It’s hard to find a copy of The Island Steamers in anything better than frayed condition, so well thumbed are most of them. Indeed, Vineyarders and visitors who love the story of the Island steamships and ferries – the history goes back to 1818, only eleven years after the launch of Robert Fulton’s North River steamboat – have been waiting two generations for a definitive new book on the subject to arrive. This spring it finally does.

The two great virtues of Steamboats to Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket (Arcadia Publishing, 2015) are the qualifications of the author and the uniqueness of the pictures he presents. William H. Ewen Jr., who with his wife, Sue, has been a summer resident of the Camp Ground of Oak Bluffs for most of the last forty years, is an artist, historian, and lecturer on steamers of the eastern seaboard and beyond. Like Morris and Morin before him, he is a particular authority on the vessels of the Island route.

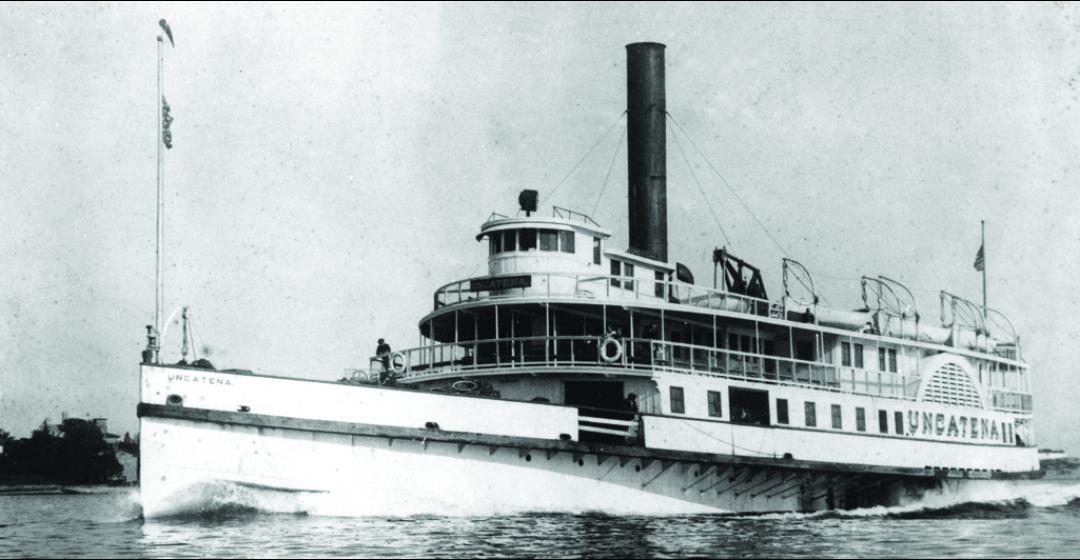

For photographs, Ewen drew on two nationally famous collections of steamboat artwork and memorabilia, one belonging to his late father, William H. Ewen Sr., and the other to himself. The Ewen family lived in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, and in the early years of the last century, when still a boy, his dad would row out into the Hudson to meet the boats steaming up and down the river and photograph them. In his own boyhood, Bill would row out with his father and do the same.

“A number of the captains knew him and blew whistle salutes as they went by. And I was just so impressed with the grace and the speed of the boats that I would go home and try to start drawing pictures. That was probably my first step into artwork,” he said. The new book breaks down the Island story into clean, chronological chapters with cogent introductions, and presents photos of our vanished steamers, many from the two Ewen collections and never seen by the public before.

It also evokes the way the lost steamers moved through the water, what made them look so different from one another, and how it might have felt to sail aboard them. “A general word would be aesthetics, all the things that make it up,” said Ewen. “There was grace and attention to detail, the ambience, the chime whistles, big flags flying from flagpoles, the boats painted brightly white – there was something about the visual grace and experience of riding these steamers.”

The new book does not cover the big-box modern ferries that we ride today. But Ewen is largely responsible for something that begins to set them apart from one another – he is leading the effort to install authentic, hollering steam whistles aboard the diesel boats running to the Vineyard, and it is thanks to him the wail of old-time steamers will cry this summer from two Island diesel ferries, the Martha’s Vineyard and the Island Home.