In the late 1970s, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) drilled an 860-foot hole straight into the heart of the Island’s sole-source aquifer. At the time, Vineyard neighborhoods were filling up, fueling concerns over the importance and vulnerability of ground water. The deep hole was one of many observation wells that were used to collect data and piece together a picture of an almost entirely unseen part of the Island: a vast, complex reserve of fresh water underground that moves and breathes with the seasons and quietly sustains everyday life on the surface – from pools and gardens to clean clothes and our morning coffee.

Almost forty years after its release in 1980, the USGS study by David Delaney remains the only comprehensive survey of groundwater hydrology on the Island. Many of its findings still hold true today. At the most basic level, Islanders can rest assured that the aquifer won’t run out anytime soon: the billion or so gallons pumped annually barely scratches the surface of the roughly 150 billion gallons estimated to lie below the surface. (That’s 227,272 Olympic-size swimming pools or roughly the amount of coffee the United States might consume in sixteen years at present levels.)

But that’s not the end of the story, especially up-Island and along the shores, where ground water can be notoriously variable. Though the Island’s water quality is still among the best in the state and protections have become much more robust in the last half-century, contamination from everyday activities remains a constant threat. And as is often the case in resort communities, development and the effects of climate change present new hurdles for town planners and residents alike.

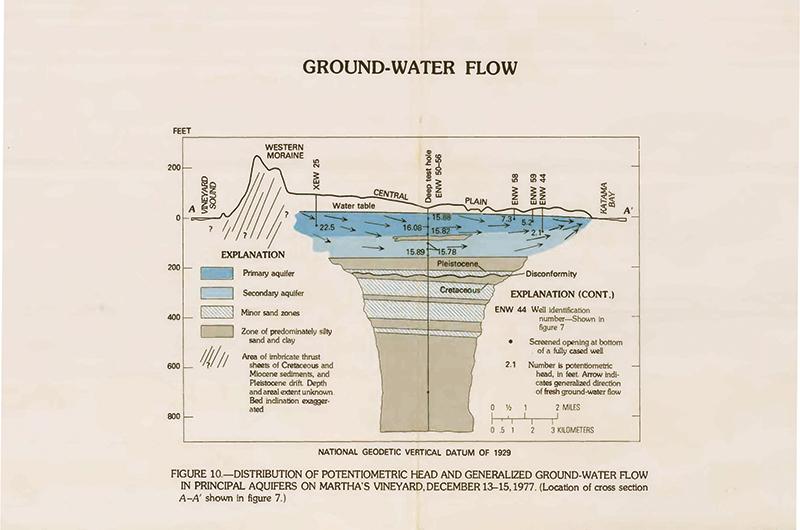

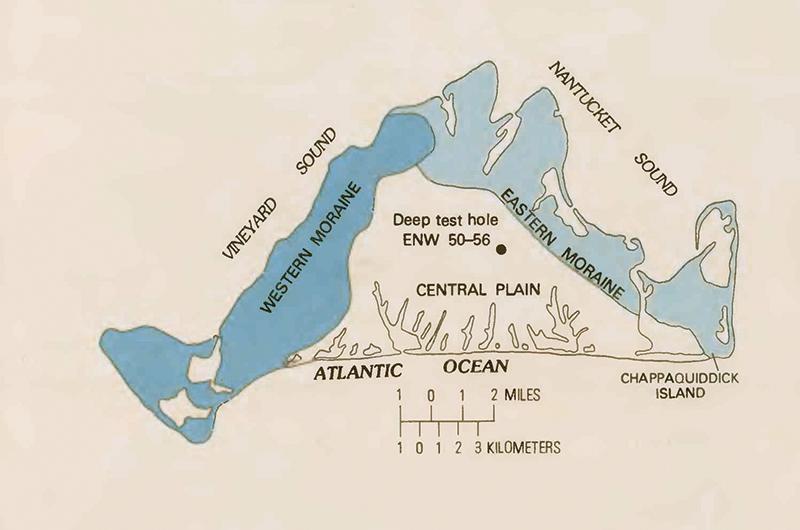

The USGS study mapped the boundaries and characteristics of the Island’s main aquifer, which covers more than forty square miles and supplies about one billion gallons of water annually to Edgartown, Oak Bluffs, Vineyard Haven, and parts of West Tisbury and Chilmark. It also confirmed what many people already knew – that despite its excellent quality overall, Vineyard drinking water often contains extreme levels of iron and manganese, and fresh water supplies up-Island can be hit-and-miss. The deep hole in the Manuel F. Correllus State Forest in Edgartown revealed freshwater as deep as 475 feet below sea level, including a primary aquifer extending about seventy feet below sea level, and a secondary aquifer of lesser quality beginning about twenty feet farther down. Even deeper water may remain from an earlier aquifer locked away for eons.

Nearly every drop of fresh water from a hose or tap on the Vineyard is pumped out of the ground. And despite persistent tales of an underground stream originating in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, all ground water on the Vineyard arrived here as rain. These two conditions allowed residents in 1987 to successfully petition the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to designate the Island water supply a sole-source aquifer, an official status that means every local development project that receives federal funds is subject to EPA review. This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of that decision.

Despite the designation, however, it’s not quite accurate to say the Island has only one aquifer. It’s true that Edgartown, Oak Bluffs, and Vineyard Haven get almost all their water from the sand and gravel deposits known as the central outwash plain, where ground water moves at a relatively brisk pace (about a foot per day), ultimately discharging into the ocean. But it’s a different story in the hills of the western moraine that extends from Vineyard Haven to Aquinnah, in the recessional moraine that created the Elizabeth Islands, and to some extent in the eastern moraine that includes Chappaquiddick.

Those areas formed in several different stages as glaciers plowed up existing layers of earth, rearranged them like a folded cake, and then dumped varying amounts of rock and gravel till on top. The effects are most pronounced up-Island, where seemingly random layers of clay, sand, and gravel create countless small aquifers at depths ranging from around 15 to 350 feet below the surface. It’s even possible in such a complex system for water drawn from one well to deplete another nearby.

The small aquifers up-Island still baffle even the most seasoned groundwater experts. “I don’t think anybody understands the interconnectedness of those,” said Bill Wilcox, a former water resource planner for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC) who led a number of hydrologic studies on the Island beginning in the 1970s and did similar work through the Cape Cod Cooperative Extension in the 1980s and ’90s. He noted that the western moraine even has some outwash plain mixed in, and likely contributes surface runoff (and possibly ground water) to the main aquifer. The moraine might include isolated mini-aquifers, he said, or there might be connections at certain depths but not at others. No one really knows.

Nor can anyone say how much ground water is stored in the moraines, where the vast majority of homes get their supply from private wells. The MVC estimates that private wells across the Vineyard produce about as much as the three municipal suppliers – in Edgartown, Oak Bluffs, and Vineyard Haven – combined. Counting one well per dwelling, and excluding the approximately 10,400 public water connections as of last year, one could estimate about 8,215 private wells on the Vineyard, the vast majority in West Tisbury, Chilmark, and Aquinnah.

As it happens, more than 2,500 of those wells were installed by Dave Schwoch, a professional well driller who grew up in Minnesota and moved to the Vineyard in 1988. Visit any number of construction sites at the right time and it’s easy to spot him next to the towering Island Water Source drill that for twenty-five years has essentially made it possible to develop new lots up-Island.

On a clear morning in April, Schwoch was busy pulling levers and positioning heavy equipment at the edge of a field near Cedar Tree Neck in West Tisbury. Even before starting the drill, he easily described the first 200 feet of earth below the surface: 100 feet of sand and gravel, followed by thirty-foot layers each of finer sand, mixed sediment, and clay, then another layer of sand and gravel. He assumed water could be found both above and below the clay.

“Most of the time I have a fairly good idea of what might happen,” he said, although he noted some surprises over the years, including a layer of ancient shells about 160 feet down that he has hit a number of times near the shore in Edgartown, and ancient wood preserved at depths of up to 300 feet.

It appears the early up-Islanders also had insight into the world below their feet, as indicated by the positions of North, Middle, and South Roads, which follow veins of more easily accessible ground water. “When we start going further off the roads, anything can happen,” Schwoch said. “It’s not necessarily that you won’t find water, but it might be a little more difficult.”

Along those lines, Schwoch has also observed how a growing scarcity of land has led Islanders to build in more remote locations where ground water (and wells) tend to be deeper. It’s not uncommon in some of the hillier areas of West Tisbury and Chilmark to drill multiple holes before finding reliable water.

“It’s rare that we go over 250 [feet] in a typical year,” said Schwoch’s colleague and Island Water Source’s owner, John Clarke, who came to the Vineyard in the 1990s. The deepest private well on the Vineyard descends 400 feet through Abel’s Hill in Chilmark. But in the last year alone, Island Water Source had drilled three wells exceeding 360 feet. In his office overlooking the Martha’s Vineyard Airport, Clarke explained that once you get off the moraine, finding water is relatively easy. “Anything around here would be sixty to seventy feet,” he said.

The downside, if there is one, to having a vast, relatively shallow and easily accessible aquifer is that the porous nature of soils in the outwash plain may increase the risk of contamination. Getting up from his desk at the town hall, Edgartown health agent Matt Poole retrieved an overflowing folder, about twice the size of a city phone book, filled with reports and lab results going back to 1996. That was the year that Craig Saunders, a groundwater consultant who previously worked for the EPA, was doing a routine inspection of an underground fuel tank site and discovered a massive plume of dry-cleaning solvent emanating from the former Takemmy Laundry at the Airport Business Park.

“I tested all around the laundromat, and the soil was just hot with PCE,” Saunders said, referring to the chemical tetrachloroethylene, which the EPA classifies as a probable carcinogen. The plume stretched out a mile to the south, meaning the chemical had been mishandled for years. Saunders eventually handed off the project to a private firm, which tried several methods of remediation, including injecting a powerful oxidizing agent into the ground to break down the chemical. More than twenty years later, the largest known spill ever reported on the Vineyard is still being monitored. “They are just in the process of putting it to bed now,” said Poole.

There were other notable incidents. The contamination of drinking water downhill from Up-Island Automotive in West Tisbury led to the installation of seventeen monitoring wells and a number of hazardous materials surveys beginning in 1987 to track the plume, although it was never traced back to a source. At Dockside Marina in Oak Bluffs on a summer morning in 2007, a fuel delivery worker accidentally began filling the wrong tank, then stepped out of sight behind a fence. “Fuel discharged upward from the tank in a geyser-like fashion and rained down on the outdoor bar, deck, and seating area of the Sand Bar & Grille,” according to an official account filed with the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Fortunately, that site was close enough to the Oak Bluffs Harbor not to pose a serious threat to ground water, which is hardly a silver lining from a marine standpoint.

Longtime Islanders also recall stories of indiscriminate dumping at the former Martha’s Vineyard Naval Auxiliary Air Station, which operated during World War II and later became the Martha’s Vineyard Airport. And at a plastic machine parts company that operated in the nearby business park in the 1950s. Saunders, who has studied contamination across the country, said national defense sites are very often among the worst offenders, but he doubted whether the Naval station here caused any major problems since it existed for only a few years. “They buried some stuff, there’s a lot of conjecture,” he said, but he maintained that the dry cleaning incident was by far the worst he has seen on the Vineyard.

Partly because of its location over the sole-source aquifer, the airport and business park are now so thoroughly monitored for groundwater contamination that it would be hard to miss anything left over from the 1940s and ’50s or any new leakage from the up to 280,000 gallons of fuel and oil stored there at any given time. (Though it bears remembering that the dry cleaning spill was overlooked for years despite at least periodic testing.) Like every wastewater facility on the Island, the airport’s wastewater treatment plant, updated in 1992, includes a number of observation wells to make sure sewage effluent is not escaping and traveling toward the great ponds. A fourth series of wells was installed at the airport this spring to keep track of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), a bioaccumulant and possible carcinogen that is used in fire prevention drills and has contaminated drinking water on the Cape due to its use at the Barnstable County Fire and Rescue Training Academy.

It’s safe to say that rules for managing wastewater, oil, landfills, and other hazardous materials enacted in the 1970s and ’80s have made contamination in the form of chemicals on the surface much less routine. But oil spills and other serious incidents still occur with disturbing frequency on the Vineyard. The state lists 241 hazardous spill sites in Dukes County since 1986, including at a number of existing gas stations, and many incidents involving home heating fuel. The vast majority of reported spills occur down-Island, but even Gosnold has made the list.

“Once you get in that system there is no escape,” said Edgartown health agent Poole, who has seen his share of household fuel spills over the years. “They don’t let you drift away.”

By happy coincidence, the state forest that surrounds the airport and covers about 5,200 acres in the center of the Island has helped preserve the resource by limiting development and filtering out some contaminants. Forward thinking land-use regulations and a lack of major manufacturing has also spared the Vineyard much of the environmental havoc seen on the Cape and elsewhere in the twentieth century. But perhaps the greatest recent benefit to the aquifers came with the retirement of every landfill in Dukes County beginning in 1993. All of the Vineyard’s trash – about 19,000 tons per year – is now shipped to the mainland for recycling or incineration; hazardous waste collection days, a tradition going back to 1985, also help keep household chemicals out of the ground.

As with most landfills in the state, the ones here were constructed without the plastic liners and drainage systems now required to protect ground water. However, after essentially being condemned by state regulators, the largest ones were capped with a sturdy plastic material resembling roof shingles that sheds rainwater and must be monitored and maintained for at least thirty years.

“I’ve never heard of a failure of a cap,” said Don Hatch, manager of the Martha’s Vineyard Refuse Disposal and Resource Recovery District, which operates transfer stations in Edgartown, West Tisbury, Chilmark, and Aquinnah. But he won’t

say he knows how long they will last. “Of course, when they put it down they said forever.”

Jane Chittick has her reservations. She served on Island committees in the 1980s when everyone knew the end was coming for the town landfills but no one had quite figured out how to bridge the gap between on-Island and off-Island disposal. She led the charge against a proposal to bale Island garbage in plastic and store it indefinitely in Vineyard Haven, arguing among other things that the plastic would inevitably fail. Now she doubts the caps will protect the aquifer forever. “At some point in time, maybe hundreds of years from now or longer, it will be polluted,” she said. “It’s only a matter of time.”

Saunders, for his part (he discovered the infamous dry-cleaning plume), sees the glass half full. “There have been small problems along the way, but water quality has been pretty good,” he said. “We’re blessed here with having the lack of large industry, really plentiful rainfall, very easily tapped aquifers.”

Not everything that can spoil drinking water originates at the surface. The state requires that all public water supplies, including those on private wells, such as at the tribal housing in Aquinnah, the West Tisbury School, and Chappaquiddick Beach Club, be tested throughout the year. Some may call it a double standard that private wells are exempt, but many of the official thresholds, including for naturally occurring iron and manganese, have more to do with taste and appearance than safety, and homeowners may vary in their tolerance for red-stained laundry and black rings in their bathtubs. That red slime in your toilet tank, for instance, is likely iron bacteria, a non-harmful but unsightly result of Vineyard geology and private wells.

A combination of acid rain and naturally acidic soils creates higher than normal acidity in Vineyard aquifers, and many a shower up-Island has turned greenish-blue from copper leached from the plumbing. Some homeowners also report green-tinted and brittle hair resulting from the pipes, which often don’t fare too well themselves. “The plumbers are basically sick of repairing pinhole leaks,” said Poole.

Water departments and some private homes add various chemicals at the source, including sodium hydroxide, which lowers the acidity of ground water and helps reduce the corrosion of lead and copper pipes that may cause contamination at the tap and serious health issues depending on the level of exposure. Island water departments also regularly flush portions of their pipe networks to prevent leaching of PCE, the same chemical in the Takemmy Laundry plume.

The so-called natural contaminants abound. “We’ve found high instances of just about everything that you can have,” said Bret Stearns, director of the Wampanoag Tribe’s Natural Resources Department, who manages the Wampanoag Environmental Laboratory on the shores of Menemsha Pond in Aquinnah. The lab is the only one of its kind on the Vineyard and tests between 500 and 1,000 samples per year, many of them for private homeowners. But he also noted that many hazardous materials such as oil and solvents won’t turn up in a test unless a lab technician knows to look for them.

Last but certainly not least, there is salt. Underneath much of the Island, fresh water gives way to brine. In general, the Island aquifer floats atop a layer of denser salt water, sagging in the middle and cresting slightly as it presses downward and outward, creating a freshwater lens. The lens becomes so thin near the shore that in some wells on the Vineyard the fresh water rises and falls with the tides.

“There’s not much holding the ocean back except the pressure of the freshwater on the ground,” said Clarke of Island Water Source. In an ironic twist, therefore, while there is virtually no chance of using up the Island’s freshwater supply, there may be unintended consequences to overindulging in the aquifer’s abundance. Specifically, irrigation and other heavy uses can reduce pressure in the aquifer, drawing the saltwater boundary up from below and in from the shore. This may in turn lead to saltwater contamination (also known as saltwater intrusion), a common nuisance for seaside resorts and a health concern for people with heart conditions.

Nor is it an even trade. Coastal aquifers have a quirky trait, known as the Ghyben-Herzberg principle, which states that for every one foot drop in the freshwater table, the saltwater boundary below will rise about forty feet due to the difference in density. To compensate for those conditions, in locations where the aquifer might be thin, Island Water Source often installs what they call an “upside-down well,” which draws from the top of a water source while the pump rests at the bottom. That helps keep salt water out of the well and air out of the pump as the lens expands and contracts over time.

“That’s a good way to go, and it will work perfectly for a house,” said Clarke. “But if you start to irrigate your yard with it, you start to pull thousands of gallons a day out of it, it won’t take too long for the salt to come up.”

The outwash plain aquifer itself rises and falls about five feet during the year depending on rainfall. More than 40 percent of the precipitation on the Island evaporates, runs off into streams and ponds, or is taken up by plants. The rest – about twenty billion gallons per year – percolates into the ground, mostly during the fall and winter when plants aren’t growing. As a result, Island water tables reach their height in spring and early summer, followed by a period of decline in the growing season. Throughout the year, ground water seeps into coastal ponds and eventually the ocean, maintaining a rough equilibrium of water in and out of the aquifer.

New public wells since the 1990s have trended closer to the state forest, which helps ensure a high-quality supply and lowers the already remote chance of increased withdrawals from those wells affecting the saltwater boundary. Bill Chapman, superintendent of the Edgartown Water Department, called saltwater intrusion a “non-issue” for the public wells in his town, given their depth and design. Build-out projections for 2035 still have him shopping for new sites, but that’s mostly to meet the summertime demand, when all four primary wells (minus one for backup) run at peak capacity. “It can be a little nerve-wracking getting through a Fourth of July week,” he said.

But given the effects of climate change already underway in the region, the future is less clear for the outlying private wells. Sea level at Woods Hole has risen about nine inches since 1930, and is expected to rise as much as 3.4 feet by 2070. A three-foot rise on the Vineyard would likely raise the freshwater lens an equal amount, meaning a good number of private wells near the shore will turn brackish. Those remaining along the coast may then face a greater risk of saltwater intrusion.

At the same time, climate scientists also predict up to a 20 percent increase in precipitation by 2100, which could further raise the freshwater table, especially if most of that precipitation falls in the winter as expected, since more of it would reach the aquifer. But it’s hard to predict the cumulative effects of more precipitation, hotter summers, and a longer growing season, all of which is projected for Massachusetts. Hotter summers, for example, could lead to heavier irrigation, which could in turn increase the risk of saltwater intrusion.

Saunders noted that from a supply perspective, the combined effects of climate change on the aquifer most likely won’t spell disaster, and could even be an advantage.

“Unless,” he added, “you live in Vineyard Haven. Then you’re under water because of sea level rise – which people aren’t really planning for, even on the progressive Vineyard.”

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)