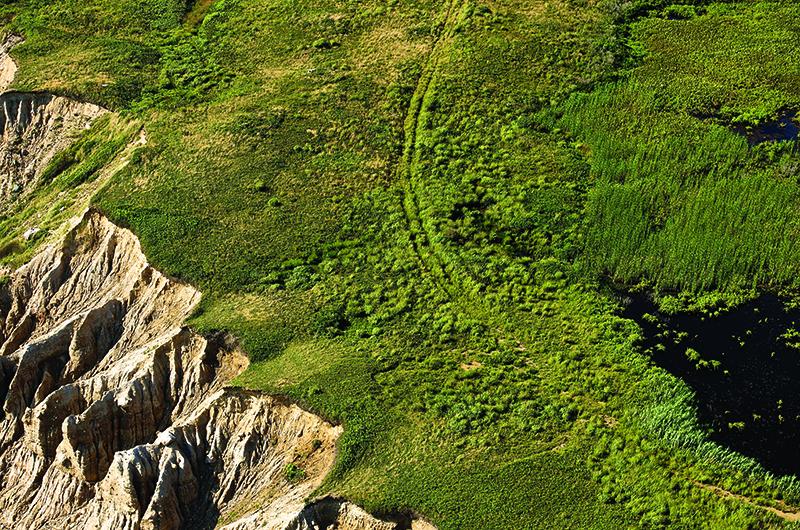

- Aerial photo of Noman's Island.

- Neal Rantoul

First, stay away from Noman’s Land. If not for the strict government injunction against trespassing, then for the threat of obliteration by a five-hundred-pound bomb. After all, it’s not called Noman’s Land for nothing. Yet once upon a time this forbidden outpost was known as the “Isle of Romance,” boasting a bizarre and enigmatic human history replete with tales of Vikings, ghostly visitations, a furtive Nazi landing, and savage rumrunners.

To most Vineyarders, the 628-acre rock is a half-remembered mirage on the horizon, off-limits for so long that little remains in living memory of its tortured human past. The Navy tried its best to exorcise the island of its restive spirits, acquiring it in 1938 to be a bombing range and using it as such until as recently as 1996 (supposedly switching to dummy bombs after 1952). In doing so, they destroyed the vestiges of centuries of tenacious human inhabitation before relinquishing ownership in 1998 and fully turning it over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a refuge for migratory birds.

Last September, the service’s refuge planner Carl Melberg and his team completed a conservation plan that would have the island remain off-limits for fifteen years except for periodic wildlife management. He is also pushing for a full federal wilderness designation, a move that would require an act of Congress and protect the island in perpetuity from any development whatsoever, scaling back even his own team’s modest management of the place. “We want to preserve that sense of wildness out here,” Carl says. “That sense of truly being alone.”

For now, Carl and a crew of biologists, land surveyors, and the occasional ordnance removal expert make a handful of trips to the island every year. The last regular residents moved out when the fighter jets moved in at the onset of World War II.

In 1966 the Navy arranged for a visit by one of those residents, Bertrand T. Wood, the island’s most prolific chronicler and author of the 1978 book Noman’s Land Island: History and Legends. He had lived on Noman’s Land from 1924 to 1933 when his father was the caretaker. The trip back was a devastating experience for Wood. He’d expected to revisit the old icehouse, the bait shack, the west barn, the store, Uncle Cameron’s house, the shop, Crane’s bungalow, the east barn, and his childhood home. He found instead a landscape razed, overgrown, and unloved.

“I don’t understand how they could have vanished without a trace,” he was quoted in a Vineyard Gazette article at the time. “An Island of Desolation, I call it. Let the terns have it.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service is now making good on his suggestion. Free from mammalian predators and poised squarely in the Gulf Stream, the island is an important off-ramp on the Atlantic Flyway, the East Coast’s primary bird migration route. Nearly half of the island is wetlands habitat, with two large ponds and a number of smaller ones supporting a variety of flora and fauna. The birds that stop over at Noman’s have something of a proprietary attitude about the place (and a fearlessness around humans that can be a little intimidating).

Approaching the island’s northern shore, with Squibnocket three miles in the wake, brings a visitor upon an indifferent and incontinent cocktail party of cormorants preening amid the scat-spattered pebbles, no-trespassing signs, and the random rusted rocket casing. The peninsula called Cobble Spit, when viewed from above, sensibly points back toward Martha’s Vineyard.

Approaching Noman’s Land from the south, in the route of the screaming A-10s that ventured from as far as New Jersey to blast the place to smithereens in the years following World War II, feels like courting disaster. Warnings on nautical maps roughly approximate the path of those warplanes’ approach to help avoid the unpleasant discovery of live weapons by anchoring pleasure craft, as if the sheer face of Noman’s southern cliffs was not formidable enough.

On shore and especially inland, the landscape of Noman’s can appear monotonous, an undifferentiated and impenetrable mass of swaying shrubs. But botanists would tell you otherwise, pointing to the unusual variety of plant communities such as cranberry swale and cattail marsh.

Despite its sense of desolation, the place also feels aggressively alive. Seals casually waddle ashore where mats of decaying organic matter lend a pungent funk to the wrack line. Inhabiting its hundred-plus acres of freshwater ponds and marshland are innumerable spotted turtles (one of the largest populations in New England), along with the odd snapping turtle that emerges from the murk occasionally to eviscerate a gull corpse among a backdrop of spent shell casings.

The early years

If Noman’s is all but abandoned by the powers that be, it won’t be the first time. Ten thousand years ago, it was not an island at all, but a craggy heap in the center of a vast coastal plain, orphaned by the Laurentide ice sheet as it made its lethargic retreat to the Arctic. With sea levels at that time more than four hundred feet lower than today, the shoreline was hundreds of miles away. Over the millennia, as the waters rushed in, even the Wampanoag giant Moshup seemed to want none of the place: Legend says he drew his big toe between it and Martha’s Vineyard, flooding the land in between (the land division between the two islands happened about a thousand years ago, according to geologists). Other than a few projectile points, a mortar and pestle, midden piles, and bits of pottery – some perhaps as much as five thousand years old – Native American habitation left little impact on the land.

Facts are equally hazy about the island’s early European history. It was first sighted by the English explorer Bartholomew Gosnold in 1602, or maybe it wasn’t. Europeans originally named the island after the Wampanoag Sachem Tequenoman in 1666, or maybe they didn’t. Perhaps it’s named for a town, Nomansland, twenty miles south of Chilmark, England. Or it could be just what it sounds like, no man’s land. There is even the claim, vigorously defended in some circles, of the existence of a pre-Columbian Norse colony that would have predated Gosnold’s visit by some five hundred years. Hopes for that theory’s vindication were buoyed by the discovery of a runic rock half-submerged near the low tide line, bearing the name of Leif Eriksson. It was later revealed by Norse scholars to be a hoax, and a New England fisherman claimed to have carved it in 1913. In any event, we know for certain that in 1715, Jacob Norton and his family moved to the island, and Noman’s myths began to be exported to the mainland along with its prized mutton.

Much of this early period of Noman’s is shrouded in a haze of romance and ghost stories, including at least one apocryphal tale of buried pirate treasure. An influx of seasonal fishermen and their families were said to be driven mad by “sweet solemn music” emanating from island houses, and one particularly noisome spirit – rattling silverware and slamming doors – allegedly spooked many fishermen into an early exit from the island’s lone boarding house.

The European settlers made quick work of the island’s trees, denuding the oak and cedar forests and replacing them with sheep that – so the story goes – were deaf from the constant roar of wind off the ocean, and whose fleece and mutton would fetch the highest prices at auction in Boston and New Bedford. Noman’s Land farmers claimed the animals acquired their lustrous sheen and delicate taste from the seaweed they consumed on their daily meanders along the shore. Farming attracted more farming, and by 1750 the Luce family had joined the twenty Nortons already living full time on-island, together raising more than eight hundred sheep. In the summer through the fall, some sixty cod-fishing families would pass through, and two villages (Gull Town and Jimmy Town), a boarding house, church, and store sprung up to serve the burgeoning colony.

As cod fishing became less profitable in the late 1800s, the vitality of the island slowly bled away, leaving the many fishing shacks to be blasted into disrepair by the salt spray and winds. By the end of the century only one family, the Butlers, remained as year-round residents. In 1896 The Boston Globe sent a reporter to visit the castaway family, finding a resourceful if odd bunch.

Their daughter, it seemed, had been possessed by the spirit of a Boston milliner and was given to frenzies of hat trimming. Mr. Butler himself revealed his family’s isolation in his own idiom. “We don’t git any news here at this time of year ’ceptin’ what comes on the wind, and it’s about two months now since we’ve heard from the American Continent,” he told the newspaperman. “Are we fighting England over the Venezuela affair?”

It was a sentiment so humorously quaint even in 1896 as to merit publication. As for the daughter, she was neither the first nor the last loco local. Perhaps it goes with the territory.

To view Martha’s Vineyard from Noman’s Land is to undergo an unsettling cultural vertigo. The structures of Aquinnah seen faintly through the haze might as well be Manhattan, while the very idea of the mainland itself remains abstract. This overwhelming solitude has inspired awe in some and outright psychosis in others.

“The wind howled and the waves pounded and sometimes it seemed that all the lost souls in Hades were on that small piece of earth,” wrote the wife of a former caretaker in the Vineyard Gazette in 1951. One such lost soul was Frank Crapo, who put the island on the front page of The Boston Globe in 1931 when he went “violently insane” and terrorized the Wood family, the caretakers for the Dedham patrician Joshua Crane, who had bought up the island in 1914 for use as a hunting and fishing playground. Crapo stalked the Woods over four interminable days, claiming to be pursued by an imaginary chap named Walter. “It took nine of us to hold him down as Crapo had the strength of insanity,” wrote Bertrand Wood, after the family finally captured him for delivery by the Coast Guard to the Taunton Insane Hospital.

An influx of rumrunners

With the onset of Prohibition in 1920, the Wood family was subject to many adventures, as the Atlantic Flyway gained a new reputation as the Atlantic Boozeway. Ships from Canada and beyond would rendezvous in international waters three miles off the coast, flooding the mainland black market and the beaches of Noman’s with a torrent of hooch.

“They were not hardened criminals as most people thought,” one Noman’s resident at the time reflected years later in the Gazette, “but very polite and kind-hearted and were always a welcome sight for us on Noman’s Land.”

One of those rumrunners was the late Craig Kingsbury, a Tisbury selectman and the model for the cantankerous Quint character in Jaws. In Craig Kingsbury Talkin’, the book published by his daughter, Kristen Kingsbury Henshaw, he describes one of the more lively episodes off Noman’s when one of his rumrunning captains raided a collection of antique whaling gear rusting in New Bedford for use in fending off hijackers. Of particular interest was a harpoon with an exploding head designed to penetrate and destroy the interior of a whale’s head – or, in this case, a boat.

“He mounted the gun on the stern of his schooner, covered it with a tarp, and had it set to go in case it was needed,” Kingsbury recounts. “The hijackers used to lay back of Noman’s Land in these speed boats and come out and hijack a schooner trying to make it with a load of hooch. I guess they had clipped two or three and came after our lads. Our captain spotted ‘Charlie the Chink’ [a notorious hijacker] and his merry men seventy-five feet off his stern. He warned them but they kept coming, so off with the tarp, and let her go, right square into the bow and right through the gas tank. ‘There’s a sound like a clap of thunder and Mother of God! It blowed them foolish bastards farty-seven feet into the air and it rained matchsticks and giblets for the next half hour!’ according to my source. I wasn’t on that trip but I did help haul the cargo ashore. After that little caper the rest of those hijackers gave the old captain one hell of a wide berth.”

About the rumrunning trade, Kingsbury is quoted as saying, “A lot of people made a lot of money. And a lot of guys died. I think ‘The Chink’ went for a swim in a concrete bikini in Narragansett Bay.”

Other rumrunning adventures on the waters off Noman’s were less picaresque. One early April morning in 1923, an elegant hundred-foot steam yacht named the Flit was abandoned on the island, its crew having disappeared after a gruesome rendezvous just off of Noman’s with the John Dwight, a steamer out of Newport laden with barrels of Frontenac ale. Everyone on the John Dwight was murdered and nine bodies were later recovered by the Coast Guard. No one from the Flit was ever seen or heard from again.

“All of the bodies were bruised, cut and lacerated,” wrote the Gazette, “and the body of [John Craven of Rutherford, New Jersey, who had allegedly boarded the ship with $100,000 only days before] was so disfigured as to make identification difficult.” The Coast Guard dropped depth charges to destroy the wreck and to discourage salvagers but their mission was not entirely success-ful. “Many barrels of the ale were picked up, however, and enjoyed by [Vineyard] residents,” according to the Gazette.

Bertrand Wood wrote that several bodies of the murdered men from the John Dwight drifted ashore on Noman’s over the following days. He claimed the men were buried in the island’s graveyard – which, along with a network of barely visible stone walls and the ruins of a cellar, is one of the only remaining indications of the island’s human history, including the lone toppled headstone of Titus Luce from 1862 and a grimly suggestive human-sized depression in the ground.

From the war to today

Joshua Crane, the so-called monarch of Noman’s Land, had ambitions for the island grander than a stopover for bootleggers – or Nazi submariners, for that matter. Although World War II experts may be skeptical, Crane’s daughter, Priscilla, claimed that in 1938 she found her larder raided and a German cigarette case on her counter. That same year, the Navy leased the land from Crane for $50,000 and promised to return the island after the war in its original condition.

While he waited, Crane drew up fanciful plans to convert it into a luxury resort for sportsmen featuring an eighteen-hole, 6,850-yard golf course that, with its stunning views of Gay Head, he predicted would “become the most famous and the best course in the world.” The Navy terminated those plans in 1952 when they simply took the island by eminent domain.

Since the transfer to the government, human presence there has been scarce, but one Vineyard civilian has visited more than any other: biologist Gus Ben David, who lives in Edgartown. He was originally sent in 1973 by Vineyard Gazette publisher Henry Beetle Hough to report on the biological diversity of the place and the Navy’s stewardship thereof. He says he has accompanied government officials to the island at least eighty times since.

“One of the most fascinating factors in my life has been my relationship with Noman’s,” Gus says. “It’s unbelievable; it’s being in another world.”

Gus was a hawk when it came to the governance of the island under the military, lauding the Navy’s bombing campaign for its curious preservative effect on wildlife. The counterintuitive argument that blowing up the refuge was a boon to wildlife had obvious limits; a colony of four hundred roseate terns discovered by Massachusetts Audubon staff in 1972 had been reduced to a three-tern crater on a return visit shortly thereafter. But strangely enough, there’s logic to the claim. By prohibiting human habitation, a natural wildlife environment has been created, one that is unmatched elsewhere on the eastern seaboard.

“It’s a biological gem,” says Gus, who is critical of the Navy’s recent attempts to clear the island of unexploded ordnance, fearing it will become more attractive to interlopers. “I wasn’t an advocate of that at all,” he says. “I knew where every single bomb was on that island.”

Like almost anyone who has spent any time on the island, Gus has at least one terrifying story. On an overnight trip, he fashioned a sleeping bag out of an aluminum-lined tarp and climbed into bed with a handful of Canadian Club nips, when, on the otherwise sublime summer’s evening, he observed the unwelcome approach of a vivid, dramatic thunderstorm over New Bedford.

“Well, don’t you know that storm kept getting closer and closer,” he says. “It was a violent thunderstorm that came over that island, I’m telling you, and I was at ground zero in this aluminum bag. An aluminum bag, can you believe that? I’m telling you right now, not many things scare me in nature, but I said, ‘I’ll be damn lucky if I survive.’ This storm lasted for hours and if lightning had hit anywhere even near me, I would have been gone.”

He had separated for the night from his companions on the expedition: marine biologist Greg Skomal, who had slept offshore in a motorboat with a handmade pram in tow, and a pair of federal agents, who camped on the far side of the island. The next morning Gus learned that Greg had endured an equally harrowing night, losing the borrowed boat to the storm. Gus still shakes his head in weary disbelief when recounting the story. “The feds thought I was a dead man,” he says.

Now even the feds want out. With a prospective federal wilderness designation, the island would see even fewer government visits and vastly limited management.

It’s the direction Noman’s has been headed since Joshua Crane was forced to give up his dream of the island as a resort for the wealthy. The Native Americans, Norsemen, pirates, farmers, fishermen, rumrunners, Nazis, and fighter pilots are all gone, and the island lingers indefinitely in a state of beautiful abandon – forgotten, haunted, and yet still full of life. It has seen forests, pastures grazed by hundreds of sheep, ramshackle fishing villages, posh hunting lodges, Quonset huts, and airstrips. Now there’s almost nothing man-made amid the remains of decades of Navy bombing, save a few snake-infested Conex shipping containers in the heart of the island, stocked with replacement signs warning would-be visitors to stay away. To biologists the island is a paradise; the human drama has all but ended. The occasional plastic birthday balloon washes ashore, a missive from an alien civilization. The birds poke curiously at it before returning to their unharassed lives. The lost souls of Noman’s may be finally at rest.