Dirt roads on Martha’s Vineyard are character building. Traveling down a two-mile stretch out to Quansoo requires finesse and patience. Bump, swivel, glide. When finally you reach the tall grasses of the open outwash plain, your body still humming, the expected quiet of nearby Black Point Pond is broken by the din of waves. Though only a sliver on the horizon, the ocean sounds feet away.

Here stands one of the oldest houses on the Island – and quite possibly the oldest, if a recent Chilmark town document dating it to 1655 is to be believed. But the home, named the Mayhew-Hancock-Mitchell House for its previous owners, is much more than an artifact from a single moment in Island history.

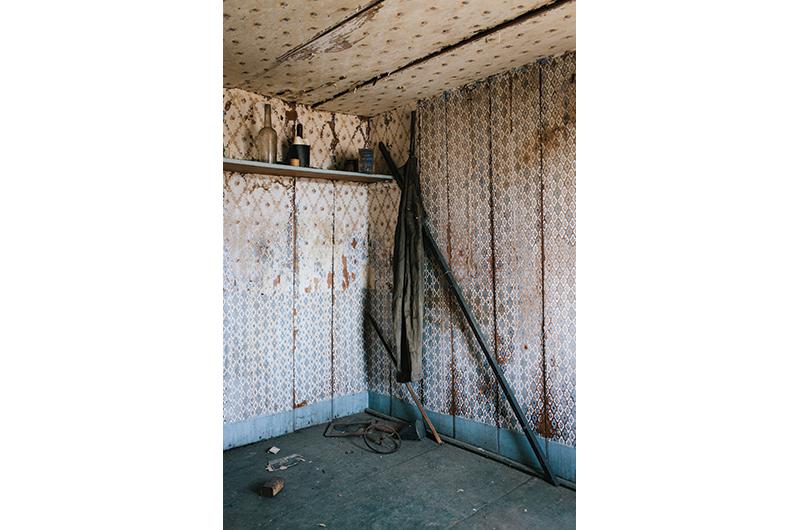

Inside, three centuries of history jumble together: straw-filled walls from the seventeenth century, wallpaper from the eighteenth century, a can of still-red tomatoes that has been displayed on a counter for an indeterminate amount of time. Additions undertaken over the years speak to the home’s history as a farmstead, a meeting house, and a seaside retreat.

“You can imagine yourself being here in the 1600s or 1700s. It probably hasn’t changed much,” says Adam Moore, executive director of the Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation, which received the property along with 156 acres in 2007 from the estate of the late Florence (Flipper) Harris. “It was probably a farm and looked very much like this. You can imagine why they built a house here, because it was pretty good land and there were a lot of natural resources available, including the pond and the ocean.”

Moore and Sheriff’s Meadow have spent the past several years bringing in experts to shine light on the home’s history. A dendrochronologist was enlisted to take core samples of the wood and examine tree rings in order to more accurately date the house — a process that proved inconclusive. Other specialists analyzed, or will analyze, shards of pottery, flakes of plaster, and scraps of wallpaper.

A major restoration of the house is expected to begin this fall, using historically appropriate materials and techniques. When complete, Sheriff’s Meadow will host educational programs onsite that illustrate the background of the property. But for now, the house sits relatively untouched — a moldering time capsule in a far-flung corner of Chilmark. For the lucky visitor it offers a chance to walk through the walls of history, seeking clues and reverberations from the past in the 350 years of architecture, details, and design.

Beginnings

The original walls of the house are packed with dirt and grass, using an ancient technique known as wattle and daub construction. Though once common, today only four wattle and daub structures exist in the United States.

“It was an English building technique,” says Moore, pointing to the weaving of rods and the compacted mud and straw. “But really, they were just using the material on hand.”

As the rarity of wattle and daub houses attests, most weren’t designed to last through several generations, never mind several centuries in an exposed location. What sets this house apart, says Moore, is the use of “hurricane” braces built directly into the walls.

“This is why this house is still standing. All of these diagonals, they go in between and are fitted into the post or stud to strengthen it.”

It helps that the nails attaching the boards to the beams also have held up. Amazingly, the iron nails and hardware in the seaside home are in near-perfect condition. Each nail was made of wrought iron harvested from bog ore on the Island, says Moore, and the iron was worked like dough and imbued with charcoal, making the metal stronger and more resistant to corrosion. It was such a tedious process that when people moved from location to location, they would often burn down the house in order to take the nails with them.

“What I would really love to do is make more iron from one of the bogs here,” Moore says of the restoration project. “There are even some stories about bog iron on Martha’s Vineyard being used to make cannonballs for the USS Constitution.”

Getting Plastered

Though unrecognizable in their current form, horse hair and oyster shells cover these walls. Brian Cooper, whose Connecticut-based company Early New England Restorations is leading the restoration project, says in order to create plaster, thousands of oyster shells would have been slowly burned in a kiln. The original owners used an oyster-burning kiln to create mortar for the foundation and the chimney at the time of construction, so it’s possible that plaster was made at the same time. But that’s unlikely, says Cooper. Plaster was a luxury item, requiring not just countless oyster shells, but also a huge supply of dry firewood. The first coats of plaster may well have been applied years or decades after initial construction, therefore, after the family was established in their new home.

Visible layers in the plaster indicate that additional sections of the home may have been covered over time.

Sheriff’s Meadow has sent out a sample for testing to determine the right balance between lime and acid needed to match the original plaster formula. Moore says he would like to build a kiln and hold a twenty-four-hour burn to make new plaster from shells collected from the Tisbury Great Pond and nearby Quansoo Beach.

Moving On Up

Green glass jars line the shelves, neatly set up and ready for canning. But one is already full. A jar of tomatoes has retained its bright red color after being brought up from the cool cellar below the house. This room is the buttery, which was added on during the eighteenth century and served as a pantry for storing food and dishes. It was intentionally located on the north side of the house so as to be out of direct sunlight. It was also a place to display the good china; grooves in the shelves kept pieces from slipping and falling.

Near the buttery and sitting room is the borning room. Here, young generations of Hancocks and Mayhews may have come into the world, or later daydreamed while their mothers kept house. This kind of small room is traditionally found in old houses adjacent to the living room or the warm kitchen. Original wooden hardware still operates to open and close the door. The wide wood paneling apparently provided plenty of entertainment for the youngsters. “The neat thing about this room is the wall with the ship carvings,” says Moore. He thinks it’s possible that children saw a ship passing by, or that their father was a captain of a ship and had gone to sea.

Similar scenes, circular designs with drafting compasses, and signatures can be seen on wall panels throughout the house. According to a study of the house by historian Jonathan Scott, an engraved drawing on one wall may represent a type of ship sailed by one of the original owners, Captain Samuel Hancock. There’s also a signature from West Mitchell, a captain involved in an 1871 whaling disaster in which a fleet of ships became trapped in Arctic ice. The name Hancock, written in perfect cursive, is visible on the inside of a closet door.

Revolutionary Wallpaper

The eighteenth-century parlor was once decorated with blue and white floral wallpaper, a light green trim, and a hefty fireplace. Today, only shards of the pottery and remnants of the intricate wallpaper remain, but the sense of grandeur is still apparent.

“This is a fancier room,” says Moore. “Perhaps they had more money and put in this really nice panelling.” The beams in this room are also covered with a finished molding, a style that was more expensive than leaving them exposed, as in other parts of the house.

Analysis of the multiple layers of wallpaper to date the designs has not yet been completed. At the earliest, however, the wallpaper comes from the eighteenth century, since that is when it first appeared in America.

Shipments of wallpaper were mostly delivered from England and France at that time. American production began to pick up after the Revolutionary War.

Ceramics in the room are easier to date. According to a report issued by Amanda Lange, a curator of historic interiors at Historic Deerfield Inc., the earliest piece – a mochaware bowl with creamware body – dates to 1800 or 1810. Shell-edged pearlware plates come from 1820 or 1830, she says, while a similar painted-rim style likely dates to 1850. A painted pearlware bowl with strawberries likely comes from 1810 to 1820, and an older yellowware mixing bowl with a seaweed-like decoration originated in the 1860s or later.

Up in the Attic

A roof is in many ways the very definition of a house. Appropriately, perhaps, the roof at the Mayhew-Hancock-Mitchell House is unusual for ancient reasons. All the roof boards run parallel to the rafters, from the eaves to the ridgeline, rather than the traditional perpendicular structure. Cooper, the historic preservation specialist, theorizes that this style was originally based on thatch-style roofs and was copied with the various additions of later centuries.

The top floor was used as a living space over the centuries, says Moore. It’s easy to tell why. It’s warm up in the attic of the house, even on a cold winter day.

Sun pours into the post-and-beam room. But there is at least one mystery. Each carefully cut joist and beam has a hand-carved Roman numeral on it – I, II, III, and V. It’s remarkable workmanship in any era.

Why the builder skipped the number IV, however, is lost to history.