One of Lee’s best sources on all things cranberry was Craig Kingsbury, a larger-than-life Islander who died in 2002. Kingsbury’s eclectic résumé included not only time spent working the cranberry harvests, but a stint preparing actor Robert Shaw for his role in Jaws – to show him, as Kingsbury put it, how to behave like “a fish-pier low life, a filthy wharf rat.” When Kingsbury was a young man, he reported, cranberries were growing all over. He said he always preferred the wild ones:

“Go out there and get some of the wild berries,” he told Lee, “’cause I think they’re better. They were very dark, almost black. Smaller, but I thought they were better. I’d pick a bushel, stuff for the winter. Lot of people did that. Went picking on the wild bog. Don’t go in the private bog! Get your arse kicked. And there was a rap then on, probably isn’t now, anyway, about picking bogs was considered the same as trespassing. And breaking and entering. Picking bogs for fruit, berries, anything like that. You could [get] a fine up to 100 bucks for it, if they caught you.”

That was a considerable sum at a time when pickers were paid fifty cents a bushel, something Kingsbury knew from personal experience. “Down on your hands and knees in the goddamned muck and still the mosquitoes and the flies are out to keep away a dull time. No, it was not fun.”

Until the invention of a stand-up harvester in 1947, virtually all picking was done, as Kingsbury described, by crouching over the low-lying bushes. Other than the introduction of wooden scoops in the late nineteenth century, the back-straining work was little changed from that undertaken annually by generations of Wampanoags and members of other New England tribes. Since long before anyone can remember, native New Englanders picked in the natural depressions, particularly the kettle ponds, carved by the ice age and filled in with silt. Spongy patches of sand and soil with poor drainage, enriched by years of plant decay and mineral deposits, are ideal growing grounds for cranberries. The Wampanoags established traditions of caring for the Island’s acres of “wild” bogs to ensure a plentiful supply of vitamin C–filled fruit for their winter diets. They used the berries to make dyes and medicine, and dried some and pounded them with venison to make pemmican, a kind of jerky hunters and fishermen carried with them. The remainder they ate “fresh” through the cold season (cranberries, like apples, will last for weeks or even months). They enjoyed them raw – they didn’t mind the tartness – and cooked them, sometimes with cornmeal, other times with meat.

The Pilgrims and other seventeenth-century immigrants appreciated the nutritional value of cranberries, but often found the sourness hard to take. The arrival of honeybees in the colonies and the expanding West Indian sugar trade helped. Once cranberries could be sweetened, eating them became more popular. In 1672 John Josselyn, an English visitor to New England, became the first to mention cranberries in print, noting that “the Indians and English use them much, boiling them with sugar for sauce to eat with their meat. And it is a delicate sauce, especially for roasted mutton. Some make tarts with them as with goose berries.” A hundred years later, when Amelia Simmons published the first cookbook in America (American Cookery, 1796), she featured a recipe for a cranberry tart. She directed that the fruit be “Stewed, strained and sweetened, put into paste No. 9, and baked gently.” She also advised that roast turkey was nice served with “boiled onions and cramberry-sauce [sic], mangoes, pickles or celery.” By that time cranberries were eaten widely on the Island and were regularly taken on whalers and other ships to fight scurvy.

Commercial cultivation began on Cape Cod in the early 1800s and spread to Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Production on the Island peaked in the early decades of the twentieth century before taking a series of hits. The great Hurricane of 1938 damaged the bogs, demand decreased during World War II, labor became scarce, canned sauce grew popular, and other wintertime sources of vitamin C became increasingly available. With the introduction of mechanical harvesting and greater commercial use of pesticides, the Cape’s cranberry industry eventually rebounded. But the Vineyard’s never recovered. The patchwork of smaller bogs scattered around the Island made it prohibitively expensive to transition to new methods, and one by one the commercial bogs were put to other uses. When the last one, on Lambert’s Cove Road, became the Cranberry Acres campground in the 1970s it was clear an era had ended. Commercial cranberry farming disappeared, then private growing followed suit. Come Thanksgiving, unless an old timer pointed you to a wild patch, you had to buy fruit grown on the Cape or trucked in from the Midwest.

For a time, only members of the Tribe in Aquinnah continued to harvest and honor the cranberry on Martha’s Vineyard; Cranberry Day remains an excusable school absence for Wampanoag kids. Mindful of the historic importance of the fruit, Aquinnah families celebrate the harvest from wild bogs on tribal lands. Most others, though, seemed little concerned about the disappearance of a major crop and culinary mainstay.

Luckily, a few people were paying attention. Carol Magee, for one, has been thinking about the importance of bogs and cranberries for a long time. Magee is the executive director of the Vineyard Open Land Foundation (VOLF), a nonprofit established in 1970 to “promote the preservation of the natural beauty and rural character of Martha’s Vineyard.” In 1981 VOLF organized the purchase of the forty-five-acre Cranberry Acres campground parcel; it eventually sold seven carefully located building sites and preserved the remaining twenty-three acres with an eye toward the renewal of the original six acres of cranberry bog and three reservoir ponds.

It’s been a slow process. So far VOLF has restored half an acre of the old bog and has cleared an additional two for future restoration. Magee and her organization are committed to growing and harvesting in the traditional manner without the use of pesticides or heavy equipment, and to bringing certified organic cranberries to market. There was much to learn initially, but over time, with the help of an organic grower from the Cape, VOLF is figuring things out. It improved the irrigation channels, weeded carefully, and now regularly does a late-water flood in the spring to protect the young plants from blackheaded fireworms. (VOLF harvests in a dry bog; in fact, all cranberries sold fresh are dry harvested – only berries destined for juice or sauce are gathered in flooded bogs.)

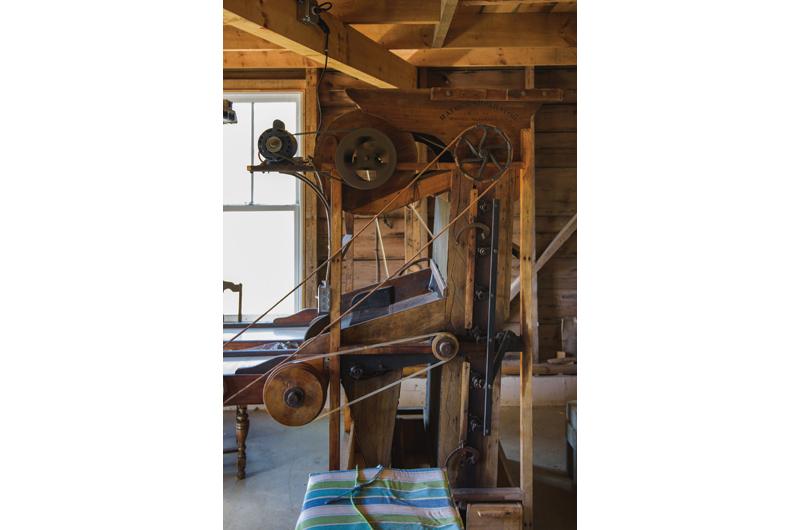

Last year VOLF sorted more than 2,000 pounds of fruit using historic machinery in its cranberry shed on Lambert’s Cove Road. The berries are all sold on-Island, usually beginning in October, at about $10 a pound. While some might balk at the price, strong sales indicate that many see the value of toxin-free, great-tasting berries grown as part of rebuilding a connection to an Island agricultural tradition. Here’s hoping it won’t be too long before folks are inspired to give the Island’s overgrown (or mowed) private bogs some renewed love and attention.

The following recipes were originally published along with this article:

Chicken Braised with Walnuts and Cranberries

Cranberry Tart with Walnut Streusel

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)