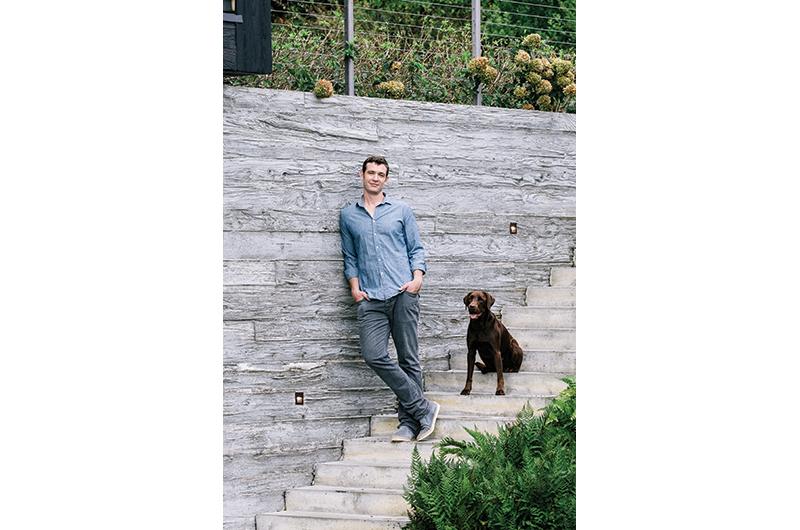

A childhood house, like a game of make-believe, is at once enveloping and beyond reach. Architect Aaron Schiller recently stood in the backyard of his, a mid-twentieth-century A-frame cottage off Middle Road in Chilmark where he spent every summer since he can remember. It’s hard to picture the thirty-five-year-old Schiller as a child, since he is now six and a half feet tall and has a voice like Tom Hanks, but he remembers it.

“I learned to catch fireflies out here. I played soccer out here. I had my first dog here,” he said.

“Two years ago I trimmed back to the wall and I found a size fifteen sneaker,” he said, walking along the stone wall that separates the small backyard from the wilderness of third-growth forest. “Clearly, some brother had thrown some other brother’s shoe and nobody wanted poison ivy. That shoe had probably been there for fifteen years.”

The house originally belonged to his grandparents, both of whom were attorneys who traveled to the Vineyard from Washington, D.C., in the summers starting in the 1950s. His father, Jonathan Schiller, achieved enormous success as an attorney in a firm he co-founded with the nationally renowned litigator David Boies and continued the tradition of bringing his family to Chilmark every summer.

But after decades in the Middle Road house, the family of three sons outgrew the space. All are now married and some have children. Jonathan, meanwhile, had remarried and had a daughter. About ten years ago they all began looking for a place for the next generation, eventually settling on a parcel on a hill overlooking Chilmark Pond and the sea.

The land was all scrub oak and wandering deer, boulders and poison ivy. Schiller, who at the time was about to graduate from the Yale School of Architecture, asked to design the house that would sit on the land. It was a big project, but despite its significance, he said the task was bestowed with little fanfare. “My family’s not that affirmative. It was like, ‘Okay, you asked for it, here’s a lot of pressure, here you go.’”

He dove in. Schiller wanted the new house to capture the essence of the old one: the well-worn smell, the grassy steps down into the backyard his aunt designed, the ladder to the loft above the kitchen where he slept in the summers. But he didn’t want to imitate.

“That house is not our house; it’s grandma’s house,” he said of the venerable A-frame. (His grandmother Patricia Schiller, who died last June at the age of 104, was herself an accomplished woman in a family of high achievers. Her obituary in the Vineyard Gazette described her as “a lawyer and professor who became internationally famous as the founder of the American Association of Sex Educators,

Counselors and Therapists.”)

“What this house is is a culmination of three generations of experience,” he said standing in the shade of his grandma’s blooming rhododendrons. In other words, he had some big shoes to fill.

In any building project an architect has to juggle the desires of the clients and find ways to incorporate different points of view. It’s rarely simple, and in this case it was complicated by the fact that all of the clients were also family.

“There were a lot of different voices. I had to design for two brothers, a little sister, a stepmother, a father. They all wanted something different,” Schiller explained. He was also designing for his new wife, Anna, and for people who don’t yet exist, including his own possible future children, whom he invoked again and again while touring the space.

For the youngest brother in a prosperous clan, designing the home was a somewhat intimidating feat. “It’s a very competitive family,” he said with a laugh. “You have to do good work or you’re going to be told you’re not doing good work. And no one wants to be told that.”

There were presentations, lengthy conversations, and a few disagreements, naturally. Among them: the number of televisions. “One brother wanted every room to have TVs, but my father said the Vineyard is a place where you read,” said Schiller. (The brother apparently prevailed: there are several TVs, including a substantial weatherproof outdoor one on the bottom level.)

There were also Schiller’s personal goals to consider, both as a member of the family who would use the house and a budding architect trying to launch his career. “The thing about the architect’s ego is that you fundamentally need it on some level,” he explained. “You’re trying to build something presumably out of nothing, right? You have to have confidence to do an act like that.”

In all, the house, which he designed in collaboration with his Yale professor and mentor Alan Organschi of Gray Organschi Architecture, would consume two years of his life and serve as his architectural debut. He finished it in 2016.

It is substantial at 6,000 square feet, especially when compared with the A-frame of his youth. The jet-black structure is wedged into the South Road hillside (inspired by up-Island bank barns) and peers out over the ocean with great windows like the eyes of an insect. An expanse of solid-black charred wood wall stretches along the land-facing side. As you advance toward the massive front door, the black planks begin to separate slightly, offering glimpses of the interior and the sea beyond. When the door sweeps open, it reveals a view of the pond and the ocean through the opposing wall of glass.

“The house begins to open up and become more transparent, and then you start to understand,” Schiller said. One of the goals of the design was to promote family integration: all bathrooms and closets are meant to be shared, and community spaces dominate the floor plan. And in every way, it is built for giants. The brothers are all about six and a half feet tall. They grew up playing basketball at the Chilmark Community Center, and all went on to play college basketball after that. Their father also stands at over six feet. So surfaces throughout the home are generally about two inches higher than standard. Meanwhile, the orientation and building materials – wood replaces steel wherever possible – greatly reduce the need for heating and air conditioning.

The house has won its designers a great deal of press – The New York Times Style Magazine devoted about 1,300 words to the black siding alone – and has led to multiple commissions for Schiller’s young firm.

“We’re a little overwhelmed right now; we’re hiring more people in New York,” he said.

On a rainy Friday afternoon in July, Jonathan Schiller reclined in the living room of the Chilmark house taking work phone calls. Chair of Columbia University’s board of trustees, there is a steeped-ness about him. Years ago, he recalled, he was surprised to learn that his son Aaron wanted to be an architect, and he heard the news secondhand.

“He made that clear to my law partner when he was still in college,” he said. “David Boies said to Aaron that he looked forward to Aaron coming to the firm, and Aaron said, ‘I’m going to become an architect.’” Boies tried to talk the young designer out of his plan, but the famous litigator failed to convince his young son, Jonathan said with a chuckle. “David was disappointed.”

Though Jonathan had his doubts about the choice to go into architecture, saying “it’s a challenging field to work in,” he’s convinced now that his son will thrive. He said he likes the way light moves through the new house, how it contrasts with the striking black exterior. The house returns at every point to the hillside behind it, lending it a sense of permanence.

“Once I gave him this mandate, he then developed a very thoughtful plan and he executed on it,” he said.

The rain stopped and the living room filled again with light as he reflected on his children. “They’re each creative, they have a lot of initiative, and they bring me a lot of pleasure,” he said. “Pride.”

It’s obvious that Schiller, too, feels pride about the home he poured himself into for two years. He knows the placement of each boulder in the backyard, and he built much of the furniture in the family house himself. He has a quotable tidbit ready for every aspect, from a pressed concrete wall to a bathroom skylight. Art created by his friends in New York and on the Vineyard hangs throughout.

And built into the house itself is an idea that somewhere in the future, another child yet to be born waddles into Chilmark Pond, lifts a shell up from beneath its surface. A blink and the child is in middle school, roasting marshmallows over the great stone fire pit. Then about to go to college, recovering from a bad sunburn in the shade of the lower story’s porch.

“Designing this house,” Schiller said, “is like designing a jewel box.”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)