It was an act of independence that was generally welcomed on the Island, which is particularly vulnerable to the challenges associated with a changing climate. “The federal government may be going in the wrong direction, but states and municipalities are stepping up,” explained Richard Andre, president of Vineyard Power, an energy cooperative dedicated to producing energy from local, renewable resources. “We live on an Island where rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and ocean acidification matter. Martha’s Vineyard already has a blue economy. It’s important we keep up the momentum at a local level.”

With 2025 only seven years away, however, there are lots of unanswered questions. How can one tiny island make an impact on a massive global issue? What does reducing the state’s carbon footprint by more than a quarter look like? Is it possible to do even more than meet the Paris Agreement goals and actually repair the environment? And the most basic question, perhaps, is how well is the island of Martha’s Vineyard doing in meeting the Paris goal of a 27 percent carbon reduction on a local level?

In order to answer the last question, one ideally would have some idea of what the Island’s footprint was in the Paris baseline year of 2005. That’s not an easy thing to do, as it turns out. “The Paris Agreement is about reducing greenhouse gases, most of which come from burning fossil fuels like oil, coal, and natural gas,” said Jeremy Houser, an ecologist at the Vineyard Conservation Society. “But there are less obvious sources of emissions too, like landfilling our garbage or our high meat consumption that are also societal choices.”

In theory, by looking at average numbers, it ought to be possible to generate a rough estimate for the Island’s footprint. The average American house has a carbon footprint of 15,000 pounds of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) per year, while the average person’s food carbon footprint – the amount of greenhouse gasses it takes to grow, process, transport, cook, and dispose of the food – ranges between 3,750 to 7,475 pounds per year, with the higher end of the range reserved for people who eat meat. The average driver in the state clocks a little more than 8,000 miles, which produces somewhere in the neighborhood of 7,000 pounds per year, plus another 1,200 pounds or so for any transcontinental flights. The ferries produce another 29 million pounds per year. You could add up the goats and sheep and cattle on the Island, and of course alpacas, and factor in the proportion of houses turned off in the winter versus those heated but empty, and the seasonal fluctuations in population, and....

You could, in other words, go cross-eyed and crazy and still not have a reliable baseline number.

It’s not hard to see signs of progress, however. From the flat farm fields of Katama to the industrial West Tisbury transfer station to a friend’s house tucked in the woods, solar arrays have been appearing more and more, like good omens. According to the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, Island-wide there are approximately 700 solar power systems in use with a capacity of roughly 13 megawatts, enough to power 2,200 homes annually.

While solar experimentation initially began on the Vineyard back in 1976 by way of the Energy Resource Group and continued under the Vineyard Energy Project into the 1990s, most of that capacity was installed in the past decade. Statewide, solar production capacity has risen a hundred-fold since 2005, from less than twenty to more than 2,000 megawatts at the end of last year.

And though the effect of Trump’s imposition of a 30 percent tariff on imported solar panels remains to be seen – a tariff, interestingly enough, that none other than Al Gore defended as “not an utter catastrophe” – the growth in solar is poised to continue. The cost of panel production is decreasing and state and federal incentives are still in place, making going solar more economical than ever. And, as most panels come with a twenty-five year warranty and pay for themselves in electricity bill savings in about ten years, solar is an easy choice for many homeowners.

“Solar will double in the next five years,” predicted Andre of Vineyard Power. “The potential on the Vineyard is very high,” echoed Marc Rosenbaum, director of engineering at South Mountain Company, a leading installer of solar capacity on the Island. “We must consider parking lots, landfills, roofs. It’s really important not to cover ancient forest and agricultural land.”

Though there is less evidence of it on the Island, thanks in part to concerns about noise pollution and view disruption, wind capacity statewide also has grown, from fewer than 15 megawatts in 2005 to more than 100 megawatts today, and the state has a goal of reaching 2,000 megawatts by 2020. Most of that growth in capacity likely will come from the large wind farms in the works for the waters southwest of the Vineyard. There are still some questions looming around offshore wind farms, both from an economic and environmental perspective. But unlike the dead-in-the-water Cape Wind plan to put turbines on Horseshoe Shoal in Nantucket Sound, the much larger projects south of the Vineyard are on track to be constructed and brought on line in the next decade. In April, the Trump administration approved the sale of another 390,000 acres of wind farm leases off the coast of Massachusetts.

“The newly slated wind farms will be barely visible, just on a clear, bright blue-sky day,” said Andre, who believes that in ten years renewable energy could account for 50 percent of our energy budget, up from the current 20 percent. Along with a group called the Vineyard Sustainable Energy Committee, he’s hoping to get a commitment from Island towns to use only renewable energy by 2040. “There is enough offshore wind capacity to power over 100 percent of the commonwealth’s demand for electricity by 2050,” he said.

The progress so far is impressive, and the predictions of continued growth in renewables are a source of optimism. For now, though, like the rest of the state, most of the Island’s electricity continues to be produced by burning natural gas. Natural gas has a far lower carbon footprint at the smokestack than the coal-fired plants they replace, and emits little in the way of other forms of air pollution. But the production of natural gas results in the release of significant amounts of methane, which is more than twenty times as potent a greenhouse gas as CO2, so the jury is out on its overall carbon footprint.

Meanwhile, the state’s efforts to import hydroelectric energy from Canada, which is essentially carbon neutral but has its own host of environmental impacts, hit a snag this past winter when New Hampshire effectively vetoed the proposed new power lines across the White Mountain region. The Baker administration is still hopeful the energy can be imported, most likely through Maine. In another environmental good-news/bad-news development, the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station, which produces roughly one-sixth of the state’s electricity and is the only major carbon-free source of electricity other than renewables, is set to stop production next May. Most sobering of all, perhaps, transportation and home heating both on the Island and across the state continue to be overwhelmingly powered by fossil fuels.

The upshot is that seven years away from the Paris Agreement deadline, we are making progress. But even going full-steam ahead on solar and wind, we are unlikely to meet the 25 percent carbon reduction target solely through increased renewable capacity.

helping second home owners to avoid wasting energy if, say, their unoccupied house has a dehumidifier running on the wrong setting.

“We’re seeing progress in the realm of sustainability,” said Richard Toole of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission. Which isn’t to say he thinks the job is done. “While building codes are improving, they could also become the same for all towns, so the process is streamlined.”

Existing homeowners can participate in free energy audits and free or heavily rebated LED bulbs and insulation upgrades from Cape Light Compact, an association of all the towns on Cape Cod and the Islands whose mission is to increase energy efficiency and offer a renewable competitive electricity supply. Lighting accounts for 9 percent of all electricity use in the country, slightly more than refrigeration and less than water heating. So it’s promising to note that in 2005, just 523 Island households used Cape Light’s services, compared with the 4,677 who signed up in 2017.

Changing light bulbs is only the beginning, however. In thinking about the more than 17,000 buildings existing on the Island right now and how, over time, each of these either will be brought into the twenty-first century or discarded and piled into dumpsters, John Abrams, CEO of South Mountain Company, suggests Islanders consider the techniques of Deep Energy Retrofitting, which often includes upgrading windows, insulation, and heating systems. “We can now rehabilitate existing buildings so they are as energy efficient, durable, comfortable, and healthy as the best of our new buildings,” he said. “Replacing a fossil fuel burner with a heat pump always reduces carbon emissions.”

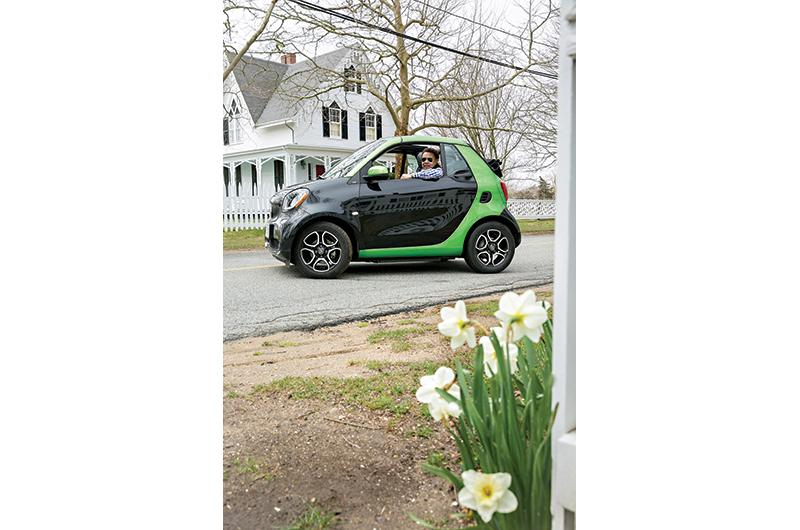

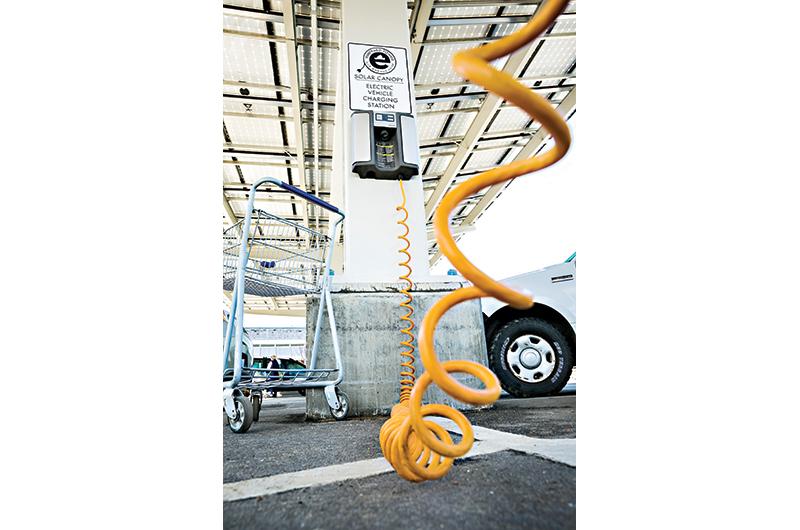

Other than natural gas (in the form of electricity from the mainland) and heating fuels, the biggest greenhouse gas contributor in the state and on the Island is transportation. While the public charging stations at Cronig’s Markets, the Oak Bluffs library, and the West Tisbury town hall are currently rarely used, there are more private electric vehicles on the road every year and most major manufacturers have more electric models – think small SUVs, trucks, and minivans – in the pipeline that promise to be more pleasing in terms of price, driving range, and availability. The number of plug-in electric vehicles sold annually in the United States has increased eight-fold since 2011, to around 150,000 a year. West Tisbury and Oak Bluffs, meanwhile, have acquired hybrid and electric vehicles for town use, and the Vineyard Transit Authority has a plan to convert to 100 percent solar electric as the current vehicles age out. Statewide, the goal is to have 300,000 electric cars on the road by 2025, and legislation was passed last year to speed up the installation of charging stations.

While the transportation sector may be lagging in the race to decrease climate impact, waste management is an area where the Vineyard is making progress, and in some cases leading the way. Though not as obvious a source of carbon in the atmosphere as, say, the tailpipe of an SUV, reducing waste can have a large impact on climate change. It’s not just the fuel used hauling the stuff to the dump, though 15 percent of the truck traffic on Vineyard ferries is doing just that. Along with agriculture and petroleum production, solid waste landfills are a leading source of the potent greenhouse gas methane. Last but not least: anything that is thrown away is something that has to be made again, using energy and emitting greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere.

The effort to reduce waste on the Island largely has been lead by the nonprofit sector. Last year the Vineyard Conservation Society successfully campaigned to have single-use plastic bags banned Island-wide. Sail Martha’s Vineyard, which is best known for its low-cost sailing programs for Island youth, but which also considers advocating for the health of oceans an integral part of its mission, has developed a model for zero-waste event planning that has been adopted by Hospice of Martha’s Vineyard, the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, and numerous sailing regattas off-Island.

Island Grown Initiative, meanwhile, has developed a network to reduce food waste and compost what remains. Residents who don’t want to compost at home can now bring their own household food waste to the Edgartown, West Tisbury, and Chilmark refuse centers. Additionally, “any restaurant or businesses can set up an agreement with a farmer to pick up their food scraps, or they can call Island Grown Initiative to set up the service,” said Sophie Mazza, director of food equity and recovery at the nonprofit.

There is still much work to be done: the Island has not yet followed France’s complete ban on single-use plastics. “Everything comes in stages,” said Kimberly Ulmer, director of sustainability for Sail Martha’s Vineyard. “Hopefully polystyrene and balloons can be next.”

In particular, say most local advocates, there has not been a serious commitment at the town level. “Buildings are being designed, such as the Tisbury School and the Oak Bluffs town hall, that are unlikely to achieve what’s possible because the commitment does not appear to be there,” said Abrams, whose company is working with the nonprofit Martha’s Vineyard Community Services to develop a “net-zero” campus.

“We have been slow,” echoed Andre regarding town governments. “We need a grassroots movement here with more leadership at the town level to take the 100 percent renewable pledge and/or become a green community.”

Since the passage of the state’s Green Communities Act in 2008, of the 351 municipalities across Massachusetts, 210 have signed on to move toward renewables and conservation-oriented building codes. On the Island, however, only West Tisbury and Tisbury are participating. And despite a laudable turnout of state representatives, experts, and local business and nonprofit leaders at the Renewable Energy Summit last fall at the Oak Bluffs library, few town officials were present.

“Planning boards, more people should be hearing this,” said Toole, who attended the summit and wears at least half a dozen volunteer’s hats in the Island energy world. “Oak Bluffs has an energy committee of one [himself]. No one else wants to put in the time; that’s what it takes.

“The time is now, the ball is in our court,” Toole said of meeting the goals of Paris. “The ordinary person can do more than they think.”