On a glorious late summer’s afternoon, the Gay Head Cliffs glow with color on one side; the sea gently laps at the warm sand on the other. Ah, nature!

But on the strip of sand between cliff and sea there is what looks like a trade show for outdoor furnishings: umbrellas, coolers, chairs, tents, tote bags, volleyball nets, entire patio sets. Oh, naturists!

What a dumb euphemism “naturist” is, for the hundreds of naked people on this section of beach are really in no more of a natural state than their togged counterparts a mile or so along the shore.

Indeed, they are probably less so. Less clothing means more umbrellas, sunscreen, and tents; the longer walk from the car means more coolers; the desire to keep private parts grit-free means more chairs. And in many cases, there is not actually less clothing; it is just distributed differently. Lots of hats and quite a few T-shirts.

As for the folks who brought all this stuff, they appear as much a testament to runaway consumption as their belongings. Not many have the lean, hard bodies of people who spend a lot of time exploring the natural environment. A fit few play Frisbee, but hardly anyone ventures into the sea, which is perhaps understandable given the shrinkingly cold water.

And while some of them do actually walk along, checking out the scenery, many seem oblivious of the beauties of nature around them, as they lose themselves in their books, laptops, cell phones, and personal music systems.

It is, to be frank, a little off-putting. Not the nudity, per se, but the banality of the nudity. It’s about as joyous as cruise ship shuffleboard and seems to appeal largely to the same demographic.

There is, I fancy, rather less interaction, less playfulness and laughter here on this beach than on other Vineyard beaches in the summertime.

It seems somehow...inhibited. I imagine that if one simply threw off one’s clothes and gave a yell and charged down the beach to plunge into the sea – which is how I recall my relatively few skinny-dipping exploits – these people would look askance.

My reflections turn political. Maybe, in the age of George Bush and the Moral Majority, Christian fundamentalism and what we might call a new American conformity, nudism has become defensively demure.

When I’ve tried to explain this sense to friends, they’ve accused me of “over-thinking” it. What did I expect? The summer of love?

I didn’t know, so I went to talk to the experts.

Uncovering a culture

A computer search turned up The Naturist Society and a phone number for Nicky Hoffman Lee, co-owner of the society as well as editor of its quarterly magazine. (Both the society and Nicky are based in Wisconsin, which I took as evidence in support of another theory about naturists – that being one appeals more strongly to people who live in cold climates, like Sweden and Wisconsin, who cherish any chance to disrobe.)

The Naturist Society is a group whose efforts to be as inoffensive as possible extend to its name.

“Naturist seemed softer and friendlier than nudist,” says Nicky, going on to contend that a new priggishness has asserted itself over the past decade or so. Nudity has been progressively banned from beaches all over the country. In fact, she says, her organization no longer recommends any place in New England to its members.

She refers me to Bob Morton, executive director of the Naturist Action Committee, the nonprofit, political arm of TNS, who says it is true no beaches in New England are officially recognized as nudist-friendly (the closest such one is in New Jersey).

But he notes Martha’s Vineyard’s tradition of “tolerance and live and let live.”

Nicky directly blamed the Bush administration; Bob does not trace it so directly to the White House, but says there is definitely a new prudishness abroad in America, particularly official America.

“There is no doubt some of the rhetoric is getting a little more stiff,” he says. “There have been hard times in recent years.”

And yet a national poll commissioned by the Naturist Education Foundation, the nonprofit, informational arm of TNS, in 2006 found a substantial majority of people (74 percent) thought there was nothing wrong with nude bathing at designated beaches.

More than half the respondents also thought special places should be set aside for such bathing, and more than one-quarter had participated in nude swimming or sunbathing at some time. The results, Bob says, are evidence of a “disconnect between enforcement and the attitudes of the people.”

The search for the naked truth leads next to Peter Simon, longtime Island nudist and chronicler of nudity, through his photographs and writings.

Peter, who lives in Chilmark, has himself become more restrained about expressing his penchant for nakedness in recent years, in part on the advice of his friend Alan Dershowitz, the noted civil liberties lawyer from Harvard Law School (who can sometimes be spotted on the beach wearing little more than a cell phone in summer).

“Dershowitz calls me: I’m a sexual harassment case waiting to happen. He thinks – people think – my boundaries are not well drawn about when it is appropriate or inappropriate to be naked,” says Peter.

“I still walk around this house or by the pool naked,” he says. “But I’ve learned to be more restrained. You have to be restrained in this country.”

That’s a somewhat sad and belated realization for him, for he has been not just a practitioner, but an avid advocate of the naked way for forty years, ever since his first adolescent experience of it in the summer of 1968 at the beach at Zack’s Cliffs, on what was then part of the Hornblower estate, off Moshup Trail in Aquinnah.

“I first went with a bunch of friends,” he recalls. “We’d heard that there might be nude people.

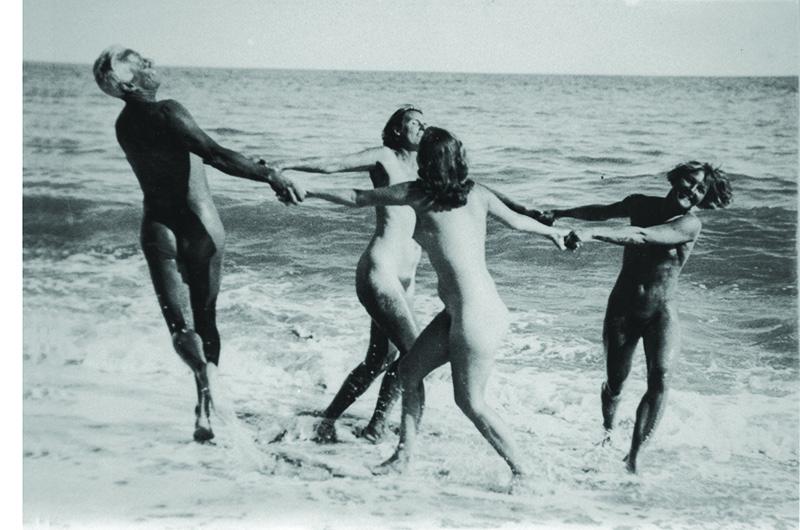

“Then we got there, and it was kind of misty. It didn’t seem like anyone was on the beach, and then the mist blew away and revealed ten or fifteen really beautiful women – it seems to me in my recollection – all just bathing and frolicking in the surf.

“We were college kids at the time, and just thought we’d found nirvana.

“It became a cause. And then a movement,” he says.

The Zack’s Cliffs beach scene wound down after people began to complain and the police began busting nude sunbathers, and the people moved on to Jungle Beach in Chilmark (now part of Lucy Vincent Beach and restricted to town residents and their guests in summer, but still partly clothing-optional).

“It was very naive [in the sixties and seventies]. At the time, we were a new generation of trusting, loving souls, and this was our expression of being free. At that time, it was my cause. I was one of the main, outspoken people for having it legalized,” says Peter.

The legal issues

But it never was legal, although the law has been enforced with varying degrees of flexibility over the years. The files of the Vineyard Gazette are replete with reports of various outbreaks of hostility over nude bathing and more or less sensitive police actions, going back decades.

In 1976, for example, when Edgartown selectmen decided action had to be taken to deal with nude bathing on South Beach, Police Chief Bruce Pratt sought a new town bylaw, so he could avoid the blunt instrument of the state law that made “public lewdness” a felony.

That seemed reasonable to most people, but the following year, when police disguised as bathers made seventeen arrests, opinion was sharply divided. And when, in February 1983, a middle-aged woman was arrested for swimming naked off a deserted Oak Bluffs beach in February, there was public outrage about overzealous policing.

The debates have been most frequent and heated up-Island. In 1991 in Aquinnah, residents at a special town meeting argued emotionally over a proposal to make nude bathers subject to arrest without warrant and to very large fines. The townspeople rejected the proposed measure, although nudists and others were required to desist from the practice of taking “clay baths,” which were damaging the Cliffs.

In 1979, the debate about the Island’s nude beaches even spilled over into the national press when Anatole Broyard, a literary critic for The New York Times and seasonal resident of the Vineyard, wrote a piece for that paper complaining of the “debris” on Vineyard beaches.

More recently – at least since 2006 – the Aquinnah police chief, Randhi Belain, has repeatedly raised with selectmen the problem of “inappropriate behavior” on the beach. There has again been talk about putting a stop to nudism.

Aquinnah selectman Camille Rose, however, sees the problem as being less with overtly lewd behavior than with incidental offenses caused by wandering nudists.

“Families have had problems with the nudists walking down through other areas. And the [Wampanoag] Tribe is not happy with it. The base of the Cliffs is considered sacred land by the Tribe,” she says. “I ordered some signs last year – which we didn’t put up, we are waiting until we have to – and I thought it appropriate to have some demarcation there. The signs would simply say that beyond this point there is nudity, proceed at your own risk. And the other way around, saying this is a family beach.”

She remains concerned, though, about what she describes as “a preponderance of men” and the need to guard against “potential predators.” Police Chief Belain is far more direct. “Let’s just stop it,” he says, noting there have been “incidents over recent years.”

What sort of incidents? He cites reports of men masturbating, women complaining of having been ogled. How many incidents? Fewer than five, he concedes, and just one serious enough to require action. But he fears the prospect of “a rape or something.”

When it is put to him that such things might equally occur on a clothed beach (or anywhere, for that matter – consider the Catholic priesthood and the Congress), he demurs: “I think the nudity just raises it [the possibility] to another level.The Cliffs are a national landmark. I just don’t think there’s any need of nude sunbathing.”

He would like to see nudists removed from the only two remaining beaches that allow it, Aquinnah and Lucy Vincent in Chilmark.

The early days of disrobing

Having heard Chief Belain’s views, one comes to a better understanding of why the mood on the beach seems so defensive. The forces of illiberalism are just waiting for any excuse to close it all down and bring a part of Vineyard history to an end, to win a final victory in a war of cultures.

And I use the term culture war deliberately. For, long before the hippies, nudism began on the Island as a cultural and political statement, as much as a sensual one. Stan Hart, now nearly seventy-nine, was witness to much of it. Not the very beginning, though, which may be traced to 1919 and the founding of the Barn House, a cooperative of intellectuals, lawyers, and artists in Chilmark.

“As far as I’m concerned, my life began up-Island in 1936,” Stan recalls, as we sip tea on the deck of his Chilmark home. He has resided on-Island full-time since 1968 and was a lifelong summer resident before that. The founder and owner of the Red Cat Bookstore in West Tisbury in the sixties and seventies, Stan has been entrenched in the literary and cultural scene. “We used to come up-Island from Oak Bluffs for picnics. I had cousins who owned property along the Wequobsque Cliffs.”

The kids would climb down the cliffs – there were no stairs then – to swim. Stan’s first glimpse of a naked woman, he recalls, was “the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.” But beyond the titillation, he later came to understand the philosophical and political underpinnings of those who engaged in nudism in those days.

“Back in the thirties, two men dominated the intellectual world,” he explains. “One was [Karl] Marx and one was [Sigmund] Freud. People who lived up-Island in the thirties and forties and fiftieswere for the most part bohemian intellectuals from New York City. Or maybe Philadelphia or Washington. But anyway, their mind-set was steeped in Freud and Marx. Freud proclaimed sexual liberation, and Marx, liberation from oppression or authority.

“Both of them in a sense were preaching freedom, and I think in those days taking off your clothes and running in a state of nature on Martha’s Vineyard, where there was nobody to censure you, was extremely exciting to the intellectual community up here,” he says. “It was like – conformity, the hell with it. It was a bourgeois custom that contained the spirit.

“I got the idea that they would go back to Barn House or to Windy Gates [the estate owned by Roger Baldwin, a co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, and his wife Evelyn], or somebody’s home and drink wine and discuss politics or art....They were exciting people.”

He recites some names, a veritable who’s who of liberal thought over several decades. Among the early Barn House crowd, for example, were the famous painter Thomas Hart Benton and writer Max Eastman. Eastman helped found the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. He was a lecturer in philosophy at Columbia University and editor of The Masses, a magazine combining socialist philosophy with the arts. He was also, recalls Stan, “a rascal and a rake. Not only was he always naked, he always had three or four naked women with him all the time. He was a great believer in life. How can you believe in life if you’re all clothed?

“Tom Benton was always around. It was something else. Jimmy Cagney came. It was an interesting crowd, creative people, exciting, interesting people; and it wasn’t diluted by business types. The business types were in Edgartown, or West Chop, where they belonged. This was Eden up here.

“Stanley King had a great house, here on the south shore. He was president of Amherst. Whitney Griswold, the president of Yale, had a house over on Lambert’s Cove; I used to see him in the fifties. Kingman Brewster, who followed him as Yale president, he also used to come up here and take off his clothes. In fact, if you didn’t drop your bathing suit, you were considered a prude.

“The only one of the Windy Gates crowd, of that lot of bright people, who did not drop his bathing suit, I’m told, was Michael Straight, editor of The New Republic” and one of Franklin Roosevelt’s speechwriters.

He goes on naming names: Van Wyck Brooks, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author and literary historian. Famed artist Jackson Pollock. Alfred Eisenstaedt, the celebrated photographer who took the iconic 1945 image of the sailor kissing a nurse on V-J Day in Times Square for Life magazine, and his wife Kathy.

“He never wore a bathing suit, nor did she. I got to know them pretty well,” says Stan.

“Katharine Cornell was also a nudist. I’ve seen a picture of her and Noel Coward here, and they weren’t wearing bathing suits. Thornton Wilder [the playwright, novelist, and triple Pulitzer winner] came here.”

Oh, Stan can drop some names, but he does it to an end, to underline his belief – shared, he says, with those people and the ones who followed during the hippie time in the sixties – that “if you’re a liberal thinker and want your mind to roam and understand things, it’s good to free your body as well.”

Never in all his time spent naked on the beaches, he says, did he see any of the kind of behavior that troubles Chief Belain.

“The truth is, the sense of being naked with other people liberates you from senses of shame or vanity. I think shyness and shame is sexually based. You know, you grow up in a house of secrets and that produces shame.

“To see people who aren’t secret about anything, intellectually or physically” was for him a wonderfully disinhibiting experience.

Stan still enjoys the occasional nude dip, but he’s a little saddened by the nude scene these days, with its mountains of stuff and its apparent lack of liberal intellectual underpinning.

“The crowd I’m talking about didn’t have money; they were academics or artists,” he says. “Now, the investment community of America has discovered Chilmark. By the scores they come up here from New York and the suburbs of New Jersey and Greenwich, Connecticut, and other cities. Probably the worst nightmare of the 1930s crowd has come into being, with this influx of conforming, buttoned-down almost-Republicans.

“I imagine there are a lot of people who go to Gay Head just so they can go home and say, ‘Guess what? We went swimming without our clothes.’ Like an experiment. They aren’t organically belonging to the Island.”

A prohibition on inhibitions

Peter Simon also expresses a sense of disappointment at the way his sixties hippie dream has been corrupted. For a start, many of his old crowd has begun to cover up.

“I think it’s because nobody loves their body enough to do it anymore,” he says. “They don’t want to look at each other, old and farty and white hair and saggy breasts. Whereas I don’t give two hoots. I just love the feeling.”

But beyond that, he says, the beach now has “none of this adventurous, naive spirit upon which the original movement was built.” The trust has been replaced with suspicion, he says. And the sense of community is not so apparent.

“I think it’s happening in all aspects of our society, the suspicion. And it’s filtered down to nudity. You can’t take a lens to a beach now, without people being concerned about pictures being posted on the Internet. Everyone is scared of pedophiles,” Peter says.

“It used to be all very nonchalant. It’s more jaded now. And people were not as burdened by stuff back in the day. There were no cell phones, laptops.”

Nudism used to be about a minimalist philosophy, about shedding other material things along with one’s clothes. Now, says Peter, the naked carry around as much extraneous stuff as the clothed do.

Aquinnah is more affected by the changes in attitude, he says, than Lucy Vincent, which because it is a town beach is open to only a fortunate few. “Lucy Vincent is more discreet. But there are guards everywhere. There’s walkie talkie–toting beach patrols all over the place, so it’s much more regulated and less free.”

Also somewhat saddened is Stephen DiRado, who has spent twenty-one years photographing clothed and unclothed people on Vineyard beaches.

“In 1987, during an extended visit to the Island, I ventured down off the Cliffs [there was no pathway at that time to enter the beach] to find a proprietary community of people clothed and nude,” he recalls. “As always to this day, I was carrying my tripod-mounted, large-format box camera over my shoulder. People, curious, asked questions about my camera; I in turn asked questions about the history of the people who frequent this particular beach. Within minutes, I was introduced to dozens of families, couples, and individuals who expressed great pride and an inviting welcome to their beach.” But since then, and particularly since the late 1990s, people have become more guarded, and the beach crowd has become, on average, older. He sees three reasons: The first is the same thing Stan Hart complains of: the rich-ualization of the Island.

“I have,” he says, “noticed a trend throughout the years of less and less groups of younger adults. But this is an Island-wide problem, thanks to the prohibitive costs of staying on Martha’s Vineyard.” The second is the threat of the voyeurs, the outsiders “who come about walking down the beach with a concealed camera, snapping away.” The third, opposite threat, is the anti-nude forces.

To many nude bathers, to threaten to “take this part of tradition away...means the end of their history, an Island summer ritual. Many have been coming for decades, and tell me if the day comes that the town stops nude sunbathing, they will not return. This is the only time in a year that they can shed clothes, thus shed any identity in order to release stress and rejuvenate,” Stephen says. He would like to see nude bathing “protected by the Island” for its cultural and historical importance. But if he’s thinking that the likes of Chief Randhi Belain might come to see that nudists need to be protected from others at least as much as others need to be protected from the nudists, he’s being very wishful.

It’s all very sad, for as Stephen says, ultimately the only difference between a nude sunbather and one with clothes is that one applies more sunscreen.