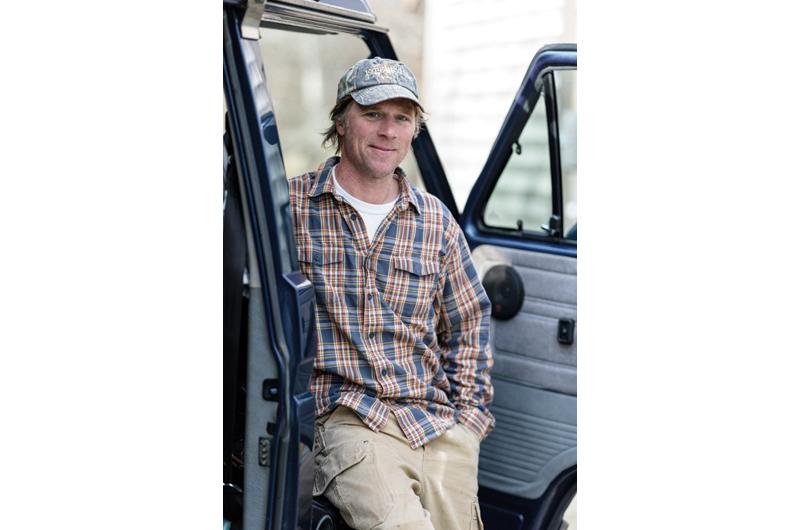

In the morning, when Nick Bologna walks down the stairs of his Aquinnah home, his joints crunch like snapping twigs. Swollen knees and ankles crack as he makes his way to the hot tub, which is not a mere indulgence. Bologna has lived with chronic Lyme disease for more than twenty years and a pre-work soak in very hot water has proven to be one of the most effective pain and tension relievers.

Sometime in the early 1990s, Bologna came down with a high fever accompanied by a red, bruised-looking tick bite. Today, he would likely immediately be treated with the antibiotic doxycycline in an effort to halt the spread of the Lyme bacterium. But, at the time, there wasn’t a lot of awareness around the shadowy disease. “I never even suspected it; I just thought I had a summer flu or some sort of bug,” he said.

Bologna was working as a builder, spending much of his day outdoors and finding embedded ticks on himself at least once a week. Without that early antibiotic treatment, the disease spread throughout his body. And while the intensity of Bologna’s symptoms occasionally subside, they always return.

“I still wake up most mornings with my arms, hands, and legs numb and tingling from the inflammation,” he said. For two decades, fatigue has been Bologna’s most crippling symptom. “It’s at a point where I feel like I could fall asleep at any point in the day if I had the time to do so.” But with a wife, two young children, and a physically demanding job, time to snooze is not something he has in excess.

As Bologna and others know all too well, tick-borne disease is nothing new on the Vineyard. As far back as the 1920s there were organized efforts to control ticks on the Island, though the concern at that time was more for the comfort of pet dogs than to combat serious diseases. In the mid-1970s, local cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, and babesiosis made the pages of the Vineyard Gazette. Tellingly, a 1979 article in the Gazette about a Massachusetts Department of Public Health report on tick-borne diseases did not mention Lyme. The study tested some fifty people on the Cape and Islands who had such symptoms as a spreading rash and fever, and confirmed only four cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. What the other forty-odd patients had is unknown, but in hindsight Lyme disease, which had been isolated and named after the town of Lyme, Connecticut, only two years earlier, seems an obvious candidate.

Now, four decades later, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health lists Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket as having among the highest incidence of tick-borne disease in the state. On any given summer day, Dr. Gerald Yukevich of Vineyard Medical Care might treat upward of sixty patients in his Vineyard Haven clinic. Of those, eight or nine will be cases of Lyme disease, or perhaps another tick-borne disease, such as anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, or tularemia. “There is just an awful lot of it in the summer,” he said. “We are vigilant, and very cautious.”

By cautious, he means that he will likely treat any combination of Lyme-typical symptoms, such as swollen lymph nodes, fever, headache, or stiffness of the neck, with doxycycline, whether or not the patient has the telltale bullseye rash. Better safe than sorry, in other words. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), untreated Lyme can lead to an array of symptoms, including facial palsy, swelling of the brain, and short-term memory loss. “It’s truly a public health problem,” said Dr. Yukevich. “Everyone on this island is at risk.”

But while virtually everyone agrees something should be done, not surprisingly the agreement stops there. Some say preventing Lyme disease is as easy as putting your clothes in the dryer for five minutes on high heat to kill any ticks that followed you inside. Others say it’s time to significantly cull, or even exterminate, the burgeoning deer herd. There’s even a plan afoot to develop and release genetically modified mice in an attempt to stop the disease cycle before it spreads.

Ticks are not insects but crawling arachnids, and are closely related to spiders. They have four life stages (eggs, larva, nymph, adult) before they can lay eggs and release another generation of blood-sucking spawn into our backyards. Once hatched, a tick must feed on the blood of a new and preferably different host in order to move to the next phase. The three known species on the Island – black-legged “deer” tick, dog (or “wood”) tick, and the newcomer lone star tick – are not particularly discriminatory creatures in the earlier stages, feeding on mammals, birds, and reptiles. When they reach adulthood, however, they become more finicky and look to feed solely on larger mammals, preferably white-tailed deer in the case of black-legged ticks, which are the primary vectors of Lyme disease on the Island. Deer, that is, or dogs and humans.

The whole process can take between two and three years. But if, for any reason, a tick fails to find a host at any stage of its life, it will die without ever having the chance to reproduce. What’s more, ticks are not born with tick-borne illnesses, so if a tick fails to feed off a previously infected host before reaching a human host, it will not carry the disease. As a result, most efforts at controlling tick-borne illness involve breaking either the life- or the disease-transmission cycle at one stage or another.

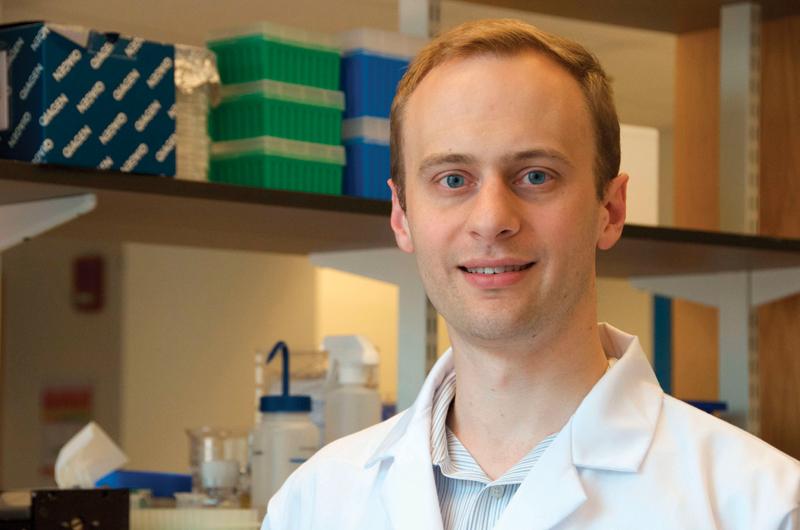

Biologist Kevin Esvelt thinks the weak link may be mice. Mice are hospitable hosts to ticks and a primary vector of Lyme disease. They get the disease when bitten by an infected tick, and also transmit the disease when an uninfected tick bites previously infected mouse. Esvelt believes that if mice can’t contract Lyme, far fewer deer and humans will either. From his single-windowed office at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Esvelt pointed to an unassuming building across a tree-lined walkway. Inside, scientists and technicians are encoding the genome of hundreds – and eventually hundreds of thousands – of mice for Esvelt’s proposal to introduce genetically modified mice to the wild in an attempt to curtail the spread of Lyme disease.

For someone in such a cerebral line of work, he gives a surprisingly emotional reason for tackling tick-borne disease: his two young children. “The essence of childhood is to run through the woods without a care and in some places that’s just not a safe thing to do.”

Esvelt’s proposal begins with engineering mice that are either resistant to Lyme disease or resistant to tick bites. Those mice will be released on an as-of-yet-undetermined uninhabited island for observation. Finally, barring any major surprises or community resistance, the super mice could be set loose on the Vineyard and elsewhere. From there, scientifically tweaked nature will run its course.

Esvelt’s lab at MIT is a leader in gene drive technology research, a new approach to genetic engineering that results in an organism’s offspring inheriting most or all of inserted genes at a higher rate than a naturally selected mutation. Gene drive causes the modified trait to spread quickly throughout an entire population, and is controversial because it has the potential to permanently and irreversibly alter the entire natural population of a species. Esvelt’s current proposal differs from this approach in that it is localized, and therefore ultimately reversible. The mice will be modified individually and released by the hundreds of thousands in hopes of overwhelming the local population.

While the proposal is innovative, Esvelt’s approach to selling the idea is downright radical. He is encouraging community involvement and transparency that is unprecedented in his field. Last summer he hosted a forum at the Edgartown library, and met with community members on Nantucket, where he is also shopping the idea. “I wanted some die-hard critics,” he said. “I want to open it up to the public, not just scientists. We need as many people looking at this as possible to find what could go wrong and address it.”

The actual release of mice is years away, if ever, but Esvelt is buoyed by the support he’s received so far. “We’ll have thousands of engineered mice by 2020,” Esvelt said. “Then we’ll let them do their thing for a few years on an uninhabited island. There is a lot of time to talk about this.”

Jeremy Houser, a behavioral ecologist with the Vineyard Conservation Society, is both excited and concerned about the proposal. He attended the presentation in Edgartown and doesn’t question Esvelt’s ethics. Nor is he categorically opposed to genetic manipulation: “It’s a mistake to think that today’s genomes are perfect – evolution isn’t planned, or intelligently designed,” he said in an email, “however, the default expectation is that if we humans alter the genome of another organism to better suit our purposes, the effect on that organism will be negative.”

But Houser doubts genetically modified non–gene drive mice will ever overwhelm the natural population, and that in order to have a lasting effect on the incidence of tick-borne illnesses, the mice will have to be added to the natural population continuously. “The problem is that, in my opinion, it’s just totally unrealistic,” he said, “requiring an astronomical commitment of time and money.”

Unless, of course, the community ultimately considers releasing gene drive mice once they are convinced that the Lyme-resistant mice actually reduce disease without unacceptable side effects. On an Island that spends decades deciphering the relative moral implications of traffic lights versus roundabouts, one can only imagine the debate.

“This is not an insect,” said Houser’s colleague Brendan O’Neill, the executive director of the Vineyard Conservation Society. “This is a mammal – a complex organism and the technology is moving very, very fast. There is a whole world of unintended consequences, not to mention regulatory problems.”

Even some who see promise in Esvelt’s proposal worry about its trajectory, because what the genetically modified–mice project has in vision, it lacks in immediacy. “It’s good that they’re doing it,” Island biologist Dick Johnson said of Esvelt’s work, “but we can’t afford to put anything else on hold. We need to drop the deer population. I think it’s our best chance.”

Johnson, who works with the tick-borne-illness prevention program that is sponsored by the boards of health of the six Island towns, is not diametrically opposed to the introduction of genetically modified mice on the Island as part of a strategy to combat tick-borne illnesses. But he is a firm believer that the place to break the cycle is not with mice but deer. Fewer deer means less Lyme, and that is where efforts should be focused.

Johnson is a proponent of an organized effort to cull the Island’s massive herd of deer, which some estimates put at around 3,000 to 5,000 animals. Specifically, he wants more people to allow hunting on their property. He also advocates expanding the current season and granting waivers to hunt closer than 500 feet from residences. All six Island boards of selectmen agreed to send letters to the state Division of Fisheries & Wildlife in support of culling the deer herd. Culling the herd is a cost-effective solution, he said, that would produce immediate results.

But while fewer deer would almost certainly ease problems associated with overpopulation, including dangerous vehicular encounters and garden nuisances, it is less clear what that will mean for the tick population and the spread of disease. Kiersten Kugeler is an epidemiologist with the CDC whose research focuses on Lyme disease prevention. In a study published last year, she and her colleagues specifically explored the question of whether culling white-tailed deer will curtail Lyme disease. In their findings they outlined three levels of prevention: individual actions like repellents and tick checks, household actions like landscaping, and community actions, of which reducing the deer population was a prime example.

“Effective community-level interventions hold promise,” they wrote, “because of their potential to provide a broader spatial effect without reliance on individual human behavior to achieve success.” But despite that general endorsement, the team concluded that there is not enough evidence to recommend deer population reduction as a prevention measure, except in specific ecologic circumstances.

“Unless a community’s herd can be culled almost to elimination, the effect on the spread of disease is minimal,” she said, when reached by telephone. And in most ecological circumstances, culling deer to that extent would be impossible – though not necessarily on an island.

Cull supporters, on the other hand, like to point to Monhegan Island in Maine where, between 1996 and 1999, a group of professional hunters was hired to eliminate that island’s deer population. Afterward, the tick population plummeted, and Lyme disease was apparently eradicated.

Over the course of ten years before enlisting sharpshooters, Monhegan Island experimented with several other programs aimed at reducing the tick population, from setting guinea hens loose to treating rats and deer with a tick-killing compound. Yet until island residents finally voted for a deer cull, they didn’t see any change in tick population or tick-borne disease.

Charles Lubelczyk, a wildlife biologist with the Maine Medical Center Research Institute, worked as a field tech over the two-year course of the cull. “Culls work in island communities,” he said. “The problem is that it’s a very democratic process and it can get contentious.” He said that genetic research like Esvelt’s is “pretty sexy science” and worth exploring, though not at the expense of ignoring existing technologies.

Today, there are no deer on Monhegan and the small population of ticks that remain feed on rats. Still, the tick population is so low that it’s on par with nearby Matinicus Island, which has never been home to deer.

For his part, Johnson doesn’t think that deer have to be completely eliminated from Martha’s Vineyard in order to see results. “The problem is not that there are deer on the Island; the problem is that there are too many (way too many) deer on the Island. They are a natural part of the ecosystem, only at a much lower density.”

A 2013 aerial survey estimated that there are roughly fifty deer per square mile on the Vineyard. Johnson is not a hunter himself. “I’ve never shot an animal,” he said. “I’m a vegetarian!” But he believes that if deer density were reduced by eighty percent, we would see a decline in tick-borne illnesses. “I’ve spent my career protecting wildlife,” he said. “I hate that I’m the one saying we need to shoot more.”

As it happens, Bologna used to love to hunt. But fatigue, combined with the fear of bringing ticks home and putting his family at risk, led him to put down the bow for many years. It was the same with his beloved surfboard: the loss of balance and flexibility long ago forced him to retire it.

This year, just before bow season opened in October, he went on a course of antibiotics and felt better than he has in years. For the first time in a long time, he enjoyed archery season.

“I definitely have more of my mobility back,” he said. “Even more importantly, I have my energy back.”

Bologna has noticed an uptick in TV commercials, articles, and doctor’s office informational pamphlets about Lyme and other tick-related diseases. He is cautiously optimistic that increased awareness will lead to more effective preventive methods and, hopefully, a viable cure.

“But for now, prevention and early detection are definitely one’s best hope for avoiding what could be years of pain and suffering,” he said.

But What About Vaccines?

Most Island pet owners are familiar with the routine – from Frontline to vaccinations – of protecting their furry friends from tick-borne illnesses. And many have wondered, “If my Mastiff can be vaccinated against Lyme, why can’t I?” It turns out that in the early 1990s, two human vaccines were being considered. Ultimately, only one, LYMERix, was approved by the FDA, in 1998. But when some who received the vaccine took to the Internet with complaints of side effects, including arthritis, their experiences became accepted lore and demand for the vaccine plummeted. In 2002 it was pulled from the market.