On a blue-sky afternoon in August 2009, Marine One thwack-thwacked over Inkwell Beach, delivering America’s First Family to its inaugural presidential vacation on Martha’s Vineyard. Porch potatoes rose from rockers. Beach potatoes waved themselves silly. Cameras clicked. Texters texted. And in the nearby Highlands of East Chop, a red-and-white Victorian cottage with gingerbread detailing stood as a dignified witness. If a cottage could salute, Shearer Cottage surely would have done so.

The media blather carried on for more than a week, not only about the Obamas and their rental digs, golf games, takeout orders, and what-have-you, but also about a conspicuous back story: Hey, there’s a critical mass of other African Americans vacationing here too. And hey, they’ve been doing this for more than a century. The media asked: Why?

Answers: Beaches, tranquility, seafood. Duh. But let us not underestimate the role of a number of pioneers. Shearer is arguably the foremost name among them.

In 1912, Charles and Henrietta Shearer built a twelve-room summer cottage as an inn catering to the Vineyard’s emerging market of African American vacationers, who at the time weren’t welcome to lodge just anywhere. A century later, Shearer Cottage caters to guests of myriad ethnicity and is one of the oldest inns still in operation on Martha’s Vineyard. And what a run it has been, from a heyday spiced with visitations by the well-heeled and famous to today’s unpretentious ambience that remains steadfast to its convivial roots.

It is little wonder that, in 1997, Shearer Cottage was the first landmark to be designated on the newly conceived African American Heritage Trail of Martha’s Vineyard. More recently, the Smithsonian borrowed the inn’s guest book and other artifacts for a future exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Shearer Cottage remains owned and operated by the fourth-through-sixth generations of Shearers. Indeed, its legacy has far less to do with bricks and mortar – make that shingles and porch posts – than it does with people: the dynasty that keeps the inn going; the guests who’ve basked in its hospitality; and a singular segment of the Vineyard summer community that Shearer Cottage helped spawn.

Establishing roots

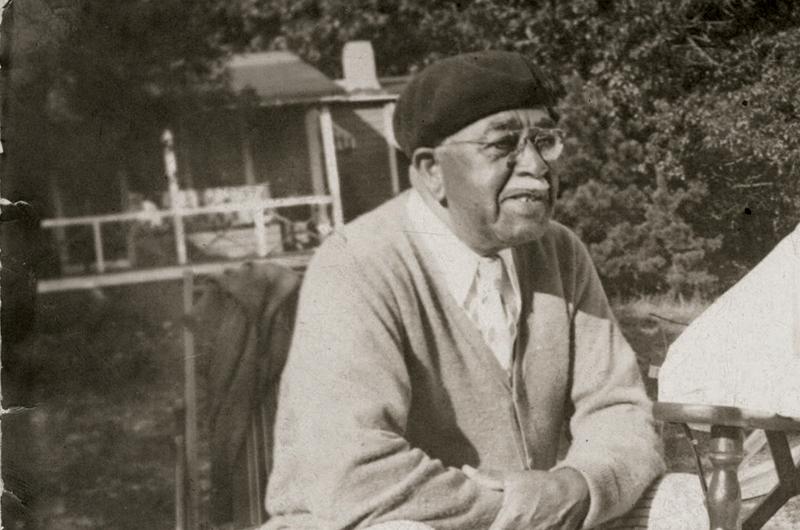

Family patriarch Charles Shearer already knew a thing or two about the hospitality business before he opened the doors of his private cottage to the public. The seasoned hotel maitre d’ was known as a man of distinguished bearing.

“He was sooo handsome,” recalled Doris Jackson Pope, owner and operator of Shearer Cottage, in an interview at the Oak Bluffs home of her daughter, Lee Jackson Van Allen, in January. Doris would turn ninety-seven in February and pass away in April, closing a chapter in the history of the Shearers and their inn. But on this occasion, she swooned like a young girl as she spoke of her six-foot-two grandfather, who summered on the Vineyard in tailored suits, starched shirts, and Panama hats. Never was he seen in a bathing suit. “Someone got him to take off his jacket once,” Doris recalled.

Like many a Vineyard vacationer, Charles hailed from the Boston area. This fact hardly does his story justice, however. Born into slavery in Appomattox, Virginia, in 1854, Charles was a young boy when Union soldiers advanced on the Shearer plantation late in the Civil War. As his father, Master Shearer, prepared a fast retreat, Charles declared he was going to join the Union Army. For this indiscretion, he was beaten, chained in the barn, and accidentally or purposely left behind. Union soldiers ultimately rescued Charles, who later went on to matriculate at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), a Virginia school for blacks and Native Americans. It was at Hampton that he met Henrietta Merchant, a fellow student and free-born woman of black, Blackfoot Indian, and white heritage. They would become husband and wife as well as educators, first at Hampton and later in the public schools of Lynchburg.

In the early 1890s, the Shearers migrated north with their children to Everett, Massachusetts. Perhaps it was Charles’s fair complexion and blue eyes that eased him over the color barrier and into a high-visibility career as a headwaiter, first at Boston’s eminent Young’s Hotel and then at the ultra-eminent Parker House.

Charles was an ardent Baptist and a member of Boston’s Tremont Temple, founded in the 1830s as the first racially integrated church in the United States. A church friend told him about the Baptist Temple, which held religious revivals in the summertime. It was an open-air church. It was in a place called Cottage City (now Oak Bluffs). It was on an island. Perhaps this friend also mentioned the coastal breezes that fan the Island in summer, when Bostonians tend to bake right along with their beans.

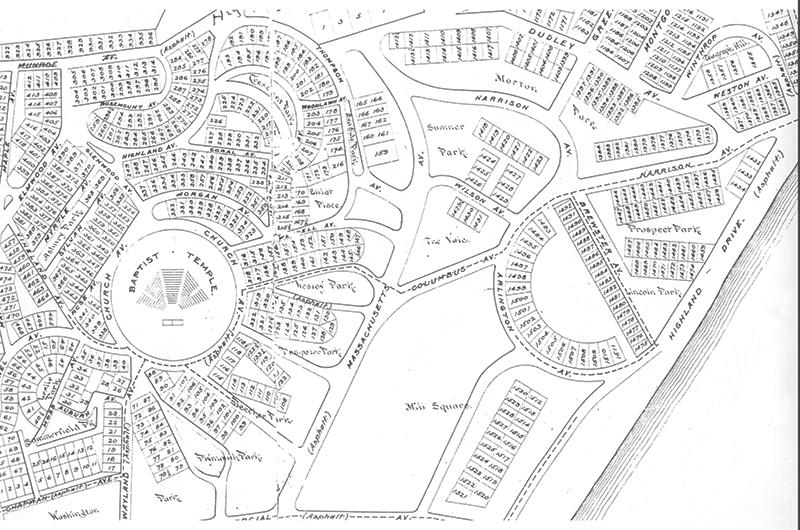

Like many Vineyard visitors, the Shearers were quick converts. They made their first visit in 1895. Before the century turned, they bought their first Island home, sold by a Mrs. Turner, who had boarded the family on prior visits. The cottage was located conveniently near Baptist Temple Park in the Highlands of East Chop. Cottage City was the only Vineyard town where African Americans were allowed to buy property – provided that property owners were willing to sell it to them. The nearby Methodist Camp Ground was a notable exception, with its restrictive racial covenants, and according to Island real estate broker Michael Davin, some East Chop properties have archaic deeds to this day, limiting transfers to “whites of the Protestant faith.”

On the 28th of August 1903, the Shearers bought what would become their keeper home – a larger parcel that faced the park directly. It sat on a bluff with a view of Lake Anthony, now Oak Bluffs harbor, and Nantucket Sound beyond. Island historians refer to the cottage as part of an original colony of about twelve black-owned summer homesteads in the Highlands, some predating the Shearers’ arrival. Year after year, the Shearers closed their home in Everett from mid-June to mid-September to spend whole summers here.

But three-month vacations hardly come free, especially for a family of five. Enterprising Henrietta added an open-air “long house” to the cottage and started a seasonal laundry. Skilled at fluting the fancy petticoats of the day, she quickly became the go-to laundress among well-heeled white summer people. Over time, the laundry grew to employ as many as eight women. A horse and buggy expedited pickups and deliveries.

Each summer, the Shearers invited friends from the mainland to enjoy bed and board in their offshore paradise. The inevitable happened: Friends wanted to come and stay time and again. The Shearers were hard-pressed to steer people of color to alternate lodgings. Black-owned boarding houses in Cottage City were few and small: Louisa Izett and her sister Georgia O’Brien owned guest cottages on upper Circuit Avenue. Mrs. Anthony Smith ran one guest house on upper Circuit and another nearby on Pocasset Avenue. Dora Hemmings’s boarding house on Wayland Avenue in the Highlands was conveniently close to the Shearers, but Mrs. Hemmings, African American herself, reportedly didn’t cater to guests of color.

Opening an inn

The Shearers established Shearer Cottage as a full-blown enterprise catering to paying African American patrons in 1912. The hosts introduced their guests to languid seaside afternoons at East Chop Beach. On Sundays, Charles led them across the road to church at the Baptist Temple, a huge structure with a brick floor and benches, styled not unlike the Tabernacle in the Methodist Camp Ground. Church was often followed by an excursion to Gay Head (now Aquinnah) to visit with friends Henrietta had cultivated among the Wampanoags.

Henrietta passed away in 1917, and thus did the laundry business. Yet the young inn lived on. How could it not? Shearer Cottage and Oak Bluffs, as Cottage City had been redubbed and incorporated, had swiftly become vacation destinations of choice for African Americans of leisure time and means.

Charles continued to ply his labor of love as genteel host, with daughters Sadie Lee and Lily on hand to help run things. They took the business up a notch, retrofitting the Shearer laundry into additional guest rooms, with fresh, white, tie-back curtains. They added an L-shaped porch and upper balcony to the main house. Lily’s husband, Lincoln Pope, being a tennis buff, had a court built in the yard. A proper kitchen and dining room were installed in the house, for like many an inn that preceded latter-day bed-and-breakfast lodgings, Shearer Cottage didn’t limit sustenance to morning java and muffins. Three hearty meals were served seven days a week. It was an era when the guests dressed up for dinner, lingering and chatting well into the evening with their gracious host. Only afterward would the family sit down to eat. The weekly rate for room and board was eighteen dollars. The Shearers didn’t mince on hospitality. The horse and buggy that once delivered petticoats met guests at the wharf.

Leaving their working husbands behind in Boston each summer, Sadie and Lily took the train down to Woods Hole and a boat across the waters, kids in tow, to spend whole seasons working at the inn.

“We were all practically born here,” said Doris in an interview for Finding Martha’s Vineyard by Jill Nelson. “If you were born in February, you were here in April or May. We were brought up here.” She recalled three generations of family cozily occupying the top floor. Today, it’s the “Penthouse,” a two-bedroom guest suite with balcony.

Lily would die a young woman, just three years after her mother, leaving behind her husband and three children, including five-year-old Doris. She also left behind big sister Sadie to run the inn without her.

Developing a clientele

The guests of those early years were business owners, educators, politicians, professionals in law and medicine, and leading lights in the arts. They hailed from Boston, in the main, as well as from New Bedford, Springfield, Providence, and even New York. Some guest names beg to be dropped: William H. Lewis was the first US Assistant Attorney General, during the Taft Administration. Henry Robbins was the Boston court stenographer for the infamous Sacco-and-Vanzetti trial. Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller was the nation’s first black psychiatrist; his wife, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, was an accomplished sculptor. Attorney James W. Pope was the second African American to serve on the Boston City Council. Many guests ultimately bought summer cottages of their own, in and beyond the Highlands. Whenever the inn was fully booked, the Shearers beseeched neighboring friends to accommodate overflow guests in their homes.

It didn’t take long for the Vineyard’s siren song to reach the New York set. Doris attributed the New York connection to her grandmother’s niece, “Aunt” Lucy Belle. “She was a political activist down there,” said Doris. “She was the one who invited up people like Paul Robeson and the Powells.” The Adam Clayton Powells, that is. Adam Jr., the future congressman, was twelve years old when he first lodged at Shearer Cottage with his family in 1921. In 1933, Shearer Cottage hosted his honeymoon with his first wife, Isabel. The couple bought a Highlands home of their own three years later. Other New York guests of distinction included James S. Watson, one of the state’s first black judges; Bishop “Sweet Daddy” Grace; actress-singer Ethel Waters; beauty magnate Madam C.J. Walker; opera soloist Lillian Evanti; and singer Roland B. Hayes.

Fast-forwarding to the 1970s, Lionel Richie and the Commodores stayed at Shearer Cottage on several occasions. Their manager was a Shearer grandson. During their stay, the fledgling recording group honed their act in Island clubs and even once on South Beach.

Many Bostonians who summered on the Vineyard found New Yorkers to be birds of a different feather. “Bostonians were more reserved, and the New Yorkers were more outgoing,” said Doris, with her Bostonian reserve. In a 1983 interview with the Martha’s Vineyard Historical Society (now the Martha’s Vineyard Museum), Highlands resident and Harlem Renaissance author Dorothy West made the point more playfully:

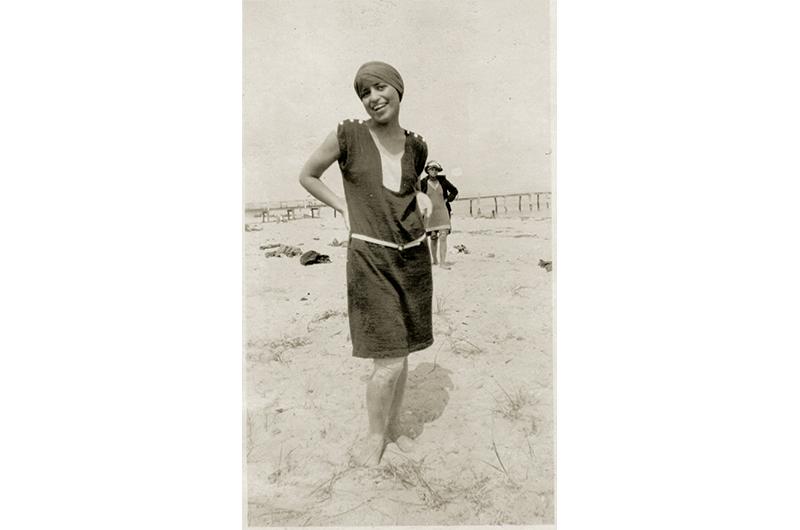

“Now, half these things I say are just for general fun, but when Bostonians went to sit on the beach, we behaved well. We sat quietly on the beach. Then the New Yorkers came. The New York women were good-looking women in good-looking clothes...but they had paint on their faces. People used to say only sporting women wore paint. And the women smoked cigarettes. Even worse than that, they wanted to stay on the beach all day, so they brought food in baskets – and mostly chicken. You see, we [blacks] had a reputation for eating chicken and watermelon. The Bostonians said, ‘They’re going to lose the beach for us! They’re going to lose the beach!’ And I swear to God: One summer we came down, and the beach [sign] said ‘Private.’”

After the members-only East Chop Beach Club was formed in 1931, African Americans of the Highlands, be they residents or guests, had to trek farther afield, south of the Oak Bluffs wharf and Ocean Park, to find welcoming sands at what came to be known as Inkwell Beach.

“That’s where black people wanted to be,” said Doris, noting that neither she nor her children were raised among African Americans off-Island. “It was refreshing to be around other African Americans on the Vineyard. It was self-imposed. We wanted to be together. I think that still holds true today.” The slights of the old days notwithstanding, Doris experienced Martha’s Vineyard as more of an accepting place than not.

A family business

After Charles passed away in 1934, Sadie reigned supreme over the inn. By then, the extended family owned and occupied several homes about the Highlands. The youngest members of the clan whiled away their vacations at the beach and the Flying Horses carousel with their buddies, and charmed guests at the family-owned inn on the bluff. They knew the regular guests as “aunt” and “uncle.”

“It was like a family reunion every summer, without planning one,” Lee recalls of her childhood vacations in the 1940s and 1950s. She stayed in her aunt’s Highlands home whenever her mother, Doris, had to stay on at her job in Boston.

In preparation for Sunday dinners, Sadie would pile the kids into an open car and head to the turkey farm to select the sacrificial fowl, and then return home to pluck, cook, and serve them to upwards of sixty diners. Meals at Shearer Cottage were legendary. Island farmers delivered fresh foodstuffs by horse and buggy to the inn on the little bluff. Sadie, her husband, Benjamin Ashburn, and uncle Robert Merchant commandeered the kitchen and turned out a mix of New England and southern fare: Huge turkeys and legs of lamb. Boston baked beans. Swordfish on Fridays. Sadie’s celebrated rolls. Cottage pudding, homemade peach ice cream, and pound cake. Codfish cakes for breakfast. A hired handyman could hardly refuse a slice of Sadie’s lemon pie in the kitchen after he finished his task.

Once children, nieces, nephews, or cousins of the clan reached their mid-teens, Sadie handed them aprons or mops as soon as they stepped off the ferry each summer. Whether they were changing bed sheets or stabbing at stubborn cubes in the ice trays, they did not complain. Not much, anyway. They were of Shearer blood. Working one or more summer vacations at the family inn is what Shearers do, generation after generation. And for the earlier generations, it was difficult for young blacks to find summer work elsewhere on-Island.

“We goofed off plenty,” confessed Doris, recalling the chambermaid days of her youth. “We weren’t the best workers in the world, but everyone liked us.” A guest named Herbert Jackson liked Doris so much, he later married her.

When their eldest daughter, Gail, came of age in the 1950s, she got harnessed into waitressing. Her friend Olive Tomlinson got harnessed along with her. “We were called ‘the kids,’” says Olive. “We didn’t have a lick of sense.” They were too innocent to know how to handle the forward remarks of a certain cab driver who often picked up and delivered guests, but they weren’t too innocent to hide extra desserts in the china closet for themselves. The era of celebrity guests was largely bygone, but Olive would overhear the grown-ups chatter with anticipation about the impending return of Judge or Doctor So-and-So. Big, beautiful cars graced the parking lot. “New cars every year.”

Olive spent summers at the Wayland Avenue home of her godmother, Miriam Walker, Sadie’s daughter. Olive would always bring home table scraps from the inn to give to King, the German shepherd belonging to the old man who lived next door. He was known as “the professor.” “After a while, the Shearer Cottage people told me the professor was probably eating that food himself. It was disheartening, but I kept on doing it. I never did see him outside his house. The following summer, he was gone.”

Gail’s little sister Lee worked her teen summers in the kitchen, behind the scenes. “I never wanted to wait tables,” she says. “I was afraid I’d spill something.” Her three children, now in their forties, took their own teenage turns working the inn. “They would bank part of their money and spend part of their money. They tell me that’s how they learned fiscal responsibility.”

“What teenager wants to work summers? Hello?” says their cousin Joanne Walker with a grin. The girl from New York worked at the inn as a chambermaid in the 1960s. “You know how it is, working for family. Grandma knew where everyone was. But it was in the natural grain of things. And at least we were working with people we knew. We just got a little weekly salary, but it was enough pocket change to go to the movies or Giordano’s. And after a morning of chambermaiding, you were done. You could do your thing.” Joanne married an Island guy, John Araujo. Two very large family clans gathered in June of 1972 for their wedding reception on the lawn of Shearer Cottage.

Doris’s sister Elizabeth White toiled, after a fashion, as a self-appointed entertainment director. Immersed during the off-season in the New York theater scene, vivacious Liz created the Shearer Summer Theatre on the Vineyard in 1944 and directed it for twenty years. In 1950, she bought Twin Cottage, a withering Victorian mansion in the Highlands, and turned its façade of elaborate porches and balconies into an open-air stage. Upwards of two hundred patrons from across the Island would sit under the pine trees and stars to behold lavish productions such as Shakespeare’s Othello and West Side Story. Actors ranged from professionals like Yaphet Kotto to amateur recruits like Liz’s young nephews.

Tireless, Liz hosted a series of square dances at Shearer Cottage in the 1950s with an ad hoc group of friends. They charged a dollar a head and donated the proceeds to Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. The fundraisers inspired the formation of a club dedicated to supporting Island causes: The Cottagers Inc. is still a thriving charitable organization.

A new day

Liz and Doris stepped into pretty big shoes when they took over management of the inn. Sadie had co-managed or wholly managed Shearer Cottage for nearly sixty years before passing away in 1979 and the mantle went to yet another generation. Liz was now in charge.

“We had no idea of ever selling that place,” said Doris. “Maybe once, and then Liz and I said, ‘We’ll take it over. We’re not going to have this sold. Our grandparents worked too hard.’”

Still, the new captains recognized it was a new day. The inn’s traditional client base could lodge and eat anywhere on-Island they pleased. People vacationed for a week or two, not a month or two. And most vacationers were no longer content with tiny bedrooms and shared baths.

The inn closed for about three years, to be rethought and retrofitted. The twelve small guest rooms became six roomy studios, with en suite baths and kitchenettes. Now that meal service was a thing of the past, the large dining room became a family room. Yet the lively red-and-white exterior and old-school rustic charm remained uncompromised.

After Liz died in 1993, Doris took up the reins as operator. Though she was nearing eighty years old, she did whatever needed doing to keep the inn going: “gardening, painting, getting up on the roof and sweeping it,” she said in a 1996 interview. “You name it, I’ve done it.” Enter the fourth generation of leadership: Lee relocated to the Vineyard year-round and partnered with her mother to keep the inn going. Her brother, David, rounded out the family team.

What changes a century has wrought: The Baptist Temple burned down in the 1940s. Its park grew into dense woodland. The view of the harbor and Sound is so obscured, it defies belief that it ever existed. Twin Cottage, home of the Shearer Summer Theatre, was torn down in 2003, to the dismay of historic preservationists. The geographic center of the African American summer community shifted from the Highlands to the Copeland District near the Inkwell, and its members are sprinkled widely across the Island.

Today’s Shearer Cottage attracts guests from across racial and international lines and serves as a popular venue for private events – especially when the occasions hold resonance for black history or culture. Since 2007, the lawn has set the stage for Elderhostel’s annual “Taste of Road Scholar” lecture series, drawing hundreds of Vineyard visitors and residents to hear prominent speakers such as former Virginia Governor L. Douglas Wilder and former United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young. Even if this icon on the bluff ceases operation as an inn some day, the next generation intends to keep it in the family. “That’s what they say,” says Lee.

Lee carries on with a tinge of sadness this year, now that Doris is gone. She allows that the business today is a struggle. “But I’m happy,” says Lee, “as long as we can pay the expenses.” She profits in the intrinsic rewards: honoring what Charles and Henrietta Shearer created and instilling the work ethic in her grandchildren, the sixth generation – summer chambermaid Camille, age seventeen; lawn mower Kendall, age thirteen; and custodian of flower boxes Kennedi, age ten. She savors enduring relationships that began in and around the inn decades ago. Indeed, Lee met her husband, David, at Shearer Cottage. Her mother, grandmother, aunt, uncle, cousin, and son met their spouses by way of Shearer Cottage too.

“Mom is the one who made sure we held onto Shearer Cottage,” says Lee. “If we lose it, it’ll be over my dead body. She inspired me, just as I’ve inspired my own kids.”

Sources include the archives of the Vineyard Gazette, the indispensable published works of Adelaide Cromwell, Thomas Dresser, Robert C. Hayden, the late Jacquie L. Holland, Linsey Lee, Jill Nelson, the late Arthur Railton, Elaine Cawley Weintraub, and the Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s Dukes County Intelligencer and Oral History Center.