Among the most popular regular features in the magazine are its history stories – no surprise there, when you consider how unique and adventurous the Island’s history is. The story of the Vineyard arcs back to the earliest English settlements in North America, and through the exploits of its mariners – men and women alike – it circles the planet countless times. Today the heritage of everything the Island has been and done lives on more plainly and vibrantly than it does in less naturally bordered and insular places. You glimpse its influence every day on the water, along the coastline, across the landscape, and in the legacies and lives of inhabitants, whose ancestries stretch back one generation – or twenty.

In its coverage of things past, the magazine looks for topics that go way back as well as those that lie within the memory of people living on the Island today. It seeks to reinterpret rather than merely reprint. In doing so, it offers a latter-day perspective on what went before – and sometimes adds useful historical thought to debates that, more so in a Vineyard setting than in many other communities, may be still going on.

Here are excerpts from six features from the past, about the past. A few offer the chance to add brief updates on what we know now that we might not have known when the stories were published. A few others stand on their own.

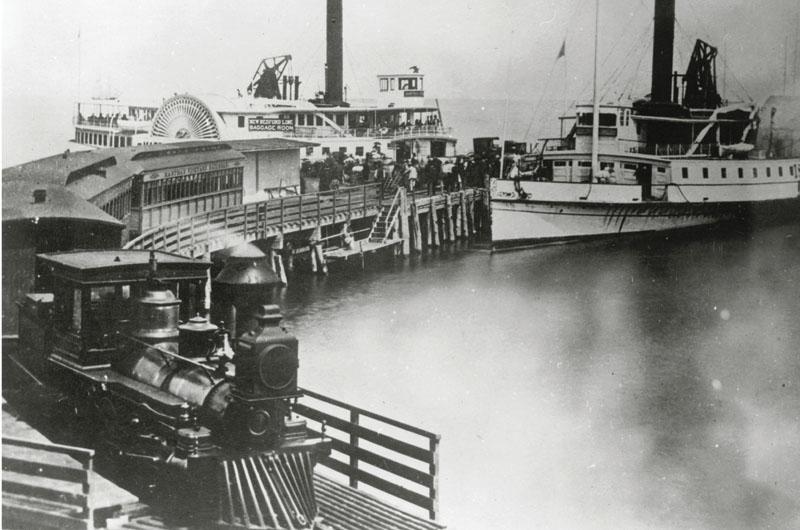

All aboard

From Oak Bluffs to the Atlantic

In the summer of 1874, following a nationwide financial panic, Vineyard entrepreneurs – with the controversial backing of the town of Edgartown – hurriedly built a railroad to connect the famous resort of Cottage City (Oak Bluffs) with Edgartown and with a struggling resort hotel at an otherwise uninhabited and barren Katama. In 1991, the magazine recounted both the disastrously sloppy construction of the new railroad line, built in a hurried eight weeks that summer, and the happy day, late that season, on which the first train ran.

A mainland contractor began to work on one end of a bridge across the inlet to Sengekontacket Pond. Edward R. Dunham of Edgartown began to work on the other side. The gag paid off – when the two ends met in the middle, the elevations missed by two inches. Like good New England builders they went straight back to their plans to prove that the other deserved the blame. Dunham had figured it right. The bridge was somehow jimmied together.

Then came The Little Engine that Absolutely Couldn’t. Fearing that a conventional locomotive might scare horses, and believing somehow that one disguised as a coach would not, the railroad men bought a “dummy.” This was a common passenger car with a steam engine at one end, favored by elevated railroads in the cities. On August 5, 1874, while thousands lined the tracks, the dummy began its maiden run. It got as far as the first curve. There it stopped, for the main problem with a dummy’s direct-sprocket drive was that the steering wheels could not steer. Elevated railroads are straight; Island railroads bend. The message went down the tracks – find another way home.

But if the dummy got no further than the first curve on the first try, her replacement – this time a real locomotive – got no further than Woods Hole harbor, where it sank. The Active was waiting on a flatcar for the trip across the Sound on August 17 when a couple of loaded freight cars broke loose, struck the flatcar, and drove it into a buffer. The flatcar stopped, but the ten-ton locomotive tipped over the edge of the wharf.

Raised somehow from the muddy harbor bottom, the Active was shipped up to Boston, where seaweed was hurriedly picked from her cylinders. The season was nearly done. Finally, on August 22, the Active rolled down a special gangplank from the steamboat Island Home at Mattakeset Lodge in Katama.

“Gaily decorated with flags, the engine started away at a brisk pace and rapidly made the distance toward Edgartown, producing a sensation all along the route,” the Vineyard Gazette said. “And at last we drew up before the ‘Sea View [Hotel],’ the driving wheels ceased to rotate, and ’mid cheering, music from four bands, salutes and greetings of the most cordial description from the crowd, we alighted, and the first trip of a locomotive over the Martha’s Vineyard R.R. had been successfully run.”

Update: What this story missed in 1991 was the fact that the Vineyard was already basically familiar with rail transportation when it launched this otherwise chowder-headed scheme in the summer of 1874. The year before, Island businessmen had established a modest – but also ultimately more successful and longer lived – street trolley system that would, within a few years, thread through much of what is now Oak Bluffs and, at its most expansive, run from there to the Lagoon and Vineyard Haven.

For a lively illustrated story of the trolley system and the Martha’s Vineyard Railroad, look in Island bookstores for Rails Across Martha’s Vineyard, a seventy-two-page book on the subject written by Herman Page of Oak Bluffs (South Platte Press/Brueggenjohann/Reese, 2009).

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Tom Dunlop that ran in Fall–Holiday 1991.

Lightship down

The sinking of the Vineyard Lightship during the Hurricane of 1944 was the last great sea disaster involving loss of life in Island waters. Harold W. Flagg of Sandwich was on shore leave when the vessel foundered, killing all twelve of his shipmates who were manning the vessel. In an exclusive interview with the magazine, Flagg, then eighty years old and the last living member of the lightship crew, shared an unpublished memoir he’d written. In it, he speculated on what it must have been like for his fellow crewmen that September night as the storm pummeled the ship, which had been ordered by the Coast Guard to stay at anchor at the western entrance to Vineyard Sound. It was wartime, and lightships did not leave their posts for any reason.

“Occasionally, the weather would be so rough that all work would be suspended,” Flagg writes in his memoir. “These were times that it was impossible to move about the ship, and the time would be spent in our bunks simply hanging on, trying to keep from being bumped about.” And this was during a regular winter blow. He imagines a vessel turned broadside to waves breaking twenty feet high against her hull and superstructure, and extrapolates from there:

The two diesel generators in the engine room, which supplied electric power, would have quit when water reached them through the scuppers, hawsepipe, ventilators, skylight, or some down-flooding combination of all of them; after that, there would have been no lights or pumps and no hope of ever turning on either one again. The boilers were fed by hand and shovel; it would have been impossible to stoke them in those seas – indeed, it would have been impossible to stand up in those seas – and at some point the water would have drowned the fires and killed the engine. The broad loading doors on both sides of the ship were hinged in three places – up and to the sides – and a report from the first dive on the wreck in 1944 suggests that at least one set of those doors simply caved in to the battering.

It is impossible to know whose ordeal aboard was the worst, but Flagg notes that five of the crew – including his roommate, John Stimac – had only come aboard the vessel a few weeks before. For them, he says, those last few hours must have been particularly fearsome, for the ship was still new to them, and the magnitude of the storm newer still. There was, of course, a plausible final moment while things were still lit, secure, warm, and running when the ship might have let go of her main anchor and tried to put her bow into the sea and head for deeper, flatter water, or even looked for the lee of a shoreline. But the crewmen of the Vineyard Lightship appear to have done everything they could to hold their ground, as ordered, on an empty, outraged sea.

Update: Well into old age, Harold Flagg and his wife, Ethel, continued to host the widows, children, and grandchildren of his lost fellow crewmen at their home in Sandwich. In 1999, he dedicated the U.S. Lightship Memorial at Coast Guard Park on the New Bedford waterfront, where the bell of the lightship, recovered from the wreck, now stands. Ethel Flagg died in the spring of 2004; Harold, who had gone on to serve another thirty-eight years in the Coast Guard after the loss of his ship, died a few weeks later.

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Tom Dunlop that ran in September–October 2003.

Where silence reigns

Roots of american sign language: the deaf voice of the Vineyard

It was a singularly remarkable phenomenon on Martha’s Vineyard: the unusual incidences of hereditary deafness in the up-Island population from the time of colonial settlement through the early part of the twentieth century. The cause, a genetic trait, was exacerbated by the tendency to intermarry before mainlanders began coming to the Vineyard in greater numbers to vacation and live.

There was no other place quite like it. In its solitude, Martha’s Vineyard had fallen victim to a recessive gene for deafness that kept appearing in up-Island families like a pebble in a shell game. Yet solitude was also a blessing. For 250 years it sheltered these rural Vineyarders from the mainland idea that an inability to hear or speak could be a handicap. Self-reliant in all things, they began to build on a system of signs their ancestors had used in England. In the stores, on the farms, and along Menemsha Creek, Martha’s Vineyard sign language was the only language that everybody knew.

It is possible to see the career of Joan Cottle Poole as the final living expression of the Vineyard deaf, the last of whom died in 1952. Joan, thirty-three, is supervisor of education for the deaf at Newton North High School outside of Boston.

Growing up in Chilmark, she learned some old Vineyard signs from her great-grandmother Emily, who could hear. But at age nine, Joan didn’t know how significant these signs were; she thought they might be Indian.

In November 1977, at age nineteen, Joan led a team of Ph.D.’s from the New England Sign Language Society to Martha’s Vineyard, and over two days coaxed three hearing Islanders to recall a language they had not used in fifty years. On rudimentary video equipment, they captured some two hundred Vineyard signs.

The signs Joan saved on those two November afternoons are elegant both in logic and simplicity. At the Chilmark Store, a deaf fisherman (or a hearing one, to keep the news from a stranger at his elbow) would hook both index fingers in the same direction to tell Rex Weeks, the hearing storekeeper, that he had landed a swordfish. These hooks represented the dorsal and tail fins of a swordfish breaking the water. Just as on the mainland, on the Vineyard “boat” was signed with two cupped hands moving from the body as if over waves. But to say “sailboat,” the mainland deaf lifted their thumbs from this gesture to signify a mast, while Vineyarders simply tilted their hands to one side, meaning a boat that heels over.

Between 1825 and 1870, Martha’s Vineyard sent more children and more families to what would become the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, than any other area in the country. The national sign language was still new, still malleable. And into the school charged the Mayhews and Luces, Tiltons and Wests – lively Vineyard youngsters with a language all their own. Joan Poole has a theory about what happened next:

“The rest of the kids wouldn’t have been as fluent as the Vineyard kids. Probably the first Vineyard students were thought to be taking the beautiful [newly imported] French signs and distorting them, just destroying them....The teacher is standing up there signing ‘cat’ his way, and as a Vineyarder you’re going to still sign ‘cat’ your way.” Joan reasons that the national sign language was finally woven together from the French system and from the Vineyard’s. It is a contribution too long overlooked. American Sign Language owes a special debt to a seaside community as unique as it was silent, a place where the word “handicap” had to be spelled out.

Update: The library at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Edgartown now has an extensive collection of materials on the subject of the Island deaf population, including notes from Alexander Graham Bell (the inventor of the telephone was also a teacher of the deaf, who came to the Vineyard to study the occurrences late in the nineteenth century); contemporary newspapers and census records from the period; and a thesis on the subject by Nora Ellen Groce, author of the seminal book on the subject: Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language (Harvard University Press, 1985).

The edited excerpt above is from an article by Tom Dunlop that ran in May–June 1991.

May Day 1964

In an oral history interview, the late Nancy Whiting, a co-founder of the Martha’s Vineyard chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, told this story about a trip she took with four other Island women (Polly Murphy, Peg Lilienthal, Virginia Mazer, and Nancy Smith) to Williamston, North Carolina, to support the struggle of blacks to register to vote.

The registering we did for half a day. It was May Day, and Golden Frinks, one of Martin Luther King’s organization leaders, wanted to do a demonstration outside Sears Roebuck for unfair hiring practices and asked us to join. We knew we were in for it; there’s no way five white women and a bunch of black people were going to protest on May Day outside of Sears Roebuck, without getting arrested. Which is what happened.

I remember as we got out of the police car to go into the jail, there was then a great crowd of white people. And that was my moment of truth about hatred, looking into the eyes of hatred. It was terribly shocking. I realized they would kill us the first chance they got. They absolutely detested us. I’m a middle-class kid. I’d had various personal tragedies in my life, but I’d never seen that before. I never forgot and I never will. I’ve tried to swing around to the other side, thinking what it must be to feel that way, what a terrible thing it is for the hater, but at that moment I hadn’t seen it before, and there it was, just sheer, sheer hatred. You can’t say it was frightening. It was astounding.

I know that when we came back – I was at that time the tax collector in West Tisbury – I thought, “I don’t know if this one’s going to fly.” Of course, I’d been elected, duly elected, but I thought, “Well, there’s such a thing as impeachment.” And the first time I walked into the office, which was then the old police station, after we got back, there was Nelson Bryant, the chief selectman, and Charlie Tucker. “Listen, tell us all about it. What was it like?” They were all excited. I was stunned. We were prepared for the worst. It was a radical thing for us to have done at that time – from here – an apolitical, insular sort of place.

This edited excerpt is from an article by Nancy Whiting, as told to Linsey Lee, that ran in May–June 2003, and was excerpted from Vineyard Voices by Linsey Lee (Martha’s Vineyard Historical Society, 1998), a project of the Oral History Center of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Without a paddle

A seventy-six day strike by officers and crewmen of the Steamship Authority – from April 16 to July 1, 1960, the longest in the boat line’s history – crippled the start of the summer season that year. But it also showed just how resourceful Vineyarders and visitors could be when it came to getting from here to there and back.

A week or so after the strike began, Linda Marinelli of Oak Bluffs got a phone call that would change her life. At the time, she and her husband, Charley, were struggling to make ends meet – he fished, and she ran a fish market at Farm Neck. The phone call came from a man representing a group of Vineyard businessmen who were organizing alternative ways to carry people and cars to and from Woods Hole and Martha’s Vineyard. They had leased a tugboat and a barge to carry the cars and a few trucks at a time.

So Linda agreed to coordinate the operation for loading cars and passengers in Woods Hole, provided that Charley’s fishing boat, a forty footer called the Vera B., was first in line to take passengers. He could carry twenty-one people per trip, which took about an hour each way, and sometimes he worked around the clock. At $3 a head, he was making a steady income – far more in a day than he made fishing. In a 2002 memoir, Never Say Die, Linda refers to the strike as “our first break.”

“I had hundreds of sets of car keys to keep track of, and I never lost one,” says Linda, who loaded a body-bearing coffin onto a boat at low tide and then walked the dog of a driver who had gone over, leaving her car behind. She learned the art of loading autos not only onto the barge but also onto Captain Alfred Vanderhoop’s dragger Papoose, which could manage two or three cars athwart her decks. “We ran them up the planks and packed them on like sardines,” she says, “with one car on either side, and maybe a small Volkswagen on the end.”

Other boats did well too. Stuart Bangs of Vineyard Haven, then working in his family’s market, spent the first half of that summer on Parakeet, his father Paul’s 1927 freight vessel, converted from what Stuart calls a “rich man’s play-boat.” Parakeet brought over passengers day and night, and the first shipment of bread every morning. Stuart says that for the fishermen recruited into the transportation effort, the strike was a boon.

“They were getting steady cash every day,” he says. “A lot of fishermen seemed to have new cars after the strike was over.”

This edited excerpt is from an article by Laura D. Roosevelt that ran in May–June 2005.

Talkin’ about a revolution

When in the winter of 1977 Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Islands learned that redistricting would cost them their separate county representatives in the General Court in Boston, the Islands voted to secede from the commonwealth – and perhaps, if it came to that, the Union.

Massachusetts started to offer little sweeteners, such as toll-free phone calls for Islanders wanting to contact their new off-Island representative. But the issue became increasingly complicated. Should the Vineyard become the fifty-first state, or simply transfer its allegiance to some state other than Massachusetts? Other states began wooing them.

The governor of Connecticut, Ella Grasso, extended a “warm Connecticut welcome” to the Islanders. From its beginning, she said, her state had been a refuge for disgruntled Massachusetts citizens. New Hampshire’s House of Representatives passed by an “overwhelming majority” a resolution inviting the Islands to join “this nation’s most democratic state.” An aide to the governor of Maine was quoted in the papers as saying that state had split in 1820 from Massachusetts out of “a feeling of remoteness” and pointedly noting Maine had one representative for every two thousand people.

Everett Poole, a Chilmark selectman, recalls: “The governor of Vermont sent me a letter with half a gallon of maple syrup and said his state would love to have a sea coast. I sent him back four pints of quahaug chowder.”

John Alley, one of the secession ringleaders from West Tisbury, also was courted by Governor Snelling. “He rang me, when I was running the general store one day. I just thought it was a crank call and I said, ‘Yeah, sure,’ and I hung up. And the guy rang back and said, ‘No, I really am the governor of Vermont.’ Later he came in the store two or three times. I got letters from him saying he would be glad to have Vermont annex Martha’s Vineyard.”

What did it all achieve? The Islands did not get their representatives back. But they did win some acknowledgement of their unique circumstances as well as one aide each assigned to the representative charged with communicating their special needs.

But more than that, they got scads of publicity, which is what a resort community needs. Says John Alley: “The place became far more popular than it already was. In retrospect, if we had another opportunity, I think we’d all do it again.”

This edited excerpt is from an article by Mike Seccombe that ran in September–October 2007.