Ten years have now passed, their lives as a creative couple unfolding into marriage and family, including seven years in Brooklyn, where they honed their artistic skills and built careers. Eventually, though, with their first baby on the way, they migrated last spring back to the Vineyard, where their son, Razmus, was born.

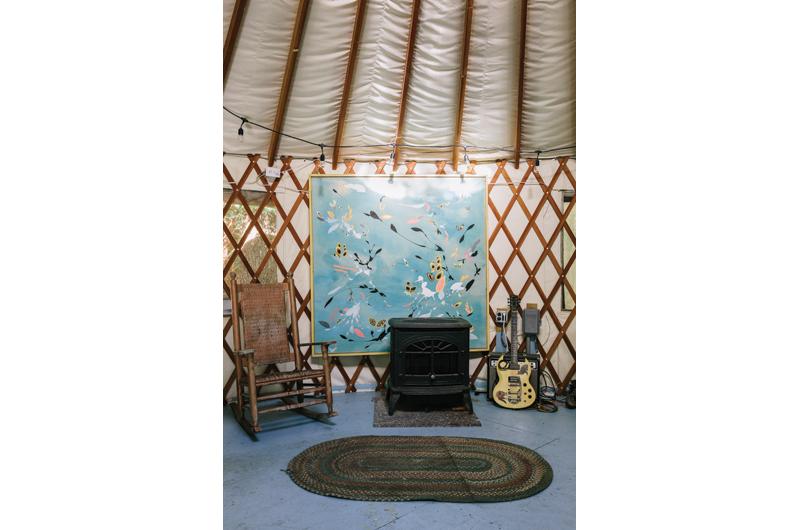

Up a dirt road in West Tisbury, visible through a stand of scrub oaks, their seasonal rental – a yurt – hovered like a bohemian spaceship of creative encounters. (They’ve since moved into a winter rental.) On Ruel’s Instagram feed it’s geo-tagged with a pin dropped on an intentionally map-less, opaque beige background and labeled, “Yurt, Russia.”

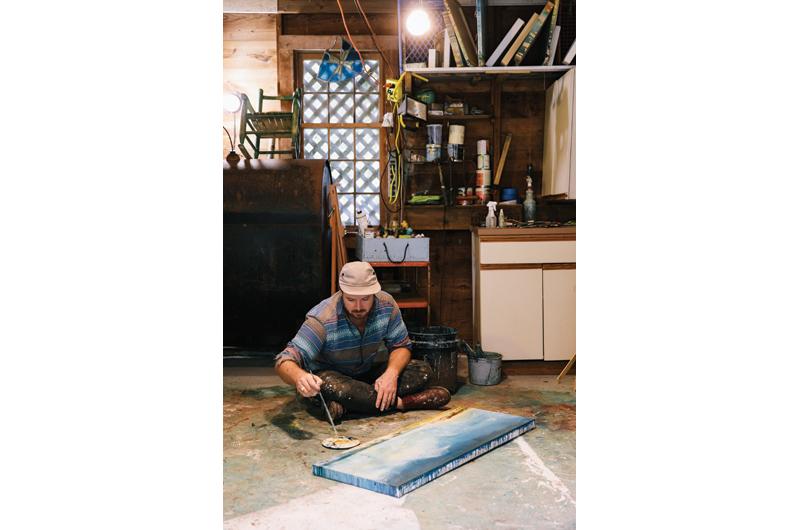

Outside his painting shed, just off the driveway, Ruel stood working on a painting perched face up on a crate. He spoke of early-morning crows chasing late-night owls and lamented failed attempts to protect works in progress from parachuting caterpillars. Twigs and bark floating on the canvas surface were manageable, caterpillars not so much. Inside his studio, an easel stood empty, bookended by finished paintings stacked on edge. Above, more paintings, lying on top of one another like oversized picture books, were piled rafter to roofline. His archives.

Kent, his wife of three years, was in the yurt nursing their infant son. Later she would join Ruel in conversation at the paint-splattered wooden picnic table colonized by his current palette of blues and browns, flickers of red and orange. A painter without formal training, Ruel is well versed in artists’ art and techniques and their lives. He is, one senses, a student of the world, or of the channels holding his attention. He’s all in until he’s not. A free-styling scholar, he spills details and disparate elements, often finishing spoken thoughts with what appears as a dust-up of self-doubt, “I don’t know.” But when the semi-protective particles settle, it’s obvious he knows and he’ll show you.

The song of August’s cicadas swelled in the background as Ruel described the Agnes Martin show at the Guggenheim last fall, when he and Kent were still Brooklyn-based.

“It was just mind-blowing; I think it was one of the best shows I’ve ever seen. Her work is just so peaceful and so obsessive in some ways. I think, what is that she said – I watched the video interview at the end of the show three times – she was talking about ‘keeping above depression.’”

As if on cue, the cicadas downshifted to sotto voce. “I have a tendency to be obsessive. I was obsessive about music. About everything. I just focused and did it and did it,” said Ruel, who previously toured with Vineyard folk musician Willy Mason. “It feels good when I’m making the art and I’m obsessed with that feeling. And unless I’m doing, I’m thinking about it,

because it makes me feel better. It’s hard not to do it, sometimes to the detriment of everything.”

Momentarily distracted by unseen birds in the bramble, Ruel refocused, rotating a weatherworn can of paintbrushes and then moving it from broken shade to a swatch of sunlight. “Sometimes I need to step back and process a little bit. That sort of finds you when it needs to,” he said. “If you don’t take the time, you’ll eventually start making paintings that you don’t feel good about. You get bummed out, then depression gives you time to reflect.”

He possesses a self-awareness short on pretension and long on self-questioning. In conversation, this comes across as thoughtful reflection. “My paintings are the best I can get – the closest – to how it looks in my head. I didn’t go to art school, I dropped out of high school, I don’t always know what I’m doing, but I think that I can tell when something’s bullshit. I realized that it doesn’t matter how something looks; it’s how it feels.”

Ruel’s rule: Keep it real. “I prefer to make mistakes that show some sense of who I am and how I feel about this place,” he said. “If I keep the paintings loose, then there’s feeling in them. It’s a constant battle between trying to achieve what I want to as far as how little detail can I put in this, or how much.” To hear him describe it, this looseness is necessary for transcribing atmosphere, a signature of his work. If it were music, it would be surround sound.

In his current body of landscape paintings one can see, and feel, the influence of his childhood wanderings of the Menemsha headlands. There’s a there there in the almost fantastical terrain anchored by a hyper-focused moment on a single object, like a barn.

In his interpretation of the landscape, the relationship between scale and perspective is intentionally distorted to induce a floaty feeling that makes atmosphere palpable.

As he described his process, Kent, with Razmus nested in her arms, appeared like a Madonna of the woods on the footpath leading from the yurt. Without missing a beat, she took a seat at the picnic table and glided into the conversation. “Whenever I do a new collection, it’s just me working on it. And then when I show it to people I love getting feedback – ‘Oh, that’s what you see?’ – because I’m just in it.” Kent’s method, unlike her husband’s, seems more about unearthing the essence of a design than matching an image in her head. “Colin’s heard me say so many times, ‘I have no idea what this looks like. I have no idea what this is.’ I don’t start with sketching. I have an idea in my head and get into it by carving. Sometimes the idea in the head doesn’t come out in the hands, something different does.”

As Kent spoke, Ruel listened, his gaze softening to the near distance, but his thinking remained almost aloud. He offered tender “yehs,” and when the focus shifted back to him, he responded like a daydreaming student, “Sorry, I was just spacing out.” Not really, though, because then he’d say something entirely on point.

Kent’s conversational style, like her work, is direct and without excess: she distills while Ruel spills. In a way, she’s the anchor to his atmosphere. Their alchemy of communication allows for discussion and opining in an attempt to avoid blind decisions. “Everything we’ve done is intentional, even to the point of having Razmus. We talked about it a lot, for years,” said Kent. “We were scared to have a baby because artists are inherently selfish, and we were scared to give up those twelve-hour days in the studio.” Gazing at Razmus, she said, “I love him so much. It’s crazy. Nothing prepares you. It’s really wild.”

A wave of jays arrived at full volume. “This has been a busy bird morning,” she said, smiling up to the blue jays polka-dotting the tree canopy. Below, on the tabletop, giant black ants wended their way along the weathered wood grain. The day, in their presence, was more articulated.

Kent’s designs – cast from responsibly sourced bronze, silver, and 14K gold – can be described as minimal and inspired by the organic architecture found in nature. She relies on contour, negative space, and texture to capture in metal the elements. The flow of water. Sand beneath bare feet. Wind whispering. Her pieces are carved out of wax and molded, hammered, and burnished to tease out their essence.

This essentialism has resonated with an audience beyond the hem of New York’s fashion world. Women’s Wear Daily, The New York Times, Vogue Latin America, Nylon, Interview,

Huffington Post, and online top-hit destinations like The Zoe Report and Refinery29, to name a bejeweled handful, have featured her work since 2011, some more than once. And most recently, Allure magazine.

Like many creative types, they both sometimes wrestle their intuition. “I’ll work a piece of wax that I know is doomed for too long. I kind of enjoy the challenge,” said Kent. “Do you do that with your paintings?” she asked of Ruel, who answered, “There are paintings I’ll drag through the mud. You make something good – it’s perfect, but then you need to fuck with it. You ruin it, and then you try to fix it, so you work it up to where it’s good again, but you know in your head what it looked like before.”

Kent understood: “I’ve made pieces that didn’t feel right. I made an entire collection, shot a lookbook, and even took it to market. I decided my work needed more color and I did all this beading, but I’m not a beader. My stores said, ‘Nettie, this isn’t you,’ but I already knew.”

On baby-stepping her return to the studio, to finding balance and new streams of intuition in her dual-focused role of a designing mom, she said, “It’s hard, I feel pulled in two directions right now. Biologically, I just want to be a mom. I want to be with Razmus and take care of him, but my identity is so wrapped in my work – that was my baby for so long. It’s still out in the world doing its thing, I just need to feed it.

“I have a strong sense of what I want to do. We both own businesses and we’re both in our heads a lot. We’re forced to define who we are maybe more than other people because

we’re working for ourselves and it’s such a precarious way to make a living.

“It’s so scary, but you have to be all in or there’s no point,” said Kent. Referring to their early years in Brooklyn, “I needed the fear that if I didn’t go to my studio there’d be no work to sell to pay rent.” Ruel added, “We somehow worked by force of will, believing if we worked hard enough it would work out.”

It has. Both their stars are rising on parallel trajectories. During their tenure in Brooklyn, Kent went from working for three jewelers to creating two eponymous collections a year, while Ruel grew from part-time busboy to working as an artist assistant for sculptor Alexander Calder’s grandson Holton Rower and then a full-time painter.

Like other Brooklynites, they dreamed of decamping to upstate New York, where they could afford space without giving up proximity to the city. Realtors still call. Remembering, they spoke excitedly over one another in gentle waves: “But every time we went up there, we were like, ‘There’s no ocean, and I hate mountains,’” and “I felt trapped, like, completely claustrophobic,” and “The sun sets early and casts long shadows,” and then finally, definitively, crossing the bridge back to Brooklyn, “I can’t wait to get home, I fucking hate it up there.”

In the aftermath of the 2016 election and with a baby on the way, the couple decided they wanted to be closer to their family. “The energy on the street was charged,” said Ruel. His wife went on, “I don’t know if it was because I was pregnant, but I felt really vulnerable, that the political climate in New York was threatening. And what I used to complain about this place [the Vineyard] being a bubble, I was actually looking forward to for the protection.” Moving back, though, was a decision Kent had “to evolve in to” because there was fear of losing everything they had worked to achieve.

But if you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere, including Martha’s Vineyard. Ultimately, they answered the call of the Island, where the water feeds their family’s spirit. Life here is easier in different ways. When describing their years in New York, they spoke of desperate searches for swimming holes on Google Maps, lying in trickling creek beds upstate, and surfing crowded Rockaway Beach. “If I don’t go for a swim, I feel super, like, ‘What am I doing with my life? What’s the point of all this,’” said Ruel. And when asked what most about the Island inspires them, Kent answered, “It’s the land. It’s a lot water. I mean, Razmus’s middle name is Ocean.”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)