Gay Head Light

A woman cannot help but express her disappointment when she learns that the Gay Head Lighthouse is not open for public tours the spring day she visits the site. “We came all the way from the Philippines to see this!” she says. One of her companions offers consolation: “I’ve been inside a bunch of times,” he tells her. “There’s nothing in there but stairs.”

The man is pretty much right. The lighthouse interior consists of three flights of stairs, one ladder, a bank of batteries and electric panels, and at the very top, in the glass cupola, two revolving lights – one white, one red – which alternate every seven-and-a-half seconds.

He’s also wrong, because the Gay Head Light is far more than the sum of its parts. It is a working monument to the history of this place.

The story starts with an underwater ledge running from the cliffs westward out into Vineyard Sound. This ledge, in Wampanoag legend, is Moshup’s Bridge, an unfinished road to Cuttyhunk. To mariners, the ledge is known as Devil’s Bridge, a significant rocky hazard that has claimed ships and lives.

In the late eighteenth century, authorities in the new country, the United States of America, determined something had to be done to aid navigation around the ledge. They decided to erect a lighthouse, the first to be built on Martha’s Vineyard.

President John Adams signed the document that officially took two acres of land above the cliffs for the purpose of a lighthouse on July 1, 1799, and the light went into service in November that same year. Alexander Hamilton cut the check that paid for the wooden structure. Paul Revere supplied the metal used in the roof.

A house and barn were also constructed at the site to accommodate the keeper and his family. The list of keepers, from 1799 until the lighthouse became fully automated in 1956, reads like an Island “Who’s Who” list: Skiff, Flanders, Luce, Adams, Pease, Poole, Lambert, Vanderhoop, Bettencourt.

Living at the light meant keepers and their families were blessed with arguably the most scenic vista anywhere on the East Coast. It was not an easy life though. The oil to fuel the light (first sperm oil, then mineral oil, then kerosene) had to be lugged up all those stairs, and the light required constant cleaning. Then there was the water situation – so much to see, but none to drink. Richard Skidmore, who has served as the light’s keeper with his wife, Joan LeLacheur, for the past twenty-one years, says, “The real problem here was there was no water on the property.” Keepers and their families had to travel to a spring a mile away to fetch potable water.

The problem of obtaining supplies led one nineteenth-century keeper to demand that a road be built to facilitate running the lighthouse, and thus began the construction of State Road, which ends just before the lighthouse grounds. It was the first engineered road in town.

The Gay Head Light was considered so important to navigation – Richard likens nineteenth-century Vineyard Sound to Interstate 95 – that it was decided to replace the old light with a lens light. The award-winning Fresnel lens was brought over from Paris and a new lighthouse was built, a brick structure sturdy enough to house the new lens with its 1,008 prisms. (Despite the investment in the Fresnel lens, the area just offshore remained dangerous and was the site of the Vineyard’s worst maritime disaster, the shipwreck of the steamer City of Columbus on January 18, 1884, when about a hundred people died.)

The lighthouse and its fancy lens, along with the grandeur of the clay cliffs, drew tourists. “Famous Gay Head!” read an 1886 advertisement for the steamboat that took tourists from Oak Bluffs to Aquinnah. “The sail is one of the loveliest along the American Coast, on the one side skirting the shores of the Vineyard, with its beautiful scenery; on the other the noted Islands Naushon and Pasque, where the New York Club Houses are located; Vineyard Sound, the great Metropolis for thousands of vessels, often time one hundred or more are seen on these trips.”

The residents of Aquinnah, at that time entirely a Wampanoag town, welcomed these tourists. Businesses sprang up, including restaurants, inns, and shops. To this day, tourists can enjoy Wampanoag cuisine and wares at the Aquinnah shops, which share the top of the cliffs with the lighthouse.

Tourists can also enjoy the light, though the Fresnel lens was replaced in 1952 with an automated electric beacon. This summer the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, which manages the property for the Coast Guard, expanded the weekend sunset tour tradition started in 1990 by Richard and Joan, and it is open Tuesday through Saturday 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Friday and Saturday for sunset. The historic Fresnel lens now resides at the museum grounds in Edgartown, where it can be viewed by visitors.

– Rachel Orr

West Chop Light

The shimmer of sunset’s fading light over Vineyard Sound. Stars shining above nearby islands. The softly glowing lights of seaside homes. These fickle glimmers were once all that ushered boats into bustling Holmes Hole harbor, now known as Vineyard Haven harbor.

Although West Chop residents fervently appealed to their congressman for years to build a lighthouse, their vision wasn’t realized until 1817. Four acres of land were purchased for $225 with funds appropriated by Congress, and soon after, a stone lighthouse tower marked the entrance to an important safe haven and the Island’s busiest harbor.

Captain James Shaw West was the first lighthouse keeper and lived in a tiny stone house adjacent to the tower with his wife and eleven children. For almost a century, the lighthouse had only three keepers, but underwent many construction projects. By the mid-1800s, crumbling buildings and erosion inspired the acquisition of a new building site near the original property, which welcomed a new lantern, keeper’s quarters, and tower. A fog signal was added in 1882, and so was an assistant keeper who would require housing. A wooden frame house was built for him and within a few years, it was matched with an almost identical new keeper’s house.

By 1891, the light tower was in such disrepair that the current forty-five-foot-high brick tower was built to replace it. Shortly after, it was painted white and has remained so since.

In the past hundred years, the property has seen just one major change: In 1976 the Island’s last manned lighthouse was automated. The daughter of one of its last keepers, Seamond Ponsart, who resides in Louisiana now, lived at West Chop Light during the forties and fifties. To say the least, she enjoyed growing up at the light. She fondly remembers the solitude for her family in winter and playing a lighthouse-tower version of Rapunzel. When she was a bit older, she gave a private tour of the lighthouse to President John F. Kennedy and his family.

She recalls just one shipwreck, involving a man and his eight-year-old son; their tiny bass boat capsized and sank during a nor’easter. “We brought them to our house, dried them out, fed them, and had them stay about four to five days,” she says.

The U.S. Coast Guard’s Aids to Navigation Unit in Woods Hole is now responsible for the lighthouse, and Island-based Coast Guard employees – Chief Jason Olsen, the officer in charge of Menemsha, and Food Service Specialist Joe Walker – occupy the two dwellings. Both of their families agree the shared waterfront property makes an idyllic setting for raising a family. On Easter they hosted a big egg hunt, and their children enjoy playing games like manhunt and horseshoes together. The two men are happy to help out by mowing the lawn or resetting the automated foghorn, but are quick to contact the Woods Hole unit if they detect any problems.

Chief Olsen says it was easy to adjust to the steady stream of visitors and sound of the Island’s only foghorn. “It was designed to project sound away from the property,” so it doesn’t even wake his newborn son. He imagines that “leaving will be the hardest part [of living here].”

Instead of directing whaling and merchant ships, West Chop Light now guides ferries, yachts, and fishing boats in what is still one of the state’s busiest waterways. The original lens casts a white light every four seconds, though one window pane is red to alert boaters near the shallow areas of Squash Meadow and Norton Shoal. The distinct light patterns of West Chop Light and other lighthouses can help sailors identify their locations when GPS fails.

While it’s likely that its lens will one day be swapped for LED lighting, the Coast Guard’s Senior Chief Jeffrey Rivett, who oversees the property, believes West Chop Light will continue serving as a critical navigational beacon, Coast Guard residence, and beloved Island landmark well into the future.

Although the lighthouse grounds are private, visitors are invited to park nearby and look out over the expansive views of the outer harbor and Nantucket Sound. Gazing around, they might feel as if they’ve stepped into a painting or history book, perhaps even a fairy tale.

- Moira C. Silva

East Chop Light

It was a lighthouse the government didn’t want to build, remarkably enough.

There are two headlands at the entrance to Vineyard Haven harbor – West Chop and East Chop – and a lighthouse had stood at West Chop since 1817. This made perfect sense, since the waterway sweeping past both points of land was among the swiftest, most shoal, and most dangerous along the whole of the eastern seaboard.

As a coastal highway for a growing nation, it was also among the busiest and most important in the world. At East Chop in 1801, an entrepreneur had built the first in a parade of fourteen hilltop semaphore towers between the Island and Boston to signal city investors that merchant ships from around the world had arrived safely at Vineyard Haven (then Holmes Hole), from which they would then sail on to their final destinations of New York or Boston. Yet when Silas Daggett, a mariner from Holmes Hole, petitioned federal officials in 1869 to build a light at East Chop to further define the entrance to this vitally important little harbor, he could tell by the end of the meeting that the feds thought the West Chop Light was sufficient.

So Captain Daggett himself raised the money from maritime interests and insurance companies and built a wooden lighthouse and dwelling on old pasture land at East Chop. In 1871, just two years after it was finished, the lighthouse burned, so Daggett raised more money and built it again. He served as its keeper until 1875, the year Washington finally agreed that Daggett had had a point about the importance of the harbor and the perils surrounding it, and bought the light and property from him for $3,500. In 1878 it built the cast-iron tower we know today.

The most famous keeper was George W. Purdy, its last. A Newfoundlander by birth, Purdy had lost an arm up to the shoulder when, as an oiler, he fell into the engine of a ship that tended lighthouses and channel markers. (Astonishingly he was able to return to his duties aboard the same vessel just eighteen days after his accident.)

From 1902 to 1933, when automation forced his retirement, Purdy kept the light in perfect order, maintaining and running the motor that turned the lens, sandblasting and painting the lighthouse all on his own – further handicapping himself when he lost an eye to flying paint chips. He even disassembled a steel gantry, from which storm flags were flown, moved it up the hill from Eastville, and rebuilt it next to the lighthouse, again by himself. You can see the concrete foundations for this tower in the southwest corner of the lot, one dated either 1905 or 1908 – it’s hard to tell more than a century later. On this tough and windy old promontory, Purdy is also said to have grown one of the most splendid rose gardens ever seen on the Island.

Painted brown in the 1880s, the lighthouse – which flashes green for three seconds every six seconds – was returned to its original white in 1988 after inspectors found it was heating up too much, causing condensation and rust. Along with those at Gay Head and Edgartown, the East Chop Light is now managed by the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. The last lighthouse built on the Island, and the only one to be privately financed and independently built, the East Chop Light is open for sunset tours on Sundays through the fall; parking on residential East Chop Drive is limited.

Edgartown Light

In May of this year, six months after my solitary move to Martha’s Vineyard, I trekked out to the Edgartown Lighthouse for the first time. It was the beginning of a moody and monotonous weather trend that defined the days of May. That particular afternoon, the air was so thick and wet you felt as if you could scoop it with your hands, and the stickiness coated your skin like candy. At the top of the trail that leads down from North Water Street to the lighthouse, I was joined by a young mother, her newborn daughter, and their dog. They turned back halfway down the path when the wind, which had begun as a nippy breeze, evolved into a bone-chilling force. Once I could see the shore, I made out the shapes of two fishermen in yellow waders and jackets, dwarfed by the wall of hissing spray. I could see two small dogs running at their feet and barking, but any noise was deafened by the roaring sea.

For a lighthouse, dramatic scenes like this come with the territory. In the case of the Edgartown Lighthouse, it’s a job for a solitary forty-five-foot-high white cast-iron tower with a black lantern atop flashing red every six seconds. The lighthouse serves as a giant whipping post for the sea. What this lone defiant structure endures night and day is a testament to survival, determination, fortitude – that it not only endlessly endures its hard life with its back straight and its head high, but that it continues to do so while shining.

The first Edgartown Lighthouse was built in 1828 on a small, man-made island near the entrance of the harbor. The lighthouse keeper had to row out more than a thousand feet to get to the structure, which sat atop wood pilings. Two years later, a long wooden boardwalk was built out to the house. Like a lover’s lane to nowhere, they called it the “The Bridge of Sighs,” as couples drew out their goodbyes on the walk to the lighthouse before being separated for weeks, months, or forever by whaling voyages. When you’re out there on a misty day, all that longing still lingers heavily in the air.

Adding to the sorrow that hovers around the light is its tender memorial to children who have died, dedicated in 2001. The inscription, taken from a poem by Tomas Napoleon and surrounded by thousands of cobblestones engraved with the names of those children, reads: “Let the celebration of all our children and their endless youth, when the world was to them still without problem, Always be that unforgotten Vineyard summer – An everlasting day.” It is the harbor’s way of always leaving a light on, when humans can no longer.

A fellow wash-ashore, the current Edgartown Lighthouse was dismantled and transported here on a barge in 1939 from Crane’s Beach in Ipswich after being relieved of her post there. She was a replacement for the original Edgartown Lighthouse, which was severely damaged in the 1938 hurricane. Moving to Martha’s Vineyard was a second chance for her as well. On my May visit, I felt I had received an answer to the tireless “Why did you move to an island?” question. I like to think that, like so many lost ships, the lighthouse signaled me to safety.

Over the years, sand gradually filled in the area between shore and where the lighthouse stands today. Now converted to solar power, the lighthouse, under the auspices of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, is open daily from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Fridays until 8 p.m., weather permitting.

Cape Pogue Light

No wonder there’s a lighthouse out at Cape Pogue, the gracefully curved northern tip of Chappaquiddick. Long before the Cape Cod Canal was conceived, the waters surrounding the Cape, Nantucket, and the Vineyard formed a maritime superhighway in want of traffic signals. One hardly had to be a navigation expert to spot Cape Pogue on a map and declare, “By golly, let’s put a signal right there.” Hence Cape Pogue Light was built in 1801, becoming the second lighthouse, after Gay Head, to be commissioned on the Vineyard. (Incidentally, Pogue rhymes with rogue. Whether the spelling should be “Pogue” or “Poge” is a debate worthy of another entire article.)

Cape Pogue Light is not your typical in-town, easy-to-find, easy-to-reach landmark. You won’t discover Cape Pogue Light on a mere bike ride or bus tour. It has an uncommon mystique among Vineyard lighthouses, and to know it, you must first venture over to Chappaquiddick.

Your journey begins in earnest at the far side of Chappy’s Dike Bridge. Hang a left and head north over the narrow barrier dunes that separate Cape Pogue Bay from Muskeget Channel and the ocean beyond. Avoid the nesting season. Rule out high tide. Let some air out of the tires of your four-wheel drive. Yes, four-wheel drive. Don’t even think about plying the sands with that rent-a-Jeep with the automatic gearshift.

Better yet, book an excursion to the light with the Trustees of Reservations, the stewards of Cape Pogue Wildlife Refuge as well as the lighthouse itself. The Trustees have rugged, sand-ready trucks. Your trek won’t be a thrill ride however. It’ll be a ten-mile-an-hour slog over three-and-a-half miles of deep, undulating tire grooves. So what. Maybe you’ll glimpse the deer herd or the old sheep-shearing pen. And you’ll have the luxury of time to learn about Cape Pogue Light, perhaps from Paul Schultz. Paul has been lovingly tending Trustees properties on Chappy for twenty years. He’s got facts and lore galore.

“The lighthouse has been rebuilt three times since 1801 – in 1838, 1844, and 1893,” he recounts on a bouncing drive up the beach. “It’s been moved seven times because of erosion. The last time it was moved by helicopter, in 1986.” Apparently, the tip of Chappy is as delicate as it looks.

You’ll be absorbed in the story, the sights, the sea breeze, and all, and suddenly you’ll reach the grail. The lighthouse of mystique turns out to be a little charmer, clad in gleaming white shingles and black shutters and punctuated by a red door. The tower was intended to be temporary when it was built in 1893, yet it still stands strong. The interior is graced with a handsome, curving staircase salvaged from its 1844 predecessor. The Fresnel lens in the tower is at once a work of art and an engineering sleight-of-hand, beaming light nine miles out from a bulb the size of a large grape. Solar panels keep the light blinking white every six seconds. The Coast Guard checks its operation but once a year.

Some fifty thousand people from all over the world visit the lighthouse every year, according to Paul, whether on guided tours or on their own. The most frequently asked question by the younger set is: “Where does the lighthouse keeper sleep?”

There is neither a house nor a keeper at Cape Pogue Light. Once upon a time however, President Thomas Jefferson appointed Matthew Mayhew the first keeper. Mayhew lit the whale oil lamp in the tower in December of 1801 and settled into a new keeper’s house. He and his wife would raise eight children in a harsh environment that’s considered remote by today’s standards, to say nothing of yesteryear. After Mayhew died on duty in 1834, his replacement was unable to arrive to tend the light for two weeks due to ice. In the interim, a schooner wrecked off Cape Pogue, and several passengers froze to death. The last keeper stepped down in 1943 when the light was automated. Ten years later, the keeper’s house was torn down.

The closest thing to a keeper’s house at Cape Pogue today is a smattering of latter-day summer homes just north of the tower. The closest thing to a keeper is the wide-eyed young visitor who imagines how life there might have been.

The Trustees runs three tours daily (9 a.m., noon, and 2:30 p.m.) out to the lighthouse, which is the only way to see inside the building, and there’s no ignoring the view from the top. At sixty feet above sea level, it sweeps from Wasque to Oak Bluffs and across Nantucket Sound to Cape Cod and out toward the Atlantic Ocean. And it’s true what they say: On a clear day, you can see Nantucket.

– Shelley Christiansen

The Lost Lighthouse

The beacons on West Chop and East Chop weren’t the only luminary guides for seafarers coming in and out of Vineyard Haven harbor in the nineteenth century. Built in 1854 to supplement its neighbor on West Chop, the Vineyard Haven Harbor Light once sat atop the bluff along Lagoon Pond Road where the old Marine Hospital stands today.

The lighthouse was just a two-story house with a lantern tower, but its light dutifully guided boats for about twenty years. The lighthouse was then abandoned for a few years, during which time the government erected the East Chop Lighthouse to replace the privately owned lighthouse that had previously operated there.

Ownership of the Vineyard Haven Harbor Light building was transferred to the Marine Hospital Service in 1879 for use as a medical facility. While the structure was no longer a lighthouse in its own right, in the years to follow a red range light was hung from the hospital’s flagstaff to guide vessels. The Marine Hospital was housed in the old lighthouse for less than two decades before a larger, main building was constructed in 1895. Yet for many years the red range light continued to be hung nightly atop the new building’s flagstaff.

Since the Marine Hospital was disbanded in 1952, the property has changed hands several times and may soon be the new home of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

– Simone McCarthy

In addition to those quoted, sources include the Dukes County Registry of Deeds; Steve Durkee, a volunteer keeper and guide at the East Chop Light; the Martha’s Vineyard Museum; the Trustees of Reservations; the United States Coast Guard; Vineyard Environmental Research Institute writings by William Waterway Marks; the Vineyard Gazette archives; as well as Lighthouses of Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket by Admont G. Clark; Lighthouses of Massachusetts by Bruce Roberts; Moshup’s Footsteps by Helen Manning; and New England Lighthouses: A Virtual Guide by Jeremy D’Entremont.

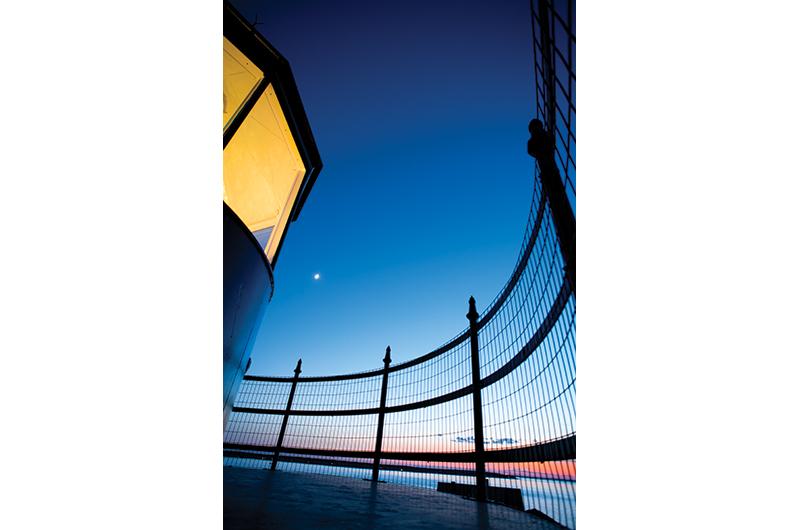

These photographs are from a new body of work on lighthouses at Alison Shaw Gallery, 88 Dukes County Avenue, Oak Bluffs.