No one involved could have imagined it. Not the workers trudging through the snow to begin construction of the new whaleship at the Hillman Brothers Shipyard in New Bedford in January of 1841, nor the owners paying for the ship, nor the people who were to sail on her in the years ahead. None of them could know that this ship, set to join the whaling fleet at the beginning of what would be the busiest, most profitable decade of whaling under sail, would, in her eighty-year, thirty-seven-voyage career, sail to the end of the industry she was built to serve. Nor could they have imagined that she would become the last remaining vessel of a whaling fleet that numbered over twenty-seven hundred vessels, a glorious remnant of a global industry that encompassed more than two centuries of American maritime history.

Back in January of 1841, the Morgan was just another whaleship under construction at the highly respected Hillman Brothers yard, one of seventeen whaleships the brothers built between 1827 and 1852 in the busiest whaling port in the world. Many of the leading families in the whaling capital of New Bedford originated in Nantucket or the Vineyard, and Jethro and Zachariah Hillman were no exception. They learned the art of shipbuilding from their father, a shipwright who had learned the trade on Martha’s Vineyard before moving from Chilmark to New Bedford in 1788.

This is just the beginning of the multiple ways the Morgan and Martha’s Vineyard are intertwined. Six of the twenty-one captains of the Morgan during her long whaling career came from the Vineyard, including her first captain, Thomas Adams Norton of Edgartown, whose great-great nephew S. Bailey Norton lives on North Water Street today. Seventeen members of her original crew were Vineyarders, as were many sailors on later voyages. Even the famous Vineyard Gazette editor Henry Beetle Hough, who through his writing did much to keep the history of whaling alive, was the Hillman brothers’ great-great nephew.

Charles W. Morgan, the ship’s namesake and principal owner, wrote in his diary on July 21, 1841 that it was “a fine warm day – but very dry.” A prosperous Quaker entrepreneur and abolitionist, his holdings illustrate that while the product of whaling lit the world and lubricated the Industrial Revolution, its profits flowed into many aspects of the nation’s expanding economic system. In addition to the ten whaleships he owned wholly or partly, he was invested in a spermaceti candleworks, an ironworks, textile and paper mills, coal mines, railroads, insurance companies, banks, and land in the Midwest. At heart, though, Charles W. Morgan, the man, was as much a whaler as the ship with his name on her stern. “This morning at 10 o’clock my elegant new ship was launched beautifully from Messrs. Hillman’s yard – and in the presence of about half the town and a great show of ladies,” the journal continues. “She is to be commanded by Captain Thomas A. Norton.”

The Morgan came to be known as “a lucky ship,” and she was, but the better part of her luck no doubt came from carrying capable captains and crews. The thirty-two-year-old Norton had previously sailed on several of Morgan’s other ships, including as captain of the Hector on two successful voyages between 1834 and 1840. He recruited an aforementioned seventeen sailors from his home Island, most of them teenagers and some of them related to one another or to their captain. They came from Edgartown, Tisbury, and Chilmark. One, Zanus Gould, was a Wampanoag.

Given the countless dangers and dismal conditions of the trade, and the fact that voyages regularly lasted three to five years, one might wonder why anyone would choose to go whaling. But on the Vineyard, where the finest houses and most elegant churches were all built with whaling money, and where the potential for both disaster and profit in the fishery were well understood, to go “a-whaling” was a natural choice for boys and young men. The Vineyard served as home port for far fewer ships and voyages than its near neighbors New Bedford and Nantucket, but the Island provided an outsized number of the officers and crews for their ships from all ports.

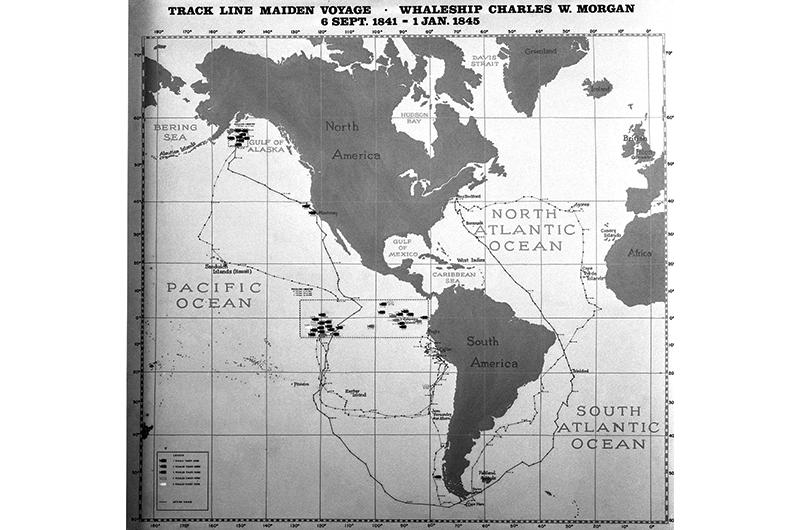

When they returned to New Bedford after three years, three months, and twenty-seven days, the hold was full of sixteen hundred barrels of sperm oil, eight hundred barrels of whale oil (oil from any other type of whale), and ten thousand pounds of whalebone. Captain Norton, who had a one-eighth share of the ship, took his profits and retired in Edgartown at age thirty-seven. If he had initially gone to sea in his mid-teens, which is likely, he had spent almost half of his life at sea and was ready for a quieter existence. But he apparently never forgot his last ship: in the late 1840s he and his wife named a son Thomas Morgan Norton. It was not a family name, says S. Bailey Norton today, “they named him after the ship.”As a harbinger of what was to come in the Morgan’s career, the first voyage was a success. Second mate James C. Osborn, of Edgartown, began his journal of the voyage with the hope “may kind Neptune protect us with pleasant gales, and may we be successful in catching sperm whales.” He was not disappointed. They didn’t find whales until they were around Cape Horn and into the Pacific, but the fishing was good in the equatorial waters a thousand miles off of South America and around the Galapagos. They killed whales in the Gulf of Alaska and off of Monterey, California.

Over the course of the next eighty years the Charles W. Morgan set sail in search of whales another thirty-six times. She hunted in every ocean, and a list of her ports of call reads like a geography quiz: Madagascar, Mauritius, Guam, Bonin Islands, Vladivostok, Shantar Islands, Cabinda, Tristan de Cunha, Rio de Janeiro, Valparaíso, Honolulu, on and on and on. Fourteen of those voyages had Islanders at the helm, and though crews became increasingly international as the nineteenth century progressed, it’s safe to say it was a rare voyage indeed that didn’t have at least one Islander on board.

The last Vineyard captain to sail the Morgan was Benjamin D. Cleveland of West Tisbury, who brought her out of retirement in 1916 and nearly regretted it. The ship had been laid up for three years and it seemed as if she had sailed her last voyage when Cleveland, a veteran whaling captain nearing his seventy-fifth birthday, decided he wanted to make one last voyage. He bought the Morgan from the J. & W. R. Wing & Company, ending their fifty-three-year ownership of the ship, and announced he would sail to Desolation Island in search of sea elephant oil. Other investors weren’t so enthusiastic about the old man’s plans to take a ship that was older than he was halfway around the world, but once again a stroke of luck appeared, this time in the form of a movie company looking for a ship it could fix up to appear in a silent film called Miss Petticoats. A deal was struck and Cleveland used the proceeds to prepare the Morgan for the voyage, and set sail from New Bedford on September 7, 1916.

Desolation Island is located in the south Indian Ocean on the edge of the Antarctic Sea, eleven thousand miles from home, and its name is well earned. The Morgan arrived there on February 7, 1917, and for nearly four months the crew went ashore to kill elephant seals. Not even the Morgan was immune from all tragedy, and on April 19 one of her whaleboats heading ashore was capsized by a large wave. Four of its six-man crew, dressed in heavy clothing, drowned. Still, the voyage was a success as far as oil was concerned and they departed from Desolation Island on May 12 with eleven hundred barrels in the hold.

When they arrived at the island St. Helena, however, they learned that the First World War had begun and German U-boats were on the prowl for enemy merchantmen. Captain Cleveland immediately decided to head for home, which he did by staying out of the shipping lanes and sailing to the West Indies. From there, after narrowly missing a floating mine, he set a course into the Gulf Stream, again out of the usual travel routes. He crossed the busy shipping lanes near New England at night and finally, by staying close to the dangerous – but well known to him – shoal-riddled south shore of the Vineyard, made his way back into New Bedford to a hero’s welcome. No fewer than eleven former whaling captains were on hand to greet him when he stepped ashore.

The Morgan sailed on three more voyages under non-Vineyard captains before coming home to New Bedford from the final one on May 28, 1921. By that point there was only one other whaleship left in New Bedford, the Wanderer, and both relics were spruced up to be used in the 1922 silent film classic Down to the Sea in Ships. After that, however, it appeared the Morgan would suffer the same end as so many of her sister ships: to rot, to sink, perchance to burn. The latter very nearly happened in June of 1924 when the Vineyard steamboat Sankaty caught fire and drifted up against the Morgan where she was laid up along a wharf in Fairhaven. Only quick work by the Fairhaven Fire Department saved the ship. The Wanderer was less fortunate: that same summer it set off on what many thought would be the last whaling voyage from New Bedford and only made it across Buzzards Bay before wrecking on the shore of Cuttyhunk in a storm.

Green moved the Morgan to his Round Hill estate near New Bedford, put her into a sand berth in the spring of 1925, and opened her to the public in the summer of 1926. He also hired George Fred Tilton to supervise the ship’s overhaul and serve as her “captain” when she was opened to the public. A retired whaling captain famous for his three-thousand-mile trek across Alaska to secure help for several steam whaleships trapped in the Arctic ice in 1897, and a member of the well-known Chilmark Tilton clan, Tilton was the real thing. He was also a great storyteller and ambassador for the ship and for whaling who mesmerized visitors with his tales and his knowledge. Nearly two hundred thousand people visited the ship in that first year.The Morgan was now the last of her kind, but a lucky ship is a lucky ship, and a savior appeared. The loss of the Wanderer galvanized Colonel Edward Howland Robinson Green to preserve the Morgan. He did so, he said, not only because his grandfather had been the Morgan’s second owner, but because she represented an important chapter in American history. As the son of the famous investor Hetty Green – the so-called “Witch of Wall Street” – he had the wherewithal to do it.

“Perhaps we two, the ship and myself, compare pretty favorable,” Tilton wrote about the Morgan near the end of his autobiography, Cap’n George Fred Himself. “She is considerably older than I am, being eighty-seven years off the stocks, but we both of us have been tumbled around by the waters of every ocean, and now that we are not wanted to hunt whales anymore, we are laid up here so that people can get some idea of how the business used to be done. The ship is on exhibition, and I sometimes think I am too.”

Both captain and ship were landlubbers at that point, but Tilton, for one, didn’t think it needed to be that way. “I have said that the ship lacks life. T’is so, just as I do with soil under my feet, but there is this consolation. Neither of us is dead or near to it. Shovel away the sand from the Morgan’s sides, caulk her, and she’ll go around the world – and I can sail her, by Godfrey.”

Tilton died in 1932, but when you look at what now lies in store for the Morgan, it seems he may have been not just a raconteur, but something of a prophet. In 1941 Mystic Seaport took possession of the ship and moved her to Connecticut. In 2009 – under the leadership of board chair Richard Vietor of Edgartown and president Stephen C. White, whose family have been seasonal residents of Edgartown for many generations – Mystic Seaport announced it would not only restore the Morgan, but sail her again this summer. The decision would have pleased Tilton. As the ship still has no engine, he no doubt also would have appreciated the donation of a professional tugboat and crew for the entire voyage by Ralph Packer’s Tisbury Towing Company.

It is appropriate, given her many Vineyard connections, that she make her first visit to the Island. In a sense, because she is sailing again, Tilton and all those other Vineyarders who sailed and saved her are coming home too.

Matthew Stackpole, a former Vineyard resident, is major gifts officer and ship’s historian for the Charles W. Morgan restoration at Mystic Seaport.