Whether you’ve heard of him or not, if you’ve been to Edgartown you’ve walked by dozens of his buildings. Since arriving on the Island in 1989, Patrick Ahearn has had a hand in more than 200 projects, 163 to date in Edgartown alone. The work includes preservation, with more than eighteen projects located in the historic districts, adaptive reuse, and new work. A number have been large 7-10,000-square-foot homes, making him an occasional target of criticism by small house advocates, but most of them range in size from 3-6,000 square feet, give or take a finished basement. He’s also designed modest houses, including an 800-square-foot home on Chappaquiddick, and has had a hand in numerous commercial and public properties. Whatever you think of his work, which is usually marked by a profusion of traditional, vernacular, and neo-classical features, his impact on Edgartown is undeniable. Nor does he show signs of slowing down: at age sixty-six he currently has fourteen more projects “on the boards.”

It’s probably no surprise, therefore, that while driving around Edgartown with Ahearn for a windshield tour of his ubiquitous houses and projects, more than a few people casually accost us (well…him) with friendly greetings and effusive accolades. It is clear that his clients love him and – maybe more important – most of the neighbors of his clients like him too.

“It’s Mayberry R.F.D. Americana, a real old-fashioned village,” he says. “The people of Edgartown share a camaraderie. They care about each other and appreciate everything village life has to offer. The harbor, the shops, the walkability…it’s just a nice way to live.”

The approbation from his clients and neighbors comes partly from the fact that Ahearn is reflexively friendly and outgoing. I suspect it also comes from his approach to architecture, which stresses historical context, community, and the needs of the client over the pursuit of a signature style. “I’m the ghost in the night,” he says, “successful when no one sees my hand.”

As thematic to Edgartown as Ahearn’s work may seem to both admirers and critics alike, he is part of a larger movement in architectural history. He’s cut from the same cloth of American regional Modernists who, in the 1960s and ’70s began to move away from the universal theories and austere forms associated with mid-century Modernism, toward a more place-based architecture and planning theory characterized by the return of historical and classical aesthetics.

In general, these architects opted to live and practice in one town or city, attempting to become expert in the local history, culture, and environment. Almost by definition, they are a breed that rarely achieved the celebrity status of internationally known “starchitects.” Chances are good, for instance, that you haven’t heard of Boston’s Jacob Albert, Chicago’s Thomas Beeby, or Anne Fairfax from New York. But by contributing a broad spectrum of building types in a concentrated area, these “neo-traditionalists” and “new-urbanists” have left lasting legacies at the urban/town scale in their respective regions.

In Ahearn’s case, his impact isn’t limited to Edgartown. He began his career in Boston, where he maintains a busy practice and where, over the past forty-three years, he has contributed to more than 1,000 projects, with 400 buildings in the Back Bay alone. His architecture in the city does not emulate the multi-gambrel, shingle-style buildings that characterize his houses on the Vineyard. Rather, this work recalls and reflects Boston’s own diverse architectural history.

“At heart I am an urban designer,” he says. “The buildings I design respond to each unique street and neighborhood. My clients learn that their interests are best served when we collectively consider the interests of the general public.”

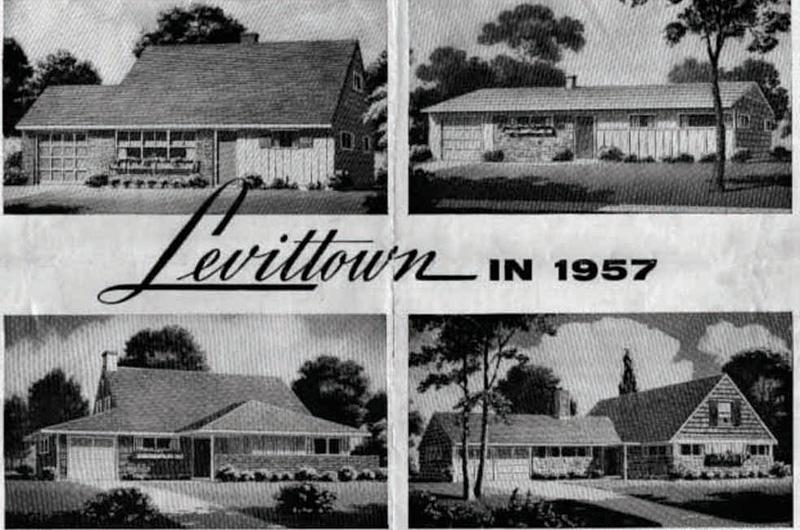

Ahearn’s notions of a collective aesthetic are deep-rooted. In the late 1960s he earned a degree in architecture followed by a master’s degree in urban design from Syracuse University, one of the oldest and most prestigious architecture schools in the country. But his first contact with architecture and planning was Levittown, Long Island, where he grew up. The first postwar mass-produced housing tract, with over 17,000 small homes of only four different designs, Levittown had a tremendous impact on the development of suburbia. Originally conceived to provide affordable houses for returning GIs, it became a thriving working-class community largely due to its master plan that allowed for much open space, while the homogeneous design of the houses conveyed social equanimity. Levittown was, as Ahearn notes, his “childhood foray into planning.”

“I remember making cardboard models of the four tiny Levittown houses and arranging them around my American Flyer train set. The houses were so simple, designed to easily and cheaply expand, which actually happened to many of them over time. Still the neighborhoods always kept their scale and feeling.”

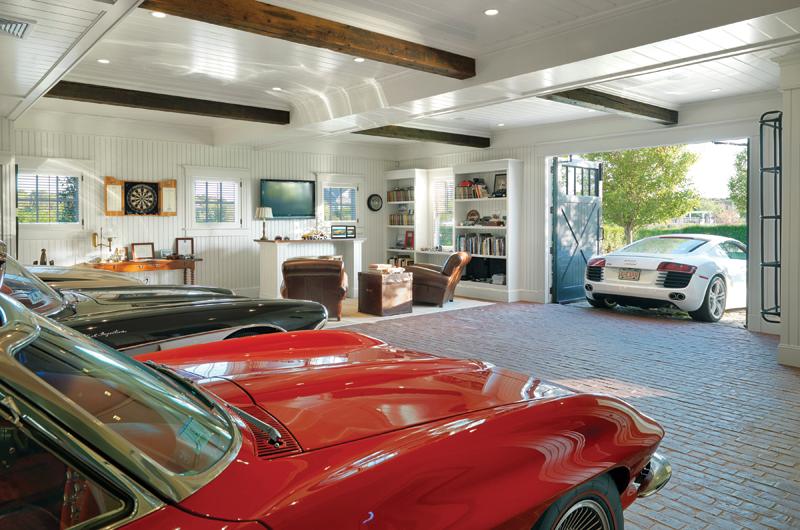

It’s a memory that resonates deeply for him. His children recently gave him a replica of his childhood train set, which he proudly displays in the family “Barn” at the Field Club development in Katama. The Barn is a garage/guest residence that Ahearn designed to be reminiscent of a New England barn on its exterior, while its main purpose is to house his meticulous classic car collection.

In spite of his neo-traditional body of work, Ahearn was first educated as a Modernist. Founded in the classical Beaux Arts tradition, the architecture school at Syracuse was established to educate designers for Manhattan’s growing skyline as well as high-end residences in the city and upstate New York. But whereas some schools, notably Harvard and Columbia, followed the European trajectory of Modernism toward an aesthetic devoid of historic references, the stalwart Modernist at the helm of Syracuse, Kenneth “Doc” Sargent, advocated a strong respect for architectural tradition while embracing Modernism through the use of new materials and technologies. Above all, Sargent’s mandate was to produce competent architects with marketable skills: a professional architect, he liked to say, was more “physician” than “artist.”

“Syracuse taught us first and foremost to be practical and professional as designers, engineers, builders, and craftsmen,” says Ahearn.

During Ahearn’s tenure as a student, Postmodernism emerged. From an architectural perspective, Postmodernism became a new style that embraced historic, classical, and traditional aesthetics. From an urban perspective, Postmodern designers rejected the Modernist response to middle-class (or more accurately, white) flight from urban centers toward suburbs such as Levittown. The Modern “urban renewal” movement involved tearing down blighted neighborhoods wholesale and replacing them with “Brutal” complexes, such as Boston’s City Hall, or massive but often alienating housing projects. The Postmodern “new urbanist” theory Ahearn studied and now practices, on the other hand, encourages designers to celebrate the cultural, environmental, and historic elements that make cities unique, and attempt to design in a way that incorporates, rather than obliterates, existing urban fabric.

Ahearn got his chance to apply this “new urbanism” in his early years working for Benjamin Thompson & Associates (BTA), which he joined in 1975. The Cambridge-based firm was largely responsible for the redesign and rehabilitation of Faneuil Hall, the first adaptive reuse project in Boston, and one that became a model for other cities around the country. During Ahearn’s time at the firm, BTA also lead redesigns of the waterfronts in Baltimore and Miami, as well as the Lodo district in Denver. While at BTA, Ahearn also worked on urban projects in the Middle East, an experience that further solidified his thinking about the importance of understanding and incorporating extant historic and cultural architectural traditions into new designs.

In addition to his day job, Ahearn began to invest in building conversions on his own: the first an apartment-to-condo rehab at 165 Commonwealth Avenue, which he purchased for $145,000 in the swanky but then struggling Back Bay. This initial investment led to many more: the “new urbanism,” it turned out, could not only revitalize city neighborhoods, it could be a very fruitful endeavor.

"I instantly loved the Vineyard,” Ahearn says, thinking back to his first visit in 1989. By then he was married to Marsha Ahearn, who is responsible for the interior design of many of his houses. Together they have five children, who are now grown. His introduction to the Island, however, came about via their Beacon Hill preschool days. Ike Taylor, patriarch of the famous singing dynasty and fellow preschool parent, brought Ahearn on his first Island visit, where he spent time exploring Edgartown real estate.

“The Vineyard harkened back to my summers on Long Island in towns like Greenport or the Hamptons, the perfect combination of rural farmlands and beaches,” he says of his first impressions. “Our family had a place on the Cape for years, but it was not the same. The Vineyard was not as busy or commercial. We liked the lack of traffic and the fact that there were no chain stores. I had small children back then and we really liked Edgartown because the kids could walk all over and bike to the beach.”

Edgartown was not just aesthetically pleasing to Ahearn. As a savvy investor, he saw in it opportunity. With its abundant housing stock ripe for rehabilitation, he believed Edgartown could be very attractive to newly affluent second-home buyers that the boom economy was producing. But only, the urban planner thought, if the village he so admired for its quaintness could become a more upscale or fashionable experience for these new potential buyers.

“When I first came to Edgartown the village was seasonal only, and suffering from benign neglect. It had too many T-shirt and souvenir shops and its storefronts were in disrepair with unsightly additions or bad signage,” he says. “Its balance was in flux. The village had wonderful qualities, like its intimate scale, the harbor, walkability, but it really needed to be coordinated and revitalized.”

Shortly after that first visit, he bought and renovated his first home in Edgartown, right on Main Street, and opened a local office in Nevin Square as an outpost to his Boston practice. Most of his early work was in restoring houses, but he quickly moved on to his campaign to remake the town in ways that he thought would make it more appealing, not only to summer residents but also to the growing population of year-rounders, including new stay-at-home online professionals and boomer retirees. He wanted to see the storefronts cleaned up, more thematically coherent streetscapes, and to amplify unifying features such as the brick sidewalks. His ad hoc outreach culminated in 2005 when he submitted an eighty-page illustrated revitalization primer to the town that suggested both minor and major changes to virtually every single building in the village.

“‘The new urbanism’ that has caught on in the planning and development community is based very much on the concept and scale of Edgartown,” he wrote by way of an explanation of his thinking. “Which is an intimately scaled village, with a vibrant downtown core and a natural or man-made amenity such as the harbor, with a rich combination of historic houses, apartments, shops, and year-round services….” He compared Edgartown’s potential to Faneuil Hall and the Inner Harbor revitalization projects in Baltimore and Miami.

Not surprisingly, not every stakeholder in town aspired to the commercial success of Faneuil Hall, let alone to coherent streetscapes or consistent signage. Edgartown never formally adopted Ahearn’s primer. Several retailers did implement his ideas, however. Also, whether coincidentally or not, the city and various philanthropic organizations stepped up their planting and other beautification efforts in public spaces.

Ahearn himself, meanwhile, turned his attention to one of the buildings featured in the primer: The Navigator Building at the bottom of Main Street, which houses the Atlantic Restaurant on the ground floor. Upstairs is the Boathouse, a private club associated with the Field Club, the Katama development for which Ahearn designed a twenty-six-lot master plan that includes architectural guidelines.

“Before the Navigator there was no outdoor street life at the harbor,” he says. “We set out to animate the streetscape, vital to any vibrant pubic experience. So we opened up buildings to pedestrians, doing some basic things such as using clear glass on display windows, adding sidewalk dining and patios. We added streetlights, planter boxes, street furniture, and opened up the harbor to foot traffic. We used historically accurate details on the building remodel including authentic wood storefronts and iron work, and historic hardware.”

The generations of Edgartonians who grew up dancing at Memorial Wharf or enjoying ice cream strolls under the stars might dispute Ahearn’s assertion that there was no outdoor street life on the harbor, as might the Seafood Shanty. Still, Ahearn’s point is not unfounded: Edgartown nightlife is undeniably busier, and more upscale, than it was thirty years ago. The town might not have adopted his urban primer, but it seems nonetheless to have largely achieved Ahearn’s goals.

Today Patrick Ahearn has three homes on the Island that he has designed for his close-knit family; his five grown children remain regular visitors to the Island. One is the Barn at the Field Club mentioned earlier. At the other end of the Island is a deceptively simple remodel in Aquinnah called “Flip-flop,” a complex made up of two small, restored beach cottages nestled behind tall grassy dunes. The third is his main Island residence on Davis Lane in Edgartown.

While Ahearn’s work is always consciously informed by history, he is not a strict preservationist. Rather, he weaves his particular read on the present into his studied interpretation of the past. Where feasible he will repair and keep historic materials, or go to great pains to recreate materials in-kind. For projects already listed on the National Register, he easily abides by the required conservation standards. But in most cases when he “restores” a historic building or home, his intention is not so much to conserve its original materials as to preserve what he believes is its original nature while not standing out from its surroundings.

And if there is no history to preserve, as is the case in new construction, he happily conjures one up. To help clients appreciate how they, as contemporary owners, fit into the continuum of their particular neighborhoods, he creates detailed fictional narratives that are intended to create metaphoric correlations between the new building and a relevant historic or cultural precedent. He calls the process “scripting.”

“The Edgartown ‘scripts’ revolve around the town’s unique and most prevalent architectural history between the seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries,” he explains. “The grand whaling captain’s house, smaller workers’ cottages, carriage houses, farm houses, and a variety of commercial buildings such as livery stables, barns, boat houses, or other vernacular buildings.”

So, for instance, although his own in-town house is completely new, he began its design journey with a mythical narrative that spans three centuries and incorporates three local vernaculars. “You enter the home through a midshipman’s house built in the 1790s,” he explains. “Not as grand as a captain’s house on the harbor or Main Street, it’s a modest working-man’s home tucked away on a side street. In the 1820s a new owner, a gentleman farmer, took over the house, building a barn directly connected to the original house. Then in the 1890s a livery stable is added at the rear of the lot, fronting a back alley that leads down to the harbor.”

As for his own role in this imaginary history of the house: “I happened on the complex in the early twenty-first century, fell in love with it and took on its ‘restoration’ while adding a number of contemporary amenities including the new landscaped courtyard and pool.”

The historic brick and stone foundations, twelve-over-twelve divided-light windows, and low interior ceiling heights all hearken back to early New England houses. Interiors are finished in many places with reclaimed hardwood and antique hardware, and where contemporary materials are used they have been distressed or “aged” to further convey the period Ahearn is trying to emulate. Much of the exterior trim, on the other hand, is made of Azek and other relatively new composite materials that he employed because they closely replicate the historic wood but are much more easily maintained.

“My buildings have stood the test of time, even if they are only a few years old,” he likes to say. “I’ve toured so many people through this house who have complimented me on the quality and detail of its restoration, and who were shocked to find out that it is completely new. That’s a high compliment to me.”

The script, he believes, allows the design of a building to take on a life of its own, and serves to put the client’s wishes into a larger perspective. With a narrative script, the design process becomes a give and take not so much between the client’s agenda and the architect’s aesthetic, he believes, but between the client and the entire community. Ahearn sees himself as the facilitator between the two.

Critics of large homes might say that while the script produces a historic-looking home, it can provide a handy justification for constructing as much square footage as possible on a given piece of property. The “barn” at Ahern’s home actually accommodates a spacious family room and kitchen, while the “livery stable” houses a garage and guest suite that opens onto the patio and can convert in a moment’s notice into a large event space. Though Ahearn’s own home has roughly 3,800 square feet of living area, not including a spacious basement and garage, he is the first to admit that over the years he has designed some very large houses to accommodate client-driven programs. But he bristles at the notion that large houses cannot exist and be good neighbors on the Island.

“What makes a house too big?” he asks. To him, houses appear oversized not because of any set square footage, but because they are poorly designed. He points to a wide variety of architectural devices he employs specifically to reduce the impact of larger homes on their surrounding neighbors and environment, including breaking up massing with multiple buildings of various sizes, careful siting and landscaping, and fully using available subterranean space.

He notes, however, that he depends on local zoning and building codes to be his architectural ally. He opposed the increase in minimum lot size in Edgartown from 5,000 to 10,000 square feet, which he believes resulted in predictable scale abuses. He also supported the expansion of designated historic districts in the town, because they place restrictions on size, scale, and design based on values that are similar to his own. He has walked away from more than one project where his vision for a property and his client’s desires simply could not align.

To Ahearn, as always, the answer comes down to design, scale, and context. Or rather, what he considers good design at the right scale in any given context. So he unabashedly continues to promote his own brand of neo-traditional design. Because, even if Ahearn’s context is partially or wholly imaginative, it serves, he firmly believes, to keep Edgartown…Edgartown.

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)