Chances are good that unless you’re a sailor or boater, you haven’t seen one. Chances are even better that if you have had the good fortune to cross paths with one of the giant leatherbacks that frequent Vineyard waters, you haven’t forgotten it. They are the largest turtles on earth, often growing to more than six feet long and weighing up to 2,000 pounds, with a flipper span that spreads up to twelve feet and a head seemingly the size of a helmeted NFL linebacker. Their black, rubbery carapace is shaped like the bottom part of a heart, lined with vertical ridges, and has been compared to an overturned dinghy, a Volkswagen Beetle, or a golf cart.

Just ask Captain John Potter, who spends lots of time at sea with his charter fishing boat the Skipper out of the Oak Bluffs Harbor. A leatherback sighting never fails to excite his passengers, he said, and most of them have never before had the chance to see a huge sea turtle. “We love seeing those,” he said. “It’s something you don’t see every day.”

But between being out on the Skipper and fishing the Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass & Bluefish Derby with his twelve-year-old son, Zak, Potter is more familiar with leatherbacks than most. “We’ve seen eight in a day out bass fishing,” he said. “When you’re out there fishing the Derby, you see quite a few of them.”

“I’ve had a lot of people tell me the first time they saw one they felt like they were looking at a dinosaur,” said Kara Dodge, a research scientist at New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life and a leading authority on the giants. “They have a very prehistoric, dinosaur-like appearance.”

They look prehistoric because they are. Leatherbacks are the last living representative of a family of turtles, the Dermochelyidae, that traces its roots back more than 100 million years. Leatherbacks have been around since the time of the dinosaurs, surviving mass extinctions and outliving their closest relatives to make it to the modern day.

While there isn’t a lot of evidence about what ancient leatherbacks and their extinct cousins may have eaten, over the eons the modern leatherbacks evolved into jellyfish-eating machines. So even if you haven’t yet seen one of the turtles, if you’ve spent much time on the Island in the late summer and fall you have probably seen – and recoiled from – their dinner. The turtles’ extra-long esophagi are lined with fearsome papillae, which look like curved backward facing thorns, to trap their gelatinous prey.

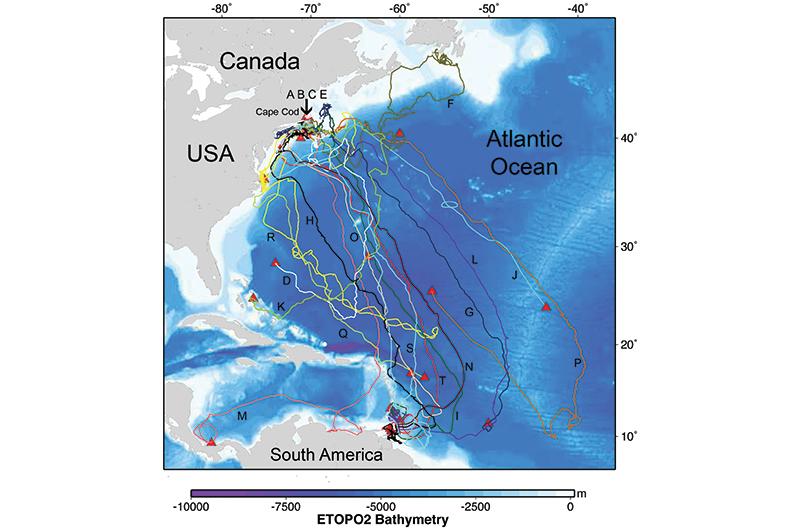

Whatever it is that leatherbacks like about jellyfish, they are willing to travel extraordinary lengths to feed, regularly undertaking the longest migrations of any sea turtle, and of almost any sea creature. One turtle was documented traveling more than 12,000 miles during a migratory season. They are also able to dive to depths up to 4,000 feet thanks to collapsible lungs. Perhaps most unusual, leatherbacks are one of the only reptiles that can regulate their body temperature.

It isn’t totally clear how leatherbacks can manage to keep themselves warm in northern latitudes while other reptiles cannot. There are some clues, though. They have a layer of blubber, like whales, and use counter-current heat exchange in which warm blood runs from their inner bodies out to their extremities, warming up the colder blood that’s running back toward their core. But the biggest factor might be gigantothermy, the ability of large animals to maintain higher body temperatures.

“They’re just big,” said Karen Dourdeville, a research associate at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary on Cape Cod. “So that ratio of body mass to surface...that’s a big part of it. Sheer size.”

Thanks to their size, adult leatherbacks have few natural predators. But it is a long, harrowing, approximately sixteen-year journey to adulthood for the species; their lifespan is unknown, with estimates ranging from thirty to 100 years. The odds are decidedly stacked against the hatchlings, which begin their lives in warm climates – for the Atlantic population that means ocean beaches in Florida, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. Female turtles come ashore at night, mostly to the beaches in the region they were born, and dig holes in the sand to lay a large clutch of about eighty-five fertilized eggs, each roughly the size of a billiard ball. Female turtles lay five to seven clutches each year. That sounds like the makings of a leatherback baby bonanza, but for reasons that are unclear, roughly only half the eggs produce a live turtle.

While adult turtles are aptly described as prehistoric looking, the hatchlings are objectively cute: about three inches long at the biggest, black with white spots and big eyes. Using ungainly paddle-like front flippers that look as big as their bodies, the babies make their way to the ocean, facing predators ranging from dogs and human traffic to birds and wild mammals.

Once they make it to the surf, things are only marginally better. Hatchlings are prey for fish and other larger animals. The upshot is only 6 percent of young leatherbacks make it through their first year. And except for when females return to their birthplaces to nest, they will spend the rest of their lives at sea, much of it in the open ocean, living mostly out of human sight. As a result, there is much that is still unknown about them. But thanks in part to TurtleCam, a spinoff of the SharkCam developed at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) by Amy Kukulya, a principal investigator and research engineer, Dodge and other researchers are beginning to get a closer look at the mysterious species, even following them through the sometimes murky-green sea water around the Vineyard.

TurtleCam is a torpedo-shaped, autonomous underwater vehicle equipped with up to seven different cameras and programmed to communicate with and follow transponder tags attached to marine animals, such as a white shark or a leatherback turtle. For as long as the battery life lasts, the vehicle will follow the animal, allowing researchers to virtually tag along underwater. Kukulya describes it as an epic game of Marco Polo between the camera and the tag attached to the animal.

“Anytime you put a camera on an animal underwater, you always learn something new,” Dodge said. Cameras could reveal where the turtles feed and spend their time in the water column, which could help to prevent entanglements, as well as information about water currents and temperatures, salinity, and whatever other information a scientist may want to collect.

“We really benefit from SharkCam. All the hard work and technology had been spent, we took it and put a turtle spin on it,” said Dodge. The transponder tags initially attached to shark dorsal fins were adapted to stick on leatherback shells with two suction cups. Video taken at sea shows Dodge (who worked at WHOI at the time of the project and still holds a guest appointment there) and Kukulya looking for turtles, assisted by a spotter in a plane. When a turtle was located, researchers attached a transponder tag with a long pole, cheering once the tag was affixed. The turtles notice their temporary adornment, which is released remotely when the work is done, but Dodge said TurtleCam footage shows a negligible impact.

“The turtle definitely notices. It dives as a response,” she said. “‘Something just touched me from above!’ They dive to the bottom usually, swim around for a minute or two, and then just start eating jellyfish again.”

Suffice it to say it takes a lot of jellyfish to feed a half-ton turtle. “They basically are feeding continuously while they are up here,” she went on. Some turtles have been documented eating 120 jellyfish in two hours. The footage shows they favor scyphozoan jellyfish, so-called “true jellyfish” that have existed for hundreds of millions of years. Lion’s mane jellies and sea nettles seem to be their favorites.

Subsisting on a diet of jellyfish, which are about 95 percent water, is extraordinary, Dodge pointed out. “They’re incredible, the only animal doing that,” she said. “They’re eating a very energetically poor diet, yet they turn into these behemoth turtles that travel all the way across the ocean.”

The turtles also seem to be constantly swimming without stopping to rest.

“We don’t know,” Dodge said when asked if the turtles ever rest. “They must rest somewhere, but not the way we think.”

With their complex survival mechanisms, leatherback turtles have long beat the odds. After all, they survived the mass extinction 65 million years ago that killed non-avian dinosaurs and most of the other animals and plants on earth at that time. But in an all too familiar way, humans – and their plastic bags and straws, carbon emissions, auto-piloted boats, and fishing gear – pose a challenge that might prove hard to overcome for even the ocean’s ultimate survivors. “For the impacts we’re talking about, engines on fishing boats, fishing gear that’s really strong, things like that have really only been around for a century. They adapt on a much longer time scale,” Dodge said. “They don’t know what plastic is...they aren’t programmed to avoid plastic. We can’t count on them to compensate.”

The Atlantic population is considered stable to increasing, but leatherback turtles are federally listed as endangered, and scientists studying them have identified several key threats. Fixed fishing gear, the vertical ropes that attach lobster and conch traps to buoys on the surface of the water, is a common cause of death or injury for leatherbacks and other marine animals. According to the New England Aquarium, 220 leatherback turtles have been reported entangled in ropes off Massachusetts since 2005, with an additional twelve known entanglements in 2018. This past July, Vineyard Haven harbor master John

Crocker, assistant Will White, and Andrew Jacobs of the Wampanoag Tribe Natural Resources Department disentangled a leatherback turtle from a buoy line off of Lambert’s Cove Beach.

Vessel strikes are also far too common and often fatal. The turtles use the entire water column to feed and can come up for air as much as 100 times in a span of two hours, Dodge said. This is concerning in high-traffic areas the turtles favor, such as Vineyard Sound and Nantucket Sound. One TurtleCam image shows a leatherback turtle surfacing for air in Vineyard Sound with a view of two Steamship Authority ferries straight ahead.

Plastics are also a growing concern. A 2015 video went viral last year of a researcher extracting a four-inch straw from the nostril of an olive ridley sea turtle in Costa Rica, which led to calls for a ban on plastic straws.

Some leatherback deaths show the combined effect of these hazards. Last October, a 420-pound female leatherback was found on the beach in Brewster on Cape Cod with a gaping wound from an entanglement, likely a rope around her flipper, according to the New England Aquarium. The turtle was taken to the aquarium’s hospital, where it later died. A necropsy showed that she had ingested a large piece of plastic. Another leatherback, a juvenile female that stranded a few weeks later on Cape Cod, also died despite attempts to save her.

The climate crisis poses a host of other concerns, some of which might not yet be known. Rising seas will likely take away nesting habitat, researchers say, and sea turtle nests are intensely tied to temperature. An ideal nesting temperature of 85.1 degrees produces an even mix of female and male baby leatherbacks. Warmer sand produces more females, and cooler water more males. Extremely hot temperatures will result in a complete failure of the nest.

One possible piece of good news is that warming waters might actually produce more jellyfish. But, Dodge said, ample prey is little help without viable numbers of baby turtles.

“They have all sorts of evolutionary strategies for replacing themselves,” she said. “One way is by laying a lot of nests. They’re long lived, supposed to have a long reproductive lifespan. They really have to overcome the odds to live to adulthood, so it’s really hard to see the impacts they have up here, the boat strikes and entanglements, also climate change, ubiquitous plastics in the environment. It’s very concerning. We’re trying to collect as much data as we can.”

Researchers are also trying to spread the word that the turtles are among us. The nexus for sea turtle rescue around the Cape and Islands is the Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, the federally authorized responder to reports of beached sea turtles from Rhode Island to Maine. Since 2009 it has maintained a sea turtle hotline and website, seaturtlesightings.org, which has grown as a tool for spreading the word.

“It’s trying to alert boaters that the turtles are out there,” Wellfleet’s Dourdeville said. Reports come in from some boaters who have struck turtles, she said, while others report a close call. “We know that boaters can hit turtles even when paying attention,” she said. “They swim just under the surface.”

In 2018, Wellfleet partnered with the Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass & Bluefish Derby to distribute information to fishermen about leatherbacks. The annual event runs from mid-September to mid-October, and sightings from the last few years indicate leatherbacks are staying later into October.

“Their organizers have been very interested and very conservation-minded, and they’ve been really good partners,” Dourdeville said. She said 199 reports came in from Derby participants, which doesn’t necessarily mean 199 different turtles. It does indicate a minimum number of turtle/boater interactions. “We got a lot of enthusiasm from Derby participants,” she added, pointing out that anglers are important allies. “Fishermen on the whole, when they’re going out to fish, they’re really good observers. They’re watching the water, they’re watching for signs of fish.”

The hotline also gives a clue to where leatherbacks like to hang out, though Dourdeville points out it is not a formal scientific survey. Popular areas include Lucas Shoal in Vineyard Sound, the Hooter Buoy off Wasque Point, and three shoals off Oak Bluffs. Some of the hotspots coincide with popular fishing areas. “It makes sense that nutrient-rich areas are going to have lots more bait and more plankton, which the jellyfish are eating, so it makes sense that it’s all connected,” she said.

Dodge hypothesized that turtles are drawn to changes in the sea floor, like shoals and channels, which affect jellyfish activity. “It turns out they really like feeding near ferry lanes, which is not a great place for them to be,” she said.

Dourdeville is also concerned about an effort by the Blue Water Fishermen’s Association, a commercial fishing industry group, to change the conservation status of leatherbacks in the northwest Atlantic. In 2017 the group petitioned the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to consider Atlantic leatherbacks a distinct subpopulation of the species, and to recategorize that population “threatened,” which is a step down from the current endangered listing that applies to all sea turtles. The Atlantic leatherbacks’ relative success, compared to their relatives that live in other parts of the world, merits the less stringent protection that goes along with “threatened” status, the group argued. NOAA found that the information in the petition was warranted and began a status review of the species that has not yet been released.

Relative success is the operative word, however. While it’s true that the Atlantic populations have not collapsed as dramatically as Pacific leatherbacks, Dourdeville pointed out that nesting numbers in the Atlantic have fallen in the last ten years. To her, the Pacific leatherback is more a cautionary example than a sign that all is well in the Atlantic. “Their numbers crashed within not too many years, largely, we think, from bycatch and nesting beach disturbance, egg poaching, or development, so that’s a caution for that.”

There are reasons to be hopeful for the turtles, however. Leatherbacks will likely benefit from efforts underway to save critically endangered North Atlantic right whales. The whales travel similar migratory routes as the turtles, from the coast of Florida up to ocean off eastern Canada, and are also injured and killed by entanglement in fishing ropes and gear. This spring a working group of fishermen and conservation members agreed on several whale protection measures, including a reduction in vertical buoy lines and reducing the strength of ropes, allowing whales – and turtles – to break free more easily.

Single-use plastic bag bans are in effect on the Vineyard, Nantucket, and several Cape towns. This spring three Island towns voted to ban plastic bottles in an initiative led by Plastic Free MV, a student environmental action group. They’ve also been working to reduce plastic straw use.

Dourdeville is also hopeful about the partnership with the Derby and recent efforts to remind boaters that auto-piloted boats can’t look out for leatherbacks.

“A lot of people are unaware we have sea turtles – one of those ‘out of sight, out of mind’ things,” Dodge said. “Getting people jazzed about sea turtles and aware we have sea turtles up here is hopefully part of the work I’m doing.

“I think they’re absolutely amazing. And most of the people I’ve talked to who have had the pleasure of seeing one in the wild, it takes their breath away. They are amazing animals.”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)