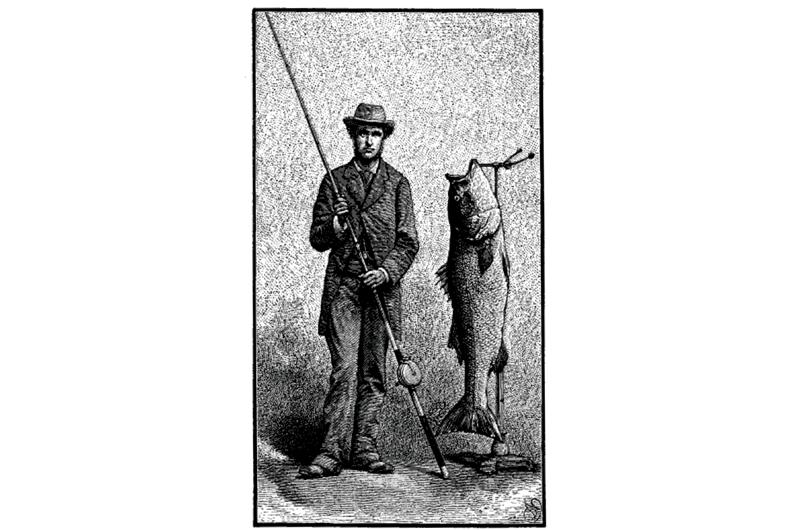

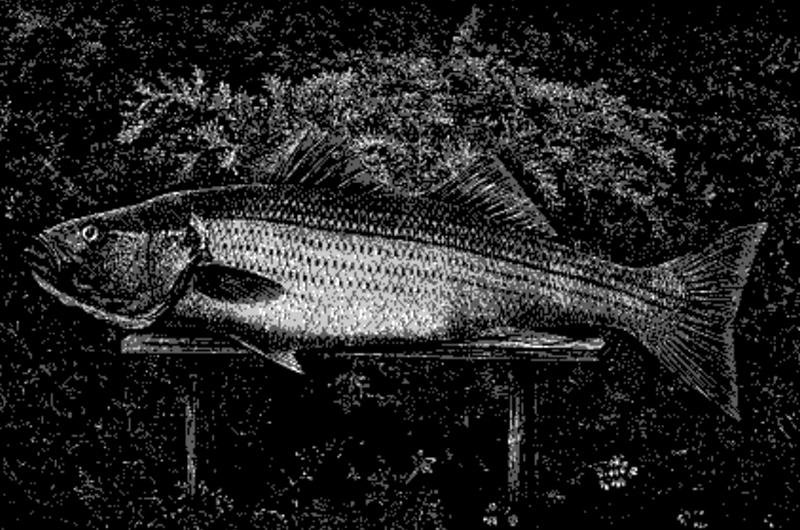

To the lover of rod and reel, the striped bass, or rock-fish, as he is called south of Philadelphia, is the most important of all our sea fish. His habitat is so extended and his stay with us so constant; he is so eagerly sought for by anglers of all classes and conditions of life; he affords such sport in the various stages of his growth, from the puny half-pounder found almost everywhere on our Atlantic coast, to the enormous “greenhead” who makes his home in the break of the surf; he brings into play such a variety of tackle, from the pin-hook of the urchin fishing from the city docks to the jewel-mounted rods and reels of the crack bass-fisherman, – that he well merits the title which is sometimes bestowed on him of the game fish par excellence of the sea – the fish for the million and the millionaire.

A bright August morning found the writer, in company with a member of the Cuttyhunk Club, steaming down the bay from New Bedford, bound for a trip to the Elizabeth Islands and Martha’s Vineyard, and for a bout with the large bass which frequent the rocky shores of those favored regions.

Arriving at the mouth of the harbor, as our little craft steams around Clark’s Point and enters Buzzards Bay, the whole range of the Elizabeth Islands comes into full view, and we find ourselves trying to repeat the old verse by which our ancestors remembered their uncouth Indian names:

“Naushon, Nonamesset,

Uncatena and Wepecket,

Nashawena, Pasquinese,

Cuttyhunk and Penikese.”

There is a mysterious influence at work in these regions which seems to gather the sea fogs and hold them suspended around the islands, shutting them in completely, while all about the atmosphere is clear. As we approach the land we observe this phenomenon and are soon lost in its dense vapors. We steam along slowly, our fog whistle shrieking at intervals, and every eye strained forward for rocks or vessels which may be in the way, until presently we hear a distant fog horn answering us, and following it we find ourselves among a fleet of swordfishermen anchored for the night in Cuttyhunk Bay....

On the following morning we leave our hospitable friends, our destination being Gay Head. We can see its many-colored cliffs from the clubhouse, across the Vineyard Sound, only eight miles away; but the wind is contrary and the water too rough for the small boat at our disposal, so we conclude to return to New Bedford by the more tranquil waters of Buzzards Bay, and take the steamer thence to Martha’s Vineyard....Emerging from [Woods] Hole into the Vineyard Sound, we steam away for the headlands of Martha’s Vineyard, visible in the distance, and in due time haul up at the wharf of that marvelous city of cottages, and take the stage to commence a tedious journey the full length of the Island, some twenty-two miles.

As the stage route does not extend beyond Chilmark, we are transferred at Tisbury to a buggy, with a bright school-boy of some thirteen summers as a driver, whom we ply with questions as to the names of localities passed on the route, and when he gives some particularly uncouth Indian name, we drop down on him suddenly and drive him to the verge of despair by asking him to spell it. “That,” says our young Jehu, pointing with his whip, “is Quabsquie Cliff.”

We hold the pencil suspended for a moment, as though in doubt as to a letter.

“How do you spell it?”

“Q-u” he starts off bravely, but breaks down at the third letter. “I don’t know – I never saw it in print.” “Well, spell it as it is pronounced.” “Q-u-o – no, a-b-s-k – no, q-u-i-e.” And so we go on to the next, when the same process is repeated.

We cross some noble trout streams on the way; on one of them notices are posted against trespassers, the fishing privilege being hired by two or three gentlemen from Boston. These streams look enticing, being full of deep holes overshadowed by scrubby alders – the lurking-place of many a large trout, if we may believe our young guide. The trout should be full of game and fine-flavored in these streams – pink-fleshed, vigorous fellows, such as we find in the tidewater creeks of Long Island and Cape Cod, who take the fly with a rush that sends the heart jumping into the throat.

It is dark when we reach Gay Head, and as we drive up to the door of the keeper’s house, which adjoins the lighthouse, a voice from some unknown region cheerily invites us to enter. We look around for the owner, but see no one to whom the voice could belong. Overhead, long, slanting bars of white-and-red light flash through the powerful Fresnel lenses in every direction, looking like bands of bright ribbon, cut bias against the darkness of the sky beyond, while millions of insects dance in the broad rays, holding high carnival in the almost midday glare. The mysterious voice repeats the invitation, and without more ado we gather our baggage together and enter a cozy sitting room, where we proceed to make ourselves very much at home. Here we find Mr. Pease, the keeper of the light, who has descended from his lantern since he accosted us outside, and a gentleman from New Bedford, who gives but poor encouragement in regard to the fishing. He has been here for a week past, and has not caught a solitary bass in all that time; but he tells us such soul-stirring yarns of fish caught on previous visits, and all told with a modesty which attests their truth, that our spirits are restored at once....

The cliffs at Gay Head are interesting alike to the artist and the geologist, and possess still another interest for the angler, who has to carry fifty pounds of striped bass up their steep and slippery incline. They are of clay formation, broken and striated by the washings of centuries, and when lighted up by the sun present a brilliantly variegated appearance, which undoubtedly gave the promontory its name. Black, red, yellow, blue, and white are the colors represented, all strongly defined, and on a clear day discernible at a great distance. Down their steep sides, our feet sticking and sliding in the clay, moist with tricklings of hidden springs, we pick our way slowly, bearing our rod and gaff-hook, while our little Indian staggers under a basket load of chicken-lobsters, purchased of the neighboring fishermen at the extravagant rate of one dollar and fifty cents per hundred.

At the bottom of the cliffs we skirt along the beach, stopping now and then to pick up bunches of Irish moss, with which the shore is plentifully lined, until we come to three or four large granite bowlders lying at the edge of the water, and offering such attractions as a resting-place, that we stop and survey the field to select our fishing-ground.

Across the Vineyard Sound, about eight miles away, and stretching out far to the eastward, are Cuttyhunk, Nashawena, and Pasque islands, and about the same distance to the southwestward the little island of Noman’s Land is plainly visible in the clear atmosphere – even to the fishermen’s huts with which it is studded. It is a notable place for large bass, and wonderful stories are told of the catches made there – how, on one occasion, when the fish were in a particularly good humor, three rods caught twelve-hundred-and-seventy-five pounds of striped bass in a day and a half. Only a short time since, Mr. Butler, who lives on the island, caught and sent to New Bedford a striped bass weighing sixty-four pounds.

Looking out seaward some thirty or forty yards, we see three rocks heavily fringed with seaweed, which rises and spreads out like tentacles with the swell of the incoming tide, and clings to the parent rocks like a wet bathing dress as the water recedes and leaves them bare. We like the appearance of this spot – it looks as though it might be the prowling-ground of large fish; and we adjust our tackle rapidly and commence the assault.

Into the triangle formed by these rocks we cast our bait again and again, while our attendant crushes the bodies and claws of the lobsters into a pulp beneath his heel, and throws handfuls of the mess out as far as his strength will allow. He appears to have inherited some of the taciturnity of his ancestors, for not a superfluous word do we get out of him all day long; all efforts to lead him into conversation are met by monosyllabic answers, so that after many discouraging attempts, we imitate his reticence and are surprised to find with how few words we can get along. A nod of the head toward the sea brings him into immediate action, and he commences to throw out chum vigorously, like a skillfully made automaton; a nod of another significance, and he brings three or four fresh baits and deposits them silently at the rock at our feet.

Thus we fish faithfully all the morning, buoyed up by the hope which “springs eternal” in the breast of the angler, but without other encouragement of any kind. Many nibblers visit our bait and pick it into shreds, requiring constant attention to keep the hook covered, while rock-crabs cling to it viciously as we reel in, and drop off just as we are about to lay violent hands on them.

The flood-tide, which had commenced to make when we arrived, is now running fast, and has risen so as to cover the rocks on our fishing-ground, leaving nothing visible but dark masses of seaweed floated to the surface by its air cells, and waving mysteriously to and fro. The surf has risen with the tide, the water is somewhat turbid and filled with small floating particles of kelp or sea-salad, which attach themselves to the line and cause it to look, when straightened out, like a miniature clothesline. Occasionally a wave will dash up against the shelving rock on which we stand and, breaking into fine spray, sprinkle us liberally, and as salt water dries but slowly, we are gradually but nonetheless surely drenched to the skin.

Suddenly, without the slightest indication of the presence of game-fish, our line straightens out, we strike quick and hard to fix the hook well in, the reel revolves with fearful rapidity and the taut line cuts through the waves like a knife, as a large bass dashes away in his first mad run, fear and rage lending him a strength apparently much beyond his weight. Of course, under the circumstances, the strain on the fish is graduated, but the weight of line alone which he has to draw through the water would be sufficient to exhaust even a fifty-pounder, and he soon tires sufficiently to enable us to turn his head toward land. As we pilot him nearer to the shore, he acts like a wayward child, making for every rock which happens in the way, and as there are many of them it requires no little care to guide him past the danger; presently, however, the steady strain tells on him, his struggles grow weaker, his efforts to escape become convulsive and aimless, and we lead him into the undertow, where he rests for a moment, until a wave catches him and rolls him up, apparently dead, on the shelving sand. As he lies stranded by the receding water, the hook, which has worked loose in his lip, springs back to our feet. Our little Indian sees the danger and rushes forward to gaff him...but we push him aside hurriedly – no steel shall mar the round and perfect beauty of the glittering sides – and rushing down upon him, regardless of the wetting, we thrust a hand into the fish’s mouth and thus bear him safely from the returning waves; then we sit down on the rock for a minute, breathless with the exertion, our prize lying gasping at our feet, our nerves still quivering with excitement, but filled with such a glow of exulting pride as we verily believe no one but the successful angler ever experiences, and he only in the first flush of his hard-won victory.

But there is no time to gloat over our prey – bass must be taken while they are in the humor, and our chummer is already in the field, throwing out large handfuls of the uninviting-looking mixture; so we adjust a fresh bait and commence casting again, as though nothing had happened to disturb our serenity, only once in a while allowing our eyes to wander to the little hillock of seaweed and moss under which our twenty-five pound beauty lies sheltered from the sun and wind.

Another strike, another game struggle, and we land a mere minnow of fifteen pounds. And this is all that we catch; the succeeding two hours fail to bring us any encouragement, so we reel in, and painfully make our way up the cliffs, bearing our prizes with us.

We are eager for another day at the bass, but a difficulty presents itself: fish are perishable in warm weather, the bass in a less degree than many others, but still perishable, and we have no ice, nor is any to be purchased nearer than Vineyard Haven – which for our purpose might as well be in the Arctic regions. But we bethink us that we have friends at the Squibnocket Club, some five or six miles away, on the southwest corner of the island, and in the afternoon we persuade Mr. Pease to drive us over there.

The comfortable little club-house is built facing and adjacent to the water, and after supper, as we sit chatting over a cigar on the piazza, we look out upon the wildest water we have as yet seen. The shore is exposed to the direct action of the ocean, without any intervening land to break the force of the sea, and the white breakers follow each other in rapid succession, lashing themselves against the rocks into a foamy suds, which looks as though it might be the chosen home of large bass – as, indeed, they say it is. Over this broken water some half-dozen of the club-stands are erected, in full view of the house. And although the sun has gone down, two or three enthusiastic anglers are still at their posts, trying to add to their score for the day.

The following day is almost a repetition of the first – a long, profitless morning spent in fruitless casting, a sudden strike when we least expect it, and the catching of three fish within an hour and a half. This capricious habit of the bass is very striking at times. Sometimes, day after day, they will bite at a certain hour and no other time. Whether it is that they have set times to visit different localities, and only arrive at the fishing-ground at the appointed hour, or, whether they are there all the time and only come to their appetites as the sun indicates lunchtime, we cannot say.

Our trip is over, and we pack our things to return home. Stored in a box, carefully packed with broken ice, are five bass, – we take no account of two bluefish of eight and ten pounds, – which weigh respectively twenty-five, fifteen, twenty-eight, twenty-one, ten pounds. This constitutes our score for two days’ fishing at Gay Head.

(We felt the value of this historical piece outweighed its occasionally insensitive language – MVM.)

This excerpt was originally published with the article The Old Squibnocket Club.