Late one night, late in the 1960s, Albert Fischer heard the cows loudly mooing on the family farm in Chilmark. When he went to the window, he was confronted with a surrealistic tableau: the sky flooded with brilliant light.

What had stirred the cows wasn’t a harvest moon or even fireworks.

Under the sparkling umbrella of a military flare, the night was blown wide open by a unit of North Vietnamese regulars barreling through the stone walls Fischer and his father Ozzie had so carefully erected. They seemed to be advancing on the house, coming for him and his family.

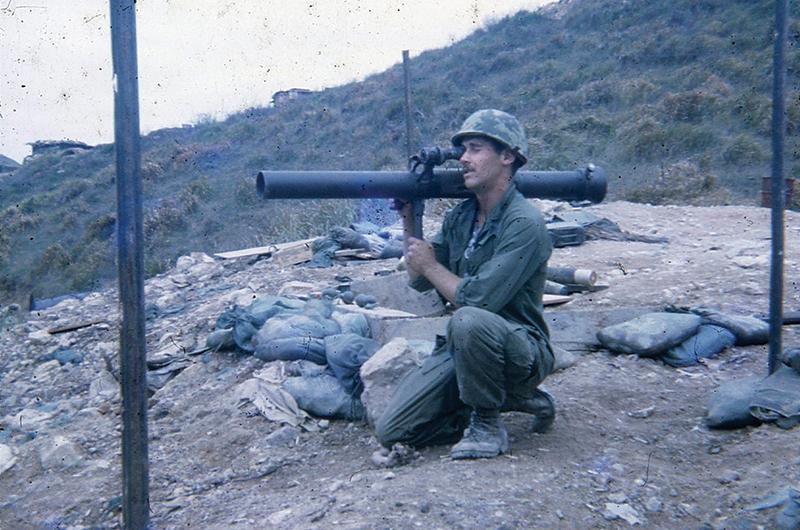

That’s how it went down – at least in his nightmares. For years after he returned from Army service in Vietnam, where he was wounded in battle, cradled one dying comrade in his arms, and saw many others fall, that assault on Beetlebung Corner was among the horrific scenes that haunted his sleep. Vietnam still lives in his memory – sometimes it is summoned, sometimes it comes on its own.

Talking about it helps, he believes, but it also tends to set off another round of painful memories – and restless nights. “I’ll dream about it tonight, [after] talking to you,” he said over coffee recently.

Fifty years ago, one of America’s bloodiest conflicts grinded away in a distant land, but it also advanced on the Island in unexpected ways, leaving behind a residue that affects the lives of Islanders even today.

In 1968 the country arguably had never been so divided since the Civil War. Early that year President Lyndon B. Johnson read the political handwriting on the wall and announced he would not run for re-election; the ensuing months saw riots in major American cities, swelling anti-war protests, and the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the era’s most significant civil rights figure, and Democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, the presumptive heir to the

Kennedy political legacy.

The Vineyard changed, too, its easy summer rituals disturbed and its families riven as they saw their finest make a fateful choice: volunteer, get drafted, or avoid military service.

Those passions of long ago have mostly subsided. But pain and loss reside just below the surface for some families whose boys lost their lives or their health or their innocence. One Islander begged off talking about a relative who died in Vietnam, saying even now: “I’m not ready to talk about it yet.”

Back then, the war over the war played out in many ways, sometimes quite publicly – on the streets, at cocktail parties, on the beaches, golf courses, and tennis courts – and sometimes quietly – in tense conversations at the dinner table, in churches, and at draft board hearings. But it was clear that by the time 1968 rolled around, the Island’s tranquil, backwater quality had already fractured over the war, as evidenced most dramatically by a bitter rift that had unfolded in the pages of the Vineyard Gazette the previous summer.

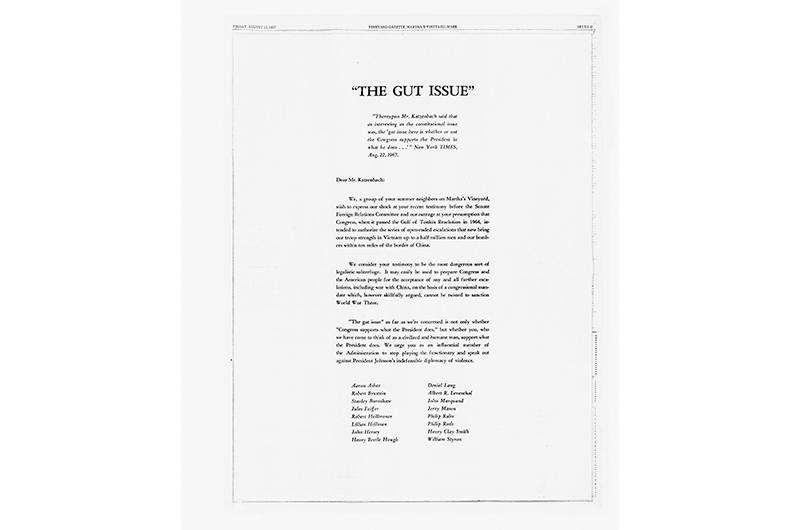

In the August 25, 1967, edition of the Gazette was a full-page ad under the headline “The Gut Issue”. It pitted sixteen signatories, including some of the most prominent literati of the day, against fellow longtime seasonal resident Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, who was then an under secretary of state in Johnson’s administration. Earlier, serving in the Justice Department, he had become a civil rights icon of sorts for helping James Meredith register as the first African-American student at the University of Mississippi, and for staring down Governor George Wallace over the integration of the University of Alabama.

Just a few days earlier, Katzenbach had testified before Congress about the legality of the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, which historians credit with enabling Johnson’s Vietnam policy and supercharging a regional conflict into what was, until Afghanistan, America’s longest war, one that would claim more than 58,000 U.S. lives. The “gut issue,” he had testified, was not whether the war was constitutional, but “whether Congress supports the President in what he does.”

The open letter included the names William Styron, Lillian Hellman, Philip Roth, Robert Brustein, and Jules Feiffer, and expressed “shock” at what they felt was Katzenbach’s call to support Johnson.“‘The gut issue’ as far as we’re concerned is not only whether ‘Congress supports what the President does,’ but whether you, who we have come to think of as a civilized and humane man, support what the President does,” the ad concluded. “We urge you as an influential member of the Administration to stop playing the functionary and speak out against President Johnson’s indefensible diplomacy of violence.”

Suddenly, the place where people retreat from mainland life and expect to be left alone was no longer a safe refuge. Katzenbach even had his house at Thumb Point on Tisbury Great Pond picketed by protesters, including Rose Styron.

Had this signaled the end of the unspoken politesse of the Vineyard? “Oh, absolutely,” Styron said recently.

It made for some strained conversation the rest of the summer, and beyond. Brustein, at that time the head of the Yale School of Drama, was buttonholed at a cocktail party by Kingman Brewster, president of Yale University, who tut-tutted him over the ad. “We leave our opinions in Woods Hole,” Brewster said, according to Brustein. “And I said, ‘What did Woods Hole do to deserve that?’”

For Rose Styron, who had been on Tom Hayden’s arm marching against the war in Washington, D.C., and Brustein, who encountered Black Panthers hell-bent on shutting down his theater in New Haven, Connecticut, this was comparatively mild stuff.

For his part, Katzenbach never responded publicly, except in a brief letter to the editor published in the Gazette in which he suggested that none of his critics had read his full testimony, and questioned “the propriety of using the accident of our common love for the Vineyard as the occasion for a personal attack upon me which in fact simply uses me as the vehicle for expressing disagreements with the administration’s policy in Vietnam.”

But the public torching was hurtful. Nearly half a century later, his son John said it still rankled. “The fact was everyone in our family, including my father, was against the war, but it was not as easy as announcing, ‘Let’s get out of Vietnam,’” he wrote in a passage in his wife Madeleine Blais’s 2017 book, To The

New Owners: A Martha’s Vineyard Memoir. He reserved a particular disdain for Brustein for singling out his father (“there were plenty of other members of the administration and numerous editorial board types vacationing on the Vineyard”), his choice of platforms (the Island’s broadsheet at the height of the summer season), and the questionable courage of his “brave stand when it was pretty damn easy to be against the war at Yale.” (John Katzenbach, through his wife, declined to comment for this story. Nicholas Katzenbach died in 2012.)

Leave it to the inimitable Art Buchwald, a summer resident and friend to some of the signatories, to put it in perspective with a generous dollop of humor. In his syndicated column, he mused whether “people have the right to ruin a man’s vacation by writing an open letter to the local newspaper on the subject that the poor official comes up to Martha’s Vineyard to forget?” One of the lessons, he added, is that Katzenbach should refuse to testify before a Senate committee during the month of August – prime time on the Vineyard.

The open letter made news in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time, and Newsweek. But on the Island? “We, the ad’s organizers, had violated basic Vineyard rules and ethics,” Feiffer wrote in his 2010 memoir. “Our act was nearly as offensive as the war itself.” Hyperbolic? Absolutely. But it spoke to how zealously some summer visitors guarded the Vineyard’s fragile bubble.

What seemed to be overlooked at the time was the name of one particular signatory: Henry Beetle Hough, who happened to be the publisher and editor of the Gazette. It was an unusual move for a newsman to take such a public stand, not on the editorial pages but in a paid political advertisement in his own paper. As Feiffer describes it, when approached about whether he would run the ad at all, Hough not only agreed but asked the group: “Would you very much mind if I added my name?”

In the same issue of the newspaper, another advertisement generated much less heat, even though it carried hundreds of names spread across a full page. It called for the U.S. to halt its bombing campaign against North Vietnam and for all parties to begin “NEGOTIATION NOW!” (The names of Hough, William and Rose Styron, and a few of the other “gut issue” signers appeared on this one, as well.)

This ad was sponsored by a group that called itself Martha’s Vineyard Summer Project, which had held lectures and petition drives throughout the season. One particularly ugly incident, at the end of the summer, marked how deep and wide the fracture had become.

On the Friday of Labor Day weekend, a group of teenagers heckled two members of the summer project who were gathering signatures on Main Street in Edgartown, according to a Gazette account. The teens also burned some of their literature and physically intimidated one of them, Woollcott Smith of West Tisbury. One of the hecklers later claimed that a police officer “had told him to go ahead and heckle as much as he wanted to, that he was going to look the other way,” Smith told the newspaper.

It turns out, the group had been refused a permit from the town selectmen to gather signatures on the sidewalk, so they got permission from landlord Alfred Hall to set up in the alcove of the vacant A&P, the Gazette reported in its September 8 issue. Hall later told the group he had mistakenly given them permission at all.

As if to signal a time-out, that same issue of the newspaper that covered the Labor Day incident contained an editor’s note on its letters page: “Correspondence as to the [Gut Issue] advertisement…is adjourned, all sides having been as adequately represented as possible.”

While at home passions had been inflamed, sides chosen, and some feelings bruised, the physical casualties of war had also taken their toll on Island families. Two Island men had lost their lives that year: Marine Corporal Daniel S. Bettencourt of Edgartown, who was killed by a grenade in May; and Army Sergeant William T. Hagerty, of Vineyard Haven, a medical corpsman with the 173rd Airborne who was mortally wounded on Hill 875 in Dak To in November.

The bloodiest year of the war was still ahead.

As January 1968 rolled around, Renee (Ortiz) Grimmett could barely contain her excitement. The newlywed was about to reunite with her husband.

She and Jon L. Grimmett had been married the previous July 1 at St. Augustine Church in Vineyard Haven, and spent less than a month together as a wedded couple before he was deployed to Vietnam with the Army’s 101st Airborne.

Renee had grown up on the Island and met Jon when she was about ten years old – it was hard not to notice him at Owen Park Beach. “He was notorious for pushing me off the end of the pier,” she said, smiling at the memory.

He was a summer kid, part of a military family that moved around a lot, but Jon’s mother was a Santos, a family with deep Island roots. When Renee and Jon began dating in 1966, she was a senior in high school and he was about to enter Army boot camp. By the end of that summer, Renee and the tall soldier with piercing blue eyes were engaged. They planned to wait a few years to get married, but in 1967 Jon learned he was headed to Vietnam, so they moved up the wedding.

A diminutive woman with long, graying hair, she beamed as she recalled the wedding. It rained the day before and the day after. But for Specialist 4 Jon L. Grimmett, in his dress uniform, and Renee Ella Ortiz, in her flowing bridal gown, July 1 dawned “sunny and bright,” she recalled. A few weeks later, he was off to Vietnam.

“I always felt that he was going to come home,” she insisted. “I never worried about it.”

In January Renee flew to Hong Kong, where Jon’s mother lived at the time – his father was a CIA officer in Vietnam – and they waited together for Jon’s leave to start. But it was not to be.

In battles that flared around the country during the run-up to the Tet Offensive, Jon’s unit came under heavy fire in Song Be, north of Saigon, and suffered heavy losses.

Jon’s commander asked him to consider staying for one more day – the very day he was supposed to start his leave. “And there was no way he was going to leave when his buddies were under fire,” said Sue Grimmett Martin, Jon’s older sister. He was shot through the chest after leading his unit, capturing two bunkers before getting hit by fire from a third. He had just turned twenty-one and been promoted to platoon sergeant. After his death, he was awarded the Silver Star, and his men nominated him for the Medal of Honor.

“I felt like I’d been shot, I’d been wounded so deeply, I was traumatized,” Renee said. “This man was the love of my life, and I felt like nobody saw my pain and I felt like nobody understood.…”

She was nineteen, angry, depressed, even suicidal. And she had come home to a different Island from the one she thought she knew. Sure, she had seen the usual intra-Island town rivalries, but this was something else entirely.

“There weren’t big demonstrations on Martha’s Vineyard, but there was tension, you could feel it,” she said. “And there was great sadness, because of loss. I just remember things being said, hearing things being said, the tension of war and people’s attitudes and the rage and attitude about Vietnam – on both sides.”

People didn’t know what to do with a young Army widow, especially one widowed by an unpopular war. “I just wanted to get the hell out of here,” Renee said. And she did. By the end of the summer, she got off the Island, and then got out of America, heading to Europe for several months.

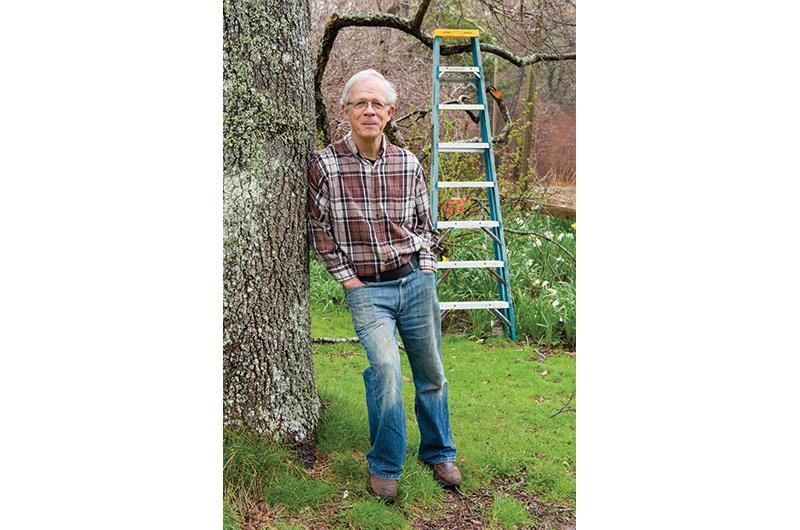

For Tom Hodgson of West Tisbury, the decision to apply for conscientious objector (C.O.) status seemed to be predetermined by his DNA. His mother was Nancy Weadock Whiting, who served as the town’s tax collector and later its librarian, a signature Island figure in the civil rights movement. She and four other Vineyard women traveled to the South and spent a night in jail after trying to help black people register to vote. Hodgson recalled being in the basement of Grace Episcopal Church in Vineyard Haven when his mother and others founded the Vineyard chapter of the NAACP – the very same day President John F. Kennedy was shot. He had, in other words, grown up in a philosophy of nonviolence, comfortable in a town that seemed proud of its tolerance.

“The community is so small, and the traditions of we-are-in-the-same-boat-together, of neighbors helping neighbors, that tolerance of opposing views and ways of life is a tradition here,” said Hodgson in his living room, just up the hill from where he grew up. “You tolerate the weird summer people, you tolerate the town drunk, you make space for everyone. The classic teaching ground for tolerance around here is town meeting. They might be calling each other names, but the next night the blues may be running and they’re fishing together.”

In 1968 the Vineyard had about 6,000 full-time residents, about one-third of its present-day population. There were about eighty-three kids who graduated from the high school that spring, the same year that more than 296,000 young Americans were drafted into the military, the second highest number of the Vietnam era. For those drafted and deemed medically and psychologically capable, the choice was to serve, go to college (college deferments ended in 1971), evade the draft, or apply for C.O. status. Nearly 600,000 men illegally evaded the draft during the era – and estimates of those who fled across the border to Canada ranged from 30,000 to 100,000. Another 170,000 were granted C.O. status – which provided a choice of service in the medical corps or two years of community service – more than double the number who sought and gained the status in World War II.

Hodgson had graduated from high school in 1966, thought briefly about going to Canada, but decided to try college – Antioch College in Ohio, where his mother and various other relatives had studied. After a year or two, however, he dropped out, immediately exposing himself to the draft. He decided to restart his bid for conscientious objector status, which he’d begun before Antioch.

By the time he appeared before the Vineyard draft board, he had compiled a two-inch file full of correspondence, letters of support, and various forms. He had studied and read to prepare for the hearing, where he expected to confront the prevailing stereotype of a draft board – a collection of saber-rattling, jingoistic sorts hell-bent on dispatching America’s finest into harm’s way. “You were taught to expect unreasoning people and hostile people,” he recalled.

Instead, what he found were a group of thoughtful Islanders who were puzzled about why he wouldn’t serve in the medical corps (in his mind it was a cog in the war machine) or just join one of the churches generally regarded as “peace churches” – Quakers, for example, with whom he had spent much of his youth and whose members frequently received C.O. status.

“I did my best to explain that it would be hypocritical to do that,” he said. “I wasn’t at a point in my spiritual life that I was ready to commit to being a member of this or that church. But my own personal beliefs were those of nonviolence…and I lived that.”

A few weeks later, sometime in 1968, the Island draft board denied his request. But in an appeal to the state board, the Vineyard decision was overturned, recognizing non-religious C.O. applications. As far as he knows, the local draft board thereafter recognized similar cases. “And this is where I give them credit,” he said. “They did not keep making the same decision. They changed. I don’t know what it was like for them, but for me it was a real affirming thing.”

His circuitous path through the Vietnam years took him back to college in early 1969, and then again into the draft pool, only to be summoned for a physical in Boston. Ultimately, he was declared 4-F – unfit for service – perhaps as the Selective Service’s way of quickly dispatching with a case rather than dealing with a potential C.O. The Vietnam era leaves him thinking aloud about an idea he acknowledged would face gale-force headwinds.

“How come we don’t have memorials to conscientious objectors?” he asked. “The general population would have a hard time wrapping their heads around such a notion.…”

Albert Fischer volunteered. As did Daniel Bettencourt. As did William Hagerty. As did Jon Grimmett. It’s noteworthy that despite the attention paid to the draft and the resistance to it, the vast majority of servicemen and women in Vietnam and elsewhere during the era were volunteers. There were a variety of reasons, among them patriotism, the chance to acquire skills, or even opportunity, especially for families that could not afford college.

By August 1969, Fischer was in Vietnam, an experience he described as boring, frenetic, gruesome, random, and surreal. He would take in a hillside with fragrant flowers on a glorious day under beautiful blue skies, only to witness one of his buddies blown up by a previously undetonated B-52 bomb. On another day, a friend was similarly killed – one who carried a Bible wherever he went, reading from it whenever he could. “That’s when I kind of lost my religion,” Fischer said.

On November 9, 1969, at midnight of the darkest of nights, mortar rounds rained down on his unit. As he reached for his helmet, he felt a blow that rattled him so profoundly he began seeing the mental images of a man whose life was about to end.

“It felt like someone had taken a Louisville Slugger baseball bat to the back of my head. I saw my parents, I saw my grandmother, waving goodbye. It was that clear.” With a piece of shrapnel lodged in the back of his head, he got medevac’d out, holding a mortally wounded private who had arrived in Vietnam too green, too scared, too young.

When Fischer came home, almost a year to the day after he went to Vietnam, he had changed. So had America. And so had the Island.

It’s a common story told over and over again by servicemen during those years. No brass bands awaiting most of them; on the contrary, they were targets for people fed up with an increasingly unpopular war. “A lot of guys, when they got to the airport, they would take off their dress uniforms,” said Tom Bennett, an Army medic who graduated from high school in 1964 and enlisted the following year.

Billy Kingsbury, a Green Beret who fought in Vietnam and Cambodia, was one of those who did not change out of his uniform before hitchhiking home to the Vineyard, stitches still in his leg from a battle wound. Somewhere en route to Woods Hole, a family slowed down to pick him up. As he grabbed the passenger door handle to hop in, the car sped away, ripping the skin off his hand. “And the kids thought it was the funniest thing, running over a soldier,” Kingsbury recalled. “So that was my welcome home.”

By the time he got home to the Island he loved, Fischer found all food tasted the same, and nothing from his previous life seemed to give him any joy. It took the love and support of friends and family to bring him back. When he headed to Menemsha, Louie Larson handed him a five-pound lobster and Curley Carroll told him to use his Boston Whaler whenever he wanted. (Carroll’s wife had sent him cookies when he was in Vietnam, and so had Julie Flanders, then just a girl.)

But there would be abrupt reminders about how the war had divided the country, and how soldiers had been stereotyped by some. He recalled a dinner party a few years later, when a summer person laid into him, calling him a “baby killer.”

“There was dead silence. You could hear forks falling on the plates. I was fearful of what I had the potential of doing to this guy. ’Cause all I could think about was my friends who died. He wasn’t insulting me – he was insulting my friends who didn’t make it.” He just got up and left.

The occasional muttered insults – or even outright confrontation about the war – would continue for years, although with less frequency. Jo Ann Murphy, now the Dukes County veterans agent, was walking down Main Street in Vineyard Haven in late 1972 when “somebody told me I should be ashamed of walking around in that uniform.” She replied: “I’m proud to be wearing this uniform.”

“America learned through us how wrong that was,” said Fischer.

At the end of the decade, a general sense of exhaustion seemed to set in – over the war, the domestic strife, and cultural upheaval. The principal of the high school, Charles A. Davis, made note of the passing decade during his annual report in December 1969.

“We have seen beards and sideburns, mini-skirts and maxi-coats, integration and segregation, hippies and yippies, assent and dissent, student activism and pacifism, drug abuse and misuse, racism and riots, ad infinitum. The list is almost endless. Their impact and impetus will remain for at least another decade.”

What he didn’t mention was the war, which would run several more years and claim another 10,000 American lives. Among them was Islander Lieutenant John R. Painter Jr., a Navy pilot who was killed flying over the Gulf of Tonkin in 1971.

Today, all around the Island there are reminders of those who served in Vietnam and came home and those who weren’t so lucky. Drive out to Franklin Street in Vineyard Haven to West Chop and you’ll see two streets on the left, in succession – first Grimmett Way and then Wm. T. Hagerty Drive. Or there are plaques, flags, or other memorials to veterans in all the towns – for example, on Main Street in front of the courthouse in Edgartown, in the Oak Grove Cemetery in Vineyard Haven, and in front of Chilmark town hall, right across from the Fischer family farm.

Fischer considers himself one of the lucky ones who had a support system to help him through rough times. An imposing but gentle man with a dry wit, he makes a point of saying he does not use his military service as a crutch – rather it seems to fortify him to remember what he endured.

“I draw my strength from it. When the chips are down, I think about what I’ve done,” he said. “A lot of times, it helps me. People say I’m a good public speaker. Sometimes I think about that when I get up to talk: ‘Look where you’ve been.’”

Renee still lives on the Island where she grew up and met Jon Grimmett as a child, became his young bride years later, and lost him soon after. She has endured love and great loss since – another marriage and divorce, and the deaths of two of her four grown children within five months of each other – Bethany, at thirty-four, just days after giving birth to twins, and Naylee, thirty-eight, after a two-year struggle with cancer. Renee nonetheless draws strength from her religion, what she describes as her spiritual connection to Jesus Christ that was forged a few years after Jon’s death.

Though their time together was short, no matter.

“It’s as fresh as though it was yesterday – in a good way,” she said. “We’re [all] spiritual beings, having about an eighty-year human experience. When I think about Jon, and I do…he’s always in my heart. Love never dies. When you die you take nothing, but you do take one thing: love.”

6 comments

6 comments

Comments (6)