With a lifelong interest in archeology and prehistoric art, Duncan lectures on subjects such as “The Saharan Origins of Ancient Egyptian Royal Symbols” and “Western Saharan Sculptural Families and the Possible Origins of the Osiris-Horus Cycle” in places as diverse as the Explorers Club in Manhattan, the Musée National de Préhistoire in France, and the Aquinnah Public Library.

His summer home in Aquinnah, which he designed and helped build, is beautiful and strewn with treasures from a lifetime of travels in Mali, Portugal, Tunisia, and Morocco. In conversation, he trots the globe and travels back in time. “Every place in the world is exotic if you begin to scratch the surface,” he says.

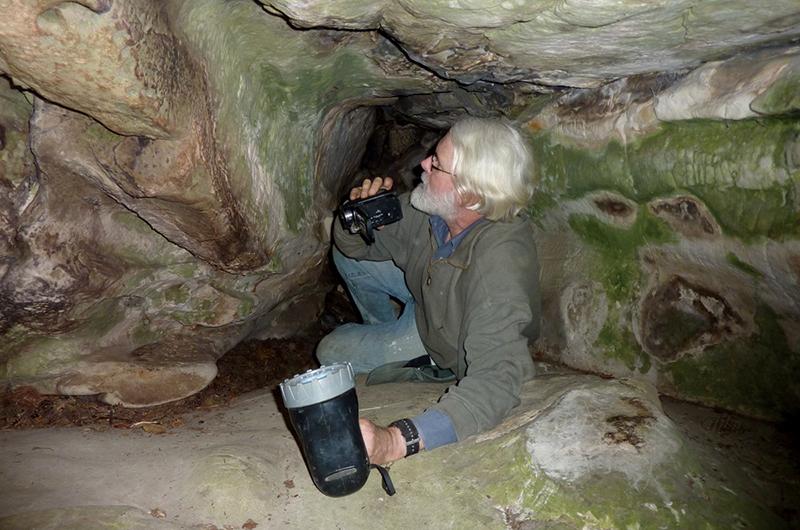

Like so many others on the Vineyard, he’s an example of someone whose passion and knowledge extend well beyond our shores – and return to benefit the Island. Duncan, who lives in Paris when he’s not on-Island, donates a guided tour of hidden French caves containing prehistoric art to the Martha’s Vineyard Community Services Possible Dreams Auction each summer. He also lectures on-Island.

On August 8 at the Aquinnah Public Library, he plans to explore how human immune systems may have adapted in response to pathogens found in early baby slings made of ungulate hides. On August 20 at the Vineyard Haven Public Library, he will discuss the prehistoric Native American Adena tablets from central Ohio. “My hope is to leave the audience reeling: both from the meaning hidden in the warps, and the grandeur of a culture that independently domesticated crops and set the ideological template for the American heartland until the catastrophic arrival of people from the eastern hemisphere,” he explains. A concert on-Island may also be in the works.

Growing up with a CIA-agent father, Duncan spent his youth in places such as Egypt, Vietnam, Lebanon, Cyprus, and Syria. “I thought he was a diplomat, of course, as I was growing up, but these countries were always teetering on the verge of war.” His mother brought him as a young child to the pyramids at Giza, where he learned to search for tiny burial beads in the sand.

His parents also brought him to the Vineyard. He attended many different schools throughout his youth, including in Chilmark. “I sat in the dunce’s chair at the Chilmark School; it’s right where the police chief’s chair is now,” he jokes. “It was a wonderful way to grow up, actually.” He credits his parents for making him “a serial lover of places.” After studying at Yale University, he left for Paris in 1975 “with one extremely strong link” to the United States: Martha’s Vineyard.

As an English teacher in Paris, he met his wife, Nancy, who teaches intercultural and negotiation skills. Duncan continued his travels and research into prehistoric art. “I spend almost all of my time doing research, at my desk or in library archives, or searching for prehistoric art caves.”

He looks at “anomalous clusters of artifacts” and tries to piece together meanings and symbolism, making connections between time and place, and trying to fit each piece into a larger puzzle. For example, finding similarities in ancient art forms from the Nile Delta and the Algeria/Morocco border, he hypothesizes about how and when these cultures intersected, considering that the almost impregnable Sahara desert lies between.

“It’s not a special skill set,” he says of his work unraveling the secrets of prehistory. “It’s problem solving....It’s just going through to the end with optimism.”

Duncan’s work is largely self-financed “on a shoestring” through funds earned by the couple’s teaching. “You’re trying to keep together so many strings, you forget to go down to eat, never mind write a grant proposal. When you’re faced with trying to solve a rich and complex problem,” he says, “I forgot to learn how to write grants.”

Though he’s spent decades exploring places far-flung, he’s also passionate about the history and archeology of the Island. “The graveyard [in Chilmark] is filled with my family,” he says. But don’t expect him to concentrate on one thing: “I’m gravitating towards six things at once,” he says with a smile. “I feel like I’m so far behind schedule, about twenty years.”