotted his course with precision would also decide very early on where he wanted to live. Just first visited the Vineyard in his early twenties, invited by a friend. He didn’t see the Island again for another two decades, and yet the place stuck with him. One weekend was enough for the Vineyard to burrow deep under his skin and enter his bloodstream.

“Specifically Lambert’s Cove stuck in my mind all that time. I just loved the look and the shape, the sickle shape of Lambert’s Cove Beach.”

He returned to the Island in his forties.

I said the hell with it, I’m going to go back to the Vineyard and I came down and rented a place in Lambert’s Cove. Found out who you had to call. Filled the place with friends and they arrived and came and went, just had a great time and that solidified my thought that if I could ever find a way to do it, to come down here and live, I would.”

He and his wife, Sarah Catchpole, bought a house in Lambert’s Cove in 1982 and moved here full time in 1992. A couple of years ago they moved to Vineyard Haven.

Not surprisingly, Just is already at work on his next book. He still spends most of each day writing, but admits his powers of concentration are not what they used to be and he can’t put in quite as long a day at the writing desk, perhaps down to just six hours a day from nine or ten. But with age he feels he has learned to be more economical and quicker to realize when a passage is “bogus.”

And no matter what happens, he always has the 1960s to help stoke the creative juices. Not that every book of his uses that era as its source material. Rather, it is more like a source of heat, the atmosphere of a time when the future of this country was in flux and attitudes shifted forever.

“It’s funny, when you’re part of a period that becomes really iconic in American life, whether you think it’s all bullshit or whether you buy it to the extreme, it really was a time when people believed and then very shortly after they ceased to believe. To have been not at the center of events but kind of on the fringes during that period was really a life changer, I’ll tell you.”

And his latest book?

“This one begins in the middle 1960s but it doesn’t have anything to do, at least not so far, with the Kennedy administration. It has to do with a bunch of people in an old house, and having difficulties getting through the day. It’s bad luck to talk about a book when writing it. I’ve already said too much.”

And with that Just is ready to get back to work again. He stands and walks his visitor to the door. Then he heads out to his writing room, still at heart an eight-year-old kid with a story to tell.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)