Mention the Vineyard to most people and they think first and foremost of the ever-changing, always-remarkable ocean that surrounds it – the beaches, the views, the taste of salt air. And who can blame them? The sea, after all, is what makes the Island an island.

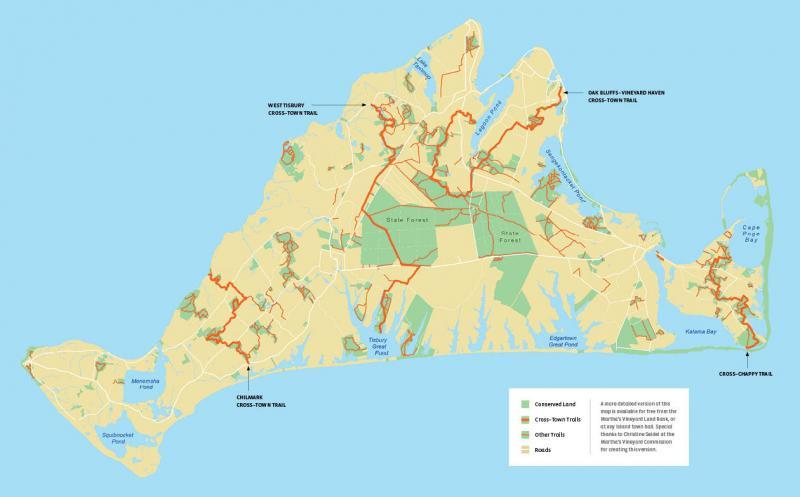

But there is also a complex interior landscape of conservation properties and connective trails for those adventurous enough to look inward and seek them out. Pick up a Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission map at a town hall, a local library, or look at it on the web and how can you not be intrigued by the tiny yellow lines that delineate the vast and largely hidden system of routes that overlay the Island like a silky spider’s web? “Healthy and vibrant,” is how Bill Veno, trail planner for the land bank and the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, described the trail network. “There are a lot of users, but they’re not overused.”

Plenty of hikers, dog walkers, mountain bikers, horseback riders, nature enthusiasts, and asylum seekers find their way to various short pieces of the system throughout the year, especially those trails that lead relatively quickly to a secluded beach or a magnificent overlook. Particularly eye-catching on the land bank map, however, are the larger, orange and yellow dashed lines labeled “cross-town trails.” One of these starts on the shore of Lagoon Pond in Vineyard Haven, loops inland to sections of West Tisbury and Edgartown, and then into Oak Bluffs where it ends near the ferry terminal, making for a great day adventure. Another begins at the lower end of Lambert’s Cove Road and extends all the way to Tisbury Great Pond, a rewarding way to ride a bike to the beach. And the most masterful day adventure of all may be the “cross-Chappaquiddick” trail, which takes you all the way from Wasque Point to Cape Pogue Bay and back, if you so desire.

Cross-Island trails? Who knew? “The first time I know of a reference to a cross-town trail,” said James Lengyel, executive director of the land bank, “was in a Chilmark Master Plan from the mid-1980s.” That plan envisioned a coast-to-coast spine trail off of which would come loops that would circle back to the spine. The land bank, which was established in 1986, uses a two percent surcharge on most real estate transfers to purchase public conservation land in all six towns. Borrowing the concept of interconnected trails from the Emerald Necklace in Boston, they asked each town’s land bank board to help plan for a cross-town trail. For the three down-Island towns, the trail would start somewhere in the downtown, then merge in the Manuel F. Correllus State Forest, and connect from there up-Island. “A lot of that has been formalized,” said Lengyel. “There’s a lacuna here and there – well, really there are plenty of them – but that’s what the land bank and other conservation groups are working on.

“We are charged with trails and trail easements and putting together agreements,” he went on. “Trying to be as objective as I can be, I think that we are in remarkably good shape. The land bank’s goal is that when everything is done, there will be a north-south, east-west, coast-to-coast trail system.”

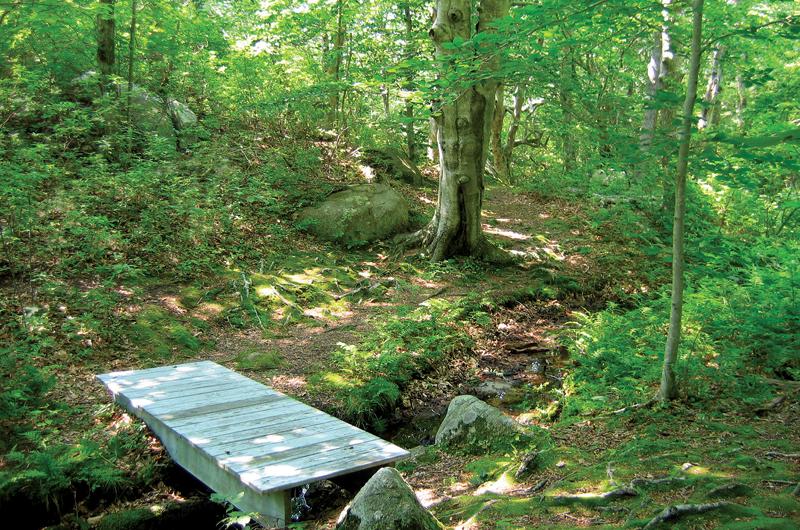

Trying to follow the spine today on a mountain bike, especially in the hills of Chilmark or the woods of West Tisbury, you soon discover an almost dizzying number of loops and trail opportunities. At the trailhead, the white land bank signs lure you into its protected environment, where birdsong is more plentiful than people-talk. You drift along in a calm state of bliss, your senses elevate to the sounds and smells of the moment, and then, you invariably arrive at a crossroads. A tiny sign of a red, blue, or yellow nailed to a tree invites you this way and that, leaving you to choose your path but not always telling you where you’re headed.

Sometimes a trail is marked by a Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation sign, or a Trustees of Reservations sign, welcoming you onto land protected by those organizations. Other signs note that the trail is just an easement through private property, made available by the generosity of private land owners. The beauty of the system, both as it currently exists and as it’s envisioned, is that it doesn’t attempt to start from scratch, but it attempts to leverage the success of all the conservation efforts by connecting them to one another.

“You can make some great connections from one property to another using a variety of trails and dirt roads and ancient ways,” explained Adam Moore, the executive director of

Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation. “You can get around the Island without seeing a lot of people, and you can see a lot of the countryside that way.”

Sheriff’s Meadow, which was founded fifty-seven years ago by Vineyard Gazette editor Henry Beetle Hough and his wife, Elizabeth, now owns or holds conservation easements on nearly 3,000 acres. Many of its properties are crucial to the trail system, but Moore is quick to credit his colleagues at the land bank for the lion’s share of the organizational work. “Bill and James have really done a good job putting the trails together. They are really the result of a lot of hard work; they take lots of negotiation and planning.”

Despite the best efforts of the sign crews and the land bank map, riding or walking in circles is generally what happens to the novice who sets off overland on the Vineyard. You could look at that as all part of the fun – getting temporarily lost on a mid-sized island crisscrossed by paved roads and surrounded by water isn’t quite as worrisome as it might be in, say, a mountain biking mecca such as Moab, Utah. Or you could tag along behind a local mountain-biking enthusiast, in my case Edgartown resident and man-child Michael Berwind. Pedaling furiously on a borrowed high-end bike trying hard to keep up with him as he rode effortlessly over the trails that lead from the middle of Edgartown in any direction as far as you want to go, the varied nature of the trail system rapidly becomes clear. “The state of the trails varies from pristine to unrideable,” he said, though it seemed from my perspective that “unrideable” was most definitely in the eye of the biker.

From the vantage point of a bike, you notice quickly the different types of trail. Land bank trails are spacious and well maintained. (“We call it gossip width,” laughed Lengyel. “Our goal is that two adults can walk abreast and be able to converse and not pick up a Lyme infection.) Sheriff’s Meadow trails, on the other hand, tend to embrace you; they are intimate, single-track trails nestled more in nature. And then there are the trails that only the serious riders like Berwind know, wisps of paths seemingly maintained only by knobby tires and deer hooves. Moving quickly over lumpy sand, packed dirt, bumpy tree roots, low-cut grass, and slippery wood chips, and then weaving through low brush and low branches, which Berwind stops to cut with his pocket saw, it is a seamless adventure with a knowledgeable guide.

“I think there are a lot of different people on the Island, and many people like the wide and straight paths and other people don’t,” Berwind said at a rare stop. “It’s a fragile environment. The top soil is thin; you have to lay them out very carefully with thoughts about erosion and use, then connect them all up and safeguard them.”

Moore, of Sheriff’s Meadow, agrees. “I think it’s positive,” he said of the state of the trails generally. “But there’s a lot more to do. We want to set a standard on good blazing and maintenance. There are more connections to be made both on land that we already own and on land that we hope to conserve in the future.”

A hiker or a biker planning an off-road outing with the aid of a land bank map slowly understands the story it tells. A plethora of yellow trails moves consistently through the down-Island towns (including the down-Island side of West Tisbury) and the state forest. There’s a robust network of trails and ancient ways in Chilmark, as befits the town where the cross-town trail idea was born. But there is a noticeable lack of unpaved routes going east-west to connect the down-Island trails with the Chilmark trails. And there are virtually no trails other than discreet loops west of Peaked Hill in Chilmark or in Aquinnah. Though the land bank and other conservation organizations will doubtless continue to acquire critical parcels of undeveloped land outright, major progress on extending and improving the trail network will more likely come through easements across farms and residential communities’ land that are not publicly owned but may already be under conservation or agricultural restriction.

“People are afraid of the unknown, afraid of the loss of privacy, and whatever else they can imagine,” said Moore. “But landowners are critically important. There’s always a dialogue going on, and sometimes this can take decades.”

Historically speaking, that’s probably an appropriate time frame. After all, it took decades to lose what was a long tradition of public access. Many old-timers on the Vineyard remember a less crowded time when no one cared if you walked along a field or down a dirt road to the beach. “The land bank cannot recapture all of the freedoms and casual liberties of the Island’s past,” explained Lengyel, “but it can recapture some.” The wave of privatization and closing off of walking access began in the 1950s and accelerated in the decades of development that followed.

“We are each committed in a positive way,” said land bank trail planner Veno of the various players in the effort to reconnect the lines for walkers, bikers, and other non-motorized travelers. “The land bank keeps on trying. They know we’re going to be here a while, and it can take a long, long time.”

5 comments

5 comments

Comments (5)