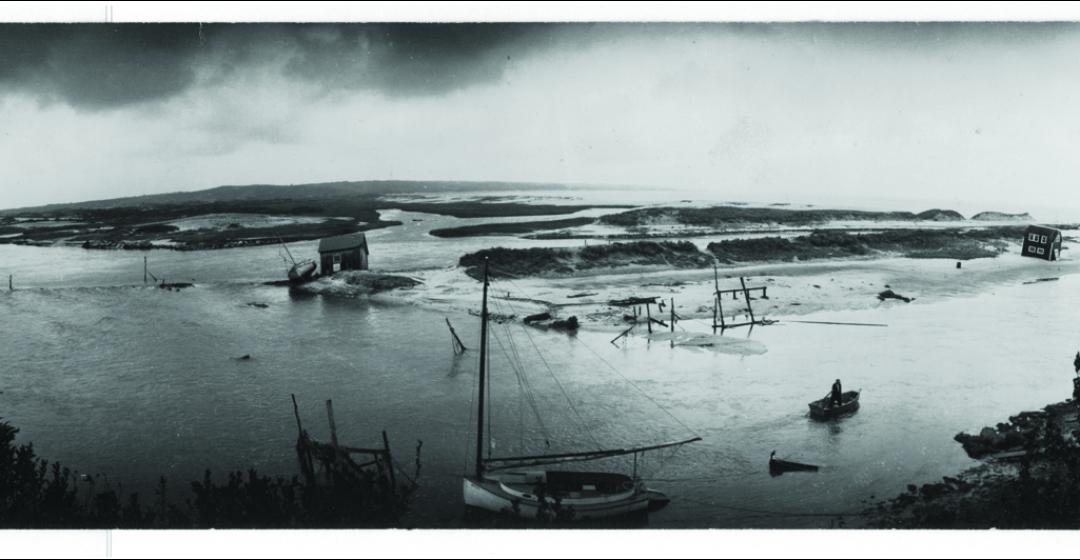

In the Northeast, it is considered the great storm of the twentieth century, a hurricane that came crashing up the Eastern Seaboard without warning on September 21, 1938. Every town on the Vineyard took a ferocious pounding that day, but the little fishing village of Menemsha was essentially destroyed. The men and women who remember that afternoon were hardly more than children when they saw Menemsha swept away.

Everett Poole, who would grow up to run a fish market in the village, was nearly eight years old; he struggled to make out what was happening from a hilltop as his father and grandfather, who were caught in the harbor trying to manage a dory with a broken oar, were swept into the gray-green murk of the storm.

Jimmy Morgan, now a retired fisherman, was fourteen. He stood on the porch of his grandmother’s home not far from the harbor and heard his father say, “Everything I worked for is going.”

His friend Louis Larsen, also retired now from fishing, was twelve. Louis was with his father, Dan, and older brother, Bjarne, aboard the family fishing boat, the Francis J., which was tied up in the harbor basin. Driven by the inrushing storm surge, another boat had pinned the Larsen boat against a pier, and a wooden stake had smashed a hole through the bottom.

With father and sons still on deck, the Francis J. broke free and hurtled over the top of a sand spit, which normally lay eight feet above the high tide line. The engine was dead, the boat was sinking, yet as the stricken vessel rocked up the channel with the ruins of the village heaving alongside, the boy marveled at how calm his father was.

“We’ve got water coming in the boat here!” yelled Louis over the wind. The sea was carrying the vessel into the gale, which was whining against them from the south at between seventy-five and a hundred miles an hour. “‘Well, there’s nothing we can do about that,’” Louis remembers his father saying. “‘We’ve just got to make sure we drift up somewhere where we’re safe.’”

The Francis J. came to rest partway up the hill behind where the US Coast Guard station stands now. Today, seventy-five years after the Great New England Hurricane backhanded the fishing port of Menemsha off the face of Martha’s Vineyard – leaving behind nothing but open water and sand across what had been the old waterfront – you can still see a dip in the hill. This is the remnant of a trench dug to drag the Francis J. back down to Menemsha Creek.

The early days of Creekville

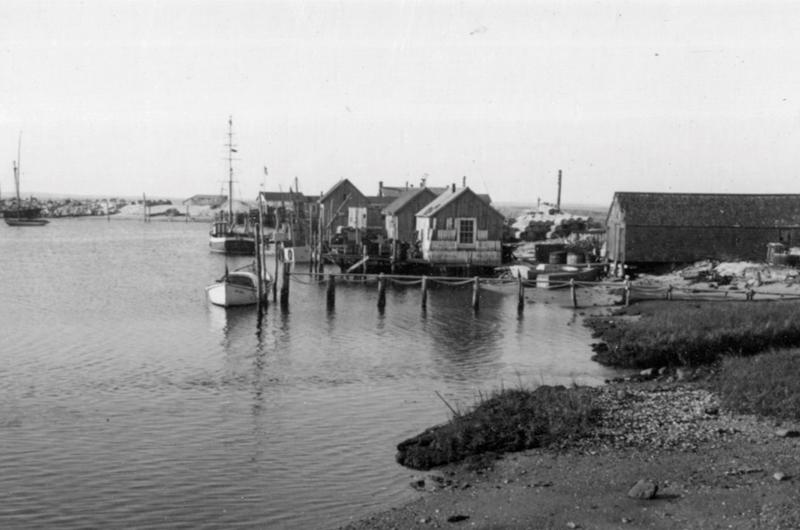

Menemsha, with its weathered exteriors, looks like the oldest village on Martha’s Vineyard. Shingled boathouses, shacks, and wharves jumble high and low along the harbor. Roads and homes lie in pleasing deference to shrubby hills, shorelines, and marshland.

But Menemsha is brand new compared to other settlements on the Island. Except for the stone jetties that keep the channel entrance open to Vineyard Sound, just about everything from the Coast Guard station out to the beach, where throngs applaud the sunset most every summer night, was built from scratch following the hurricane and storm surge.

Menemsha of the 1930s was also newly built and largely engineered by man. At the start of the twentieth century the place had been known, evocatively, as Creekville, and that’s really all it was in 1900: a clutch of buildings that lay along a shallow creek that meandered through lowlands and hills in a gentle arc from Vineyard Sound to Menemsha Pond, three quarters of a mile inland.

Nobody lived there, wrote John Leavens in 1983 in The Dukes County Intelligencer, the quarterly journal of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum – though fishermen did keep dories and other small boats in the creek year-round. “The swift flow of the current scoured the east bank of the Creek as it curved past what is today the Bulkhead and Dutcher Dock, providing deep water,” wrote Leavens, “although space for mooring was limited by the narrow channel.”

But in 1903, to create a true, deep-water harbor for ocean-going fishing vessels, the state sent a sand sucker to dredge the bottom of the creek. The sand had to go somewhere, so the dredge pumped it onto the shore from what is now the Menemsha Texaco station back to Creek Hill, which overlooks the harbor.

Along the base of this new, rather long sandbank, fishermen such as Everett Anderson Poole and his son, Donald, as well as Ernest Dean and Rasmus Klimm, built boathouses and narrow piers from which they set out in their boats to harpoon swordfish, trap lobsters, and jig for cod.

With the hope that nearby Menemsha Pond might one day serve as an even larger anchorage for the village, the state also dredged a channel from Vineyard Sound south to the pond. It ran broad and deep and roughly parallel to the former creek, which had become the new harbor basin. The state built stone jetties at the entrance to Vineyard Sound to help hold the channel in place.

Sand dug from this new channel had to go somewhere too, so the engineers used it to build up a long sand spit, which divided the manufactured harbor basin from the engineered channel. Starting at about where the Menemsha Galley is today, the sand spit lay about eight feet above the high tide line, but it rose as the dredge piled up sand along the channel, so that at the far end, near the entrance from Vineyard Sound, it stood almost twenty feet above the water.

Along this spit, fishermen built more boathouses and, among other buildings, a fish market, a henhouse, and a card room called the Mystic Knights of the Sea, a name borrowed from the Amos ’n’ Andy radio program. With the work more or less completed by 1906, the fundamental assets of Menemsha were laid out from west to east: the new channel, the sand spit, the basin, and its eastern sandbank. To honor its transformation and link the growing village to the broad pond to the south, Creekville changed its name to Menemsha.

Three great waves

Dan Larsen, whose boathouse stood about halfway along the sand spit that separated channel and basin, had been watching the barometer all day, anticipating the weather. “He knew it was going to be a bad storm,” says his son, Louis. “But he didn’t realize it was going to be that bad. They never really knew about hurricanes in those days.”

A storm system near the Cape Verde Islands had coiled up the gale and sent it wheeling toward North America on September 10. By eight o’clock on the morning of September 21, it lay about 375 miles east of Cape Hatteras, its winds crying around the center at about 120 miles an hour. Suddenly it veered north and accelerated, its forward speed increasing to almost seventy miles an hour. It raced over Suffolk County, Long Island, just six hours later. Southern New England had not endured a great hurricane since 1869. There was hardly anyone alive who could imagine such a thing striking the Northeast.

“What you have to remember first is that nobody expected anything to happen,” Everett S. Allen, who grew up in Chilmark, wrote in his history of the storm, A Wind to Shake the World: The Story of the 1938 Hurricane (Little, Brown and Company, 1976). As the storm whirled northward, it destroyed the means to warn those up the road what was coming. “Communications, by land, sea, phone, telegraph, or teletype, were wiped out in those areas that had the most to communicate,” Everett Allen wrote.

Those who experienced the hurricane at Menemsha as youngsters recall that the village began to come apart as they were returning home from school. Jimmy Morgan remembers walking down the hill through wind and rain from the bus at about 3:30 p.m., the storm already bad enough to make him want to keep going up to the head of the basin to see how it was faring.

“The wind kept getting stronger and the tide kept getting higher,” he says. “There was a lot of old junk, old lobster pots, all kinds of derelict boats. So the boats started going adrift, so I says, ‘I guess I’d better get home.’” He walked to the home of his grandmother and step-grandfather, Rebecca and William Tilton, which lay at a bend in Basin Road, just back from the harbor.

Louis Larsen also remembers the wind beginning to bluster as he walked through the door to his family home up the hill, just off Larsen Lane. His mother, Kristine, told Louis to go down to the boathouse to help his father, Dan, and his brothers Bjarne and Dagbard, known as “Debba,” lift bags of salt from the floor onto the workbenches. The salt was used to preserve bait for lobster pots. When Louis reached the boathouse, the wind was already bullying, the rain stinging, and the water in the basin choppy, slapping up underneath the narrow pier to which Dan’s forty-foot fishing vessel, Francis J., was tied.

Father and sons were moving the salt when they looked up and saw the waters of Vineyard Sound submerge the harbor jetties. A moment later the tide came rushing through the door. “Like tidal waves, they were. One right after the other,” says Louis. It was this sudden smack of peril that amazes him even now. “You could see the breakwater,” he says, “then you couldn’t see the breakwater at all.”

What Louis was seeing was the arrival of the storm surge, which overwhelmed the fishing port in three great waves. The wind and rain had come first, beating at the village with rising force for much of the afternoon. But around 4:30 p.m. the wind began to shriek and, without warning, the three shoveling waves rolled unimpeded through the basin and channel, one after the other. It was this series of “tidal waves,” as everyone called them afterward, which brought the true destruction.

Another man, Raymond R. Cook, caretaker of the Hornblower property at Squibnocket, had seen this storm surge rise and roll in from afar. Raymond was standing on high ground about two miles south of the village. Looking out over the Atlantic, he saw “the great storm wave coming,” wrote Everett Allen.

“He said it was gray; from trough to top, it had a twenty-five-foot front, with spray and foam reaching ten feet above the actual wave…. [It] seemed to come broadside, sweeping down along the shore, and it was followed by a second and a third, neither reaching the height of the first.” These waves broke over the ocean-facing barrier beach and filled Stonewall Pond, then Nashaquitsa Pond, then Menemsha Pond, heading for the village.

There, from his grocery store at the head of the basin, Carl Reed was looking the opposite way. He saw the same three storm waves come at Menemsha, only these were rolling in from the Vineyard Sound side. Reed saw “first one, then a second, and last a third great wave sweep across the creek carrying everything before it,” reported the Vineyard Gazette right after the storm.

The surge hurtled southward through the channel, which had been dug invitingly wide and straight. The waves also raced into the harbor basin. The sand spit along the engineered channel and the sandbank along the dug-out basin were no match for these waves. After the third one bashed through, nothing floated or stood where they had been except for Carl’s store at the head of the basin and two boathouses on the sand spit, canted and broken.

A huge wall of water

From his home on the Menemsha Cross Road, Everett Poole had walked to the harbor basin shortly before the storm waves struck. Everett climbed the short, steep Creek Hill to the home of his grandparents Everett Anderson and Emily Poole. There he joined his grandmother and his mother, Dorothy. From the porch the three Pooles strained to see what was happening down in the basin where Everett’s father, Donald, and grandfather owned neighboring boathouses at the foot of the sandbank.

“It was just gray, with spray and rain flying all over the place,” remembers Everett, and it was good, perhaps, that the boy could not easily see what his father, grandfather, and Jimmy Morgan’s father, Clarence, were going through. Donald and Dorothy Poole later wrote it all down in the back of a diary belonging to Donald’s uncle, Chester Poole, and author Everett Allen recounted their story in his book.

With extra lines, the three men managed to secure the Anna W., a catboat belonging to the grandfather Everett, but when they moved over to lash down Donald’s catboat, the Dorothy C., they found the pier out to it already gone. Their path back to the footbridge, which connected the sandbank to Basin Road, was completely flooded. The three men boarded a dory and tried to row up the harbor to the footbridge. But as soon as they pulled away from the boathouses, “a huge wall of water swept over the breakwater and engulfed everything,” reads Dorothy’s account.

The sandbank collapsed, bringing down into the harbor basin all that had lain along the length of it – boats, shacks, piers, traps, nets, tools – everything that working men on that side of the harbor owned. In the miasma, surge, and howling wind, the dory carrying Donald, Everett, and Clarence managed to reach the footbridge, but an oar broke, another wave came through, and they were swept over the bridge into what had been marshland earlier in the day, but was now part of the stormy sea.

The men were carried a third of a mile over the flooded wetland toward the summer home of Leopold Mannes, an inventor of Kodachrome film. As they surged past the house, Donald reached and – with his fingertips – grabbed the railing around the porch, took hold, and pulled them to safety. Dorothy Poole could see which direction the current was taking them. With young Everett, she got into her car and drove around toward the Mannes house. On a dirt road beyond the Menemsha Inn, they met the three men walking home. Donald told his wife and son that had he missed that railing, the storm would have swept the dory out into the maelstrom of Vineyard Sound.

The Pooles drove Clarence Morgan to the Tiltons’, which lay across the street from Creek Hill, close to the water. Young Jimmy Morgan and his grandmother were there. The tide had reached the grass just in front of the porch. Standing with his son, Clarence said, “Everything I worked for is going,” and seventy-five years later, there is a hitch in Jimmy’s voice as he remembers his father’s words. Even at that hour, no one knew how much higher the water would come, so Clarence carried his mother up the hill, where she rode out the rest of the storm with the Pooles.

Trying to save the boats

After the first wave came through their boathouse, Dan, Bjarne, Debba, and Louis Larsen stopped their work and looked for a way to get home. But to their right, the waves were rushing over the sand spit like a whitewater river, trapping the Larsens at the boathouse. The surge was also tearing over the pier to the Francis J., so they couldn’t reach the boat either.

In this moment of danger, William Hand, a highly regarded naval architect whose boathouse lay a few buildings down the spit, appeared. William wanted to get out to his motorsailer, the Gossoon, which was moored in the basin and threatened by the wreckage that was bounding by it. His dory lay near the Larsen boathouse. The men worked up a plan. William would try to row out to the Gossoon. The dory would have a line attached to it so the Larsens could pull it back. Then the Larsens would use the dory to row over to the Francis J. and ride out the storm on something that could keep rising with the tide.

William made it to the Gossoon and the Larsens pulled the dory back. But just as they were about to set out for the fishing boat, Debba dove into the basin and began to swim for home on the other side.

Dan, Bjarne, and Louis were shocked, but there was nothing to do for Debba now, so the three men got into the dory and reached the Francis J. At that moment, Arnie King, a harbor pilot from Newport, came racing up the harbor in his own boat. It was clear that Arnie was going to try to rush over the submerged section of the sand spit near the Larsen boathouse. But he rammed the bow of the Francis J. instead, pinning it to the submerged pier, where the seas lifted and dropped the boat heavily onto a wooden stake, which punched a hole through the bottom that widened with every crunching wave. Water began to flood the fishing boat, killing her engine.

Suddenly Arnie’s boat let her go. The incoming flood carried the Francis J. and the Larsens over the sand spit and sent them heaving and foundering into the channel. So strong was the current that it overruled the howling wind, which was blowing from the opposite direction. The collision of these two forces, as the tide swept the boat into the gale, was apocalyptic.

“The seas were so tremendous,” says Louis. “I don’t know how my father could stand it, to know that everything he had was gone. Here the boat and everything was underwater, the engine underwater. You have to do what you have to do.”

But there came a moment when the keel struck hard ground on the east side of the channel. The Larsens jumped overboard with lines and anchored the vessel where she lay. The surge had carried them a fifth of a mile inland, leaving them on the side of the hill.

Louis’s mother, sisters, and brother Debba rushed down to greet them. Debba had indeed managed his swim through the tide, wind, and wreckage. He had joined the rest of the Larsen family atop Creek Hill. From there they had watched the Francis J. go swirling up the creek. “‘I knew you guys were going to get stuck back there,’” Louis remembers Debba saying when his father and brothers chided him for diving in. “‘At least I took a chance and did it.’”

The Francis J. was repaired where she lay and refloated. But it took a bulldozer, blocks, and tackle to drag the boat back down to the water. Walk around behind the Coast Guard station and you can still see the dip in the hill where they dug a trench to haul her back to the water seventy-five years ago.

Wreckage and repair

Daniel Greenbaum turned thirteen the day before the storm. He was a summer boy, living near the Menemsha Inn with his mother, Dorothea, a well-known sculptress, and his older brother, David. His father, Edward, an attorney in New York, was away at work that week and ended up taking a plane to Katama several days later, unable to reach his family by telephone. Dorothea took the boys to the south side of the Island to look out over the Atlantic while the storm whistled and moaned.

“We got down to the cliff, and I remember we were thinking it was so wonderful,” Daniel says. “You could lean right over and the wind would hold you up. My mother didn’t think this was such a wonderful idea.”

Then they drove to Menemsha to discover, literally, that there was nothing left to see.

“The surge had come through, and Menemsha didn’t look anything like what it had looked like before. The shacks were gone. Fishermen were standing around. And the only boat that they had saved, that they had pulled up the road, was our little sailboat. Still I think, you know, here they are with their livelihoods out there, and they save our little sailboat,” remembers Daniel.

Daniel, David, and their mother walked down as far as the Tiltons’ house, but got no farther. The footbridge to the sandbank was gone, and the wetland over which the Poole dory had been swept was still “one huge lake out to the right. With no land, it was all water. And of course at this point the water had probably gone down eight feet from where it had been,” says Daniel.

The three waves that Carl Reed saw come through the jetties had raked nearly everything off the sand spit from the tip back to the head of the basin – the fish market, the henhouse, the Larsen boathouse, and the card room, among other structures, as well as every pier and boat. What was left was nothing more than a sandy hump in the middle of an open waterway with two ravaged shacks remaining. The basin and everything that stood along the old sandbank was entirely gone. Those who had seen it all go witnessed or inferred incredible things.

Louis Larsen saw the Madeline, a fishing boat belonging to Reginald Norton, roll out toward the Sound as one wave of the surge retreated. “It went up over the breakwater and it came down right on the breakwater and disintegrated,” he says. Donald Poole wrote that his father’s catboat, the Anna W., “went adrift up the pond, with my little boat in tow. His boat ran into his own boathouse and went right through it like paper.”

Along the shorelines and up in the fields lay fishing boats, parts of boathouses, fragments of piers. The village had been “wiped as clean as a slate is washed,” said the Gazette. Everett Anderson Poole told the paper: “It’s bad, mighty bad, but when you go out to probe in the rubbish to see what can be saved, you don’t have to dread uncovering the body of your dead brother.”

The Gazette began a Fishermen’s Fund to aid those who had lost everything and to rebuild the harbor. Though the Depression lingered, the fund topped out at almost $13,000 (roughly $200,000 today). With $350 from the American Red Cross, Dan Larsen repaired the Francis J., replaced a hundred lobster pots he lost in Vineyard Sound, built a new boathouse, and had money left over. Daniel Greenbaum’s father and influential friends who summered in Menemsha helped secure state and federal funding to build what today is the bulkhead along the basin and Dutcher Dock, where recreational boats tie up, as well as the wharf that replaced the sand spit.

And so, as it had been in the first years of the twentieth century, Menemsha was once again built from scratch.

“The most encouraging aspect of the whole matter is that Menemsha always was genuine,” read a Gazette editorial as the work began that autumn. “Whatever is built will be built simply and directly, and there will be enough lobster pots, net, cordage and other gear around to link up the new with the old….We hope the result will be what everyone desires, a community at the creek which will attract and hold the affection of all comers as the old Menemsha did.”

That is the way things turned out. But along the rebuilt basin and creek, memories linger. “To my eyes, to this day, I thought it was the end of us,” says Louis Larsen. “I just don’t know what would happen today, if it ever came to that, because everything’s so expensive to repair and rebuild today. I hate to think of it. I hope it never happens again.”

A harrowing Escape in Edgartown

Francis E. “Sandy” Fisher was working on a catboat off Wasque Point on Chappaquiddick when the skies darkened over the ocean and the wind dropped away to a deathly nothing that Wednesday afternoon seventy-five years ago. He was twenty-two years old then and is ninety-seven now, the oldest retired fisherman in Edgartown. He remembers how the Great New England Hurricane came upon Edgartown harbor from the south.

Sandy was part of the crew aboard the catboat Hortense that day. They were dragging for moon snail eggs in the channel at Wasque, part of a Work Progress Administration (WPA) project to help protect quahogs from predation. The captain of the Hortense was the owner, Joe “Two-Tail” Bettencourt, so nicknamed because he once claimed that he had seen a rat with two tails.

But the man really in charge was WPA foreman Pat Delaney, “an old-timer from the south of Ireland,” who wasn’t a fisherman himself, recalls Sandy. The crew included Henry M. “Buddy Uke” Minstrel, Manuel Perry, Charles A. Fisher, George R. Searle, and Marshall M. Pease. Three of Sandy’s brothers-in-law were also aboard: Benjamin Gross, Philip “Blackie” Grogan, and Gus Blankenship.

Some of the men began getting uneasy as the seas were coming up. “So they told Pat, says, ‘Geez, things don’t look too good, Pat.’ It was starting to get dark, you know. It comes right calm. You see that sky get that way, something’s gonna happen.” But in September, 1938, few believed a hurricane could strike New England, and no forecast had warned that this storm was coming.

Then it “started to breeze up a little bit,” says Sandy. The crew kept looking to the south as the sky blackened and the sea began to menace the ocean-facing barrier beach that lay between the boat and the Atlantic. Still, Pat Delaney refused to give the order to head for home: “‘Ah, a little sou’easter,’ he said. ‘Ain’t gonna bother.’” Then things turned serious. “In the matter of an hour – oh my God, it was terrible,” says Sandy. “I guess he finally said, ‘Yeah, we’ll go.’”

With the one-cylinder Lathrop popping along, Bettencourt pointed the Hortense for Katama Bay, the broad, shallow waterway they would have to cross first. Ahead of them, two and a half miles to the north, lay Edgartown harbor and home. “By the time we got to the narrows of the harbor there – oh my God,” says Sandy. The catboat was built wide to carry loads of fish and stay stable in a rough sea, but now it was riding great ocean waves and slewing left and right in the troughs. The wind, rain, and spume were thundering at them from astern at a hundred miles an hour or better.

When it reached the head of the harbor, the Hortense made a try for the Edgartown Yacht Club wharf; in the lee of the yacht club building stood Eldridge’s Fish Market and a pier to which they might tie up. But “we couldn’t land on that side,” says Sandy. “Everything was breaking right over the roof of the yacht club. You can’t land in that.”

Desperate, they turned hard to the right, following wind, tide, waves, wreckage, and castaway boats toward the harbor entrance. On their right they saw the ferry slip on the Chappaquiddick side of the harbor. The ferry City of Chappaquiddick had sunk in the slip, so Bettencourt steered for the wharf and drove his boat as purposefully as he could into the slip, landing the boat on Chappaquiddick Point.

The men clambered out of the boat onto the shore. The seas were knee-deep, hauling and shoving them like a river, and the wind blasted them mercilessly, but they managed to struggle up the road to a hill looking down on the point. On it stood Menaca Hill House, a rustic inn run by Edith “Deedie” Smith (who would become Edith Alger in marriage). The men climbed the hill and pounded on the door, relieved to have found shelter.

The crew spent the night at the house, under the care of Edith and her employees, and it wasn’t until midday that it was calm enough for them to leave.

When Sandy and his fellow fishermen returned to the harbor entrance, the Hortense “was smashed to pieces, right on the point there.” They found skiffs and rowed toward the splintered Edgartown waterfront, where boats had pierced boathouses, buildings were gutted and toppled, and lumber carpeted the waterfront streets.

“Oh, that Edgartown waterfront was terrible,” says Sandy. “Wicked. Boy, what a beating.” But there wasn’t much time to wonder at it, he adds. He and the rest of the men were earning roughly thirty cents an hour from the WPA program. While the Depression wore on, there was only one mandate for all of them: “Get back to work and get some money.”

Sources for this story include Chappaquiddick: That Sometimes Separated but Never Equaled Island [second edition], edited by Hatsy Potter, Chappaquiddick Island Association, 2008.

Death at Stonewall Beach

Given the lack of any advance warning of the 1938 hurricane, it is remarkable that only one person on Martha’s Vineyard died in the storm. Yet it is also a singular tragedy that the victim, a cook from the Caribbean, had sensed the danger coming that day.

She was Josephine Clarke, thirty-eight year-old mother of two children, who came from Jamaica. We know almost nothing more about her, save for the way in which she died. There are three versions of what happened that day, and there would surely have been a fourth had Josephine lived.

Her employers were Benedict and Virginia Thielen (pronounced TEE-len). He was a respected writer; she was an artist who showed in New York and Paris. They owned a winter home in Key West and a summer house in Chilmark, one of several that stood behind a row of dunes on Stonewall Beach, which faces the Atlantic Ocean.

The Thielens and Josephine had a front-room view as the great storm rolled in. Divergent accounts of what happened next have been recounted in several published articles and books.

In her self-published 1989 memoir, Virginia’s Journal, Virginia describes Josephine bringing in the tea at four o’clock. The Thielens were on the couch in their living room, “watching the surf pounding the beach below. The gray sky was full of racing clouds blown north by whistling gale winds, yet it was too warm for a fire on the hearth; in fact, the air felt almost tropical.”

Josephine, who knew of these storms in Jamaica, said to her employers, “Hurricane weather.” But Virginia wrote that she dismissed the idea: “Don’t worry....The water won’t come as far as the house.” Her confidence came from a conversation she had had with Chester Poole, a Menemsha fisherman, who told her that only twice in his lifetime had the water come up as far as the dunes in front of them “and no further.”

According to Virginia, Josephine left the room, “shaking her head.”

Watching the sea and sky, the Thielens discussed the time of high tide, how the grass was being blown flat on the dune and “shivering in the wind.” A gust hit the house hard, and Virginia cried to her husband, “Ben, look at that yellow tinge in the sky.” He replied, “You’re not worried, are you?” and patted her hand. Soon he went outside to take a look around. “The wind,” Virginia wrote, “kept howling and booming; it sounded like oversized kettle drums, playing wild crescendos.”

Charles Close, Ben Thielen’s stepson, reports a different story, recounted by Niki Patton of West Tisbury in an article for this magazine a decade ago (“The Flight of the Thielens,” September–October 2003). According to Charles, Ben proclaimed that, “It smells like a hurricane,” and then warned the women that they needed to leave. Why his wife and employee refused to heed this warning is left unexplained. Ben’s own account, originally published in The Yale Review (and later published in Reader’s Digest and excerpted in A Wind to Shake the World) focuses on what happened next.

He describes the yellow flecks of foam flying over the dunes toward the house from the sea. “It looked like the vomit foam of a sick animal,” he wrote. He tells of the water rising, first slowly, and then with a power that brought rocks and boulders thudding against the foundation. The Thielens decided to leave. With Josephine, they went to the back porch, stepped into a foot of water, and began to walk toward high ground through the rising flood. Virginia was walking ahead, with Ben walking more slowly and holding Josephine’s hand.

“But now the tempo of the sea and tide changed. There was no slow, gradual increase of the water. There was a swirl and a noise of rocks and splintering wood, and the water was up to our waists. There was a second wave and it up was up to our necks. Josephine could not swim. I held on to her. Something huge rushed from the beach, and the water rose above our heads,” he wrote. Ben, Virginia, and Josephine were swept into Stonewall Pond, on the inland side of the barrier beach where the house stood.

Shifting to the present tense and taking the reader with him on the wave, Ben keeps hold of Josephine’s wrist with one hand, “but my boots are filled with water and I can’t kick to swim. My sweater is like lead on my arms, and my oilers are stiff and heavy with the cold….

“There is a screaming in my ears of this sinking woman and the wind blowing at ninety miles an hour – across the water where there was once land. I know about lifesaving and try to swim backwards holding her with one arm on my chest. I cannot move my legs with water-filled boots. To get them off, I must submerge completely, lean down, and pull at each one with both hands. I must let go my hold on this dark reaching hand….I see the dark face sink in the water, then rise again.…” Free of his boots, Ben reaches back for Josephine, but the hand and face are gone. “A woman’s hat with a green feather is floating, spinning slowly around in the water.”

Ben and Virginia Thielen swam and reached the shoreline of Stonewall Pond. Thomas Hart Benton, the artist, who lived nearby with his wife, Rita, met them there. The Bentons had seen everything and Tom had come to take the Thielens to his home. That night, in bed, “we clung to each other like frightened children,” wrote Virginia. “Ben cried at his failure to save [Josephine] and I tried to persuade him that it was not his fault. We slept at last from exhaustion.”

Remarkably, the Thielen house had floated nearly intact across Stonewall Pond to the place where Ben and Virginia had come ashore – “testimony to the acumen of Island carpenters and perhaps to the seaworthiness of a well-built Vineyard house,” wrote Niki Patton. (There had been other houses and camps on Stonewall Beach, but these were all reduced “to matchwood,” reported the Vineyard Gazette.)

From Bernetta Parker, the Thielens bought the land where the house had come to rest. Oxen pulled the house up to high ground, and the original builders, Roger Allen and Clifton Parker of Chilmark, rebuilt the living room and chimney and repaired the rest of the damage. The house stands there still on a rise called Anchor Hill.

Virginia later divorced Ben Thielen and retook her maiden name, Berresford. Both Tom Benton and Virginia painted dramatic landscapes of what Benton would call the Flight of the Thielens, his work showing the grotesque tumult of the incoming sea, and hers showing vast expanses of white, a rendering of the obliterating flood and foam through which she swam to reach the shoreline of the pond.

The body of Josephine Clarke was found the following day near the wreckage of the Hariph’s Creek Bridge. Her remains were shipped home to Jamaica. Benedict Thielen died in 1965 at the age of sixty-three, Virginia Berresford in North Tisbury in 1995 at the age of ninety-three. She had lived on the Island year-round since 1952.