There’s just something about birds. From the early, primitive ravens in Cindy Kane’s first exhibited work, to the migratory and map-like patterns of smaller birds that sweep across her later pieces, flight, form, and feathers are clearly a source of creative inspiration for the artist. But don’t ask her how, or why.

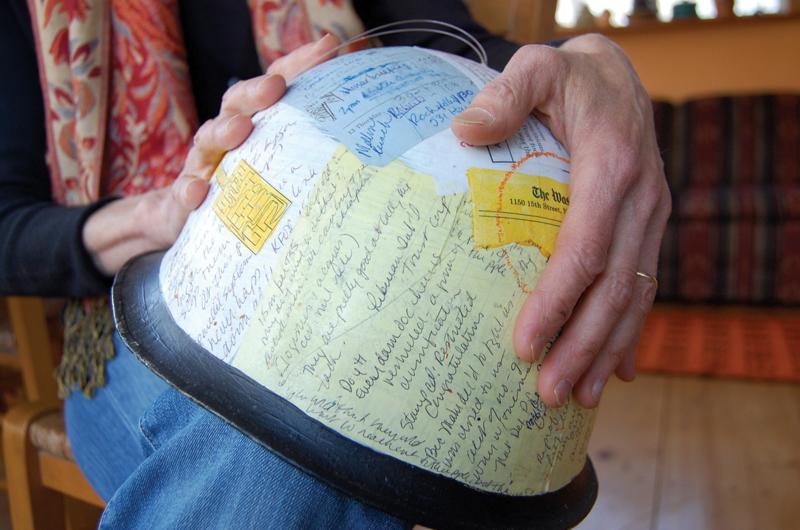

Tall and slender, with a voice that is at once gentle and self-assured, Kane talks about her process in a way that gives the impression she is fully comfortable letting the work speak for itself. And speak it does, in tones ranging from the soft and subtle, as in her new, ethereal paintings of dresses, to the politically assertive, as in the collaborative mixed-media installation involving Vietnam-era soldiers’ helmets and notes from fifty war correspondents. The latter work, called The Helmet Project, hung in the round at the Cheryl Pelavin gallery in New York and at the Carol Craven Gallery on Martha’s Vineyard.

Born in Alexandria, Virginia, Kane discovered a passion for creative pursuits at an early age. “Art was always my identity, from childhood,” she told me recently when I visited her in her studio, which is at the end of a long, dirt road in Vineyard Haven. “I’m the oldest of four girls, and my role in the family was the artist. My father was a writer and my mother was also artistic. It was a very progressive neighborhood.”

After high school, she forwent college in favor of an open-ended bus ticket cross-country. “In those days, you could take a Greyhound bus – it was called an Ameripass – and you could take a bus across the country for ninety-nine dollars. I wanted to go as far away from Virginia as I could. I went to California, Arizona, and then I found a job at the Grand Canyon.”

When she wasn’t at work with a trail crew in the backcountry of the canyon, she drew. “I had a rapidograph pen. I made very intricate drawings of insects,” she recalled. In the years since her time in the wild – years that took her to Paris and Berkeley and New York, and finally to the Vineyard in 1996 – the natural world in its varied forms has featured prominently in her art. Yet, as with her birds, Kane is reluctant to pinpoint this, or any one lived experience, as inspiration for the impressive body of work she would go on to create.

“I think you’re talking about muses and I really don’t know how they operate,” she said when asked about artistic influences; how she moves so fluidly and deliberately from one concept or series to the next. “It’s a mysterious thing. I trust the muses that are around me, and I really believe that we have muses that interact with us. Sometimes you’re receptive and sometimes you’re not. And sometimes they want to talk about something complex and sometimes they want to talk about something simple.”

Before moving to the Vineyard, Kane and her husband, woodworker Doron Katzman, lived on a houseboat anchored at Manhattan’s 79th Street Boat Basin. “You know how some guys collect cars in their driveway?” she laughed. “Doron had boats on moorings. I used one of the boats for a studio. When our daughter Tova was born, I used to row out to the studio with her in a little car seat.”

Eventually, Kane and Katzman decided to search for a place where they could lead a quieter life. “I think New York crushed me,” she admitted. “It was a very difficult place for me to live. It didn’t really serve me well as an artist. I’m not temperamentally suited to be a creative person in New York.”

The writer and collector Ellen Pall remembers Kane’s houseboat days firsthand, and says of her friend’s transition to the Island: “[In New York] she was mostly doing small things, and then they moved to the Vineyard, and an amazing and almost hilarious thing happened: her work went from being six inches wide to six feet! It was very startling and amazingly great.” Pall compares the transformation to a novelty toy that expands when submerged in water. “She just flourished.”

For Kane the transformation was, in part, about finding a new routine. “I’m very orderly,” she said, glancing around the cozy, garret-like studio built for her by her husband and nestled above his own carpentry workshop. The room is warm but sparse, with just a few stacks of art books and show materials on a shelf in one corner, and a rotating selection of works-in-progress spaced neatly on the walls. “I need a lot of order. I need a vibe that’s consistent. My radio station, my music, my table here. I’m a creature of habit. I do Tai Chi every morning. I have my green tea. That seems to serve my work.”

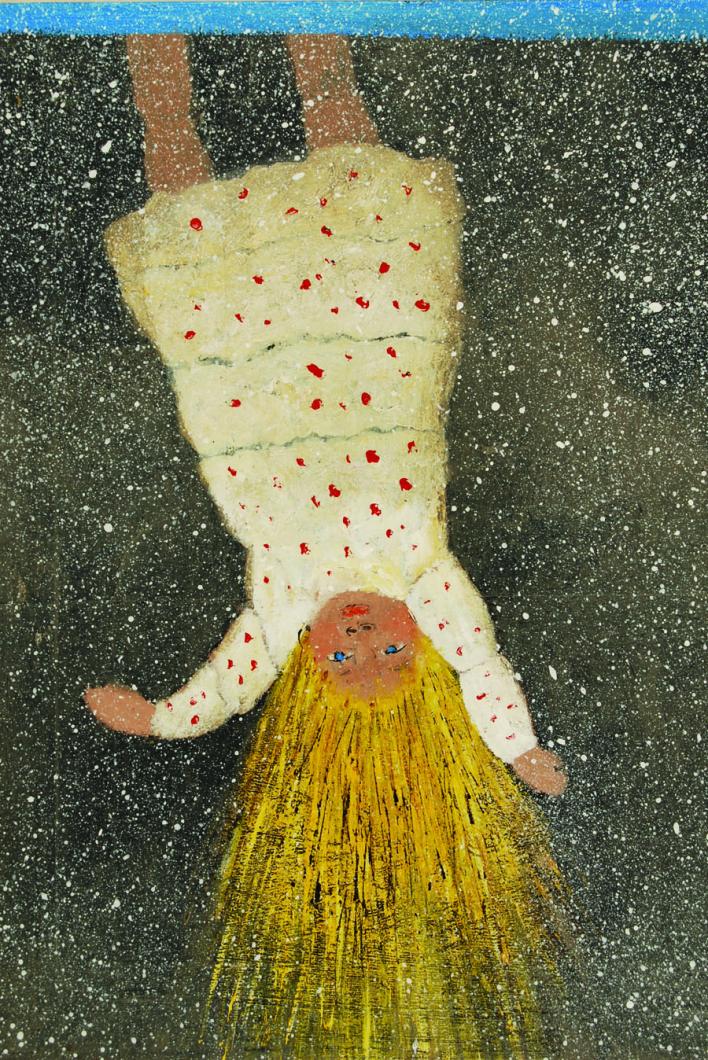

Perhaps it is because inspiration calls to her from so many places that Kane hesitates to identify her work with any single creative wellspring. There are, however, a few themes she finds herself returning to again and again, themes that are represented on her website, cindykane.com, as distinct categories: Maps; Birds; Toys; Feathers, Stones, and Wings. Scenes and mementos from her personal life find ways of seeping into her work as well. When her oldest daughter, Tova, left for college, Kane made a collage of some of Tova’s childhood drawings, which she later used as a textural base for one in a series of dress paintings. (Kane’s younger daughter, Nelly, was born on the Island and is a student at the high school.)

It is to this process of repurposing old projects that Kane credits her prolific artistic output. “I rework paintings a lot,” she told me, eyeing the handful of her most recent pieces hanging on the studio walls. “Nothing is really safe in my studio if it’s lived around for too long.”

A painting that comes back from a show unsold may hang around temporarily before Kane decides there’s something about the texture, or the content, that is calling out for reinterpretation. For example, the piece that began as a collage of her daughter’s sketches was then painted over many times. She pointed to a large, ornate stencil, which she had layered over the collage. “I got this texture thingie in Chinatown; this was the first time I put it down. And then it just felt so lacey, so dress-like. That was the first in the dress series.”

“I like the idea of working on a skin,” Kane said of the various recycled materials she uses. “It’s just got a whole narrative underneath. It’s got a story there that’s just so compelling. It’s like a secret I share with the painting. It’s like a vibe, like stepping on old stones.”

Skin and texture are essential to Kane. For a time, she painted on squares of roofing tar paper her husband had lying around from the renovation of one of their boats. Mostly, though, she works with acrylic paint on luan panels, a type of tropically sourced plywood. “I prefer wood to canvas because with canvas there’s a buoyancy, and the bouncy quality bothers me. I like the tap-tap-tap.”

In her ongoing quest for textural depth Kane has also been drawn to the written word, most notably in the form of calligraphic lines that appear in the background of many of her paintings. “As devoted as a reader as she is, I don’t really think it is about the words,” Kane’s friend Pall suggests. “I think it’s a mystical way of suggesting communication. A physicalizing of some impulse behind writing. A picture of the impulse to communicate.”

In her series Mapping Writers, Kane reached out to a number of established Island authors, including Jules Feiffer, Rose Styron, and Geraldine Brooks, and gathered hundreds of pages of handwritten notes. These she arranged as the backdrop for a series of paintings, many featuring her beloved maps and birds. “The mapping writers pieces I thought created a wonderful synthesis of creative disciplines,” Brooks wrote in an email. “I love the way the words seem to bleed through the paint and the images – although in no way overtly related to the words – somehow engage in a conversation, or a call and response, with the writing.”

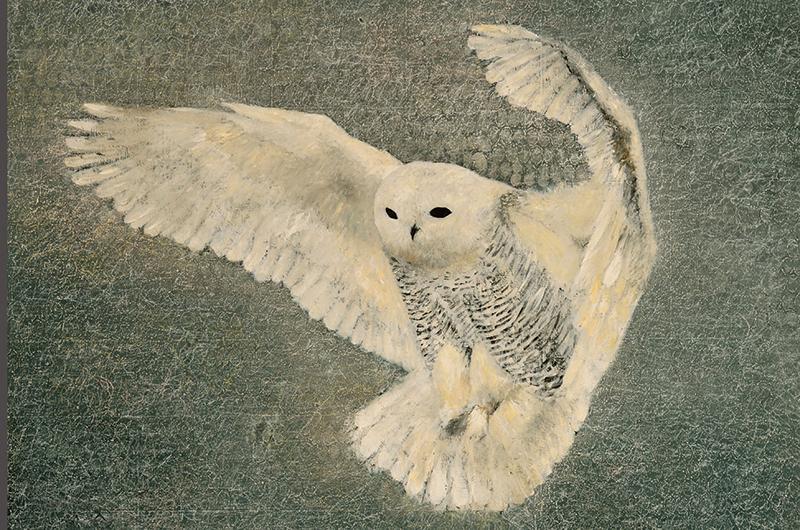

And what about those birds? This past winter Kane’s interest in birds shifted from the collective to the singular, as a result of coming nose-to-beak on two occasions with a certain snowy owl.

“Seeing the snowy owl,” she recalled, “it changed my relationship, my process – at least temporarily – of painting birds. When I paint birds, they’ve always been more about energy, about migration patterns, about flow, and design. The birds were collectively making a pattern. But when I saw this bird in nature, it was this iconic image. And they’re so spectacular. To see one of these creatures in nature is truly mesmerizing.”

Whether the owls of winter will return next year is anyone’s guess. But it’s safe to say that winged creatures will continue to feature in Kane’s work. After all, from the very beginning, they’ve played an integral role, not just as fleeting motifs in flight, but also in her process.

“Birds have just been part of the visual repertoire that helps train my eye,” she remarked. “The way some people paint the figure, every day it’s their artistic training, their meditation. For me painting birds frankly has quite often been when I don’t know what else to do. They are a homeland.”

Cindy Kane’s show Wing to Wing will be at the Martha’s Vineyard Playhouse in Vineyard Haven from August 23 to September 6. All season her work can be seen at the A Gallery in Oak Bluffs, and selected works will be on view at the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury. She is also represented by Graficas Gallery on Nantucket, the Lora Schlesinger Gallery in Santa Monica, California, and Cross MacKenzie Gallery in Washington, D.C.