In early july 1967, in a little cottage across the street from the cemetery in Vineyard Haven, a still teenaged Janet Messineo and her then-husband Butch Lesko were looking through the latest issue of Time magazine. The cover story was “The Hippies: The Philosophy of a Subculture.” The article described the guidelines of the so-called hippie code: “Do your own thing, wherever you have to do it and whenever you want. Drop out. Leave society as you have known it. Leave it utterly. Blow the mind of every straight person you can reach. Turn them on, if not to drugs, then to beauty, love, honesty, fun.”

Janet: “We were curious, living here on the Island; we’d heard about these people called hippies and we wondered what they were. You’re reading a magazine and it’s describing what you have on your body – bell-bottoms, beads, flowered clothes, really long hair for the times – marijuana, the music. That’s what a hippie is? We looked at each other, ‘Son of a gun, that’s us!’

“I wanted to be a beatnik when I grew up. It was kind of astonishing that I had turned into this hippie. I had never aspired to be a hippie – hadn’t known there was such a thing, but,” she pauses. “LSD came along – I’m sure that’s what it was.”

Janet Messineo is now a fisherwoman and taxidermist living in Vineyard Haven with her husband Tristan Israel, a Tisbury selectman, landscaper, and musician.

Martha’s Vineyard was a hippie paradise. It was removed from “America” – a refuge from the sixties’ political turmoil. The hippie story on Martha’s Vineyard, with few exceptions, is a “washashore” story that began in the late sixties and grew to invasive proportions in the early to mid-seventies. The alternative lifestyle of “turn on, tune in, drop out” that became known as “hippie” was not something the Vineyard youth were so susceptible to; laid back was something they already knew about.

The Island was used to summer visitors, but these hippie folks were so entranced by its charms that many decided to stay. Some of them had grown up summering on the Island, others (like myself) found their way here by chance or word of mouth. The hippie “invasion” was one of the many mass movements onto the Island after the Europeans startled the Wampanoags. The Island’s legacy of hitchhiking and nude bathing (at least up-Island), the beauty here, and a feeling of openness all contributed to a sense of freedom that, in the ease of summer, was irresistible to unattached sixties hippie youth – whether they were dropping out from college, from the 9 to 5, were trustafarians, or just free spirits. The Island seemed welcoming.

Some hippies were more industrious than others, and hippie institutions were born. While most disappeared after the hippie heyday, others endure. The Black Dog Tavern in Vineyard Haven, known the world over for its T-shirt, was a hippie way station.

So, where have all the hippies gone? Well, they’ve (mostly!) grown up. One of the reasons why few from that time are willing now to accept the term hippie is that its meaning depends on a person’s point of view. There was the dirty, panhandling hippie. The peace and love, groovy stoner/acidhead hippie. The levitate the Pentagon, political hippie. The longhaired, rednecked, out to get the hippie chicks pseudo-hippie. The word was a media invention in 1967 that tried to label a new youth culture eruption. It’s a big word. In many cases, people retain aspects of their hippie past but not the label itself.

Crash pads, camping…and partying

Searching for the earliest evidence of hippie on Martha’s Vineyard, preferably indigenous, I found myself hearing, more than once, “Oh, hippies? The first hippie? You have to talk to _____.” The name that would fill that blank is the person whose house was known as the Love Inn. (Not everyone wants to be remembered, in print, for his or her youthful adventures, so the space above will remain blank.) It was somewhere in the town of Tisbury, and began sometime around 1965 – before the term hippie had been birthed. But the sign out front clearly said Love Inn.

It was not really an inn, more a crash pad. In hippie terminology (somewhat borrowed from the beatniks), it meant a place where you didn’t necessarily live, but – without calling ahead – could sleep, as could others. It was communal in spirit. (Another crash pad near the blinker in Oak Bluffs, where Tilton Tents and Party Rentals is now, was called the Casa Blinker.)

At the Love Inn, you could join the ongoing party at any time, and depending on your stamina, stay for days. Many people didn’t know whose house it was, though the owner was right there with them, partying on.

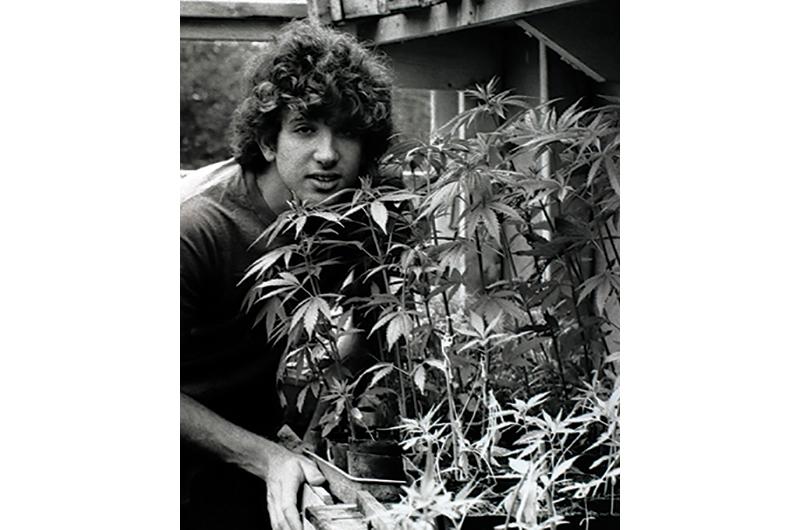

Yes, drugs. Yes, black light. Yes, long hair, ever-present music, and good vibes, as well as good marijuana and psychedelics. Someone who lived there in 1967 says, “We used to have love-ins; we’d put up flyers even off-season. Love-ins would be on the weekends – playing music, making up our faces to glow under the black lights. There was a girl who used to get road kill and skin them. But there were live animals too: raccoons, a boa constrictor in a cage. We were a strange collection of

characters. Some of us didn’t have any place to live and stayed a year or two.”

But don’t make the wrong assumption. It was not a free-love kind of place; it just radiated that love vibe, well before the larger world acknowledged that this kind of thing was going on. As one participant says, “When we were there, we were there, and when we weren’t, no one missed us.” That free attitude encapsulated what was to be the hippie stance.

This was something very new. The Vineyard’s blues maestro of today, Maynard Silva, was in the sixties a teenaged native of Oak Bluffs: “People on the Island thought the Love Inn was just the embodiment of evil. A lot of the Island people, the parents, and the schools were really afraid of the drug angle. But it was weird because, on the other hand, even the oldest, stodgiest Islanders were still pretty rebellious, independent people, so they kind of liked that rebellious hippie quality, and they’d figured out the [Vietnam] war was a crock.”

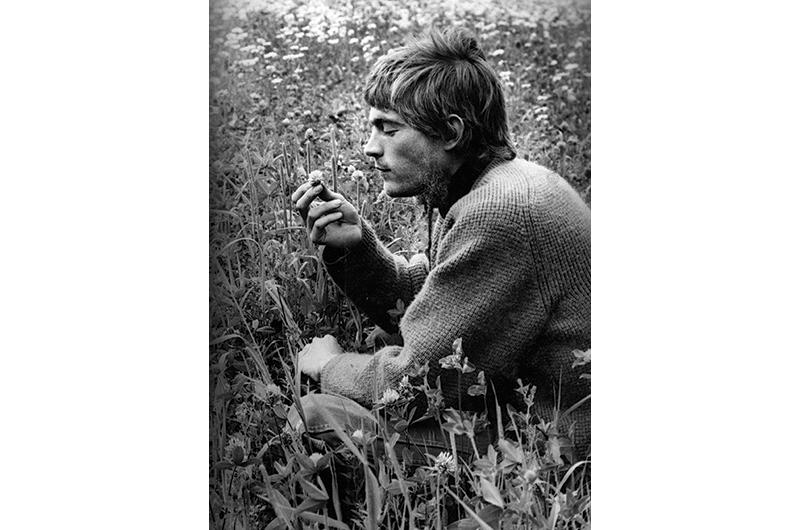

Robbie MacGregor moved to the Island in 1974 from Rockland County, New York, but in the late sixties, he was a summer visitor with an alternative lifestyle. “Living in my VW van, I stayed at Deep Bottom Cove, out at Katama, and in Gay Head at the West Chop Club beach. You could go anywhere along Moshup Trail, pull in any of those little parking lots, and stay for days,” he says. “You didn’t have to have a house, you didn’t have to live somewhere, and you didn’t even have to have a hippie commune. You just were floating around, you were here to be with nature....You’d go where you wanted. Nobody cared – they were glad to see you.”

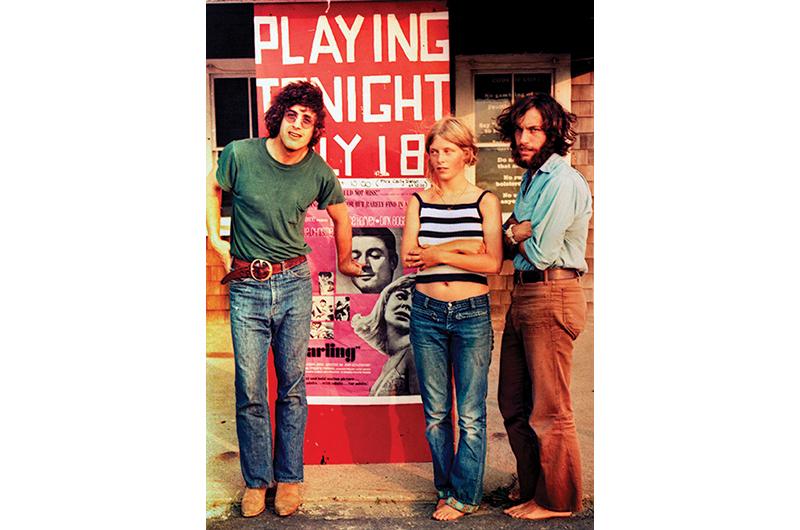

My own Martha’s Vineyard “hippie” tale (although I considered myself a freak, meaning more radical) began on Sunday, August 17, 1969, in the mid-afternoon. With my friend Denny, I was threading through 500,000 people on Max Yasgur’s farmland. Yes, it was Woodstock, the event. It was the hippie nirvana, everyone sharing, eating, drinking, sleeping, making love in the outdoors to a live amplified sound track, in a haze of drugs, goodwill, and sunshine (which had followed the rain). Joe Cocker was singing “With a Little Help from My Friends,” and we were intent on leaving well before the music ended to avoid the certain mega-crush traffic exodus. We were walking side by side toward the road that I expected we would take to hitchhike back down to New York City, where we were living in the East Village.

I said something about how long it might take us to get back, and Denny said, “Oh, we’re not going to New York. You made me come here, so you’re going with me to Martha’s Vineyard.” My response? “Martha’s Vineyard? What’s that?” Thanks to the tragic death of Mary Jo Kopechne in Ted Kennedy’s Oldsmobile exactly one month previous, I had heard of Chappaquiddick, but not the Vineyard. Denny knew of the Vineyard only because a friend of ours, Jim, was shooting a film there. It was still a happy secret of the few.

We disembarked the Islander in Oak Bluffs and inquired how to get to Cranberry Acres, a former campground off Lambert’s Cove Road in Tisbury, where Jim was staying. Walking onto the property in the golden late-afternoon light, we arrived to see – a mini-Woodstock! Instead of Joe Cocker or Jimi Hendrix, a few folks had guitars and hand drums. It was a rustic setting in a wooded area with a pond nearby and dogs, children, Frisbees. Colorful, flowing, tie-dyed fabrics were decorating tents. Marijuana and the buzz of psychedelics were detectable, as of course were long hair, sandals, and the smiles of friends, known and brand new. There were some older and straighter folks (over thirty), but the vibe was easy, loose – all was cool.

Hitchhiking around the Vineyard for the next three weeks led me to Jungle Beach (now Lucy Vincent) in Chilmark in the daytime; at night, running around the Gay Head Light, chasing the beams and shadows as they revolved, or running down the Cliffs on acid under a full moon seemed fine things to do.

Where have all the hippies gone? Well, instead of running around the Gay Head Light, I am now the lighthouse keeper with my wife, Joan LeLacheur, and we live in Aquinnah. We’ve kept the light for the Martha’s Vineyard Museum for eighteen years. While we don’t mind anyone running around the light when we’re there, we do help protect the magnificent face of the Cliffs from climbers, now that they are owned by the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah).

Music, movies…and partying

Music was one of the unifying elements of the youth culture. Maynard Silva: “The best thing out of the whole hippie thing was that for maybe two years, ’68, ’69, they used to have block dances in each of the towns – one was where the restrooms are in the Stop and Shop parking lot in Vineyard Haven, one was at Viera Park in Oak Bluffs, the other was Memorial Wharf in Edgartown. Really good bands would come from off-Island for free. The Commodores with Lionel Ritchie played, right there in the parking lot. One time it was the Velvet Underground. They would play all three towns. The Velvets played the three nights but they didn’t play their song “Heroin,” and then their last night right there on Memorial Wharf in Edgartown, for their last number they played “Heroin” and it was wild!”

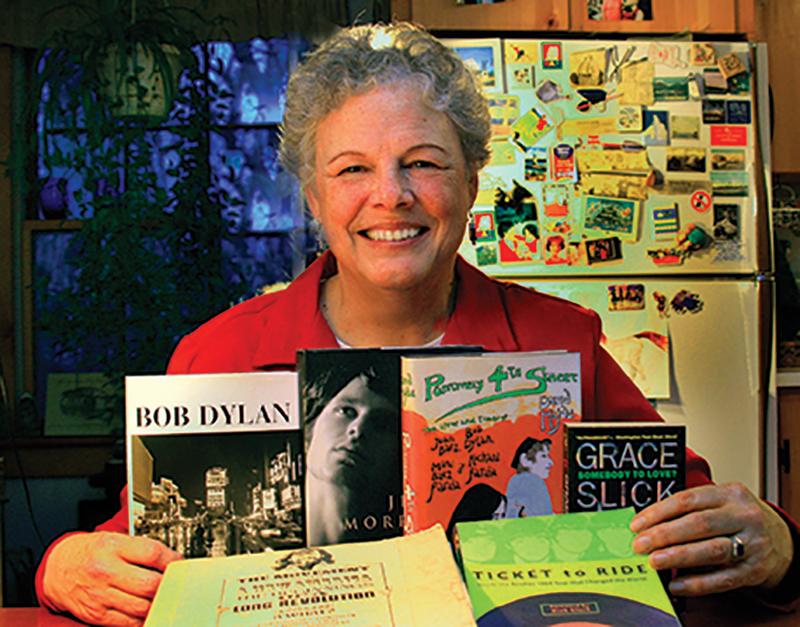

When the influx of young vagabonds became sizeable, the Island’s social services had to adapt. Ann Bassett, a Vineyard native who now sells books online and produces “The Vineyard View” on MVTV, says, “A hot line was created by [Martha’s Vineyard] Community Services to deal with young people in need, including talking them down from bad trips.” This type of proactive institutional response was in glaring contrast to Nantucket’s “no longhairs” policy. In the late sixties, if you tried to get off the ferry there, you were sent right back on the boat to Woods Hole.

Ann Bassett, who lives in West Tisbury now, was also an active participant in the Island’s counterculture. “I considered myself a hippie,” she says. “I not only used the word, I treasured it. In the late sixties, if you saw someone with long hair or somebody in bizarre clothes, you could almost assume you knew what their politics were, the music they listened to, that they were anti-war.”

The Island A Go Go was where Vineyard groups The Ogres and Acme Rock Service played. It was a happening spot. Now it’s a professional building on Beach Road in Vineyard Haven. Ann says, “My boutique there was called Lorelei. I was designing clothes, and it was the best time to be a designer because it was ‘anything goes.’ The boutique was open all day, every day, and the Acme Rock Service would rehearse there and have concerts at night on the weekends. The space was also used for draft counseling for those wanting to avoid going to Vietnam. There were serious things going on there.”

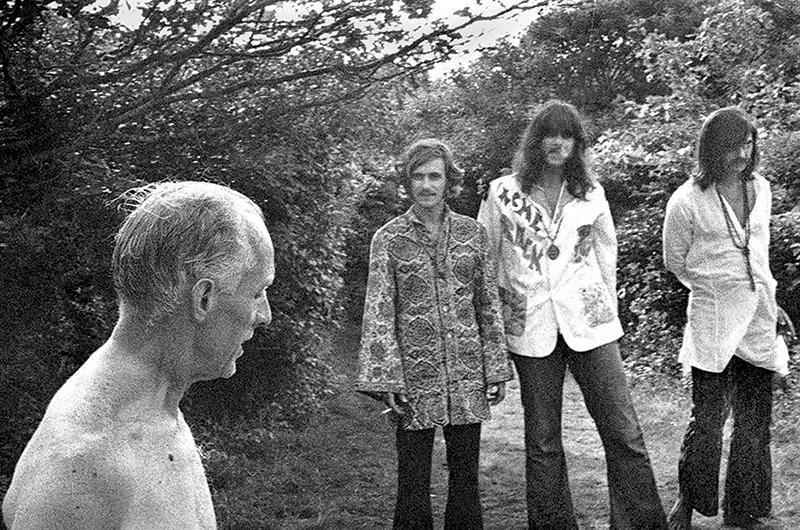

Upstairs in that same building in 1969, photographer (and future author and music producer) Peter Simon, who summered here beginning in the fifties and now lives in Chilmark, was showing underground films in a series called Martha’s Mid-summer Film Festival with his friend Kim Rosen. One night the film to be shown didn’t arrive. Peter and Kim decided to keep the lights low and turn the music up, and they invited everyone in for free. Someone passed around a jug of pink pineapple juice dosed with LSD, and everyone was told it was “electric.” Peter says, “We pulled back all the chairs and put down mattresses. People alternatively danced all night with their best hippie moves, and then crashed on the mattresses and went off into space.” The film audience, happily tripping or stoned, listened to Grateful Dead concert tapes all evening and saw whatever movie their synapses provided.

Peter was happy to be buffeted by the shifting energies of the times and was compelled to document the music, the politics, the zaniness as it unfolded. He says now, “I took photos of it all, because I never wanted to forget it.” I met Peter in 1969 at one of his film screenings, and he was wearing a green paisley collarless jacket and pants, designed and made by Ann Bassett – a trade for shooting publicity photos for Acme Rock Service, the group she managed.

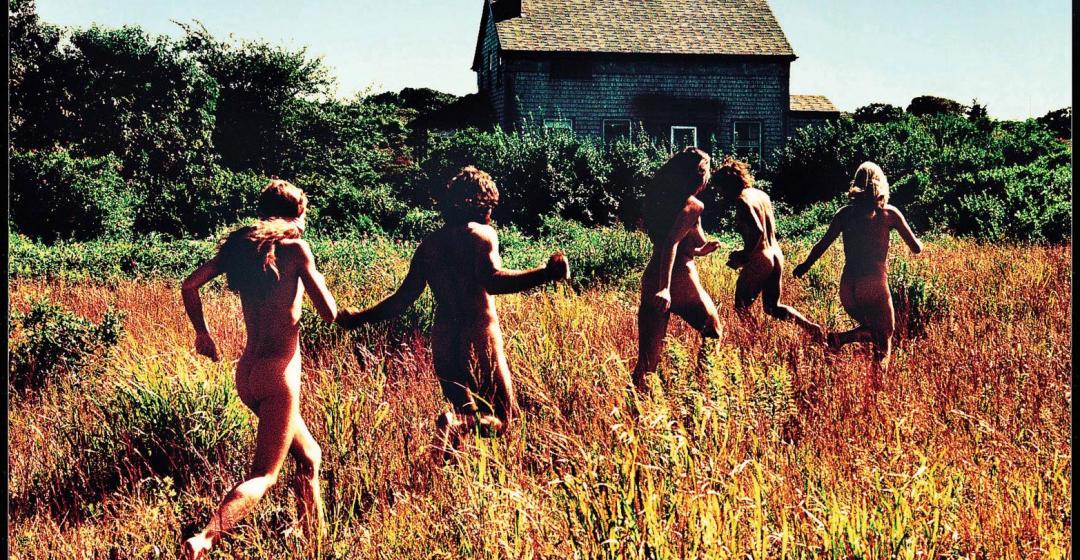

In summer, it was on the up-Island beaches that hippies congregated – often in the nude. A lost pleasure from those times in Gay Head was the “clay bath” made by damming up a flow of water from the Cliffs. Wallowing in the clay and painting it on one’s body felt cool and looked tribal. That practice is prohibited now to preserve the Cliffs.

Peter Simon tells a hippie tale from 1970, when he and a group of maybe fifteen friends, including folk singer Tom Rush, were nude on a beautiful summer’s day on the Hornblower beach (now Caroline Kennedy’s) in Gay Head. Someone had called in a complaint about a group of “nude hippies.” The police chief, the late Kenny Belain, showed up with his “paddy wagon.” Peter says, “He rounded almost all of us up, except a few who escaped into the dunes. But those of us who wanted to do a civil protest surrendered. We were arrested for indecent exposure and got into the four-wheel drive – most of us tripping on acid – peacefully. And as he was driving us off of the beach, the four-wheel drive got stuck in the sand. We all hopped out, some of us naked, and helped push it out of the sand. So there we were, arrested, but helpful, on acid, some of us nude, keeping our boundaries loose in keeping with the hippie ethic. We were off to jail, so I couldn’t get to the movie theater to show that night’s film. Tom, in the jail, couldn’t get a guitar, so he led us all in a round of Joni Mitchell’s “Urge for Going.” A month later, we were in court, fined $25, and told it would be much worse if we were found again on the beach naked.”

Working, artists…and partying

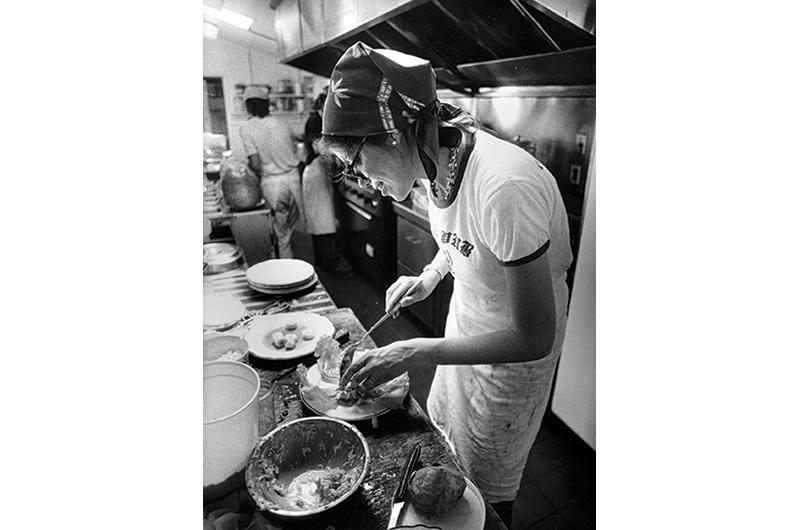

Janet Messineo waitressed at the Black Dog from 1973 until 1976. “Before the Black Dog was built by Alan Miller [at the behest of Captain Robert Douglas, who still owns it along with his family] in 1969, there was no place for young people to hang around – except the bars. Back then, for something to do, we would drop acid, go to the bowling alley, sit at the counter, and have a blueberry muffin,” she says. “After the Black Dog was built, that was a place you could drink coffee and sit around the fireplace. There was homemade bread, real potatoes, just good wholesome food – and lots of it. Alan’s concept was to build a place with a maritime feeling as if it was the nineteenth century, all wood and that huge fireplace.”

Alan Miller, who now owns Pepe’s Cafe in Key West, ran the Black Dog for the first several years, and it catered to harbor folk as well as tourists. Sailors and wharf rats were out on the water as much as possible – off the grid. To them, haircuts and shaving were not necessary. So long hair was no impediment to employment there, and many hippies just off the ferry were able to stay and support themselves by taking a shift at the Black Dog. It was a hippie hangout.

A branch of the hippie aesthetic was reverence for American Indian culture. One craft that was reborn on Martha’s Vineyard in the early seventies was the Native American art of making wampum from the purple and white quahaug shell. It is now a craft that supports perhaps a dozen people here, but it began with Joan LeLacheur, Kate Taylor, and the late Charlie Witham. When Joan and Charlie moved to the Vineyard in 1971, they opened a juice bar on Circuit Avenue in Oak Bluffs, called Nectar. It became a hippie watering hole. Kate, who did not think of herself as being a hippie, feels the term “baby beatnik” is a more accurate description of her young self. She had summered here growing up, and was playing, singing, and recording then, as she does today. Sharing their resources and equipment, the three called their wampum jewelry guild the Black Eagle Mint. Part of their research into Indian lore led to their use of teepees as summer housing.

The police response to the growth in marijuana and psychedelics varied around the Island. A couple of hippie-esque characters from that era separately told their personal versions of the same story: They were in their homes (a tent in one case) off in the woods, with some marijuana on the table in a shoebox top ready for rolling, and a police car comes down the bumpy drive. The police approach the house, walk in without a warrant, take their guns out, put them on the table, and having brought their own papers, begin rolling a joint. While smoking, everyone around the table enjoys some herb tea and light banter, and the cops, waving goodbye, drive off. Not the norm, surely, but it did happen.

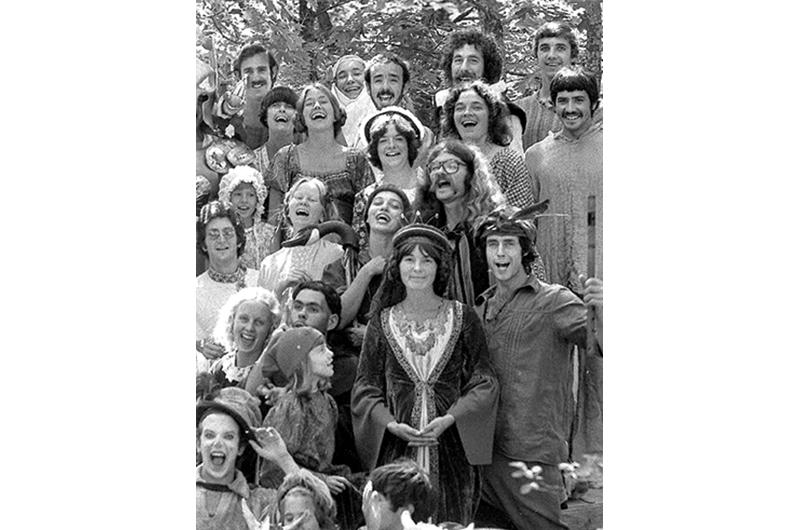

In the winter of 1973–74, an experiment of the late Vineyard hippie era began to form. Anna Edey, now a West Tisbury author and the creator of Solviva (a green design enterprise), is dedicated to sustainable living, an attitude that grew from sixties, hippie roots. She was one of the founders of the Art Workers’ Guild. It became one of the magnets of the mid-seventies arty/hippie crowd – a cultural center for the times. Anna did much of the legwork necessary to turn a large garage on State Road in Vineyard Haven into an artist’s cooperative. She got James Taylor to agree to the idea (he owned the good-sized steel building) and got things straight with the straight world of banks and insurance. “We considered it a community communal project. At that time there was an artistic activist core on the Island, maybe two, three hundred people who were artists in one form or the other, building their houses or doing the seasonal moving.”

Robbie MacGregor, who’s now an artist and builder living in West Tisbury, became involved with the guild as a woodcarving sculptor. “Over the years we kept collecting materials, building studios and lofts,” he says. “A rift developed between the over-thirty’s and the under-thirty’s. The under-thirty’s wanted to have an anarchist commune, basically do whatever they wanted, pretty much – as long as they weren’t creating a ruckus. The over-thirty’s wanted it to be an institution, to have a charter and rules, get a loan from the bank. I was going to the meetings of both sides, and they were both regarding me suspiciously.”

Anna Edey recalls, “We were having one of our incredibly painful meetings; we were split into at least two different camps. It was just an awful meeting. People were absolutely not communicating by anything other than just harsh words and negativity. So I started to roll a joint: the ultimate example of the peace pipe. An example of the good side of pot. There were maybe sixteen of us in the circle, and after smoking, it gave everybody a total understanding of how things could change in a positive way. We were hugging each other, and crying, and completely understanding each other’s point of view. And then the next day...it was back to normal.”

Robbie: “Finally the people over thirty won the struggle, and we all, the under-thirty’s, we all left. It was a political education.” A year later, the over-thirty’s left, and the ideal of an arts cooperative dissolved. But for about five years, it was the scene of art exhibits, art classes, dances, concerts, as well as the site of the Greek restaurant Helios.

Long hair and a willingness to dress expressively made dressing up medieval-style an easy transition for the guild’s artists and others in the hippie arts community. A Renaissance Fair was held in back of the Art Workers’ Guild. Robbie remembers, “There were minstrels and jugglers. There was a stage for people doing medieval dances and songs. There was a guy who had a full suit of armor; he showed up on a horse with a jousting pole! It was pretty amazing and fun. We knew how to have a good time. The whole hippie thing was collectivism. If you did things together, not only was it a lot more fun, but also it was cheaper, and you get a lot more things going on. That was the whole idea. You did things together. Nobody ever thinks like that anymore. The whole reason to come to Martha’s Vineyard now is to get away from everyone. It’s all individuals. I really miss that sense that people were connected to each other creatively.”

When did the hippie era end? As a conscious lifestyle, it faded long ago. People paired off, started families, the Vietnam War ended, many left for elsewhere. Cocaine came along and it was, “Pssst, I’ve got some blow,” and two people would go into a bathroom together instead of passing a joint in a circle of friends. All these factors distracted from the more communal, tribal, hippie ethos. Most people drifted away from their hippie-ness, but for Janet Messineo there was a clean break, “You know when I knew I wasn’t a hippie anymore? When I didn’t want to be associated with the term? I went home one time in 1971, and there was my dad wearing flowered bell-bottoms. That was it.”

The hippie energy of today

All over the Island, you can see people you might associate with hippie culture. Whether it’s their clothes (or lack thereof), their hair, their smell, their attitude. In the sixties and seventies, there was a parallel peace and love movement on the island of Jamaica. Rasta lifestyle and reggae music were something hippies could relate to easily. Along with other remnants of hippie, love of reggae (and dreadlocks) persists here.

Currently, there are two new energy centers on-Island that might be said to carry a strong whiff of hippie. The altruistic sense of sharing and “what goes around comes around” grounds both enterprises. One is the new low-power radio station WVVY FM 93.7. Broadcasting from its studio in Tisbury, it can be heard down-Island, up to Abel’s Hill, and across to Falmouth. A community-based station with an eclectic play list of songs and shows, it’s run by a collective of people volunteering time, energy, money, space, and equipment. WVVY has a free-form-feeling format, and since it just started out December 2, 2007, the crew is still exploring the possibilities. Program Director Bob Lee of West Tisbury describes himself as both “proud to be a hippie and an un-reconstructed bohemian” and says, “WVVY is a voice crying out in our Vineyard-ness. We give and take direction, but there’s a presence, an energy. It’s creating itself. I marvel at the way people have come together on this.” It’s a licensed, above-ground station with an underground sensibility.

The other new/old energy revolves around the Potluck Jams. Island acoustic musicians, most in their twenties and thirties, have come together over an idea that was hatched from a discussion in late 2007 between musicians Willy Mason and Alex Karalekas, who both live in West Tisbury. They agreed that an evening of free food and music was needed to bring folks together. After that chat they drifted apart for a while, and separately each booked a venue and made the idea happen over the winter. Alex used the Grange Hall in West Tisbury, and Willy chose the Chilmark Community Center. Both were successful, drawing a broad cross-section of all ages together in the relaxed spirit felt at hoot-enannies and in coffeehouses of the past. (There have been a handful thus far, but they pop up intermittently, so keep your eye out.)

Musicians play short two- or three-song sets over a nearly five-hour period. It breaks down the formality of the audience-performer relationship and succeeds in creating a living room, laid-back vibe, where dogs thread through the crowd of infants and toddlers, grandparents and teens, twenty-, thirty-, and forty-year-olds – all like some huge extended family. This family, the audience, comes and goes as the musicians come and go on the stage – and all partake of the food.

The group Ballyhoo, which played for free in Menemsha on Sunday evenings throughout last summer on the Texaco dock by Squid Row, is a five-piece acoustic band – one of the largest units at the Potluck Jams. Asked if Ballyhoo has a leader, Brad Tucker of West Tisbury, on guitar and vocals, responds, “Everybody would say that I am, but I’d say there is no leader. We all play a role in it.” Asked about the Potluck Jams he says, “Community dinner and music – there’s a long continuity of that on this Island. We’re happy to be part of it.”

Matt Lozier of Tisbury, the band’s five-string banjo player, sees it this way, “Old-timey, participatory music. Playing for fun. We’re going to play anyway, so we might as well entertain people while we’re doing it.” There is a history here that reaches back to Island living rooms in the 1800s and before, when in-home, family entertainment was the norm. But visually and vibe-wise, the Potluck Jam has a tribal-hippie-2008 style.

As to whether there is a conscious wish to emulate the hippie lifestyle? After talking to some of the participants, the answer is...not really. They’ve got their own thing. Matt says, “I grew up a longhair and very liberal, and my mind-set has always been with the proletariat, the small guy. I would consider myself somewhat of a hippie even by today’s standards.” But many are wary of labels, any labels. Colin Ruel of Chilmark, guitarist, singer, and a regular at the Potluck Jams, has hair that’s longer than short. When asked if he thought of himself as a hippie, Colin says, “I had a VW van for a while, an old one, and I liked it because it held a lot of surfboards. But I had to get rid of it because people were always calling me a hippie.”

Willy Mason: “I don’t think people make a conscious effort to emulate any particular cultural school. It’s just what makes sense – and the fact that a lot of elements of that culture still make sense is a testament to that culture, I guess.”