A year ago, in the spring, writers Geraldine Brooks and Tony Horwitz invited some friends to their West Tisbury property for a “Help the Alewives” party. A dam downstream in the Tiasquam River had been leveled, and as a consequence, for the first time in eighty years or more, herring had arrived at the dam on Brooks and Horwitz’s property, but they were stuck there.

“It was quite comical,” says Horwitz. “We were all out there with nets trying to catch the herring and throw them over the waterfall. We didn’t have much success.”

Now, the couple has applied for permission to install a herring ladder at their dam. They are, in fact, required by law to provide “fish passage” on their property, but, notes Brooks, “we’re not allowed to do it until we’ve been through a ton of permitting.”

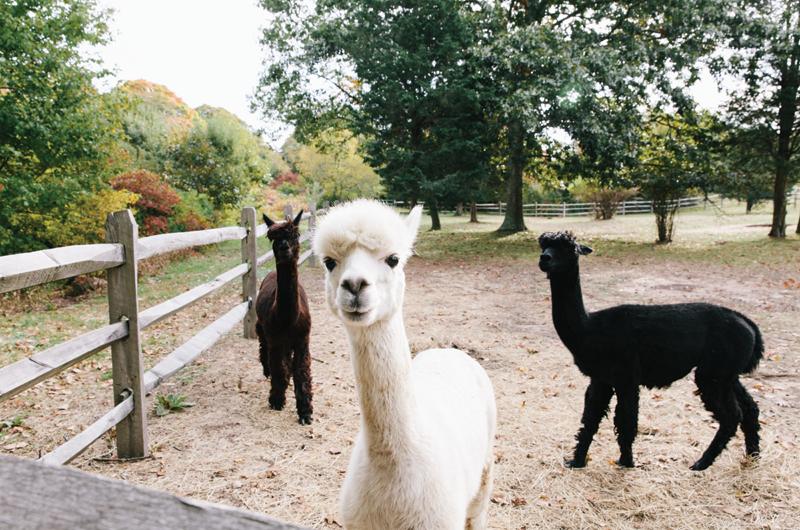

Caring for herring is but one small example of the kinds of real estate maintenance calisthenics in which Brooks and Horwitz engage on an ongoing basis. The owners since 2010 of a historic West Tisbury property of nearly five beautifully landscaped acres encompassing a stretch of the Tiasquam, a dam and two spillways, a pond with a peninsula that is almost an island, a paddock housing three alpacas, an eco-friendly swimming pool, a renovated barn, and a farmhouse that may date to early 1700, the pair have their hands full when it comes to property maintenance.

“When you get an old property like this,” says Brooks, “you don’t really own it; you’re a custodian of it for a very brief period of time in its life. That’s why we haven’t changed it much. What gives you the right to come in holus-bolus and dramatically change a property this old? I mean, a little modesty, please. There’s so much here that tells the story of the Island. I feel this land, and this house, embody the Island’s story in so many ways.”

The first known European owner of the property was Colonel Benjamin Church, who bought the land from the Takemmy people, one of four Wampanoag Sachem tribes on the Island at the time. In 1668, Church dammed the river and built the Island’s first gristmill. Later, he left the Island and became captain of the country’s first Army Ranger force, employing Praying Indians (those who had befriended the European settlers and converted to Christianity) as scouts and teachers of Native American warfare tactics. With their help, Church and his men were able to locate, ambush, and raid Indian camps and settlements. In 1676, Church led a group of Rangers in search of King Philip, a Wampanoag sachem also known as Metacomet. Metacomet, who had initially befriended the colonists and who liked to purchase his clothing in Boston, later led Native American forces in an effort to stop colonial expansion and encroachment. Church and his Rangers caught up with Metacomet in a Rhode Island swamp, where Metacomet was shot and killed by one of Church’s Praying Indians. Metacomet’s body was drawn and quartered and the parts hung from trees. His head was mounted on a pike at the entrance to Fort Plymouth, where it remained for more than twenty years.

Subsequent owners of Church’s property were less gruesome characters – a variety of Looks, Merrys, and Mayhews. The original house was a modest Georgian or side-gabled colonial, just two floors and a couple of rooms per floor. Later, a second small house, likely also of early 1700s vintage, was moved to the property and added onto the existing house. Somewhere toward the end of the nineteenth century, it is believed, the “new” wing, now housing the kitchen downstairs and the master bedroom upstairs, was added as well.

In 1923, John Mayhew Sr. bought the house from Luther Norton. Mayhew found the dam in disrepair. The pond had disappeared, and the land had reverted to pastures, on which cows were grazing. He asked someone for an estimate on what it would cost to repair the dam and restore the pond, and then he and his family left for an extended stay in Asia. When they returned, they discovered that their request for an estimate had been interpreted as a work order: the dam was fixed and the pond was back.

Mayhew’s widow, Helen, sold the house in the mid-1960s to David Douglas and his fiancée Jenifer Breasted. When they later split up, the house was sold to a couple who did considerable restoration work on the house, inside and out. After a few more turnovers, Laura Campbell and Lennie Baker, the latter of whom was a saxophone player and a member of the oldies rock group Sha Na Na, bought the house in 1992 and moved in.

“So now the place was owned by a rock star, which sort of encapsulates the changes that have happened on the Island,” notes Horwitz. In a kind of two-degrees-of-separation story typical of Vineyard life, Laura Campbell married David Douglas after she and Lennie split up, and Douglas moved back into the home he’d lived in years earlier. It was these two who sold the house to Horwitz and Brooks in 2010.

But meanwhile, while Laura and Lennie were still together, when Lennie was away on tours, Laura gardened. “And I’m the grateful beneficiary of that,” says Brooks. The property’s landscaping is exquisite in an unselfconscious, understated way. There are tall grasses by the stream, flower beds near the house and against stone walls, blueberry bushes, and numerous fruit trees, including a few very old, very large apples and pears.

“There’s also a good crop of poison ivy,” quips Horwitz. “I just have to look at it and I get a rash. I usually get it three times a summer.”

Brooks spends a good deal of time gardening, though she admits to occasionally “calling in the cavalry” of landscapers when necessary. The family tries to plant a tree for everyone’s birthday, and so far they’ve put in several birches, an ornamental pear, two fruiting cherries, one flowering cherry, and a hornbeam. Brooks maintains her flower beds and a vegetable garden, clears invasive plants when they get out of hand, plants grasses and other marshy natives in hopes of attracting a muskrat who used to live near the stream, and now also works in the aquatic gardens around her swimming pool, which serve as a natural, non-chemical filtration system for the pool’s water.

“I never wanted a pool,” says Brooks. “I mean, you’re living by the beach here. But along with the house came this crazy pool: it was eight feet deep at every level, with no shallow end. It looked like something you’d train a Navy SEAL in – strap weights to his ankles, throw him in, turn on the fire hoses, and see if he could swim to the surface. It was a bit of a death trap.”

In addition, it leaked and required a lot of chemicals to keep it clean. The last straw, says Brooks, came one day when, lying by the pool, she noticed that the roses needed deadheading. She stood up with her clippers and went straight through the decking.

“I came up with a piece of deck the size of a grilled cheese sandwich sticking out of my leg. I realized that this could have happened to one of the kids. It was time to fix the pool.”

Hence, out went the death trap and in went a surprisingly natural-looking rectangular pool, surrounded by local stones and the filtering pools, in which frogs wallow among the plants. Brooks has worked with the Polly Hill Arboretum and the conservation commission to find native plant varieties that suit the purpose – reeds, water lilies, etc. The system uses very little energy and absolutely no chemicals, though the pool must be vacuumed weekly, as it develops what is called a bio-film (“a nice word for ‘scum’,” notes Brooks).

The pond created by the dam is shallow and not especially suited to swimming, in part because it is mucky-bottomed, and also because it is home to a number of large snapping turtles that Brooks and Horwitz have occasionally observed hauling themselves out of the water to lay their eggs on the shore. The couple sometimes paddles around in a kayak, but most often, especially at sunset, they enjoy sitting in Adirondack chairs out on the peninsula (a flat, grassy oval created when a previous owner dredged the pond), enjoying the peaceful views and watching the birds and animals – swans, ducks, geese, osprey, otters, turtles (painted as well as snapping), and a flock of turkeys who wander on to the property a couple of times each day.

“It’s like a secret island,” says Horwitz. “It feels to me as though we could be in New Hampshire or Vermont. It’s very private.”

Of course, the pond and its dam and two spillways require some maintenance. A spillway is a structure used to control the release of water from a pond or reservoir. In this case, the spillways are simple constructions of boards placed one atop the other. In the days when there was a mill on the property, boards could be raised and lowered to increase or decrease the water flow through the mill. Now, during flood conditions, when water reaches the top of the spillways, it flows over them, preventing it from flowing over and potentially damaging the dam itself.

“We had a sort of tragicomic episode two years ago when both of the spillways broke,” says Horwitz. “The pond drained out in two hours, and some of our neighbors were having a

wedding two days later.”

“Well, really only one spillway was broken,” corrects Brooks, “but we thought it was the other one and started working on it until we realized that it was fine, and it was the other one that was broken. Anyway, there were fish flopping around in the muck, and the birds were acting as though we’d opened a deli. We did a rushed emergency fix with sandbags and boards.”

“When you live in an old house,” says Horwitz, “you have to be prepared to take on a constant project of restoration and maintenance.” Fortunately, the couple has considerable experience with old houses, having lived in four others prior to this one: the first, in Australia, dated to 1850; the second, in London, was built in 1790; the third was an 1810 home in rural Virginia; and finally, the couple lived in a house on Main Street in Vineyard Haven that was built in 1840.

Horwitz describes their current home as “high on charm, low on practicality.” The house has no serious structural issues, but it is sagging perceptibly. The floors slope so much that all the cabinets and tables have to be on shims. Where one cabinet stands in a front room, there is a two inch difference in height from the front legs to the back. “You wouldn’t want to play marbles here,” says Horwitz.

None of the windows or screens fit perfectly within their frames, and every window is different. The staircases, with steep risers and narrow treads, are nowhere near what would now be considered “code.” Brooks notes that when Barnes Movers arrived with the family’s furniture, they looked at the main staircase dubiously and asked whether there might be another one. Brooks replied, “Yes, but it’s even worse!’’ When the couple’s younger son, Bizu, now a seventh grader, was studying for the SSATs, he was asked in the vocabulary section to name a synonym for the adjective “antique”; he wrote “rickety.”

But the house is a classic example of early-eighteenth-century construction – timber framed, using both wooden pegs and hand-forged iron nails to join posts to beams, with gunstock posts (vertical supports that are wider at the top to support upper floors and/or the roof) and beams that were all hand-hewn. It is well situated, in a protected dell to avoid excessive exposure to wind, and oriented so as to take maximum advantage of warmth from the sun.

Brooks thinks with awe that this house was standing before European settlers arrived in Australia (her native land). She is equally impressed when she considers what it must have been like to live in the house before the advent of modern conveniences – hauling water from a well, getting up before daylight to keep the fires burning for heat and cooking. So what if the closets are small and few? “We just have fewer clothes,” she says. Living in this house helped in the writing of her novel Caleb’s Crossing, set mostly on Martha’s Vineyard in the early days of European settlement here.

“She used it as the model for the Merry Farm in the book,” says Horwitz, “and living here helped her imagine what domestic life was like at the time.”

When the couple bought the house from Laura Campbell and David Douglas, they replaced a few windows, did a bit of interior repainting, and, as their only major change, moved the kitchen to what had been the living room – a larger space with better views. “Since we kind of live in our kitchen,” explains Horwitz, “we wanted it to be the nicest room on the first floor.” They posit that the kitchen had been in this space sometime in the past, because old photographs show a hearth in the room, and there is a well in the floor.

As of this writing (January 2016), a second substantial renovation project is taking place on the second floor: two non-functioning bathrooms are being removed and a larger, functional bathroom is being installed. Until now, use of the showers caused leaks through the ceilings below. “We have a hand-held thing in a tub,” says Horwitz, “but it’s dubious. There’s an outdoor shower that we can use in warm weather, but come winter, the troops get a bit whiffy around here.”

During the bathroom makeover, the family is living in the old barn, which they renovated and winterized a few years ago. They thought they would be there for only a few weeks, “but now I think we may very well die here,” says Brooks. “Once the workers got started, they realized that no one knew what was holding the house up. They’ve spent weeks trying to figure that out. Luckily, they have it now, so they’ve stopped reducing the house to matchsticks and have started putting it back together.”

Fortunately, the barn – which a previous owner had redecorated in what Horwitz calls “a sort of sixties orgy style” and Brooks calls “Barbarella” – is now a comfortable guest house in a rustic style that is more consistent with the character of the main house. Horwitz’s office is also in this building. He describes his work habits as “untidy,” and likes having a separate office where he can be as messy as he likes without it bothering Brooks. Upstairs, there are storage areas built under the eaves, where the two writers keep the many papers and other materials they acquire when researching their books. At the back of the barn is the alpacas’ winter home – a paddock and a shed they can enter for shelter.

Brooks and Horwitz believe that this property is their final home. Having traveled extensively as journalists and moved numerous times, they are glad to be permanently settled, though they admit that they miss looking at Vineyard real estate. Brooks’s first exposure to Martha’s Vineyard came through a pen pal she acquired at the age of eleven through the Mr. Spock Fan Club, with whom she corresponded until she was twenty-five. This pen pal summered in Menemsha, and Brooks recalls receiving beautiful post cards during the summer months, filled with descriptions of Vineyard summer life. Years later, when Brooks was dating Horwitz and attending graduate school at Columbia University in New York, she told Horwitz that there was one place in the United States she wanted to visit before she left the country.

“She could have said Fargo, North Dakota, but she said Menemsha,” Horwitz remarks. Horwitz had become familiar with the Island when his parents rented a house in Woods Hole while he was growing up, and had later paid several visits to a college roommate who had a place in Aquinnah. So the couple came to the Vineyard, and Brooks “sensibly fell in love with the place.” While working overseas as journalists, they returned when they could.

“We always wondered what year-round life would be like here,” says Brooks. “Then we got a fellowship at Harvard, and we came out almost every weekend. We loved the beauty of the place in all seasons, and the winter community was so cool.”

When the sprawl of greater Washington, D.C., began to encroach on the rural Virginia village where they were living, they decided to make the move, arriving here in the winter of 2005-6. They’ve never looked back.

Down the line, Brooks envisages creating a master bedroom and bath on the first floor “for our dotage.” Having cracked her pelvis after a fall from a horse a couple of years ago, and been unable to negotiate the house’s iffy stairs, she realized that a downstairs bedroom and bath would be “a very nice thing.” But for the time being, the area where it will go remains a music and homework room.

A few years ago, at the Granary Gallery, the couple bought an antique painted kitchen cabinet that they were told came from an old Island house. As the paint on their kitchen floors has begun to wear away from foot traffic, it has recently revealed a previous color that is precisely that of the cabinet.

“I’m pretty sure the piece came from this house,” concludes Brooks. “So it’s come home.” As, indeed, have Geraldine Brooks and Tony Horwitz.

6 comments

6 comments

Comments (6)