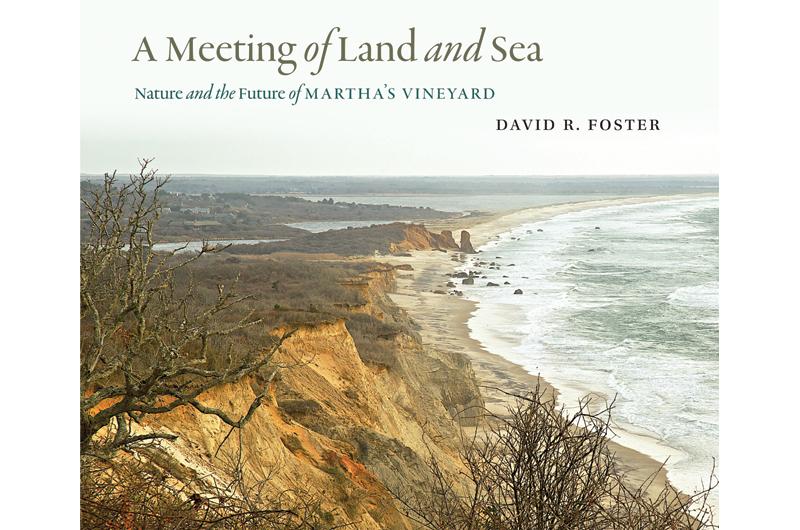

On the first page of David R. Foster’s new book A Meeting of Land and Sea; Nature and the Future of Martha’s Vineyard, the photograph of a fallen beech tree in the Chilmark Woods announces his message. It was uprooted in the 1944 hurricane and lies on its side still, but the tree has also sprouted branches of vertical growth. It brings to mind an old sloop rigged with new masts.

Over the last fifteen years, Foster, the director of the 4,000–acre Harvard Forest in central Massachusetts, and an ecologist who has studied the dynamics of landscape in forests around the world, has trained his eyes on the Vineyard, its trees and fields, ponds and beaches as part of the course of its history – natural, cultural, and human. This book is the product of his research, a rich and compelling collection of maps and photographs, charts and graphs, science and local stories that provide a new perspective on the singular and iconic island, its past and present, and in the offing, its future.

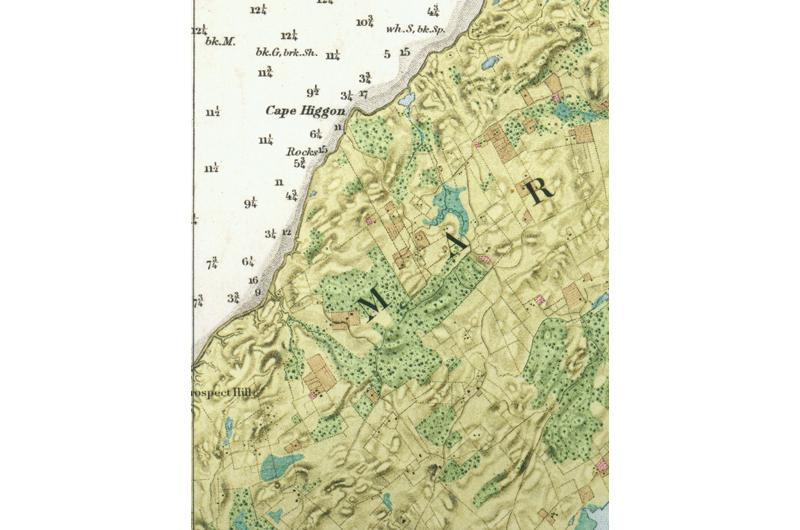

At the heart of the volume is the esteemed Whiting Map, which was compiled in 1850 by Henry Whiting of West Tisbury, the chief cartographer for the U.S. Coastal Survey and a scientist who charted the Island over several decades. Nearly every tree, fence line, and dirt road are documented here: pastures, orchards, and cutover woodlands, bogs, shoals, coastline contours, and ocean depths. It was the peak of the agrarian age on the Vineyard in the mid-nineteenth century, and the land was largely deforested and open. The whaling industry still prospered. The three named villages of Edgartown, Tisbury, and Chilmark were far-flung and of differing character. The Great Plain dominated the landscape.

As Foster and colleagues discovered, the Whiting Map is not only an extraordinary portrait of the younger and undeveloped Vineyard, but also a rare resource for evaluating the course of nature over time, for exploring the past in order to understand the present and project the future. Foster refers to 1850 as “The Landscape that Became Today,” for there were telltale signs of change in the re-greening of farmland and the surprising regrowth in the forest, just as there were glimmerings of the “leisure destination” of the future – the arrival of celebrated visitors like Daniel Webster or Nathaniel Hawthorne; the ever-expanding number of tents in the Wesleyan Grove in soon-to-be Oak Bluffs; the word in the air about troubled farms and land speculation. Foster often cites Henry David Thoreau, a kindred spirit and the subject of his first book, who wrote eloquently about the history embedded in nature. “Thoreau fits very nicely with my book,” he said recently, adding that Thoreau may have seen a copy of the Whiting Map in his travels on the coast, for he was a contemporary with a passion for maps.

Foster writes as a storyteller as well as a scientist as he traces the history of Martha’s Vineyard back to some 10,000 years of “prehistory,” when Native Americans lived relatively lightly on the Island and subsisted on its natural bounty. He reconstructs the shaping of the land that followed the arrival of European settlers, from the clearing of the forest, rise and decline of an agrarian and maritime economy, to the gradual development of a summer resort and a tourist economy. He describes prominent early Islanders who had a visible impact on the landscape: the forward-looking Dr. Daniel Fisher, who built a series of dams, millponds, and mills along the Mill Brook River; Whiting’s friend Nathaniel Shaler, a Harvard professor of geology, who began to purchase declining farms in the 1870s, which became his rambling Seven Gates Farm; Henry Beetle Hough, the Vineyard Gazette editor and author, who both popularized and protected the Island, writing in 1930 that the increased building could reach a point “beyond which the island will begin to lose instead of gaining.”

His stories are big and small, often tucked into the page as a sidebar or a lengthy separate profile – the Great Hurricane of 1635; the harvesting of drift whales; the value of scrub oak. Of more recent times, Foster recalls terrifying development schemes in the late 1950s and 1960s, which served to trigger the conservation movement. He studies the dramatic erosion of the cliffs at Lucy Vincent Beach and the 2007 breach of the barrier beach at Norton Point as lessons in the unprecedented and relentless forces of nature.

Foster looks to the future, too, addressing the uncertainties of the twenty-first century with urgency, warning of the dangers of land misuse, the rapid pace of development, and the move to full build-out, the existential threat of global climate change. He exults in the impressive record of conservation on the Island, which now has 40 percent, or 20,000 acres, of its landmass protected in perpetuity. Statewide, that figure is closer to 20 percent. The Martha’s Vineyard Commission, together with the attendant environmental organizations, has the tools, the resources, and the people to manage the land wisely now, he said, adding that “the future is not inevitable.”

Walking the land with Foster is like roaming through the pages of his book, observing his curiosity and knowledge at work, the history of the land unfolding. Out on the coastal sandplain near Quansoo Farm on the south shore, we are on ancient Native American grounds, within sight of the seventeenth century Mayhew-Hancock-Mitchell house, which may have been used by Thomas Mayhew as a missionary church and school. The fields where sheep and cattle once grazed, orchards bloomed, and potatoes grew are open pastureland now. The occasional oak and cedar trees are sheared and twisted, having taken their convulsive shapes to avoid wind damage, as Foster explained. Nearby, passing through narrow patches of “picnic woods” and onetime woodlots, Foster pointed out sprouts of wild red cedar and a “stool” of oak, a circle of growth that had sprung from the stump when a tree was cut down. Elsewhere, poking among the trees, he detected a long berm-like mound of earth that had once served as a fence in this flat and sandy ground that did not provide the makings of a stonewall. It now hosts a few pieces of scrub that look like a tentative hedgerow.

Foster grew up in still-rural Connecticut where he knew farmers and loved to drive tractors, and he appears to be in his element outdoors, tall and lanky, easy-going but intensely observant, straight hair showing under his baseball cap, a very professional camera hung around his neck. After the trek at Quansoo, he wanted to wander in what he presented as “the greatest expanse of dead woods that you have ever seen,” a quiet and historic preserve of 500 acres off Middle Road that is currently not open to the public. Where dense forest prevailed until three decades ago, a panorama of chalky and skeletal old oak trees has taken over, some still standing tall, others atilt or dismembered or fallen and uprooted, dry and leafless, the evidence of a siege of caterpillars that swept through the area in 2006 and effectively destroyed the trees. It is dramatic, a quiet and ghostly terrain in which only a scattering of beech trees that were not affected by the insects have survived. Foster surveyed the scene and said, “Isn’t this great?”

The 100-year-old oaks look like fallen soldiers, but they are part of a scene that the ecologists know is both natural and healthy, and Harvard Forest is monitoring the soils of the preserve and the pace of its regrowth. This is also historic ground, which offers a retrospective on the nineteenth century Vineyard. We are walking on former Whiting farmland, which once included the old Parsonage, where Whiting lived, and the land on the Panhandle that was given to the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society, which Whiting and other social leaders founded in 1858. On our route through the preserve, we encounter a stretch of savannah that has been cleared of dead trees by machine and is ready for cultivation by a local farmer. “Farmers may be our most important land stewards,” said Foster, who is now pursuing the prospect of conservation partnerships with the farming community as ardently as the lessons of nature that are stored in its landscape. In his conversations with Islanders, he has been able to mine the memory of locals who have experienced the land firsthand, in all its challenges, diversity, and beauty. In important ways, it has guided his work – “there is no resource more fundamental than the people.”

Nearing North Road, we come upon one of the series of millponds and dams that Dr. Fisher created and the old Fisher icehouse. Looming in the distance is the terrain on which Shaler assembled Seven Gates, its land now in conservation. It is a piece of the old moraine and it looks like foothills, as rocky and dense as a wilderness. Foster marvels at the continuity of the Vineyard landscape in the face of constant change. Though he warns that “we are at a crossroads,” he believes the Vineyard is better positioned than many other places to face the many environmental challenges ahead due to the efforts of past advocates and the resiliency of nature.

“The land is intact,” he said, with a show of pride in both nature and its caretakers.