In the fall of 1832, Dr. Jerome V.C. Smith was crossing Mill Brook in West Tisbury when a disturbance in the water caught his attention. A passionate angler, Smith was stunned by the number of brook trout he saw and recalled the experience in his book, Natural History of the Fishes of Massachusetts, published the following year.

“In no place, however, do we remember to have seen them in such abundance as in Duke’s county, upon Martha’s Vineyard,” he wrote. “It was here in the month of November last, and of course in their spawning time, while returning home from a ramble among the heaths and hills of Chilmark and Tisbury, that crossing the principal brook of the island, our attention was attracted towards the agitated state of the waters, and never do we recollect so fully to have realized the expression of its being ‘alive with fish,’ as on this occasion.”

Today the Vineyard is closely associated with the scenic ocean beaches that lie at the heart of the Island’s vacation destination appeal. Less visible, and possessing a subtle charm distinct from the crashing surf, are the brooks and streams that originate as small rivulets in sun-dappled Island woodlands and swamps and flow into ponds or the sea. The Island is home to some twelve such “rivers” and more than sixty ponds, which include kettle ponds, salt ponds, and man-made impoundments, according to an incomplete 2015 survey by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC), the Island’s regional planning and permitting agency.

While many of the smaller streams go largely unnoticed, man-made alterations to the water flow of Mill Brook, most notably Mill Pond, have been the focus of a long-running debate in West Tisbury that encompasses the natural, economic, and cultural history of the waterway.

In June a specially appointed West Tisbury committee presented its forty-seven-page “Mill Brook Watershed Study Report and Recommendations” to a roomful of Island officials and residents. The report, the culmination of four years of meetings, data gathering, and hard work, is expected to form the basis of continuing study of Mill Brook and its associated 2,928-acre watershed, and provide a framework for future discussion – and perhaps action – to protect the brook.

Within these waterways, anglers may still find various native species of fish, including chain pickerel, bullhead, and perches. But it is the native brook trout, Salvelinus fontinalis, that is most closely associated with New England and the natural beauty of its streams. And it is they, according to the Massachusetts Audubon Society, that serve as “indicators of the location of relatively undisturbed environments.”

However, not all trout are equal reflections of their environment. Twice each spring, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MassWildlife) stocking trucks deliver a mix of approximately 800 farm-raised rainbow and eastern brook trout to three West Tisbury ponds: Duarte, Uncle Seth’s, and Mill Ponds, and rainbow and brown trout to Upper Lagoon Pond at the head of Lagoon Pond in Oak Bluffs. In the past, tiger trout also have been stocked in the ponds.

Meanwhile, the Island’s brook trout, fish that have never seen pellet food or the inside of a tank, maintain a tenuous grasp on life in cool, secluded pockets of water along Island streams.

In September 2012, MassWildlife Southeast District Fisheries manager Steve Hurley and a team conducted a fisheries survey of Mill Brook and its tributaries in West Tisbury “to officially document reported wild brook trout populations.” The brook flows 2.7 miles from its headwaters in Chilmark to Mill Pond in West Tisbury and, along with other species of fish, the team found reproducing wild brook trout in the upper reaches of the brook and in two small tributaries. The conclusion was that wild brook trout populations were persisting in the Mill Brook watershed where cold water habitat remains, “but their access to tidal areas is blocked by numerous dams and barriers,” thereby preventing them from adopting an anadromous lifestyle wherein the trout, known locally as “salters,” migrate between the river and the sea.

Even before Smith’s 1832 visit to the Island, the natural equation that for thousands of years provided the Island’s earliest inhabitants with a source of freshwater fish was being altered by new technology brought by the British. The newcomers harnessed streams to produce power for mills and industry, slowly at first and then increasing in pace with the Industrial Revolution, altering the ecology of streams that once flowed freely.

Dr. Charles E. Banks, author of a three-volume History of Martha’s Vineyard, published in 1911, refers to the Tiasquin [Tiasquam] River as the site of the Island’s first gristmill, built by Benjamin Church of Duxbury in about 1668. The mill was in operation for almost two centuries. Today the dam and the pond it created – Look’s Pond, named for the family whose members operated the mill for 156 years – remain. The first dam and mill on the Mill Brook was also erected in the seventeenth century.

But it was in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, after Smith saw the river so memorably “alive with fish,” that the pace of development of the Island’s streams really took off. Had Smith been able to return even fifty years after the visit he chronicled, he would have found much had changed. As David R. Foster wrote in his 2017 book A Meeting of Land and Sea: Nature and the Future of Martha’s Vineyard (Yale), the shift from agriculture to industry in the northeastern states “was experienced on the Island as a modest boom in manufacturing and processing.”

“New water-driven mills were erected and old colonial ones were expanded through the hills and valleys of Chilmark and West Tisbury. Activity peaking toward the middle part of the century included new gristmills at Look’s Pond, Fulling Mill Brook (1850 by Samuel Tilton), Roaring Brook (1849, Francis Nye), and along Mill Brook (Daniel Fisher’s dams and mills at Crocker, Fisher, and Athearn Ponds, circa 1860), and construction of the Smith and Barrows brickyard at the outlet of Roaring Brook (1850) and

Paint Mill (1847–49) on the brook of that name in Chilmark.”

Remove vegetation and trees that provide cooling shade, block streams with dams, constrict water flow with road culverts that are too narrow or poorly installed, create impoundments that absorb solar energy: do any or all of that and brook trout populations, as well as other species, including herring and American eels, will be affected.

“They back things up, they cause silt and fine organic matter deposition because the water slows down; the anadromous fish can’t get by them,” is how Bill Wilcox described the effects of the dams and impoundments. Wilcox is a retired MVC water resources planner and an advisor to the West Tisbury Mill Brook Watershed Management Planning Committee, which recently released its report on the brook ecosystem.

“It’s just a nightmare of impacts,” he said.

The biggest impact of the dams, however, is on the temperature of the water. Brook trout spawn optimally at 51 degrees, and do well at 59 degrees. Water temperatures above 68 degrees for any length of time threaten the survival of any brook trout population. Five years ago, the watershed management planning committee began measuring water temperatures at nine locations along the Mill Brook system during the summer months. According to the 2017 results, from June 16 to September 10 the maximum water temperature exceeded 78 degrees in three locations and rose above 83 degrees in three other locations. The highest temperature was 86.03 degrees below Priester’s Pond.

In its October edition of The Conservation Almanac, the Vineyard Conservation Society (VCS) published the 2017 Mill Brook water temperature graph and highlighted the temperature spikes. “Beyond the physical obstructions, which can be partially mitigated by workarounds like fish ladders, the ponds create thermal barriers separating portions of stream that could otherwise be good habitat for heat-sensitive species,” VCS noted. “It is not nearly as visually apparent as a highway running through a forest, but these hot spots are in effect yet another form of habitat fragmentation.”

The few wild trout that remain are, like the other native fresh-water species on the Island, the genetic descendants of fish that arrived following the last ice age. The Laurentide ice sheet emerged from the Arctic and moved south until it reached a latitude where the rate at which it melted in the summer roughly equaled the rate at which it advanced in the winter. That line was about even with what is now Martha’s Vineyard and Long Island. During the tens of thousands of years it paused there, the massive, dynamic flowing sheet of ice and the glacial rivers running off it deposited the rocky debris it had scoured from the landscape over which it traveled. These, in turn, shaped the Island, from the massive boulders strewn along the north shore and morainic Chilmark hills, to the sandy outwash plains of Edgartown and West Tisbury at the east and south ends of the Island.

At the peak of the last ice age some 26,000 years ago, so much water was stored in ice that the sea level was 400 feet below modern levels. The East Coast continental shelf, including Georges Bank, the fabled fishing ground east of Cape Cod, “was dry land dotted with ponds and streams,” according to Edgartown native and research biologist Clyde L. MacKenzie Jr. and Thomas Andrews, zoology professor, who described the processes at work in an article titled “Origin of Fresh and Brackish-Water Ponds and Fishes on the Vineyard,” published in the Dukes County Intelligencer in 1997.

A variety of fish species existed beyond the ice sheet. Over a period of 8,000 years, as the earth began warming and the glacier melted and receded, the fish followed a drainage system of channels created by melting ice and moved inland. Their range expansion ended as a result of the attendant rise in sea level.

Rising waters filled in depressions and gave birth to Vineyard Sound and Nantucket Sound and left Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket islands. Large chunks of ice embedded in the debris melted to form depressions and kettle ponds – think of Ice House and Seth’s Ponds in West Tisbury. “The freshwater fishes in the ponds and streams of the islands were locked in place, unable to leave, ‘imprisoned’ behind a saltwater moat, the Atlantic,” MacKenzie and Andrews wrote.

Fish may be introduced or migrate to a water body in a variety of ways; not all arrived by way of ancient streams. But those considered native to the Vineyard include chain pickerel, brown bullhead, yellow perch, white perch, golden shiner, banded killifish, tessellated darter, swamp darter, and brook trout. Brackish water fishes include white perch, striped killifish, and mummichog. Large numbers of herring and eels, a seasonal and reliable bounty even into the last century, arrived annually from the ocean-seeking ancient routes to their fresh water source.

When he was a young man growing up in Edgartown in the 1940s and 1950s, MacKenzie, who would later go on to become a researcher for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Marine Fisheries Service, said the emphasis was on saltwater fishing, but from time to time he and his friends fished for freshwater species in Fresh Pond in Oak Bluffs and Watcha Pond in Edgartown.

Speaking of his youthful fishing companions Bert Mixter, Jimmy Ripley, and Kenny Osborn of Edgartown, he said, “Bert and the rest of us fishermen took our catches for granted. We would have been astonished if someone had told us about the ice age origin and the centuries-long journey taken by the ancestors of the pickerel, yellow perch, and white perch we caught and ate so matter of factly.”

In recent years Mill Pond in West Tisbury has been at the center of an occasionally heated and emotionally charged public debate. On one side are historical preservationists who believe that the 300-year-old pond at the top of Edgartown–West Tisbury Road is an integral part of the character of the town. On the other side are conservationists and wildlife experts who point to the return of spawning herring and an overall improvement in fish habitat and fish species, including salters, with the removal of ancient and obsolete dams. They ask whether Mill Pond and the other impoundments up and down the river have outlived their usefulness, given their impact on the health of

the 6,000-year-old stream ecosystem.

In the state survey, Hurley’s team documented the continued presence of remnant populations of native trout, and recommended that “consideration should be given to removing unneeded dams or culverts…in the Mill Brook system to increase river connectivity and fish passage and improve cold water stream habitats.”

In general, Hurley said in a recent conversation, the brooks and streams of Martha’s Vineyard are in relatively stable condition. Most of the habitat degradation is caused by historic impacts, such as dams and road culverts. Additional issues include road and agricultural runoff and atmospheric deposition.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that the dams’ useful purpose is pretty much aesthetic,” said Wilcox of the town watershed management planning committee. “And if there is some way we can begin the process of figuring out how to remove some of them – through I’m not sure by what means – that, I think, is the linchpin that separates a much higher quality resource from the one that we have now.”

Many Island streams and ponds run through private properties in whole or in part and are inaccessible to the public, but not all. Fulling Mill Brook in Chilmark, named for a fulling mill established prior to 1694, is at the core of the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission’s almost fifty-acre Fulling Mill Brook Preserve. The property stretches from its trailhead on Middle Road to South Road, where the brook crosses South Road and enters upper Chilmark Pond. Recreation activities allowed include hiking, horseback riding, mountain biking, fishing,

and hunting.

In recent years, public and private conservation organizations and landowners have begun to seek ways to improve stream management. In April 2015 The Trustees of Reservations (the owner) and Eric and Molly Glasgow of Grey Barn Farm (the lessee) removed boards from a spillway used to create a farm pond on the Tiasquam dam just above Tisbury Great Pond. Within weeks herring had begun moving up the stream – only to encounter their next obstacle, Look’s Pond dam. That fall mallards and black ducks were feeding on a stream that had begun to regain its natural appearance. Alarmed by the futile efforts of herring to continue their upstream journey, the following year Geraldine Brooks and Tony Horwitz, owners of the property that includes the Look’s Pond dam, worked with state and conservation officials to construct a fish ladder around the stone obstacle.

At the head of Mill Brook, Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation has received state grants to replace narrow, improperly situated culverts that impede the flow of the brook under Old Farm Road in Chilmark with new culverts that would improve stream connectivity. The plan is opposed by the Dunkl family, who previously ran the Chilmark Spring Water Company. The Dunkls worry it would affect their well, despite assurances by the conservation organization’s well-drilling expert to the contrary.

What the future holds for the dams and man-made obstructions along Mill Brook is unclear, but it seems certain the debate over Mill Pond will continue for some time. In July 2017 the town of West Tisbury placed a brass plaque affixed to a granite boulder next to Mill Pond that describes its industrial history in detail. The monument was funded by the Friends of Mill Pond, a group adamant that the pond be preserved.

But if Mill Brook and other impeded Island streams ever do again run free, the fish are waiting. Despite fifty years of stocking with hatchery-raised trout, Hurley suspects based on research that “the bulk of brook trout populations found on the Island are probably remnant native populations, rather than stocks of hatchery origin.”

In A Meeting of Land and Sea, Foster also pointed to recent studies that show salters persist in a dozen tiny brooks across the Vineyard. “From these tenuous outposts, it is poised to rebound and claim a greater role in waters that over recent history have been stocked with non-native fish, ironically to improve local fishing.”

Evidence of that potential exists. Just this April, Tom Robinson of Vineyard Haven was fishing for white perch in a Tisbury Great Pond cove when, to his great surprise, he hooked a salter, the first he had ever seen.

While most “brookies” are small in comparison to salters, often no more than six inches in length, all trout fishermen agree that the uniform characteristic is beauty.

Almost two centuries after Smith cast to trout in Mill Brook, Tim Sheran of Vineyard Haven speaks with equal passion and appreciation for the Island’s native trout. Sheran, a bicycle shop owner and tile installer, recalls a trout he caught in Island waters – a salter he hooked on his first cast in a brook-fed Chilmark pond with a periodic connection to a brackish pond and the sea.

“I remember that day,” Sheran said. “I got a big fourteen-inch brook trout in there, big hook jaw, it was like something you’d catch in a stream that you’d see in a magazine and I thought, that’s awesome. And it piqued my interest – how’d it get there and why was it there?”

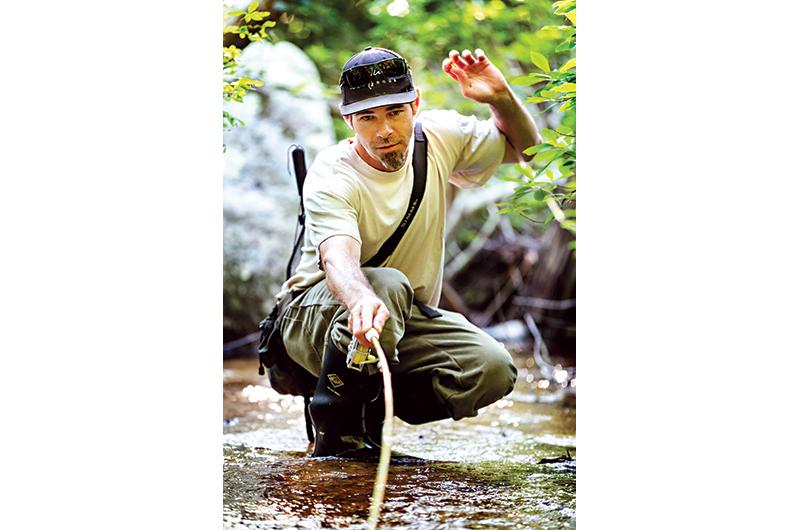

The average brook trout he finds in Island streams is generally a maximum of six inches in length. Sheran said the challenge is to visually spot the fish, get close, and present a fly without alerting it. “It’s a more tactical approach,” he said.

One encounter stands out in his mind. He was walking along a deer run, which provided a convenient path down a steep embankment on the Island’s north shore as he followed a stream that descended to the sea. He caught a few small brookies drifting a dry fly and continued to walk.

“I was looking in the pools as I worked my way down and I saw this one trout that was in a pool about two feet wide and it was actively feeding,” he said. The fish was beneath a small waterfall, seeking insects in the water flow. “He just kept coming up and rising and then sitting on the bottom,” Sheran said. “At that point there were prickers and bushes between me and him.”

He tossed a small twig into the water and watched as the trout rose, took the twig, then spit it out. He sought a way to slide down the hill through the prickers, “commando style,” to position himself for a cast. The trout took the fly on his first attempt. “It was one of the most beautiful trout I’ve ever caught here,” he said. Sheran said trout face a survival challenge in streams “chopped up” by dams and farm impoundments.

“I’ve never kept a brook trout that I’ve caught on Martha’s Vineyard. Never. I’m not opposed to harvesting fish, but in my mind the ecosystem that we have here is way too important

to ever eat one…the fish are doing what they can with what they’ve got.”

5 comments

5 comments

Comments (5)