As I pulled up to the Braley’s Way landing on Edgartown’s Eel Pond in pitch-black darkness, I didn’t like what my headlights revealed. The wind was out of the north, as predicted, but the whitecaps told me it was blowing fifteen knots at least, rather than the forecast five to eight. Whitecaps in the pond meant the seas outside the barrier beach would be choppy, steep, and breaking.

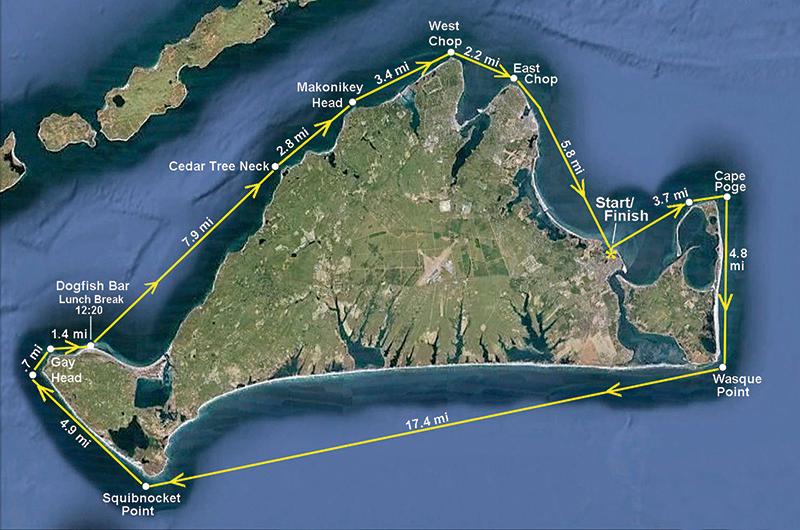

These were not the calm conditions I’d hoped for earlier in the summer, when I made four lengthy outings to assemble a course of twelve waypoints which, if followed successfully, would lead us all the way around Martha’s Vineyard – a distance of fifty-five miles – in a single day. I hurled a stream of invectives at the weather gods, who simply blew them somewhere offshore. Still, this was the appointed hour, and at least the late September air was warm. I turned on my headlamp and unstrapped the kayak from the car.

Headlights signaled the arrival of my compatriots, John Karoff of Milton and Tucker Lindquist of Ipswich. Veterans of the New England open water racing circuit, we all have paddled extensively in wind and waves, but none wanted to paddle tippy boats into waves we couldn’t see coming. We gave the ill wind its due, therefore, and delayed our 5 a.m. departure by forty-five minutes, when the first light of dawn would be breaking. At last, with the faintest glow in the eastern sky, we crossed Eel Pond to the tip of the barrier beach, our official start and finish line. I hit the START button on the GPS. We were off.

The idead of kayaking around the Vineyard in a single day first occurred to me after racing the kayak component of the 2007 Martha’s Vineyard Challenge, the legendary round-the-Island wind-surfing race founded by champion windsurfer Nevin Sayre of Vineyard Haven. Sadly, the Challenge is no longer run, but it got me thinking about going the distance with paddle power. I began studying nautical charts and calculating distances, speeds, and times. Most critically, I pored over the Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book.

I like to think of Nantucket Sound as a huge tidal pond that fills and drains through three main conduits: Vineyard Sound (between the Vineyard’s north shore and the Elizabeth Islands), Muskeget Channel (between Chappaquiddick and Nantucket), and Great Round Shoal Channel (between Nantucket and the elbow of Cape Cod). In every cycle the rising tide pours in for six hours through these three channels at about two to three miles an hour, with even higher speeds around points and headlands. Then the tide turns, and for six hours all that water flows back out from whence it came. Since kayakers paddle at speeds of four to five miles an hour, it’s critical to time long passages with favorable tidal currents. Put simply, you want to go with the flow.

We planned to leave Edgartown on a pre-dawn high tide, and go clockwise or counterclockwise around the Island, depending on the day’s wind conditions. In either direction, if we didn’t reach critical points in twelve hours – West Chop if clockwise, Wasque if counterclockwise – we’d face a debilitating foul current for the final eight miles of the trip. With the prevailing summer wind from the southwest, I assumed we’d take the counterclockwise route to avoid head winds in the twenty-three miles of open Atlantic along the Island’s south shore. Despite thirty years kayaking local waters, that leg was, for me, the wild card – a stretch I’d paddled for the first time only two weeks before. Going counterclockwise, I imagined us happily passing Squibnocket Point and cruising toward Wasque with a summer’s afternoon breeze at our backs.

But September 22, our chosen day, was also the first day of fall. With it came the churlish north wind and a decision to take the clockwise route. At least the south shore would be in the lee, and we’d face the long, risky segment early, with fresh arms. If the wind behaved and shifted to a light southwest, as predicted, we should have a dream-like afternoon paddle up Vineyard Sound. That is, if we could maintain the intended pace.

After a bumpy crossing of Edgartown’s outer harbor, we rounded Cape Pogue straight into sea kayaker’s heaven. The northerly tail wind and following seas gave us a surfing push, while the current ebbing strongly down Muskeget Channel added another two knots to our speed – but not without peril. Whether it was due to lack of coffee or a rogue wave, Tucker capsized and took a refreshing swim. We quickly helped him re-board and resumed our adventure – hoping that would be the only unplanned dip of the day. We zipped along East Beach with numerous fishing boats to our left and determined surfcasters on the shore to our right. Best of all, since the tide and wind were working in concert, there was no treacherous rip as we shot past Wasque Point at 9.5 miles per hour. With the capsize delay more than made up for, we turned the corner into the Atlantic proper, which was as calm as the proverbial millpond.

The south shore of the Vineyard, when viewed from the ocean, presents a long, low, unbroken strand of beach with a featureless backdrop of scrub oak woods. Behind the beach lie exquisite coastal ponds and expansive tracts of grassland; from offshore, however, it all looks the same. We might have seen the familiar up-Island landmarks – Abel’s Hill, Squibnocket, Wequobsque Cliffs – but as the shoreline to our right slid further away, it disappeared in a gray mist. I reassured my companions that we would indeed find land ahead. In a trance-like state, we paddled on, feeling the rhythmic lift of sizable ocean rollers, which I knew would be welcomed by the surfers we couldn’t see in Squibnocket Bight somewhere up ahead to our right.

All mariners keep an eye out for a sudden bad turn in the weather, but just as often, the turn is the other way, and reassuringly it began to clear as the cliffs of Squibnocket Point shimmered into view dead ahead. Summer turned officially to fall at 10:49 a.m. as we passed the point on surfable swells, and we tucked in close to the beach under the great sculpted dunes. Next, the dramatic southwest rampart of the Gay Head Cliffs appeared five miles ahead, and I crunched numbers in my head: It was eleven o’clock and the tide was just beginning to flood into Vineyard Sound – perfect. That gave us five hours of favorable current to reach the final headland of the route, East Chop.

The clock was ticking, but no matter the timeline, one simply cannot hurry past the Gay Head Cliffs in a kayak. The scene is so spectacular, the setting so unique, the scale so overwhelming, that the paddler must stop, look up, and marvel. We drifted along in awe, taking photos as the current swept us past boulders crowded with gulls and cormorants.

Dogfish Bar was our planned lunch spot, and at 12:20 p.m., with almost thirty-three miles tallied on the GPS and twenty-two left to go, we pulled ashore. With the wild-card ocean leg behind, I was happy to be back in familiar waters, but even better was the chance to stand up, stretch, and walk about. During lunch the clouds lifted, the sun broke through, and the sky turned a brilliant blue. In glorious early autumn sunshine, with the lightest puff of a southwest breeze at our backs, we set off again at 1:00 p.m.

Our live took us straight to Cedar Tree Neck, eight miles distant, which kept us well offshore but held us in the best current. It’s more scenic to hug the coast, but even from afar the wooded morainal hills, prominent bluffs, and boulder-strewn landscape of the Vineyard’s north shore were a happy contrast to the low, flat sameness of the Atlantic side. The sheer sand cliffs of Menemsha Hills Reservation, the remnant chimney of the brickworks ruins rising from the hollow just beyond, the great boulders waiting to tumble from the scarps past Cape Higgon: These are a side of the Vineyard that non-boaters rarely get to see. My off-Island friends were amazed by the rural quality of the landscape.

Equally amazing were the speeds I saw on the GPS: We rode the tidal river northeast toward West Chop at more than seven miles per hour. With the lobster pot buoys dragged under by the current, we positively cruised past Cedar Tree Neck, Paul’s Point, and on toward the steep sand face of Makonikey Head. Off Lambert’s Cove, the current abated and I knew we’d seen the best of it, but with West Chop now in view, it was just two more right-hand turns to the home stretch.

The green buoy off East Chop stood straight up in the water as we passed – a sure sign that the flood tide was slack, and just about to turn against us. But with weak currents at the beginning of each cycle, we’d beaten the worst of the ebb as we rounded the corner. The Oak Bluffs Steamship Authority pier came into view, and beyond it, in the far distance, tiny white blocks against a green backdrop signified the stately houses overlooking Eel Pond. The end was in sight!

Weaving between the pilings of the pier, I knew from scores of training workouts that the straight line to our finish was exactly 4.7 miles. The normally brisk afternoon southwest wind, which might have made for extra work and forced us to hug the shore for shelter, was uncharacteristically benign. Side by side now, we glided past familiar landmarks as we paddled the offshore line: Farm Pond, Harthaven jetties, and then the arc of State Beach, with little bridge, big bridge, and the lifeguard stand at Bend in the Road Beach.

I knew we were closing in on eleven hours paddling time, but I fought the urge to look at my watch. This was never meant to be a race, after all, but an expedition. It was purely for the record therefore, that after crossing the shoals outside Eel Pond I paddled my bow right onto the tip of the barrier beach and hit STOP on the GPS. We’d gone exactly fifty-five miles in just over eleven hours of paddling. Dismounting and standing up exultantly, my left leg immediately cramped and I keeled over face first into the shallows – finished, in every sense of the word.

It was just past 5:30 p.m. on a warm, sparkling, first-day-of-autumn evening. We had set out from this very same point twelve hours earlier into darkness, bumpy seas, and a brisk northerly wind. But the day had been perfect. The weather gods had proven to be benevolent after all, and we were back where we started.